Lamar Mounds and Village Site

| |

| Location |

Macon, Georgia, Bibb County, Georgia, |

|---|---|

| Region | Bibb County, Georgia |

| Coordinates | 32°48′43.92″N 83°35′31.85″W / 32.8122000°N 83.5921806°W |

| History | |

| Founded | 1350 CE |

| Abandoned | 1600 CE |

| Periods | Lamar Phase |

| Cultures | South Appalachian Mississippian culture |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1934, 1936, 1938, 1939-1940, 1996 |

| Archaeologists |

James A. Ford, Arthur R. Kelly, Gordon Willey, Jesse D. Jennings, Charles Fairbanks, Mark Williams WPA, Lamar Institute |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | platform mound |

| Architectural details |

Number of temples: 2 |

|

Ocmulgee National Monument | |

| Location | 1207 Emory Hwy., E of Macon, Macon, Georgia |

| Area | 702.1 acres (284.1 ha) |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000099[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

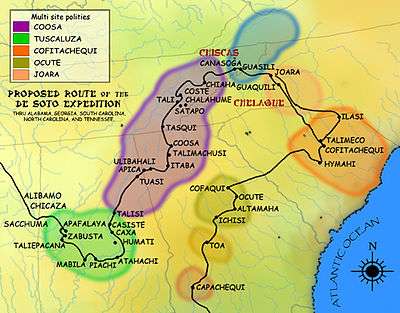

The Lamar Mounds and Village Site (9BI2) is an important archaeological site on the banks of the Ocmulgee River in Bibb County, Georgia (U.S. state) and several miles to the southeast of the Ocmulgee Mound Site. Both mound sites are part of the Ocmulgee National Monument, a national park and historic district created in 1936 and run by the U.S. National Park Service.[2] Historians and archaeologists have theorized that the site is the location of the main village of the Ichisi encountered by the Hernando de Soto expedition in 1539.[3]

Site description

The site has two large platform mounds and an associated village area surrounded by a palisade. The original settlement may have been started on a natural levee of the Ocmulgee River, a location which eventually became Mound A. The main village area spreads out to the southeast from this location.[2] This location may have been island-like at the time of its settlement, the only high ground located in a low swampy area with the Ocmulgee River on one side and an oxbow lake on the other.[3][4] Houses in the village were rectangular wattle and daub structures, some situated on low house mounds, and the 3,500-foot-long (1,070 m) palisade was made of upright logs covered in clay.[5] The palisade encircled an area of about 25 acres (0.1 km2) and followed the island shape of the raised levee. Out side of the palisade was an encirling ditch, probably water filled at the time of the sites occupation.[4] Mound A is a large mound with a round 10 metres (33 ft) in diameter and 10–15-centimetre (3.9–5.9 in) deep depression located in the northwestern quadrant of its summit. This feature is thought to be the remnants of a collapsed earth lodge with a dugout floor and embanked walls. Unlike other Middle Mississippian culture mounds to the northwest, Lamar-style mounds are more rounded in shape as compared to squared-off rectangles.

Mound B, completely round in shape, has a feature almost unique in southeastern archaeology in that it has a spiral ramp leading to its summit. This and other evidence has led archaeologists to speculate that the mound was in the process of being enlarged and given a new layer of fill when work was abruptly stopped. Unlike other Mississippian sites, no evidence of a meticulously clean plaza has been found at the site, although the large area between mounds was once theorized to be one.[2] Two large pits were made at the site, one inside the palisade and the other outside its perimeter. These were probably borrow pits leftover from mound construction. It is possible the inhabitants used the pits as clean water reservoirs and fish ponds, a use described by the De Soto chroniclers when passing through the area.[4]

Lamar culture

The Lamar site was inhabited from about 1350 to 1600 CE, during the late prehistoric and early historic period of the area. The style of Mississippian culture pottery found at the site has been used to define this period in the regional chronology, making it the type site for the Lamar Phase (also known variously as the Lamar culture and Lamar period).[2]

Excavations

In 1936 the site was acquired by the United States government and incorporated into the new Ocmulgee National Monument. It was then extensively excavated during the late 1930s as part of the government’s Depression era Works Progress Administration archaeology program. The site saw a series of major archaeological excavations starting with one by James A. Ford in 1934, Arthur R. Kelly in 1936, Gordon Willey in 1938, and in 1939-1940 by Jesse Jennings and Charles Fairbanks. To protect the site from the flooding Ocmulgee River a large levee was constructed around it in 1941. In 1996 archaeologist Mark Williams from the University of Georgia and the Lamar Institute did test excavations and site mapping, the first archaeological explorations at the site since 1940.[2]

Possible location of Ichisi

On March 29, 1539, the Hernando de Soto entrada, while winding its way northward after leaving Florida, came upon the province of Ichisi, which may have been part of the larger paramount chiefdom of Ocute. They were greeted, at the first village, by women dressed in white mantles with gifts of corn cakes and wild onions. On March 30 they were ferried across the Ocmulgee River in dugout canoes and met by the paramount chief of the province, a man with only one good eye. They spent several days at the village as the guest of the one-eyed ruler. The chief gave de Soto gifts of food and offered him porters and translators to speed him on to the next chiefdom to the northeast, Ocute, a people who spoke a different language from the Ichisi. Before leaving on April 1, the Spaniards erected a large wooden cross atop one of the village mounds and tried to explain its significance to the villagers. Noted historian and de Soto researcher Charles M. Hudson theorized in the 1980s and 90s, that the de Soto entrada crossed the Ocmulgee River near Macon and that the Lamar Mounds may have been the location of the paramount town of the Ichisi,[3] a view supported by archaeologists who have worked at the site.[2][6] New archaeological work at a site in rural Telfair County, Georgia near the town of McRae in 2009 called this identification into question and suggested the crossing took place approximately 90 miles (140 km) further south. Archaeologists and historians are still debating which of the two sites was actually visited by de Soto and his men.[7]

See also

- Coosa chiefdom

- Etowah Indian Mounds

- List of Mississippian sites

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

References

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places". Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Williams, Mark (1999). "Lamar Revisited : 1996 Test Excavations at the Lamar Site" (PDF). Lamar Institute, University of Georgia.

- 1 2 3 Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. pp. 157–162.

- 1 2 3 Fairbanks, Charles H. (1941). "Palisaded town". The Regional Review. National Park Service. VI (5 and 6).

- ↑ "NPS Historical Handbook : Ocmulgee". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- ↑ Williams, Mark (1994). "Growth and Decline of the Oconee Province". In Charles, Hudson; Chaves, Tesser Carmen. The Forgotten Centuries - Indians and Europeans in the American South 1521 to 1704. University of Georgia Press. pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Bynum, Russ. "Researcher: Georgia artifacts may point to de Soto's trail". ABC News. Retrieved 2012-04-15.