Ocute

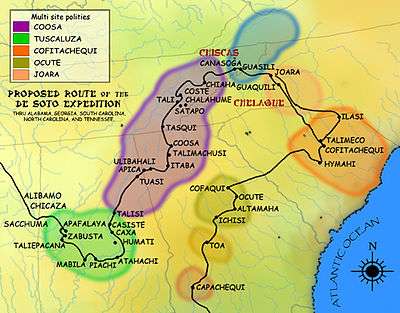

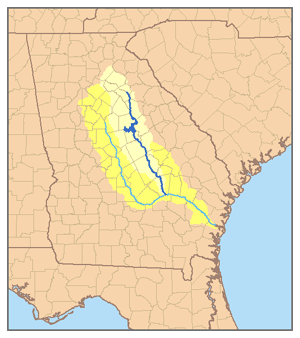

Ocute, later known as Altamaha or La Tama and sometimes known conventionally as the Oconee province, was a Native American paramount chiefdom in the Piedmont region of the U.S. state of Georgia in the 16th and 17th centuries. Centered in the Oconee River valley, the main chiefdom of Ocute held sway over the nearby chiefdoms of Altamaha, Cofaqui, and possibly others.

The Oconee valley area was populated for thousands of years, and the core chiefdoms of Ocute emerged following the emergence of the Mississippian culture around 1100. Ocute was invaded by the expedition of the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto in 1539. At that time, Ocute was locked into a longstanding war with the rival paramount chiefdom of Cofitachequi in South Carolina. The chiefdom remained a significant regional power into the 17th century, although Altamaha eclipsed Ocute as the primary center, leading the Spanish to refer to the paramountcy as La Tama. In the 1660s the chiefdom fragmented due to slave raids by the English-allied Westo, though several of its towns relocated to Spanish Florida and formed part of the Yamasee confederacy.

Description and location

Ocute was a sizable paramount chiefdom, a political organization in which multiple chiefdoms are subsumed under one political order.[1] The core area comprised three chiefdoms located in the Oconee River valley in the Georgia Piedmont: Ocute, Altamaha, and Cofaqui. Each included a main town and mounds along with various associated settlements, with the chief of Ocute being paramount.[2][3][4] Charles M. Hudson and his colleagues locate the main town of Ocute at the Shoulderbone mound site, northwest of Sparta, Georgia. Subsequent archaeological research has weakened this identification, as the site's population had declined by the mid-16th century, but it remains the best fit of the currently known sites.[5][6] Altamaha was located downstream to the south at the Shinholser site. Cofaqui was to the north, evidently at the Dyar site near Greensboro.[7][8] Ocute spoke a language later known as Yamasee, apparently a Muskogean tongue that may have been similar to Hitchiti.[9][10]

Another chiefdom possibly associated with Ocute, Ichisi, was located to the southwest, along the Ocmulgee River at the Lamar Mounds and Village Site.[11] Further southeast were smaller chiefdoms including Toa and Capachequi.[12] The Guale lived on the Georgia coast to the southeast, downstream from Ocute.[13] Northwest of Ocute was the much larger paramount chiefdom of Coosa; also to the north was a chiefdom at the Savannah River headwaters whose name is unknown.[14] To the west lay a vast uninhabited area on both sides of the Savannah River that Spanish chroniclers referred to as the "desert of Ocute" or the "wilderness of Ocute". Beyond the wilderness were Ocute's great enemies, the chiefdom of Cofitachequi in present-day South Carolina.[15] In earlier times the Savannah River had been densely populated and home to sizable chiefdoms, though it was entirely abandoned by about 1450, apparently due to the conflict between Ocute and Cofitachequi.[16]

Judging by the organization of other paramount chiefdoms like Coosa and Cofitachequi, Hudson argues that Ocute's power may have extended beyond the core Oconee province. He suggests Ocute's sphere included Ichisi, as well as the Guale and the unknown chiefdom at the Savannah River headwaters. Ocute and Ichisi were both located on tributaries of the Altamaha River, home to the Guale, and alliances to the north and south would have given Ocute relative parity with their enemies, the Cofitachequi. Hudson also entertains the possibility that Toa, perhaps on the Flint River, was included.[17]

Archaeology and early history

The area first saw substantial population around A.D. 150, during the Middle Woodland period. At least three mound centers – Cold Springs, Little River, and Lingerlonger – developed, along with smaller settlements. The inhabitants had similar ceramics styles and there is little evidence of corn agriculture.[18] During the Late Woodland period, the mound sites were abandoned and the population dispersed. Inhabitants developed simple pottery known as Vining Stamped ware, and primarily lived in small, corn-farming homesteads in and around the Oconee valley.[19]

Around 1100 the Mississippian culture took hold in the Oconee province. Inhabitants abandoned the old homesteads for new settlements near the river, taking advantage of the rich floodplain soils well suited for corn. Ceramics styles shifted to "complicated stamped" pottery, and the residents established mound centers, starting by reoccupying the Middle Woodland period Cold Springs mound. This was apparently the first chiefdom in the Oconee valley, although the town evidently relocated to the Dyar site around 1200 and then to the Scull Shoals site in about 1275. Also around 1275, a second, probably independent chiefdom developed at the Shinholser site 55 miles south. This local phase of Mississippian culture is known as the Savannah period.[20] A third chiefdom arose around 1325. Located at a new mound center, the Shoulderbone site, it was almost exactly equidistant to the other two.[21] Hudson identifies this site with Ocute.[22]

The Shoulderbone site is 8 miles east of the Oconee River along a key trail to the Savannah River, suggesting its location may have been chosen to trade with or defend against people to the east.[23] For a time, the Oconee province interacted with the Savannah Valley chiefdoms. These chiefdoms thrived in the 14th and 15th centuries, but were abandoned entirely by 1450, with at least part of the population moving west into the Oconee province.[24] It appears that increasing enmity with the South Carolina paramount chiefdom eventually known as Cofitachequi was a major factor driving the abandonment of the Savannah. This created the "wilderness of Ocute", which served as a buffer zone against Cofitachequi.[25] From about 1350, farmsteads expanded rapidly and the people adopted more complex coiled ceramics, marking the start of the Lamar phase of the culture.[26] The agricultural expansion and the formation of the eastern buffer may signal that all the Oconee polities were integrating into a paramount chiefdom in this period.[27]

De Soto expedition

By 1500, the population had expanded considerably. There were at least five mound centers (although the Shoulderbone site's population had declined dramatically) and several hundred smaller towns and other settlements.[28] Ocute enters the historical record in the chronicles of the expedition of Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto, which came through the chiefdom in 1539 on its way to Cofitachequi. They had learned about Ocute from two young men they had captured in Apalachee in present-day Florida.[29]

De Soto came to the chiefdom of Ichisi on March 25, 1539, and told the locals he would be merciful if their chief submitted.[30] He visited two small towns and entered the main town of Ichisi, at the Lamar Mounds and Village Site, on March 30. The chief of Ichisi cooperated fully, and informed the Spanish about the nearby paramount chief, Ocute. De Soto erected a wooden cross on one of the mounds before heading to Ocute.[31]

On April 3, the Spanish approached the chiefdom of Altamaha, led by a chief named Zamuno, who always bore arms in case of attack by Cofitachequi. It is unclear if De Soto entered the main town at the Shinholser site. Zamuno exchanged gifts with De Soto and asked if he should pay tribute directly to him, instead of to his overlord Ocute. De Soto replied that the previous relationship should stand.[32] De Soto erected a cross and left behind a cannon somewhere in the chiefdom. He summoned the paramount chief of Ocute, and then visited his main town, apparently at the Shoulderbone site, on April 9. He received gifts and set up another cross, and the army rested for two days.[33] On April 12, De Soto visited another subject chiefdom, Cofaqui, which was governed by a young noble named Patofa on behalf of his elderly uncle. Patofa reiterated his compatriots' policy of amity and gave the army provisions and porters.[34]

De Soto then determined to set out for Cofitachequi. The people of Ocute explained that the great wilderness separated them, and that no one alive had ever crossed it due to the war, despite what De Soto's guide had claimed. Nevertheless, the army departed on April 13.[35]

La Tama and later history

The paramount chiefdom changed substantially in the late 16th century. A large impetus was apparently the founding of Spanish St. Augustine in 1565, which caused Indian polities to realign in response to the new regional power center. Ocute's population dispersed from the mound centers in favor of decentralized farmsteads, and some began migrating into Spanish Florida. The mounds themselves were no longer used after about 1580. However, the total population continued increasing until about 1600.[36] In this period, Altamaha eclipsed Ocute as the paramount town; contemporary Spanish records refer to the province as "La Tama", derived from Altamaha.[37]

The Spanish sent several expeditions to La Tama between 1597 and 1628, beginning with a Franciscan mission that hoped to proselytize the province. The mission was warmly received in Altamaha, where the people nominally accepted Christianity. At Ocute, however, the chief threatened to kill them if they proceeded, invoking De Soto's invasion, and Altamaha also became hostile, so the mission returned to Spanish territory.[38] A military venture in 1602 found La Tama to be a fertile, populous province, and the chief of La Tama visited Spanish Governor Pedro de Ibarra in Guale in 1604.[39] The Spanish determined La Tama would be a valuable region to colonize, but never realized their plans to do so.[40]

In the 1620s, the Spanish sent five military expeditions to investigate rumors of mines and other Europeans in the interior, but only two reached La Tama, in 1625 and 1627. The first crossed the Wilderness of Ocute but was turned back at Cofitachequi due to the old war, while the second was allowed into Cofitachequi. After this, Spanish expansion efforts focused on the Timucua and Apalachee provinces west of St. Augustine rather than Georgia.[41]

Decline and the Yamassee confederacy

By around 1630, European diseases struck the province, and the population began to decline precipitously. In 1661 and 1662, Guale and Tama were raided by the Westo, a group allied to the English who used flintlock muskets and were heavily involved in the Indian slave trade. Many La Tama people were enslaved, and the rest abandoned the Oconee valley entirely.[42][43] Some survivors scattered to the nearby Muskogean and Escamacu chiefdoms, while others fled to the provinces of the Guale, Apalachee, and Timucua in Spanish Florida. Thereafter, they were among the peoples who became known as the Yamasee, who numbered between 700 and 800 in Florida in 1682.[44][45]

In the Guale and Timucuan Mocama provinces, La Tama refugees established four towns descended from the ancient interior Georgia chiefdoms: Altamaha, Okatee (Ocute), Chechessee (Ichisi), and Euhaw (apparently descended from Toa); Altamaha remained the leading town. Within the Yamassee confederacy, these towns formed the Lower Yamassee, while Guale towns and some others formed the Upper Yamassee.[46][45] The Yamaseee shifted alliances and later relocated to present-day South Carolina in 1685.[47] They remained a significant power in the Southeast until the English defeated them in the Yamasee War of 1715–1717, after which they integrated into the multiethnic settlements in Spanish Florida.[45][48]

Notes

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p. 30.

- ↑ Hudson 1994, p. 82.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Williams, p. 179–180.

- ↑ Hudson 1994, p. 82.

- ↑ Hudson 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ Hudson 1994, p. 82.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 180, 183.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p. 174.

- ↑ Hann 1989, pp. 187–189.

- ↑ Hudson 2009, p. 178.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p. 148.

- ↑ Hudson 2009, p. 178.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p. 165.

- ↑ Hudson 1997 165–172.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Hudson 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ Williams, p. 186.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Williams, p. 187.

- ↑ Williams, p. 189.

- ↑ Hudson 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Williams, p. 184, 190

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, 152–153.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Williams, p. 191.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p 158–159.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p 160–162.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 162–164.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, p. 165.

- ↑ Hudson 1997, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Green, DePratter, and Southerlin, p. 16.

- ↑ Worth 1994, pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Worth 1994, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Worth 1994, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Worth 1994, pp. 111–115.

- ↑ Williams, p. 193.

- ↑ Green, DePratter, and Southerlin, p. 16.

- ↑ Green, DePratter, and Southerlin, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 3 Worth 1999.

- ↑ Green, DePratter, and Southerlin, p. 15–17.

- ↑ Green, DePratter, and Southerlin, p. 19–20.

- ↑ Hann 1989, pp. 180–181.

References

- Ethridge, Robbie (2010). From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807834350.

- Green, William; DePratter, Chester B.; Southerlin, Bobby (2002). "The Yamassee in South Carolina: Native American Adaptation and Interaction along the Carolina Frontier". In Joseph, J. W.; Zierden, Martha. Another's Country: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Cultural Interactions in the Southern Colonies. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817311297. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- Hann, John (October 1989). "St. Augustine's Fallout from the Yamasee War". The Florida Historical Quarterly. Florida Historical Society. 68 (2): 180–200. JSTOR 30148065.

- Hudson, Charles (1994). "The Hernando de Soto Expedition, 1539–1543". In Hudson, Charles; Tesser, Carmen Chaves. The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704. University of Georgia Press. pp. 74–103. ISBN 0820316547.

- Hudson, Charles (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820320625.

- Hudson, Charles (2009). "The Social Context of the Chiefdom of Ichisi". In Hally, David J. Ocmulgee Archaeology, 1936-1986. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820316062.

- Smith, Marvin T. (May 1994). Archaeological Investigations at the Dyar Site, 9GE5 (PDF). University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology Series, Report Number 32. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- Williams, Mark (1994). "Growth and Decline of the Oconee Province". In Hudson, Charles; Tesser, Carmen Chaves. The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704. University of Georgia Press. pp. 179–196. ISBN 0820316547.

- Worth, John E. (1994). "Late Spanish Military Expeditions in the Interior Southeast, 1597–1628". In Hudson, Charles; Tesser, Carmen Chaves. The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704. University of Georgia Press. pp. 104–122. ISBN 0820316547.

- Worth, John E. (1999). Yamassee Origins and the Development of the Carolina-Florida Frontier (PDF). Paper presented at the Fifth Annual Conference of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. Austin, Texas.