Joara

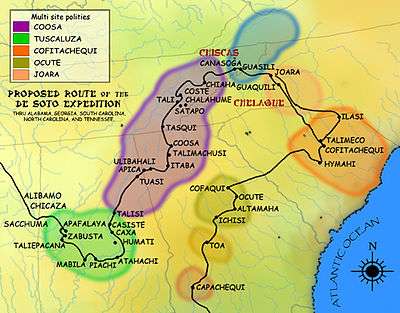

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina, about 300 miles in the interior in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[1] Joara is notable as a significant archaeological and historic site. It was a place of encounter in 1540 between the Mississippian people and the party of Spanish conquistador Hernando De Soto.[2]

A later expedition under Juan Pardo in 1567 created the first brief European settlement in the interior of the continent, establishing Fort San Juan at this site, together with other forts to the west.[2] It is thought to be the first and the largest of the forts that Pardo established in an attempt to colonize the American South[3] On July 22, 2013, archeologists announced evidence of the long-suspected Fort San Juan at Joara, after previous excavations revealed European as well as Mississippian artifacts.[1]

History

In the 21st century, archaeological finds from excavations have established evidence of both substantial Mississippian and sustained Spanish 16th-century settlement in the interior of North Carolina. Joara was also the site of Fort San Juan, established by the Juan Pardo expedition as the earliest Spanish outpost (1567–1568) in the interior of what is now North Carolina. This was 40 years before the English settlement at Jamestown and nearly 20 years before their "Lost Colony" at Roanoke Island.[2]

Located northwest of Morganton, the site has been excavated in portions by the Upper Catawba Valley Archaeology Project since the early 2000s. They hold regular open houses and educational events for the public during the summer excavation season.

Established about AD 1000, Joara was the largest Mississippian culture settlement within the current boundaries of North Carolina.[4] In 1540 a party of Spanish conquistador Hernando De Soto encountered the people at this chiefdom site.[2] It was still thriving in January 1567 when the Spanish soldiers under Captain Juan Pardo arrived. Pardo established a base there for the winter, called the settlement Cuenca, and built Fort San Juan. After 18 months, the natives killed the soldiers at the fort and burned the structures down. That same year the natives destroyed all six forts in the southeast interior and killed all but one of the 120 men Pardo had stationed in them. As a result, the Spanish ended their colonizing effort in the southeastern interior.[4]

Effects of European infectious diseases and conquest, and assimilation by larger native tribes, led to native abandonment of the settlement long before English explorers arrived in the region in the 17th century. De Soto's 1540 expedition noted the Chalaque already in the area at the time. According to some modern-day conjectures, the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, migrated into western North Carolina from northern areas around the Great Lakes and used some of the former Mississippian village sites. English, Scots-Irish and German immigrants arrived in the 18th century.

Settlement

Joara is thought to have been settled some time after AD 1000 by the Mississippian culture, which built an earthwork mound at the site. It was a regional chiefdom, established on the west bank of Upper Creek and within sight of Table Rock, a dominant geographical feature of the area. The Joara natives comprised the eastern extent of Mississippian Mound Builder culture, which was centered in the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys. By the time of the first European contact by the Spanish with Native Americans in the foothills of the southern Appalachians, Joara had already grown to be the largest Mississippian-culture settlement in present-day North Carolina. The town served as the political center of a regional chiefdom that controlled many of the surrounding native settlements.[4]

Most contemporary scholars, following John Swanton, connect the various spellings of Joara with the Cheraw, a Siouan language-speaking people. The later historic Catawba Nation are likely descendants of the natives at Joara.[5]

Cofitachequi and the neighboring Coosa chiefdoms were developed by ancestral Muskogean-speaking groups, who apparently claimed other areas as tributary. The Creek people are their descendants. The scholar T.H. Lewis at first associated the term Xualla with the modern Qualla Boundary and thought it was Cherokee, but most modern scholars no longer believe this. Charles Hudson alone among modern scholars argues that Joara may be a Cherokee name; but the Cherokee were not moundbuilders and were not the first to develop the site.[6]

Spanish exploration

Hernando de Soto

In 1540, Hernando de Soto led a Spanish army up the eastern edge of the Appalachian mountains through present-day Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. This expedition recorded the first European contact with the people of Joara, which de Soto's chroniclers called Xuala.[7] De Soto brought the queen of Cofitachequi province to Joara as an involuntary member of his entourage. The chroniclers also state that the queen claimed political dominion at this time over Joara province as well as the province of "Chalaque", and that the natives in both places respected her office. She managed to escape after reaching Joara.

The Spanish departed to continue their exploration of Spanish Florida's interior, crossing westward over the Blue Ridge into eastern Tennessee, where they visited the Coosa chiefdom at Guasile. It would be another 26 years before the Spanish would return under the Juan Pardo Expedition to try to enforce their claim over the land and its native inhabitants.

Captain Juan Pardo's first expedition

On December 1, 1566, Captain Juan Pardo and 125 men departed from Santa Elena, a center of Spanish Florida (located on present-day Parris Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina) under orders from Governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to claim the interior for Spain. Pardo was to pacify the native inhabitants, convert them to Catholicism, and establish a route to Spanish silver mines near Zacatecas, Mexico. The Spanish thought they were much closer to the mines than they were in fact.

To stay close to food sources on their journey through the foothills, the Spanish traveled northwest where there were friendly natives who would help to feed them. The small Spanish force stopped at Otari (near present-day Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina) and Yssa (near present-day Denver, Lincoln County), before arriving at Joara.

Captain Pardo and his men arrived at Joara in January 1567. He renamed it Cuenca after his hometown of Cuenca, Spain. Snow in the Appalachian Mountains forced the Spanish to establish a winter base in the foothills at Joara. According to the records of the expedition, the explorers built a wooden fort at the north end of Joara and named it Fort San Juan. The fort became the first European settlement of present-day North Carolina, predating the establishment of the first English colony at Roanoke Island by 18 years and Jamestown Virginia by 40 years.

The Spanish kept a base in Fort San Juan and claimed sovereignty over several other settlements in the region, including Guaquiri (near present-day Hickory, Catawba County, North Carolina) and Quinahaqui (in present-day Catawba County, North Carolina). In February 1567, Captain Pardo established Fort Santiago at Guatari, a smaller town of Guatari (also called Wateree) natives located in present-day Rowan County, North Carolina.

When Captain Pardo received word of a possible French invasion of Santa Elena (an early Spanish mission on the coast), he left 30 soldiers to occupy Joara, and four soldiers and his chaplain, Sebastián Montero, to occupy Guatari. He departed the area with the remainder of his force. Pardo appointed sergeant Hernando Moyano to command the force stationed at Fort San Juan.

Hernando Moyano's raids

During the spring of 1567, Hernando Moyano led a combined force of natives and Spanish north. The force attacked and burned the Chisca tribe's village of Maniateque (near present-day Saltville, Virginia) before returning to Joara.

After resting and supplying his force, Moyano led his force to Guapere (thought to be on the upper Watauga River in present-day Tennessee). The Spanish and native force attacked and burned Guapere and marched west to Chiaha (also in present-day Tennessee). Moyano's force built a fort in Chiaha and waited for Captain Juan Pardo to return.

Captain Juan Pardo's second expedition

Captain Juan Pardo returned to Fort San Juan in September 1567 to find the local inhabitants angered by the Spanish raids and demands for food, women, and canoes. The effect of newly introduced diseases was also destabilizing the community, causing resentment towards the Spanish. Instead of continuing his mission to Mexico, Captain Pardo left a garrison at Fort San Juan and marched the remainder of his troops westward to resupply Sgt. Hernando Moyano's troops.

Pardo first took his troops to the native village of Tocae (near present-day Asheville, North Carolina), then continued to Cauchi (near present-day Canton, North Carolina. The force continued on to Tanasqui and then to Chiaha where they found Hernando Moyano's troops in need of supply. After resupplying Moyano's troops, Pardo returned to Santa Elena.

Native uprising and end of Spanish colonization

Shortly after May 1568, news reached Santa Elena that the native population had burned the six Spanish forts established by Juan Pardo and killed all but one of the 120 Spanish men stationed in those garrisons. Captain Pardo never returned to the area, and Spain ended all attempts to conquer and colonize the southeastern interior. Captain Juan Pardo's narrative of his travels and settlement at Joara, written by his scribe Bandera, were discovered and translated into English in the 1980s. They have contributed to a significant reassessment of the history of Spanish colonization in the interior of North America.[8]

Demise and abandonment

At the time of the first Spanish contact, the native people of the area were identified by their villages of residence and were not part of large tribes. Death from European diseases and conquest and assimilation by large tribes such as the Catawba and Cherokee caused many of these smaller native groups to disappear.

In 1670, explorer John Lederer, departing from Fort Henry, explored deep into North Carolina and described a large town he called "Sara", in the mountains that "receive from the Spaniards the name of Suala". He states that the natives here mined cinnabar to make purple facepaint, and had cakes of salt. James Needham and Gabriel Archer also explored the entire area from Fort Henry in 1671, and described this town as "Sarrah". However, this was likely several miles to the east of the original Joara.

By the time most English, Moravian, Scots-Irish, and German settlers arrived in the area in the 18th century, Joara and many of the other native towns in the region had been abandoned.

Although the location of Joara and Fort San Juan were forgotten, local inhabitants found numerous native artifacts in certain areas of the upper Catawba River Valley. Unlike areas in which mounds were protected, during the early 1950s farmers bulldozed Joara's twelve-foot-high earthen platform mound to make way for cultivation.[8] The location of the mound is now recognizable only as a two-foot rise in the field but current owners vow to protect the site.

Rediscovery at the Berry site

During the 1960s and 1970s, several archaeological surveys were conducted in Burke County to determine possible locations of Joara and Fort San Juan. By the 1980s, archaeologists had reduced the number of possible locations and began limited excavations. These surveys and excavations showed that the upper Catawba River Valley did have a sizable native population during the 14th to 16th centuries.

In 1986, a breakthrough occurred at the Berry excavation site (named for the family who own the property). Archaeologists discovered 16th-century Spanish artifacts. This evidence, supported by Bandera's 16th century narrative, caused a reevaluation of Pardo's route through the Upper Catawba Valley. Further evidence suggests the Berry Site is the location of Joara and Fort San Juan.[9] The archaeological site has demonstrated the extent to which the Spanish attempted to establish a colonial foothold in the interior of the Southeast.[8]

Further excavations at the Berry site throughout the 1990s and 2000s have yielded remains of native Joara settlement and burned Spanish huts, and more 16th-century Spanish artifacts, including olive jar fragments, a spike, and a knife. In 2007, the team excavated Structure 5 and found a Spanish iron scale, as well as evidence of Spanish building techniques. These artifacts were not trade goods but objects used by the Spanish in settlements. Joara is particularly interesting for the interaction between Native Americans and Spanish, who were relatively few in number and depended on the natives for food. Archaeologists expect to find evidence that will reveal more about events there.[9][10]

Archaeologists familiar with the area have concluded this is the site of Joara and Fort San Juan. It supports documented Spanish settlement of 1567–1568, as well as the natives' burning of the fort. The discovery is requiring a reassessment of the history of European contact with Native Americans.[4]

In July 2013, archeologists reported finding evidence of the remains of the fort itself at the site, including the remnants of burned palisades and what appeared to be the main structure within the fort.[11]

See also

- Saura

- Xualae

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

- Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

- List of Mississippian sites

- Bussell Island

Citations

- 1 2 John Noble Wilford, "Fort Tells of Spain’s Early Ambitions", New York Times, 22 July 2013, accessed 22 July 2013

- 1 2 3 4 David G. Moore, Robin A. Beck, Jr., and Christopher B. Rodning, "Joara and Fort San Juan: culture contact at the edge of the world", Antiquity, Vol.78, No.229, Mar. 2004, accessed 26 Jun 2008

- ↑ Medieval Spanish gold hunters’ fort found in North Carolina

- 1 2 3 4 David Moore, Robin Beck and Christopher Rodning, "In Search of Fort San Juan: Sixteenth Century Spanish and Native Interaction in the North Carolina Piedmont", Warren Wilson College Archaeology Home Page, 2004, accessed 26 Jun 2008,

- ↑ Dr. Robin Beck, et al., "Joara and Fort San Juan: Colonialism and Household Practice at the Berry Site, North Carolina", Tulane University, National Science Foundation grant abstract, 7 Sept 2006

- ↑ Charles Hudson, 1998, Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando De Soto...

- ↑ Charles Hudson, The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Explorations of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566–1568 (Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2005), 25.

- 1 2 3 Catherine Clabby, "Dig finds evidence of Spanish fort", News Observer, 1 Aug 2004, accessed 26 Jun 2008

- 1 2 Constance E. Richards, "Contact and Conflict", American Archaeologist, Spring 2008, p.14

- ↑ Martha Quillin, "Trove from Fort San Juan delights archaeologists", The News Observer, 31 Jan 2008, accessed 26 Jun 2008

- ↑ "First New World Fort Was Spain’s", John Wilford, New York Times, July 22, 2013

References

- Beck, Robin A., Jr. (Winter 1997). "From Joara to Chiaha: Spanish Exploration of the Appalachian Summit Area, 1540-1568". Southeastern Archaeology. 16 (2): 162–169.

- Beck, Robin A., Jr.; David G. Moore (Winter 2002). "The Burke Phase: A Mississippian Frontier in the North Carolina Foothills". Southeastern Archaeology. 21 (2): 192–205. ISSN 0734-578X.

- Beck, Robin A., Jr.; David G. Moore; Christopher B. Rodning (Summer 2006). "Identifying Fort San Juan: A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Occupation at the Berry Site, North Carolina". Southeastern Archaeology. 25 (1): 65–77. ISSN 0734-578X.

- Clabby, Catherine (Aug. 1, 2004). "Dig finds evidence of Spanish fort". The News and Observer.

- Moore, David G.; Beck, Robin A. Jr.; & Rodning, Christopher B. (March 2004). "Joara and Fort San Juan: culture contact at the edge of the world", Antiquity (Vol 78 No 299).

- Moore, David; Beck, Robin; & Rodning, Christopher (Jun. 30, 2004). "In Search of Fort San Juan: Sixteenth Century Spanish and Native Interaction in the North Carolina Piedmont". Warren Wilson Archaeological Field School.

- Rudes, Blair A. (Winter 2004). "Place Names of Cofitachequi". Anthropological Linguistics. 46 (4): 359–426. ISSN 0003-5483.

- Simmons, Geitner (Aug. 15, 1999). "Insight". The Salisbury Post. Retrieved Jul. 7, 2005.

- Simmons, Geitner (Aug. 29, 1999). "Spanish empire failed to conquer Southeast". The Salisbury Post. Retrieved Jul. 7, 2005.

External links

Coordinates: 35°47′45″N 81°43′01″W / 35.7959°N 81.7170°W