Thiruvilaiyadal

| Thiruvilaiyadal | |

|---|---|

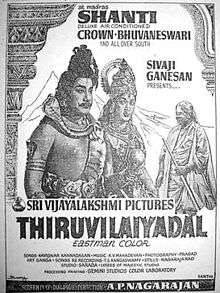

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | A. P. Nagarajan |

| Produced by | A. P. Nagarajan |

| Based on |

Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam by Paranjothi Munivar |

| Starring | |

| Music by | K. V. Mahadevan |

| Cinematography | K. S. Prasad |

| Edited by |

|

Production company |

Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures |

| Distributed by | Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures |

Release dates | 31 July 1965 |

Running time | 155 minutes[1] |

| Country | India |

| Language | Tamil |

Thiruvilaiyadal (English: The Divine Game) is a 1965 Indian Tamil-language Hindu devotional film written, directed, produced, and distributed by A. P. Nagarajan. The film features Sivaji Ganesan, Savitri, and K. B. Sundarambal in the lead roles with T. S. Balaiah, R. Muthuraman, Nagesh, T. R. Mahalingam, K. Sarangapani, Devika, Manorama, and Nagarajan himself playing pivotal roles. The film's soundtrack and score were composed by K. V. Mahadevan, while the lyrics of the songs were written by Kannadasan and Sankaradas Swamigal.

The story of Thiruvilaiyadal was conceived by A. P. Nagarajan, who was inspired by the Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam, a collection of sixty-four Shaivite, devotional, epic stories written in the 16th century by the saint, Paranjothi Munivar, which record the actions and antics of Lord Shiva appearing on Earth in various disguises to test his devotees. Four of the sixty-four stories are depicted in the film. The first is about the poet Dharumi; the second concerns Dhatchayini (Sati). The third recounts how Shiva's future wife Parvati is born as a fisherwoman and how Shiva, in the guise of a fisherman, finds and remarries her. The fourth story is that of the singer Banabhathirar. The soundtrack was received positively and songs from it like "Pazham Neeyappa", "Oru Naal Podhuma", "Isai Thamizh", and "Paattum Naane" remain popular today among the Tamil diaspora.

Thiruvilaiyadal was released on 31 July 1965 to critical acclaim, with praise directed at the film's screenplay, dialogue, direction, music, and the performances of Ganesan, Nagesh, and Balaiah. The film was a commercial success, running for over twenty-five weeks in theatres, and became a trendsetter for devotional films as it was released at a time when Tamil cinema primarily produced social melodramas. It won the Certificate of Merit for the Second Best Feature Film in Tamil at the 13th National Film Awards, and the Filmfare Award for Best Film – Tamil. The film was dubbed into Kannada as Shiva Leela Vilasa, the first Tamil film to be dubbed into Kannada in ten years. A digitally restored version of Thiruvilaiyadal was released in September 2012, which was also a commercial success.

Plot

Lord Shiva gives a sacred Mango fruit, brought by the sage Narada, to his elder son Vinayaka as a prize for outsmarting his younger brother Muruga in a competition to win it. Angered by his father's decision, Muruga, dressed as a hermit, goes to Palani, despite Avvaiyar's attempts to convince him to return to Mount Kailash. His mother, goddess Parvati, arrives there and narrates the stories of four of Shiva's divine games to calm Muruga.

The first story is about the opening of Shiva's third eye when he visits Madurai, the capital city of the Pandya Kingdom, ruled at that time by Shenbagapandian. Shenbagapandian wants to find the answer to a question posed by his wife — whether the fragrance from a woman's hair is natural or artificial — and announces a reward of 1000 gold coins to anyone who can come up with the answer. A poor poet named Dharumi desperately wants the reward and starts to break down in the Meenakshi Amman Temple. Shiva, hearing his cries, takes the form of a poet and gives Dharumi a poem containing the answer. Overjoyed, Dharumi takes the poem to Shenbagapandian's court and recites it, but Nakkeerar, the court's head poet, claims the poem's meaning is incorrect. On hearing this, Shiva argues with Nakkeerar about the poem's accuracy, burning him to ashes when he refuses to relent. Later, Shiva revives Nakkeerar, and says that he only wanted to test his knowledge. Nakkeerar asks the king to give the reward to Dharumi.

The second story focuses on Shiva marrying Dhatchayini against the will of her father Dhatchan. Dhatchan performs a Mahayajna without inviting his son-in-law. Dhatchayini asks Shiva's permission to go to the ceremony, but Shiva refuses to let her go as he feels no good will come from it. Dhatchayini disobeys him and goes only to be insulted by Dhatchan. Dhatchayini curses her father and returns to Shiva who is angry with her. Dhatchayini asserts that they are one and without her, there is no Shiva. He refuses to agree with her and burns her to ashes. He then performs his Tandava, which is noticed by the Devas, who pacify him. Shiva then restores Dhatchayini to life and accepts that they are one.

The third story describes Parvati being banished by Shiva when she becomes momentarily distracted while listening to his explanation of the Vedas. Parvati, now born as Kayarkanni, is the daughter of a fisherman. When playing with her friends, Shiva approaches in the guise of a fisherman and flirts with her, despite her disapproval. The fishermen often face problems due to a giant shark that disrupts their way of life. Shiva asserts that he alone can defeat the shark. After a long battle, Shiva subdues the shark (which is actually Nandi in disguise) and remarries Parvati.

The last story is that of Banabathirar, a devotional singer. Hemanatha Bhagavathar, a skilled singer, tries to conquer the Pandya Kingdom when he challenges the kingdom's musicians. The King's minister advises him to seek Banabathirar's help to challenge Hemanatha Bhagavathar. When all the musicians reject the competition, the King orders Banabathirar to compete against Hemanatha Bhagavathar. Knowing that he cannot win, the troubled Banabathirar prays to Shiva who shows up outside Hemanatha Bhagavathar's house in the form of a firewood vendor the night before the competition, and shatters his arrogance by singing the song "Paattum Naane". Shiva introduces himself to Hemanatha Bhagavathar as Banabathirar's student. Sheepish upon hearing this, Bhagavathar leaves the kingdom immediately, informing Banabathirar of his departure with a note. Shiva gives the letter to Banabathirar and reveals his true identity to him. Banabathirar thanks Shiva for helping him.

After listening to these stories, Muruga's rage finally subsides and he reconciles with his family. The film ends with Avvaiyar singing "Vaasi Vaasi" and "Ondraanavan Uruvil" in praise of both Shiva and Parvati.

Cast

- Lead actors

- Sivaji Ganesan as Shiva

- Savitri as Parvati (also referred to as Uma, Sakthi, Dhatchayini and Kayarkanni in the film)

- K. B. Sundarambal as Avvaiyar

- Male supporting actors

- T. S. Balaiah as Hemanatha Bhagavathar

- R. Muthuraman as Shenbagapandian

- Nagesh as Dharumi

- O. A. K. Thevar as King Dhatchan

- A. Karunanithi as Ponna/Sovai

- T. R. Mahalingam as Banabhathirar

- A. P. Nagarajan as Nakkeerar

- K. Sarangapani as Kayarkanni's father

- Female supporting actors

Production

Development

We had to talk as we walked. We could not break up the dialogues for our convenience as that would slow down the tempo of the shot. We had such a degree of understanding that we enacted the scene with immaculate timing and with the required expressions in one continuous shot. It came out very well and is enjoyed by people even today.

– Sivaji Ganesan on his experience while filming with Nagesh, as quoted in the English edition of Autobiography of an Actor: Sivaji Ganesan, October 1928-July 2001.[2]

The first film where Sivaji Ganesan and A. P. Nagarajan collaborated was Naan Petra Selvam (1956).[3] The scene where the Tamil poet Nakkeerar confronts Shiva over an error in his poem, effectively exaggerating his sensitivity to right and wrong, laid the foundation for Thiruvilaiyadal.[4]

The story of Thiruvilaiyadal was conceived by Nagarajan.[5] The film was inspired from the Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam, a collection of sixty-four Shaivite devotional epic stories written in the 16th century by the saint Paranjothi Munivar, which record the actions and antics of Shiva appearing on Earth in various disguises to test his devotees.[6] Four of the sixty-four stories are depicted in the film.[7] Nagarajan produced and distributed the film under the banner of Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures. He wrote the screenplay in five parts, and made an appearance in the film as Nakeerar.[8] M. N. Rajan and T. R. Natarajan were the editors, while K. S. Prasad, Ganga and R. Rangasamy were the film's cinematographer, art director and Ganesan's make-up artist respectively.[9][10]

Savitri's portrayal of Goddess Parvati was the first instance of the deity being seen onscreen in a South Indian film.[11] Ganesan was cast as Shiva,[9] while K. B. Sundarambal was chosen to play Avvaiyyar, reprising her role from the 1953 film of the same name.[12][13] Nagesh, R. Muthuraman and T. S. Balaiah were cast as Dharumi, Shenbagapandian and Hemanatha Bhagavathar respectively,[9] while T. R. Mahalingam was cast as Banabhathirar.[14] Other supporting actors include Devika, Manorama, K. Sarangapani and O. A. K. Thevar.[15][16]

Filming

Thiruvilaiyadal was entirely shot in a specially erected set at Vasu Studios in Madras (now Chennai).[17] It was filmed in Eastmancolor and was Nagarajan's first colour film.[9][18] The scenes featuring the conversations between Shiva and Dharumi were not scripted by Nagarajan but were improvised during filming by Nagesh and Ganesan.[19]

Due to his busy schedule at that time, Nagesh had a call sheet of one and a half days to finish his portions.[17] When he learned that Ganesan's arrival was delayed because his make-up had not been completed, he asked Nagarajan whether they could film any solo sequences, which included a scene where Dharumi rants about his misfortune in the Meenakshi Amman Temple.[17] While filming, Nagesh spontaneously came up with the dialogue, "Varamaattan. Varamaattan. Avan nichchaiyam varamaattan. Enakku nalla theriyum. Varamaattan" (English: He won't come. He won't come. He will definitely not come. I know. He won't come).[17][20] According to Nagesh, he was inspired by two incidents: one that involved two assistant directors discussing whether Ganesan would be ready before or after lunch — one said he would be ready while the other said he would not. The other was when Nagesh happened to notice a passerby talking to himself about how the world had fallen on bad times.[17][20] The dubbing for the scenes featuring Nagesh and Ganesan was completed after the footage was shot. After viewing the sequences twice, Ganesan requested Nagarajan not to remove a single frame of Nagesh's portions from the final version of the film as he felt that they, along with Balaiah's scenes, would become a major highlight of the film.[20][21]

Thiruvilaiyadal was the first Tamil film since P. U. Chinnappa's Jagathalaprathapan (1944) to have the lead actor play five roles in one sequence. Ganesan does so in the song "Paattum Naane" where he plays the Veena, Mridangam, flute and Jathi; the fifth role has him singing.[22][23][24] R. Bharathwaj, writing for The Times of India, believes the story of the competition between Hemanatha Bhagavathar and Banabathirar to be comparable to a contest between Carnatic music composer Syama Sastri and Kesavvaya, a singer from Bobbili.[25][26] Sastri had sought divine intervention from the Goddess Kamakshi to defeat Kesavayya, mirroring Banabathirar's plea for Shiva's help.[26] When asked by his biographer T. S. Narayanawami about the Tandava he performed in the film, Ganesan simply replied that he learned the movements necessary for that particular situation and performed according to the choreographer's instructions.[27][28] The final length of the film was 4,450 metres (14,600 ft).[9]

Themes

The title of the film, Thiruvilaiyadal, is justified in the beginning of the film as a voiceover. It begins with salutation to the fans, and it quotes the literary epic of Shiva, Thiruvilaiyadal. The narrator briefs that whatever Shiva does, it is to test the patiece of his disciples and the god plays games which invokes more devotion in the minds of his worshippers. Hence the title symbolically means the games played by Shiva. By opening in media res, the film follows a nonlinear narrative.[29] According to Hari Narayan of The Hindu, Thiruvilaiyadal valorises the deeds of a god (Shiva) by narrating some miracles performed by him.[30]

Music

| Thiruvilaiyadal | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by K. V. Mahadevan | |

| Released | 1965 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Language | Tamil |

| Label | Saregama |

The soundtrack and score were composed by K. V. Mahadevan,[31][32] while the lyrics of the songs were written by Kannadasan, with the exception of the first portions of "Pazham Neeyappa", which were penned by Sankaradas Swamigal.[1] The soundtrack was released on the Saregama music label.[33] Every line in the song "Oru Naal Podhuma" belongs to a different raga.[34][35] Some of them include Darbar,[36] Todi,[37] Neelambari,[37] Mohanam and Kalyani.[35] "Pazham Neeyappa" is based on three ragas — Darbari Kanada,[38] Shanmukhapriya and Kambhoji.[39][40] "Isai Thamizh", "Paattum Naane" and "Illadhathondrillai" are based on the Abheri,[41] Gourimanohari and Simhendramadhyamam ragas respectively.[42][43] Vikku Vinayakram and Cheena Kutty were the Ghatam and Mridangam players for "Paattum Naane" respectively.[44][45] The "Macha Veena" seen in "Paattum Naane" was made by Subbiah Asari; the crew of Thiruvilaiyadal purchased it from him for ₹10,000 (equivalent to ₹470,000 or US$6,900 in 2016).[46]

The album received positive reviews from critics, and the songs "Pazham Neeyappa", "Oru Naal Podhuma", "Isai Thamizh" and "Paattum Naane" still remain popular among the Tamil diaspora.[22] Film historian Randor Guy, in his 1997 book Starlight, Starbright: The Early Tamil Cinema, identifies "Pazham Neeyappa" in particular, performed by Sundarambal, as the "favourite of millions".[47] The singer Charulatha Mani, writing for The Hindu, believed that Sundarambal had produced a "pure and pristine depiction" of the Neelambari raga in "Vaasi Vaasi", and expressed approval of M. Balamuralikrishna's rendition of "Oru Naal Podhuma".[36][37] Mana Baskaran of The Hindu Tamil described the album as: "an attractive package for all to listen to."[48] Following T. M. Soundararajan's death in May 2013, M. Ramesh of Business Line wrote, "The unforgettable sequences from ... Thiruvilaiyaadal ... has forever divided the world of Tamil music lovers into two: those who believe that the Oru naal poduma of the swollen-headed Hemanatha Bhagavathar could not be bested, and those who believe that Lord Shiva’s Paattum Naane Bhavamum Naane won the debate hands down." He praised Soundararajan's performance in "Paattum Naane", which he described as "stupefying".[49]

| Track list[31][32] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "Pazham Neeyappa" | K. B. Sundarambal | 06:29 |

| 2. | "Oru Naal Podhuma" | M. Balamuralikrishna | 05:28 |

| 3. | "Isai Thamizh" | T. R. Mahalingam | 03:50 |

| 4. | "Paarthal Pasumaram" | T. M. Soundararajan | 03:44 |

| 5. | "Paattum Naane" | T. M. Soundararajan | 05:54 |

| 6. | "Podhigai Malai Uchiyiley" | P. B. Sreenivas, S. Janaki | 02:52 |

| 7. | "Ondraanavan Uruvil" | K. B. Sundarambal | 03:04 |

| 8. | "Illadhathondrillai" | T. R. Mahalingam | 03:08 |

| 9. | "Vaasi Vaasi" | K. B. Sundarambal | 05:57 |

| 10. | "Om Namasivaya" | Sirkazhi Govindarajan, P. Susheela | 03:32 |

| 11. | "Neela Chelai Katti Konda" | P. Susheela | 04:40 |

Total length: |

45:30 | ||

Release

Thiruvilaiyadal was released on 31 July 1965.[50] During the screening in a Madras cinema house several women went into a religious frenzy during a sequence with Avvaiyar and Murugan. This led to the projection being temporarily suspended so that the women could be attended to.[47] According to artist V. Jeevananthan, the management of the Raja Theatre erected a set of Mount Kailash to promote the film.[51]

The film was a commercial success;[52] it ran for 25 weeks in Shanti, a theatre owned by Ganesan,[53] and ran for the same duration in the Crown and Bhuvaneshwari theatres in Madras and in theatres across South India.[54] It went on to have a total theatrical run of 26 weeks, thereby becoming a silver jubilee film.[52][lower-alpha 1] The film contributed to Ganesan's long string of successful films.[55]

Thiruvilaiyadal was dubbed into Kannada as Shiva Leela Vilasa, making it the first Tamil film to be dubbed in the language since 1955 as there was a ban on dubbing other language films into Kannada.[lower-alpha 2]

Critical reception and accolades

Thiruvilayadal received critical acclaim, garnering the Certificate of Merit for the Second Best Feature Film in Tamil at the 13th National Film Awards.[56] It also won the Filmfare Award for Best Film – Tamil.[57] Critics applauded the screenplay, dialogue, direction, music, and the performances of Ganesan, Nagesh and Balaiah.[52] The Tamil magazine Kalki, in a review dated 22 August 1965, considered the film to be "a victory for Tamil cinema",[58] while Mana Baskaran of The Hindu Tamil appreciated the way Nagarajan blended contemporary social issues into a devotional film, opining that the costume and set designs "gave a new dimension to film making in Tamil cinema."[48] Ananda Vikatan, in a review dated 28 August 1965, appreciated the film and noted: "When social films have started dominating Tamil Cinema, it is a welcome change to see a very good devotional film like this which made everyone happy. The film deserves another viewing."[59]

M. Suganth and Karuna Amarnath of The Times of India praised Ganesan for displaying versatility through Shiva's various appearances in the film, and called it a "must watch".[33] The actor and film historian Mohan V. Raman was enthusiastic about Balaiah's performance in "Oru Naal Podhuma", believing his screen presence to have been instrumental in the success of the film.[60] S. Theodore Baskaran gave a rather mixed review, describing his experience seeing the film as "watching a merely photographed drama",[61] but appreciated Nagesh's performance: "If there is just one role that he is remembered for, it is this."[62] Baskaran also appreciated Ganesan's dialogue delivery during the scene where his character argues with Nakkeerar.[63] Subha J. Rao and K. Jeshi of The Hindu, in their article "Laughter lines", highlighted the way that Nagesh "brings the house down as the impoverished poet."[64] Following Manorama's death in October 2015, The New Indian Express ranked Thiruvilaiyadal eighth in their list of "Top Movies" featuring her.[65]

Legacy and influence

| “ | Only two actors can pull the scene away from under my feet when we face the camera together — one is M. R. Radha, the other, Nagesh. | ” | |

| — Ganesan while listening to an audio version of Thiruvilaiyadal[66] | |||

Thiruvilaiyadal has attained cult status in Tamil cinema.[9] It was a landmark film in reviving public interest in devotional films and became the definitive film of the genre at a time when social melodramas dominated Tamil cinema.[59] Many critics consider Thiruvilaiyadal to be Nagarajan's greatest work,[52] with film critic Baradwaj Rangan calling it "the best" of the epic Tamil films.[67] Nagarajan and Ganesan went on to collaborate on several more films in the same genre, including Saraswati Sabatham (1966), Thiruvarutchelvar (1967), Kandhan Karunai (1967) and Thirumal Perumai (1968),[52] Other notable films that followed the trend set by Thiruvilaiyadal include Sri Raghavendrar (1985) and Meenakshi Thiruvilayadal (1989).[68][69] Thiruvilaiyadal became a milestone in Nagesh's career and the character of Dharumi is cited as one of his best roles to date.[66][70]

Director Boopathy Pandian's Thiruvilaiyaadal Aarambam (2006) was initially titled Thiruvilayadal, but this was changed after an outburst of objections from Ganesan's fans.[71][72] In July 2007, when S. R. Ashok Kumar of The Hindu asked eight acclaimed directors to list ten films they liked most, Thiruvilaiyadal was chosen by C. V. Sridhar and Ameer. The latter found the film to be "imaginative" and that it depicted the mythological genre in "an interesting way." Ameer concluded by calling it "one of the best films in the annals of Tamil cinema."[73] Following Nagesh's death in 2009, Sify ranked Thiruvilaiyadal fifth in its list, "10 Best Films of late Nagesh", commenting that he "was at his comic best in this film".[74] Thiruvilaiyadal is included along with other Sivaji Ganesan films in 8th Ulaga Adhisayam Sivaji, a compilation DVD featuring Ganesan's "iconic performances in the form of scenes, songs and stunts" which was released in May 2012.[75]

Thiruvilaiyadal has been parodied and referenced in various media such as cinema, television and theatre. Notable films that allude to Thiruvilaiyadal include Netrikkann (1981),[76] Poove Unakkaga (1996),[77] Mahaprabhu (1996),[78] Kaathala Kaathala (1998),[79] Vanna Thamizh Pattu (2000),[80] Middle Class Madhavan (2001),[81] Kamarasu (2002),[82] Vanakkam Thalaiva (2005),[83] Kanthaswamy (2009),[84] and Oru Kal Oru Kannadi (2012).[85] In his review of Oru Kanniyum Moonu Kalavaanikalum (2014), Baradwaj Rangan likened the way Shiva plays his divine games by intervening in human affairs in Thiruvilaiyadal to the use of touchscreen human face icons on mobile apps.[86]

The Star Vijay comedy series Lollu Sabha made two parodies on the film; once in an episode of the same name,[87] and a contemporary version titled "Naveena Thiruvilayaadal".[88] In April 2008, Raadhika launched a television series titled Thiruvilaiyadal, which covers all sixty-four stories in the Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam, unlike the film which covered only four.[89] In April 2012, Pavithra Srinivasan of Rediff included the film in her list, "The A to Z of Tamil Cinema".[90] The character of Dharumi was parodied in Iruttula Thedatheenga, a theatrical play performed in November 2013.[91] In a January 2015 interview with The Times of India, playwright Y. G. Mahendra said, "most character artists today lack variety [...] Show me one actor in India currently who can do a [Veerapandiya] Kattabomman, a VOC, a Vietnam Veedu, a Galatta Kalyanam and a Thiruvilayadal [sic]."[92] In October 2014, The Times of India ranked Thiruvilaiyadal fourth in its list, "Top 5 Sivaji Ganesan films on his birthday", appreciating the performances of Ganesan and Nagesh.[93]

Re-release

In mid-2012, legal issues arose when attempts were made to digitally re-release the film. G. Vijaya of Vijaya Pictures had filed a lawsuit against Gemini Colour Laboratory and Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures for attempting to re-release the film without her production company's permission. The reason for the suit was that in December 1975, Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures had transferred the entire rights of the film to Movie Film Circuit, which in turn had transferred them to Vijaya Pictures on 18 May 1976.[94] Vijaya Pictures approached the Gemini Colour Laboratory to digitise the film for re-release, however Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures asked laboratory officials not to release the film without their prior consent. Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures also disputed Vijaya's claim by running an advertisement in a Tamil newspaper on 18 May 2012, stating that it was the owner of the film's rights and anybody who wished to exhibit it in digital format should only do so with their permission. R. Subbiah, the judge who presided over the case, ordered the status quo to be maintained by both parties.[94][95]

Bolstered by the success of the re-release of Karnan (1964), Nagarajan's son and present head of Sri Vijayalakshmi Pictures, C. N. Paramasivam, found film negatives of Thiruvilayadal in a storage facility at Gemini Films. Paramasivam restored the film and re-released it in September 2012 in CinemaScope format.[3][14] The digitised version had its premiere at the Woodlands Theater in Royapettah, Chennai.[96][97] Despite being a re-release, the film earned public acclaim and was a commercial success.[98][99] Of the digitised version, Ganesan's son, producer Ramkumar said, "It was like watching a new film".[100]

Notes

- ↑ A Silver Jubilee is a celebration held to mark a 25th anniversary.

- ↑ G. Dhananjayan does not mention the name of the Tamil film dubbed into Kannada ten years before Thiruvilaiyadal and why there was a ban.[52]

References

- 1 2 Dhananjayan 2011, p. 232.

- ↑ Ganesan & Narayanaswami 2007, p. 150.

- 1 2 Raghavan, Nikhil (5 September 2012). "Classic gets a new life". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Guy 1997, pp. 280-281.

- ↑ Dhananjayan 2011, p. 232; Dhananjayan 2014, p. 187.

- ↑ Thiagarajan 1965, p. xviii; Dhananjayan 2011, p. 232; Dhananjayan 2014, p. 187.

- ↑ David 1983, p. 40.

- ↑ Dhananjayan 2011, p. 232; Dhananjayan 2014, pp. 186-187.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dhananjayan 2014, p. 186.

- ↑ Kannan, Uma (27 June 2011). "Kollywood's make-up specialists of the 1960s". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Tilak, Sudha G. (22 May 2004). "Mother goddesses rule the telly". Tehelka. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ Guy 1997, p. 120.

- ↑ "தென்னகத்தின் இசைக்குயில் மறைந்தது; தமிழ் சினிமா முன்னோடிகள் தொடர்-19". Ananda Vikatan (in Tamil). 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- 1 2 "டிஜிட்டல் தொழில்நுட்பத்தில் 'திருவிளையாடல்' படம் மீண்டும் ரிலீஸ்" [Thiruvilayadal released again in digital technology]. Maalai Malar (in Tamil). 6 September 2015. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ A. P. Nagarajan (5 October 2010). Thiruvilayadal — Sivaji Ganesan, Savitri — Tamil Devotional Movie (Motion picture). India: Rajshri Media. Opening credits from 0:55 to 1:20.

- ↑ Dhananjayan 2011, p. 232; Dhananjayan 2014, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 5 V. Raman, Mohan (9 September 2012). "An interesting nugget". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "திருவிளையாடல், தில்லானா மோகனாம்பாள் படங்களை தயாரித்த ஏ.பி.நாகராஜன்" [A. P. Nagarajan, the man who created Thiruvilaiyadal and Thillana Mohanambal]. Maalai Malar (in Tamil). 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Krishnamachari, Suganthy (13 August 2010). "Of performing arts". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 "திருவிளையாடல் படத்தில் தருமியாக வாழ்ந்து காட்டிய நாகேஷ்" [Nagesh, the man who lived the role of Dharumi in Thiruvilaiyadal]. Maalai Malar (in Tamil). 10 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ V. Raman, Mohan (14 April 2012). "Master of mythological cinema". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- 1 2 Dhananjayan 2011, p. 233; Dhananjayan 2014, p. 187.

- ↑ "10 வேடத்தில் நடித்த முதல் நடிகர் பி.யு சின்னப்பா ! ( தமிழ்சினிமா முன்னோடிகள்-தொடர் 24)". Ananda Vikatan (in Tamil). 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ A. P. Nagarajan (1 February 2010). Paattum Naane Bhavamum Naane — Thiruvilayadal Song — Sivaji Ganesan, T.S. Baliah (Motion picture). India: Rajshri Media.

- ↑ Panikkar 2002, p. 44.

- 1 2 Bharathwaj, R. (5 December 2008). "A different beat". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Ganesan & Narayanaswami 2007, p. 158.

- ↑ A. P. Nagarajan (5 October 2010). Thiruvilayadal — Sivaji Ganesan, Savitri — Tamil Devotional Movie (Motion picture). India: Rajshri Media. Clip from 1:13:35 to 1:16:18.

- ↑ Rajya V. R. 2014, pp. 46-47.

- ↑ Narayan, Hari (31 October 2016). "A sequel to the surprise hit, Chaar Sahibzaade". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Thiruvilaiyadal Songs". Raaga.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- 1 2 A. P. Nagarajan (1 February 2010). Neela Selai Kattikonda — Thiruvilayadal — Savithri (Motion picture). India: Rajshri Media.

- 1 2 Suganth, M.; Amarnath, Karuna (23 January 2009). "Classic Pick: Thiruvilayadal". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Rajya V. R. 2014, p. 57.

- 1 2 "Did You Know?". The Times of India. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- 1 2 Mani, Charulatha (27 September 2013). "A Raga's Journey — The royal Durbar". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Mani, Charulatha (21 December 2012). "A Raga's Journey — Towering Todi". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Mani, Charulatha (21 December 2012). "A Raga's Journey — Mesmeric Maand". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Mani, Charulatha (28 March 2014). "A Raga's Journey — Soothing the senses". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Mani, Charulatha (8 June 2012). "A Raga's Journey — Dynamic Durbarikaanada". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Mani, Charulatha (2 September 2011). "A Raga's Journey — Sacred Shanmukhapriya". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Mani, Charulatha (17 August 2012). "A Raga's Journey — Devotional Kambhoji". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Mani, Charulatha (5 September 2011). "A Raga's Journey — Aspects of Abheri". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Mani, Charulatha (25 October 2013). "A Raga's Journey — Godly Gowrimanohari". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Mani, Charulatha (20 January 2012). "A Raga's Journey — The passionate appeal of Simhendramadhyamam". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Krupa, Lakshmi (24 March 2013). "From kutcheris to recording studios". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Kolappan, B. (31 October 2012). "Artiste Cheena Kutty no more". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Kavitha, S. S. (30 January 2013). "Vestiges of an old art". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- 1 2 Guy 1997, p. 121.

- 1 2 Baskaran, Mana (22 May 2015). "சமயம் வழியே சமூகம் கண்ட காவியம்! - திருவிளையாடல்" [The epic seen by the people! - Thiruvilaiyadal]. The Hindu (in Tamil). Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Ramesh, M. (25 May 2013). "Veteran playback singer TMS is no more". Business Line. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ Dheenadhayalan, Pa. (27 June 2015). "சாவித்ரி- 8. தென்றலும் புயலும்". Dinamani (in Tamil). Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ Jeevanathan, V.; Sivashankar, Nithya (28 May 2012). "The painter of banners". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dhananjayan 2014, p. 187.

- ↑ V. Raman, Mohan (17 January 2011). "Movie hall crosses a milestone". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "வெற்றிகரமான வெள்ளி விழா...." [A successful Silver Jubilee]. Dina Thanthi (in Tamil). 14 January 1966. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "40th National Film Awards" (PDF). Directorate of Film Festivals. 1993. p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ↑ "13th National Film Awards" (PDF). Directorate of Film Festivals. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Film News Anandan (8 August 2001). "Filmography Of Dr. Sivaji Ganesan (Part-2)". Dinakaran (in Tamil). Archived from the original on 22 November 2001. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "திருவிளையாடல்" [Thiruvilaiyadal]. Kalki (in Tamil). 22 August 1965. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- 1 2 Dhananjayan 2014, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ Raman, Mohan V. (23 August 2014). "100 years of laughter". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Rajya V. R. 2014, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Baskaran, S. Theodore (February 2009). "Tragic comedian". Frontline. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Baskaran, S. Theodore; Warrier, Shobha (23 July 2001). "'He was the ultimate star'". Rediff. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ J. Rao, Subha; Jeshi, K. (30 June 2013). "Laughter lines". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Reminiscing Manorama: Comedy Loses Its Aachi Forever". The New Indian Express. 11 October 2015. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- 1 2 Rangarajan, Malathi (29 June 2007). "Nostalgia re-visited". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Rangan, Baradwaj (29 April 2011). "Lights, Camera, Conversation... — A dinosaur roams again". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "ரஜினியின் 100-வது படம் 'ஸ்ரீராகவேந்திரர்': ஸ்டைல்களை ஒதுக்கி விட்டு, மகானாகவே வாழ்ந்து காட்டினார்" [Rajini's 100th film 'Sri Raghavendrar': Leaving Behind The Style, He Lives The Role]. Maalai Malar (in Tamil). 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Shankar, K. (director) (1989). Meenakshi Thiruvilaiyadal (motion picture). India: Lakshmi Ganapathy Combines.

- ↑ Ravi, Bhama Devi (1 February 2009). "Mirth Gains Immortality". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Dhanush in a dilemma!". Sify. 19 September 2005. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Rangarajan, Malathi (11 August 2012). "In the name of ...". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Kumar, S. R. Ashok (13 July 2007). "Filmmakers' favourites". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "10 Best Films of late Nagesh". Sify. 1 February 2009. Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ Iyer, Aruna V. (12 May 2012). "For the love of Sivaji". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ S. P. Muthuraman (director) (1981). Netrikkan (motion picture). India: Kavithalayaa Productions.

- ↑ Vikraman (director) (1996). Poove Unakkaga (motion picture). India: Super Good Films. Event occurs at 24:00.

- ↑ Venkatesh, A. (director) (1996). Mahaprabhu (motion picture). India: Sri Sai Theja Films. Event occurs at 30:36.

- ↑ Rao, Singeetam Srinivasa (director) (1998). Kaathala Kaathala (motion picture). India: Raaj Kamal Films International. Event occurs at 1:22:52.

- ↑ Vasu, P. (director) (2000). Vanna Thamizh Pattu (motion picture). India: Murugan Cine Arts. Event occurs at 2:03:14.

- ↑ Gajendran, T. P. (director) (2001). Middle Class Madhavan (motion picture). India: K. R. G. Movies International. Event occurs at 23:39.

- ↑ Anbazhagan, P. C. (director) (2000). Kamarasu (motion picture). India: Saanthi Vanaraja Movies. Event occurs at 46:50.

- ↑ Paramesh, Sakthi (director) (10 August 2012). Vanakkam Thalaiva Full Movie Part 05 (motion Picture). India: Raj Video Vision Tamil. Event occurs at 04:00.

- ↑ Ganeshan, Susi (director) (2009). Kanthaswamy (motion picture). India: Kalaipuli Films International. Event occurs at 26:07.

- ↑ Rajesh, M. (director) (2012). Oru Kal Oru Kannadi (motion picture). India: Red Giant Movies. Event occurs at 1:17:50.

- ↑ Rangan, Baradwaj (5 April 2014). "Oru Kanniyum Moonu Kalavaanikalum : Time passages". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Thiruvilayaadal". Lollu Sabha. Season 1. Chennai. 5 May 2002. Star Vijay.

- ↑ "Naveena Thiruvilayaadal". Lollu Sabha. Season 1. Chennai. 28 July 2002. Star Vijay.

- ↑ "Radhika's mega serial goes on air". The Times of India. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Srinivasan, Pavithra (18 April 2012). "Special: The A to Z of Tamil Cinema". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ Krishnamachari, Suganthy (28 November 2013). "On how greed corrupts". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Oscar-worthy performance by Sivaji: Y Gee Mahendra". The Times of India. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "Top 5 Sivaji Ganesan films on his birthday". The Times of India. 1 October 2014. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Status quo ordered on digitising Thiruvilaiyadal". The New Indian Express. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bid to re-release Sivaji classic ends up in court". The Times of India. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Vijayan, S. (October 2012). "சினிமாஸ்கோப் டிஜிட்டலில் திருவிளையாடல்" [Thiruvilaiyadal in CinemaScope]. Idhayakkani (in Tamil). Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Woodlands Cinemas — Contact Us". Woodlands Cinemas. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Old hall makes it a no show for Pasamalar fans". The Hindu. 30 August 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ ""திருவிளையாடல்" டிஜிட்டல் திரைக்காவிய மறுவெளியீட்டு விளம்பரம்" [Thiruvilaiyadal Re-release Poster]. Daily Thanthi. 21 September 2012. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Thiruvilayadal next". The Hindu. 2 September 2012. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

Bibliography

- David, C. R. W. (1983). Cinema as Medium of Communication in Tamil Nadu. Christian Literature Society.

- Dhananjayan, G. (2011). The Best of Tamil Cinema, 1931 to 2010: 1931 to 1976. Galatta Media.

- Dhananjayan, G. (2014). Pride of Tamil Cinema: 1931 to 2013. Blue Ocean Publishers. ISBN 978-93-84301-05-7.

- Ganesan, Sivaji; Narayanaswami, T. S. (2007). Autobiography of an Actor: Sivaji Ganesan, October 1928 – July 2001. Sivaji Prabhu Charities Trust.

- Guy, Randor (1997). Starlight, Starbright: The Early Tamil Cinema. Amra Publishers.

- Panikkar, K. N. (2002). Culture, Ideology, Hegemony: Intellectuals and Social Consciousness in Colonial India. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-039-6.

- Rajya V. R., Rashmi (2014). "Narrative Strategies and Communication of Values in Tamil Epic Tradition Films of A. P. Nagarajan". University of Madras. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2015.

- Thiagarajan, K. (1965). Meenakshi Temple, Madurai. Meenakshi Sundareswarar Temple Renovation Committee.

External links