History of slavery

The history of slavery spans nearly every culture, nationality, and religion and from ancient times to the present day. However the social, economic, and legal position of slaves was vastly different in different systems of slavery in different times and places.[1]

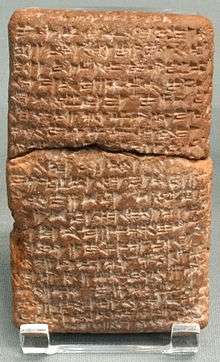

Slavery can be traced back to the earliest records, such as the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), which refers to it as an established institution.[2] Slavery is rare among hunter-gatherer populations, as it is developed as a system of social stratification. Slavery was known in civilizations as old as Sumer, as well as almost every other civilization. The Byzantine–Ottoman wars and the Ottoman wars in Europe resulted in the taking of large numbers of Christian slaves. Slavery became common within the British Isles during the Middle Ages. The Dutch and British played a prominent role in the Atlantic slave trade, especially after 1600. David P. Forsythe[3] wrote: "The fact remained that at the beginning of the nineteenth century an estimated three-quarters of all people alive were trapped in bondage against their will either in some form of slavery or serfdom."[4] Denmark-Norway was the first European country to ban the slave trade.

Although slavery is no longer legal anywhere in the world,[5] human trafficking remains an international problem and an estimated 25-40 million people are living in illegal slavery today.[6] During the 1983-2005 Second Sudanese Civil War people were taken into slavery.[7] Although Slavery in Mauritania was criminalized in August 2007,[8] in Mauritania it is estimated that up to 600,000 men, women and children, or 20% of the population, are currently enslaved, many of them used as bonded labor.[9] Evidence emerged in the late 1990s of systematic slavery in cacao plantations in West Africa; see the chocolate and slavery article.[10]

Origins

Evidence of slavery predates written records, and has existed in many cultures.[11] However, slavery is rare among hunter-gatherer populations. Mass slavery requires economic surpluses and a high population density to be viable. Due to these factors, the practice of slavery would have only proliferated after the invention of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution, about 11,000 years ago.[12]

Slavery was known in civilizations as old as Sumer, as well as in almost every other ancient civilization, including Ancient Egypt, Ancient China, the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, Ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, the Islamic Caliphate and Sultanate, and the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas.[13] Such institutions were a mixture of debt-slavery, punishment for crime, the enslavement of prisoners of war, child abandonment, and the birth of slave children to slaves.[14]

Africa

French historian Fernand Braudel noted that slavery was endemic in Africa and part of the structure of everyday life. "Slavery came in different guises in different societies: there were court slaves, slaves incorporated into princely armies, domestic and household slaves, slaves working on the land, in industry, as couriers and intermediaries, even as traders" (Braudel 1984 p. 435). During the 16th century, Europe began to outpace the Arab world in the export traffic, with its slave traffic from Africa to the Americas. The Dutch imported slaves from Asia into their colony in South Africa. In 1807 Britain, which held extensive, although mainly coastal, colonial territories on the African continent (including southern Africa), made the international slave trade illegal, as did the United States in 1808.

In Senegambia, between 1300 and 1900, close to one-third of the population was enslaved. In early Islamic states of the Western Sudan, including Ghana (750–1076), Mali (1235–1645), Segou (1712–1861), and Songhai (1275–1591), about a third of the population was enslaved. In Sierra Leone in the 19th century about half of the population consisted of slaves. In the 19th century at least half the population was enslaved among the Duala of the Cameroon, the Igbo and other peoples of the lower Niger, the Kongo, and the Kasanje kingdom and Chokwe of Angola. Among the Ashanti and Yoruba a third of the population consisted of slaves. The population of the Kanem was about a third slave. It was perhaps 40% in Bornu (1396–1893). Between 1750 and 1900 from one- to two-thirds of the entire population of the Fulani jihad states consisted of slaves. The population of the Sokoto caliphate formed by Hausas in northern Nigeria and Cameroon was half-slave in the 19th century. It is estimated that up to 90% of the population of Arab-Swahili Zanzibar was enslaved. Roughly half the population of Madagascar was enslaved.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

The Anti-Slavery Society estimated that there were 2,000,000 slaves in the early 1930s Ethiopia, out of an estimated population of between 8 and 16 million.[21] Slavery continued in Ethiopia until the brief Second Italo-Abyssinian War in October 1935, when it was abolished by order of the Italian occupying forces.[22] In response to pressure by Western Allies of World War II Ethiopia officially abolished slavery and serfdom after regaining its independence in 1942. On 26 August 1942 Haile Selassie issued a proclamation outlawing slavery.[23][24]

When British rule was first imposed on the Sokoto Caliphate and the surrounding areas in northern Nigeria at the turn of the 20th century, approximately 2 million to 2.5 million people there were slaves.[25] Slavery in northern Nigeria was finally outlawed in 1936.[26]

Elikia M'bokolo, April 1998, Le Monde diplomatique. Quote: "The African continent was bled of its human resources via all possible routes. Across the Sahara, through the Red Sea, from the Indian Ocean ports and across the Atlantic. At least ten centuries of slavery for the benefit of the Muslim countries (from the ninth to the nineteenth)." He continues: "Four million slaves exported via the Red Sea, another four million through the Swahili ports of the Indian Ocean, perhaps as many as nine million along the trans-Saharan caravan route, and eleven to twenty million (depending on the author) across the Atlantic Ocean"[27]

Sub-Saharan Africa

David Livingstone wrote of the slave trades:

To overdraw its evils is a simple impossibility.... We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path. [Onlookers] said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer. We passed a woman tied by the neck to a tree and dead.... We came upon a man dead from starvation.... The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems really to be broken heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves.

Livingstone estimated that 80,000 Africans died each year before ever reaching the slave markets of Zanzibar.[28][29][30][31] Zanzibar was once East Africa's main slave-trading port, and under Omani Arabs in the 19th century as many as 50,000 slaves were passing through the city each year.[32]

Prior to the 16th century, the bulk of slaves exported from Africa were shipped from East Africa to the Arabian peninsula. Zanzibar became a leading port in this trade. Arab slave traders differed from European ones in that they would often conduct raiding expeditions themselves, sometimes penetrating deep into the continent. They also differed in that their market greatly preferred the purchase of female slaves over male ones.

The increased presence of European rivals along the East coast led Arab traders to concentrate on the overland slave caravan routes across the Sahara from the Sahel to North Africa. The German explorer Gustav Nachtigal reported seeing slave caravans departing from Kukawa in Bornu bound for Tripoli and Egypt in 1870. The slave trade represented the major source of revenue for the state of Bornu as late as 1898. The eastern regions of the Central African Republic have never recovered demographically from the impact of 19th-century raids from the Sudan and still have a population density of less than 1 person/km².[33] During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces. Mahdi's victory created an Islamic state, one that quickly reinstituted slavery.[34][35]

The Middle Passage, the crossing of the Atlantic to the Americas, endured by slaves laid out in rows in the holds of ships, was only one element of the well-known triangular trade engaged in by Portuguese, Dutch, French and British. Ships having landed slaves in Caribbean ports would take on sugar, indigo, raw cotton, and later coffee, and make for Liverpool, Nantes, Lisbon or Amsterdam. Ships leaving European ports for West Africa would carry printed cotton textiles, some originally from India, copper utensils and bangles, pewter plates and pots, iron bars more valued than gold, hats, trinkets, gunpowder and firearms and alcohol. Tropical shipworms were eliminated in the cold Atlantic waters, and at each unloading, a profit was made.

The Atlantic slave trade peaked in the late 18th century, when the largest number of slaves were captured on raiding expeditions into the interior of West Africa. These expeditions were typically carried out by African states, such as the Oyo empire (Yoruba), Kong Empire, Kingdom of Benin, Imamate of Futa Jallon, Imamate of Futa Toro, Kingdom of Koya, Kingdom of Khasso, Kingdom of Kaabu, Fante Confederacy, Ashanti Confederacy, Aro Confederacy and the kingdom of Dahomey.[36] Europeans rarely entered the interior of Africa, due to fear of disease and moreover fierce African resistance. The slaves were brought to coastal outposts where they were traded for goods. The people captured on these expeditions were shipped by European traders to the colonies of the New World. As a result of the War of the Spanish Succession, the United Kingdom obtained the monopoly (asiento de negros) of transporting captive Africans to Spanish America. It is estimated that over the centuries, twelve to twenty million people were shipped as slaves from Africa by European traders, of whom some 15 percent died during the terrible voyage, many during the arduous journey through the Middle Passage. The great majority were shipped to the Americas, but some also went to Europe and Southern Africa.

North Africa

In Algiers during the time of the Regency of Algiers in North Africa in the 19th century, 1.5 million Christians and Europeans were captured and forced into slavery. This eventually led to the Bombardment of Algiers in 1816.[37]

African participation in the slave trade

African states played a key role in the slave trade. Slavery was a common practice among Africans. There were three types: those who were slaves through conquest, those who were slaves due to unpaid debts or those whose parents gave them as slaves to tribal chiefs. Chieftains would barter their slaves to European buyers for rum, spices, cloth or other goods.[38] Selling captives or prisoners was common practice among Africans and Arabs during that era. However, as the Atlantic slave trade increased its demand, local systems which primarily serviced indentured servitude expanded and started to supply the European slave traders, changing social dynamics. It also ultimately undermined local economies and political stability as villages' vital labor forces were shipped overseas as slave raids and civil wars became commonplace. Crimes which were previously punishable by some other means became punishable by enslavement.[39]

The prisoners and captives that were sold were usually from neighboring or enemy ethnic groups.[40] These captive slaves were not considered as part of the ethnic group or 'tribe' and kings did not have a particular loyalty to them. At times, kings and chiefs would sell criminals into slavery so that they could no longer commit crimes in that area. Most other slaves were obtained from kidnappings, or through raids that occurred at gunpoint working together with Europeans.[38] Some African kings refused to sell any of their captives or criminals. King Jaja of Opobo, a former slave himself, completely refused to do business with slavers.[40] Ashanti King Agyeman Prempeh (Ashanti king, b. 1872) also sacrificed his own freedom so that his people would not face collective slavery.[40]

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, slavery had already existed in Kingdom of Kongo. Despite its establishment within his kingdom, Afonso I of Kongo believed that the slave trade should be subject to Kongo law. When he suspected the Portuguese of receiving illegally enslaved persons to sell, he wrote letters to the King João III of Portugal in 1526 imploring him to put a stop to the practice.[41]

The kings of Dahomey sold their war captives into transatlantic slavery, who otherwise would have been killed in a ceremony known as the Annual Customs. As one of West Africa's principal slave states, Dahomey became extremely unpopular with neighbouring peoples.[42][43][44] Like the Bambara Empire to the east, the Khasso kingdoms depended heavily on the slave trade for their economy. A family's status was indicated by the number of slaves it owned, leading to wars for the sole purpose of taking more captives. This trade led the Khasso into increasing contact with the European settlements of Africa's west coast, particularly the French.[45] Benin grew increasingly rich during the 16th and 17th centuries on the slave trade with Europe; slaves from enemy states of the interior were sold, and carried to the Americas in Dutch and Portuguese ships. The Bight of Benin's shore soon came to be known as the "Slave Coast".[46]

In the 1840s, King Gezo of Dahomey said:[10][47]

The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth…the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery…

In 1807, Britain made illegal the international trade in slaves. The King of Bonny (now in Nigeria) was horrified at the conclusion of the practice:[48]

We think this trade must go on. That is the verdict of our oracle and the priests. They say that your country, however great, can never stop a trade ordained by God himself.

Joseph Miller states that African buyers would prefer males, but in reality women and children would be easily captured as men fled. Those captured would be sold for various reasons such as food, debts, or servitude. Once captured, the journey to the coast killed many and weakened others. Disease engulfed many, and insufficient food damaged those who made it to the coasts. Scurvy was so common that it was known as mal de Luanda (Luanda sickness. [49] The assumption for those who died on the journey died from malnutrition. As food was limited, water may have been just as worse. Dysentery was widespread and poor sanitary conditions at ports did not help. Since supplies were poor, slaves were not equipped with the best clothing that further exposed to more diseases. [50]

If the fear of disease caused terror, the psyche of slaves for being captured was just as terrifying. The most popular assumption for being captured was Europeans were cannibals. Stories and rumors spread around that whites captured Africans to eat them. [51] ). Olaudah Equiano accounts his experience about the sorrow slaves encountered at the ports. He talks about him first moment on a slave ship and asked if he was going to be eaten. [52] Yet, the worst for slaves has only begun, and the journey on the water proved to be more terrifying. It would be important to realize that for every 100 Africans captured, 64 would reach the coast, and about 50 would reach the New World. [53]

Others believe that slavers had a vested interest in capturing rather than killing, and in keeping their captives alive; and that this coupled with the disproportionate removal of males and the introduction of new crops from the Americas (cassava, maize) would have limited general population decline to particular regions of western Africa around 1760–1810, and in Mozambique and neighbouring areas half a century later. There has also been speculation that within Africa, females were most often captured as brides, with their male protectors being a "bycatch" who would have been killed if there had not been an export market for them.

Scottish explorer Mungo Park encountered a group of slaves when traveling through Mandinka country:

They were all very inquisitive, but they viewed me at first with looks of horror, and repeatedly asked if my countrymen were cannibals. They were very desirous to know what became of the slaves after they had crossed the salt water. I told them that they were employed in cultivation the land; but they would not believe me ... A deeply-rooted idea that the whites purchase negroes for the purpose of devouring them, or of selling them to others that they may be devoured hereafter, naturally makes the slaves contemplate a journey towards the coast with great terror, insomuch that the slatees are forced to keep them constantly in irons, and watch them very closely, to prevent their escape.[54]

During the period from late 19th century and early 20th century, demand for the labor-intensive harvesting of rubber drove frontier expansion and forced labor. The personal monarchy of Belgian King Leopold II in the Congo Free State saw mass killings and slavery to extract rubber.[55]

Africans on ships

Stephanie Smallwood in her book Saltwater Slavery uses Equiano’s account on board ships to describe the general thoughts of most slaves.

Then,” said I, “how comes it in all our country we never heard of them?” They told me because they lived so very far off. I then asked where were their women? Had they any like themselves? I was told that they had. “And why,” said I, “do we not see them?” They answered, because they were left behind. I asked how the vessel could go? They told me they could not tell; but that there was cloth put upon the masts by the help of the ropes I saw, and then the vessel went on; and the white men had some spell or magic they put in the water when they liked, in order to stop the vessel. I was exceedingly amazed at this account, and really thought they were spirits. I there-fore wished much to be from amongst them, for I expected they would sacrifice me; but my wishes were vain—for we were so quartered that it was impossible for any of us to make our escape.

Accounts like these raised many questions as some slaves grew philosophical with their journey. Smallwood points the challenges for slaves were physical and metaphysical. The physical would be obvious as the challenge to overcome capacity, lack of ship room, and food. The metaphysical was unique as the open sea would challenge African slaves vision of the ocean as habitable. [57] At essence, the journey on the ocean would prove to be African’s biggest fear that would keep them in awe. Combine this with the lack of knowledge of the sea, Africans would be entering a world of anxiety never seen before. Yet, Europeans were also fearful of the sea, but not to the extent of Africans. One of these dilemma comes with the sense of time. Africans used seasonal weather to predict time and days. The moon was a sense of time, but used like in other cultures. On sea, Africans used the moon to best count the days, but the sea did not provide seasonal changes for them to know how long they were at sea. [58] Counting the days on a ship was the not main priority however. Surviving the voyage was one of the many horrors. No one escaped diseases as the close quarters infected everyone even the crew. Death was common that ships were called tumbeiros or floating tombs. [59] What shocked Africans the most was how death was handled in the ships. Smallwood says the traditions for an African death was delicate and community based. On ships, bodies would be thrown into the sea. Because the sea represented bad omens, bodies in the sea represented a form of purgatory and the ship a form of hell. In the end, the Africans who made the journey would have survived disease, malnutrition, confined space, close death, and the trauma of the ship.

Modern times

The trading of children has been reported in modern Nigeria and Benin. In parts of Ghana, a family may be punished for an offense by having to turn over a virgin female to serve as a sex slave within the offended family. In this instance, the woman does not gain the title or status of "wife". In parts of Ghana, Togo, and Benin, shrine slavery persists, despite being illegal in Ghana since 1998. In this system of ritual servitude, sometimes called trokosi (in Ghana) or voodoosi in Togo and Benin, young virgin girls are given as slaves to traditional shrines and are used sexually by the priests in addition to providing free labor for the shrine.

During the Second Sudanese Civil War people were taken into slavery; estimates of abductions range from 14,000 to 200,000. Abduction of Dinka women and children was common.[7] In Mauritania it is estimated that up to 600,000 men, women and children, or 20% of the population, are currently enslaved, many of them used as bonded labor.[9] Slavery in Mauritania was criminalized in August 2007.[8]

Evidence emerged in the late 1990s of systematic slavery in cacao plantations in West Africa; see the chocolate and slavery article.[10]

The Americas

Among indigenous peoples

In Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica the most common forms of slavery were those of prisoners of war and debtors. People unable to pay back debts could be sentenced to work as slaves to the persons owed until the debts were worked off. Warfare was important to Maya society, because raids on surrounding areas provided the victims required for human sacrifice, as well as slaves for the construction of temples.[60] Most victims of human sacrifice were prisoners of war or slaves.[61] According to Aztec writings, as many as 84,000 people were sacrificed at a temple inauguration in 1487.[62] Slavery was not usually hereditary; children of slaves were born free. In the Inca Empire, workers were subject to a mita in lieu of taxes which they paid by working for the government. Each ayllu, or extended family, would decide which family member to send to do the work. It is unclear if this labor draft or corvée counts as slavery. The Spanish adopted this system, particularly for their silver mines in Bolivia.[63]

Other slave-owning societies and tribes of the New World were, for example, the Tehuelche of Patagonia, the Comanche of Texas, the Caribs of Dominica, the Tupinambá of Brazil, the fishing societies, such as the Yurok, that lived along the coast from what is now Alaska to California, the Pawnee and Klamath.[64] Many of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, such as the Haida and Tlingit, were traditionally known as fierce warriors and slave-traders, raiding as far as California. Slavery was hereditary, the slaves being prisoners of war. Among some Pacific Northwest tribes about a quarter of the population were slaves.[65][66] One slave narrative was composed by an Englishman, John R. Jewitt, who had been taken alive when his ship was captured in 1802; his memoir provides a detailed look at life as a slave, and asserts that a large number were held.

Spanish America

During the period from late 19th century and early 20th century, demand for the labor-intensive harvesting of rubber drove frontier expansion and slavery in Latin America and elsewhere. Indigenous peoples were enslaved as part of the rubber boom in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Brazil.[67] In Central America, rubber tappers participated in the enslavement of the indigenous Guatuso-Maleku people for domestic service.[68]

Brazil

Slavery was a mainstay of the Brazilian colonial economy, especially in mining and sugarcane production.[69] 35.3% of all slaves involved in the Atlantic Slave trade went to Brazil. 4 million slaves were obtained by Brazil, 1.5 million more than any other country.[70] Starting around 1550, the Portuguese began to trade African slaves to work the sugar plantations, once the native Tupi people deteriorated. Although Portuguese Prime Minister Marquês de Pombal abolished slavery in mainland Portugal on 12 February 1761, slavery continued in her overseas colonies. Slavery was practiced among all classes. Slaves were owned by upper and middle classes, by the poor, and even by other slaves.[71]

From São Paulo, the Bandeirantes, adventurers mostly of mixed Portuguese and native ancestry, penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Along the Amazon river and its major tributaries, repeated slaving raids and punitive attacks left their mark. One French traveler in the 1740s described hundreds of miles of river banks with no sign of human life and once-thriving villages that were devastated and empty. In some areas of the Amazon Basin, and particularly among the Guarani of southern Brazil and Paraguay, the Jesuits had organized their Jesuit Reductions along military lines to fight the slavers. In the mid-to-late 19th century, many Amerindians were enslaved to work on rubber plantations.[72][73][74]

Resistance and abolition

Escaped slaves formed Maroon communities which played an important role in the histories of Brazil and other countries such as Suriname, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Jamaica. In Brazil, the Maroon villages were called palenques or quilombos. Maroons survived by growing vegetables and hunting. They also raided plantations. At these attacks, the maroons would burn crops, steal livestock and tools, kill slavemasters, and invite other slaves to join their communities.[75]

Jean-Baptiste Debret, a French painter who was active in Brazil in the first decades of the 19th century, started out with painting portraits of members of the Brazilian Imperial family, but soon became concerned with the slavery of both blacks and indigenous inhabitants. His paintings on the subject (two appear on this page) helped bring attention to the subject in both Europe and Brazil itself.

The Clapham Sect, a group of evangelical reformers, campaigned during much of the 19th century for Britain to use its influence and power to stop the traffic of slaves to Brazil. Besides moral qualms, the low cost of slave-produced Brazilian sugar meant that British colonies in the West Indies were unable to match the market prices of Brazilian sugar, and each Briton was consuming 16 pounds (7 kg) of sugar a year by the 19th century. This combination led to intensive pressure from the British government for Brazil to end this practice, which it did by steps over several decades.[76]

First, foreign slave trade was banned in 1850. Then, in 1871, the sons of the slaves were freed. In 1885, slaves aged over 60 years were freed. The Paraguayan War contributed to ending slavery, since many slaves enlisted in exchange for freedom. In Colonial Brazil, slavery was more a social than a racial condition. Some of the greatest figures of the time, like the writer Machado de Assis and the engineer André Rebouças had black ancestry.

Brazil's 1877–78 Grande Seca (Great Drought) in the cotton-growing northeast led to major turmoil, starvation, poverty and internal migration. As wealthy plantation holders rushed to sell their slaves south, popular resistance and resentment grew, inspiring numerous emancipation societies. They succeeded in banning slavery altogether in the province of Ceará by 1884.[77] Slavery was legally ended nationwide on 13 May by the Lei Áurea ("Golden Law") of 1888. It was an institution in decadence at these times, as since the 1880s the country had begun to use European immigrant labor instead. Brazil was the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery.[78]

British and French Caribbean

Slavery was commonly used in the parts of the Caribbean controlled by France and the British Empire. The Lesser Antilles islands of Barbados, St. Kitts, Antigua, Martinique and Guadeloupe, which were the first important slave societies of the Caribbean, began the widespread use of African slaves by the end of the 17th century, as their economies converted from sugar production.[79]

By 1778, the French were importing approximately 13,000 Africans for enslavement yearly to the French West Indies.[80]

To regularise slavery, in 1685 Louis XIV had enacted the code noir, which accorded certain human rights to slaves and responsibilities to the master, who was obliged to feed, clothe and provide for the general well-being of his slaves. Free blacks owned one-third of the plantation property and one-quarter of the slaves in Saint Domingue (later Haiti).[81] Slavery in the French Republic was abolished on 4 February 1794. When it became clear that Napoleon intended to re-establish slavery in Haiti, Dessalines and Pétion switched sides, in October 1802. On 1 January 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the new leader under the dictatorial 1801 constitution, declared Haiti a free republic.[82] Thus Haiti became the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere, after the United States, and the only successful slave rebellion in world history.[83]

Whitehall in England announced in 1833 that slaves in its territories would be totally freed by 1840. In the meantime, the government told slaves they had to remain on their plantations and would have the status of "apprentices" for the next six years.

In Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, on 1 August 1834, an unarmed group of mainly elderly Negroes being addressed by the Governor at Government House about the new laws, began chanting: "Pas de six ans. Point de six ans" ("Not six years. No six years"), drowning out the voice of the Governor. Peaceful protests continued until a resolution to abolish apprenticeship was passed and de facto freedom was achieved. Full emancipation for all was legally granted ahead of schedule on 1 August 1838, making Trinidad the first British colony with slaves to completely abolish slavery.[84]

After Great Britain abolished slavery, it began to pressure other nations to do the same. France, too, abolished slavery. By then Saint-Domingue had already won its independence and formed the independent Republic of Haiti. French-controlled islands were then limited to a few smaller islands in the Lesser Antilles.

Anglo North America

Early events

In 1619 twenty Africans were brought to the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia. Historians are undecided if the legal practice of slavery began there, since at least some of them had the status of indentured servant. Alden T. Vaughn says most agree that both Negro slaves and indentured servants existed by 1640.[85]

Only a fraction of the enslaved Africans brought to the New World came to British North America, perhaps as little as 5% of the total. The vast majority of slaves were sent to the Caribbean sugar colonies, Brazil, or Spanish America.

By the 1680s, with the consolidation of England's Royal African Company, enslaved Africans were arriving in English colonies in larger numbers, and the institution continued to be protected by the British government. Colonists now began purchasing slaves in larger numbers.

Slavery in American colonial law

- 1640: Virginia courts sentence John Punch to lifetime slavery, marking the earliest legal sanctioning of slavery in English colonies.[86]

- 1641: Massachusetts legalizes slavery.[87]

- 1650: Connecticut legalizes slavery.

- 1654: Virginia sanctions "the right of Negros to own slaves of their own race" after African Anthony Johnson, former indentured servant, sued to have fellow African John Casor declared not an indentured servant but "slave for life."[88]

- 1661: Virginia officially recognizes slavery by statute.

- 1662: A Virginia statute declares that children born would have the same status as their mother.

- 1663: Maryland legalizes slavery.

- 1664: Slavery is legalized in New York and New Jersey.[89]

- 1670: Carolina (later, South Carolina and North Carolina) is founded mainly by planters from the overpopulated British sugar island colony of Barbados, who brought relatively large numbers of African slaves from that island.[90]

Development of slavery

The shift from indentured servants to African slaves was prompted by a dwindling class of former servants who had worked through the terms of their indentures and thus became competitors to their former masters. These newly freed servants were rarely able to support themselves comfortably, and the tobacco industry was increasingly dominated by large planters. This caused domestic unrest culminating in Bacon's Rebellion. Eventually, chattel slavery became the norm in regions dominated by plantations.

The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina established a model in which a rigid social hierarchy placed slaves under the absolute authority of their master. With the rise of a plantation economy in the Carolina Lowcountry based on rice cultivation a slave society was created that later became the model for the King Cotton economy across the Deep South. The model created by South Carolina was driven by the emergence of a majority slave population that required repressive and often brutal force to control. Justification for such a slave society developed into a conceptual framework of white superiority and aristocratic privilege.[91]

Several local slave rebellions took place during the 17th and 18th centuries: Gloucester County, Virginia Revolt (1663);[92] New York Slave Revolt of 1712; Stono Rebellion (1739); and New York Slave Insurrection of 1741.[93]

Early United States law

The Republic of Vermont banned slavery in its constitution of 1777 and continued the ban when it entered the United States in 1791.[94] Through the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 under the Congress of the Confederation, slavery was prohibited in the territories north west of the Ohio River. By 1804, abolitionists succeeded in passing legislation that ended legal slavery in every northern state (with slaves above a certain age legally transformed to indentured servants).[95] Congress banned the international importation or export of slaves on 1 January 1808; but not the internal slave trade.[96]

Despite the actions of abolitionists, free blacks were subject to racial segregation in the Northern states.[97] Slavery was legal in most of Canada until 1833, but after that it offered a haven for hundreds of runaway slaves. Refugees from slavery fled the South across the Ohio River to the North via the Underground Railroad. Midwestern state governments asserted States Rights arguments to refuse federal jurisdiction over fugitives. Some juries exercised their right of jury nullification and refused to convict those indicted under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

After the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854, armed conflict broke out in Kansas Territory, where the question of whether it would be admitted to the Union as a slave state or a free state had been left to the inhabitants. The radical abolitionist John Brown was active in the mayhem and killing in "Bleeding Kansas." The true turning point in public opinion is better fixed at the Lecompton Constitution fraud. Pro-slavery elements in Kansas had arrived first from Missouri and quickly organized a territorial government that excluded abolitionists. Through the machinery of the territory and violence, the pro-slavery faction attempted to force an unpopular pro-slavery constitution through the state. This infuriated Northern Democrats, who supported popular sovereignty, and was exacerbated by the Buchanan administration reneging on a promise to submit the constitution to a referendum—which would surely fail. Anti-slavery legislators took office under the banner of the newly formed Republican Party. The Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision of 1857 asserted that one could take one's property anywhere, even if one's property was chattel and one crossed into a free territory. It also asserted that African Americans could not be federal citizens. Outraged critics across the North denounced these episodes as the latest of the Slave Power (the politically organized slave owners) taking more control of the nation.[98]

Civil War

The slave population in the United States stood at four million.[99] 95% of blacks lived in the South, comprising one third of the population there as opposed to 1% of the population of the North. The central issue in politics in the 1850s involved rich Southern slaveowners moving into the western territories, bringing their slaves, and buying the best lands to the detriment of the average white farmers. The Whig Party split and collapsed on the slavery issue, to be replaced in the North by the new Republican Party, which was dedicated to stopping the expansion of slavery. Republicans gained a majority in every northern state by absorbing a faction of anti-slavery Democrats, and warning that slavery was a backward system that undercut democracy and economic modernization.[100] Numerous compromise proposals were put forward, but they all collapsed. Basically a majority of Northern voters were committed to stopping the expansion of slavery, which they believed would ultimately end slavery. Southern voters were overwhelmingly angry that they were being treated as second-class citizens. In the election of 1860, the Republicans swept Abraham Lincoln into the Presidency and his party took control (with only 39.8% of the popular vote) and legislators into Congress. The states of the deep South, convinced that the economic power of what they called "King Cotton" would overwhelm the North and win support from Europe voted to seceded from the U.S. (the Union). They formed the Confederate States of America, based on the promise of maintaining slavery. War broke out in April 1861, as both sides sought wave after wave of enthusiasm among young men volunteering to form new regiments and new armies. In the North, the main goal was to preserve the union as an expression of American nationalism.

By 1862 most northern leaders realized that the mainstay of Southern secession, slavery, had to be attacked head-on. All the border states rejected President Lincoln's proposal for compensated emancipation. However, by 1865 all had begun the abolition of slavery, except Kentucky and Delaware. The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by Lincoln on 1 January 1863. In a single stroke it changed the legal status, as recognized by the U.S. government, of 3 million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free." It had the practical effect that as soon as a slave escaped the control of the Confederate government, by running away or through advances of federal troops, the slave became legally and actually free. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible out of reach of the Union army. By June 1865, the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all of the designated slaves. The owners were never compensated.[101] Over 200,000 free blacks and newly freed slaves fought for the Union in the Army and Navy, thereby validating their claims to full citizenship.[102]

The severe dislocations of war and Reconstruction had a severe negative impact on the black population, with a large amount of sickness and death.[103][104] After liberation, many of the Freedmen remained on the same plantation. Others fled or crowded into refugee camps operated by the Freedmen's Bureau. The Bureau provided food, housing, clothing, medical care, church services, some schooling, legal support, and arranged for labor contracts.[105] Fierce debates about the rights of the Freedmen, and of the defeated Confederates, often accompanied by killings of black leaders, marked the Reconstruction Era, 1863–77.[106]

Slavery was never reestablished, but after 1877, white Democrats took control of all the southern states and blacks lost nearly all the political power they had achieved during Reconstruction. By 1900 they also lost the right to vote. They had become second class citizens. The great majority lived in the rural South in poverty working as laborers, sharecroppers or tenant farmers; a small proportion owned their own land. The black churches, especially the Baptist Church, was the center of community activity and leadership.[107]

Asia

Slavery has existed all throughout Asia, and forms of slavery still exist today.

Classic era

Ancient India

Scholars differ as to whether or not slaves and the institution of slavery existed in ancient India. These English words have no direct, universally accepted equivalent in Sanskrit or other Indian languages, but some scholars translate the word dasa, mentioned in texts like Manu Smriti.,[108] as slaves.[109] Ancient historians who visited India offer the closest linguistic equivalence in Indian society and slavery in other ancient civilizations. For example, the Greek historian Arrian, who chronicled India about the time of Alexander the Great, wrote in his Indika,[110]

The Indians do not even use aliens as slaves, much less a countryman of their own.— The Indika of Arrian[110]

Ancient China

- Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) Men sentenced to castration became eunuch slaves of the Qin dynasty state to do forced labor, for projects like the Terracotta Army.[111] The Qin government confiscated the property and enslaved the families of those who received castration as a punishment for rape.[112]

- Slaves were deprived of their rights and connections to their families.[113]

- Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) One of Emperor Gao's first acts was to set free from slavery agricultural workers enslaved during the Warring States period, although domestic servants retained their status.

- Men punished with castration during the Han dynasty were also used as slave labor.[114]

- Deriving from earlier Legalist laws, the Han dynasty set in place rules that the property of and families of criminals doing three years of hard labor or sentenced to castration were to have their families seized and kept as property by the government.[115]

Middle Ages

India

The Islamic invasions, starting in 8th century, also resulted in hundreds of thousands of Indians being enslaved by the invading armies.[116][117][118][119] Qutb-ud-din Aybak, a Turkic slave of Muhammad Ghori rose to power following his master's death. For almost a century, his descendants ruled North-Central India in form of Slave Dynasty. Several slaves were also brought to India by the Indian Ocean trades; for example, the Siddi are descendants of Bantu slaves brought to India by Arab and Portuguese merchants.[120] Slavery was officially abolished in British India by the Indian Slavery Act V. of 1843. However, in modern India, Pakistan and Nepal, there are millions of bonded laborers, who work as slaves to pay off debts.[121][122][123]

China

During the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD), Chinese captured Korean civilians from Koguryo, Paekche, and Silla to sell as slaves.[124][125] Slavery was prevalent until the late 19th century and early 20th century China.[126] All forms of slavery have been illegal in China since 1910.[127]

Modern era

Japan

Slavery in Japan was, for most of its history, indigenous, since the export and import of slaves was restricted by Japan being a group of islands. In late-16th-century Japan, slavery was officially banned; but forms of contract and indentured labor persisted alongside the period penal codes' forced labor. During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War, the Japanese military used millions of civilians and prisoners of war from several countries as forced laborers.[128][129][130]

Korea

In Korea, slavery was officially abolished with the Gabo Reform of 1894 under Japanese pressure to eliminate slavery. However, during poor harvests and famine, many peasants would voluntarily sell themselves into slavery in order to survive.[131][132][133]

South-East Asia

In South-East Asia, there was a large slave class in Khmer Empire who built the enduring monuments in Angkor Wat and did most of the heavy work.[134] Between the 17th and the early 20th centuries one-quarter to one-third of the population of some areas of Thailand and Burma were slaves.[135] There are currently an estimated 300,000 women and children involved in the sex slave trade throughout Southeast Asia.[136] According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), an estimated 800,000 people are subject to forced labor in Myanmar.[137]

Slavery in pre-Spanish Philippines was practiced by the tribal Austronesian peoples who inhabited the culturally diverse islands. The neighbouring Muslim states conducted slave raids from the 1600s into the 1800s in coastal areas of the Gulf of Thailand and the Philippine islands.[138][139] Slaves in Toraja society in Indonesia were family property. People would become slaves when they incurred a debt. Slaves could also be taken during wars, and slave trading was common. Torajan slaves were sold and shipped out to Java and Siam. Slaves could buy their freedom, but their children still inherited slave status. Slavery was abolished in 1863 in all Dutch colonies.[140][141]

Europe

Classic era

Ancient Greece

Records of slavery in Ancient Greece go as far back as Mycenaean Greece. The origins are not known, but it appears that slavery became an important part of the economy and society only after the establishment of cities.[142] Slavery was common practice and an integral component of ancient Greece, as it was in other societies of the time, including ancient Israel and early Christian societies.[143][144][145] It is estimated that in Athens, the majority of citizens owned at least one slave. Most ancient writers considered slavery not only natural but necessary, but some isolated debate began to appear, notably in Socratic dialogues. The Stoics produced the first condemnation of slavery recorded in history.[145]

During the 8th and the 7th centuries BC, in the course of the two Messenian Wars, the Spartans reduced an entire population to a pseudo-slavery called helotry.[146] According to Herodotus (IX, 28–29), helots were seven times as numerous as Spartans. Following several helot revolts around the year 600 BC, the Spartans restructured their city-state along authoritarian lines, for the leaders decided that only by turning their society into an armed camp could they hope to maintain control over the numerically dominant helot population.[147] In some Ancient Greek city states about 30% of the population consisted of slaves, but paid and slave labor seem to have been equally important.[148]

Rome

Romans inherited the institution of slavery from the Greeks and the Phoenicians.[149] As the Roman Republic expanded outward, it enslaved entire populations, thus ensuring an ample supply of laborers to work in Rome's farms and households. The people subjected to Roman slavery came from all over Europe and the Mediterranean. Such oppression by an elite minority eventually led to slave revolts; the Third Servile War led by Spartacus was the most famous and severe. Greeks, Berbers, Germans, Britons, Slavs, Thracians, Gauls (or Celts), Jews, Arabs and many more ethnic groups were enslaved to be used for labor, and also for amusement (e.g. gladiators and sex slaves). If a slave ran away, they were liable to be crucified.

The overall impact of slavery on the Italian genetics was insignificant though, because the slaves imported in Italy were native Europeans, and very few if any of them had extra European origin. This has been further confirmed by recent biochemical analysis of 166 skeletons from three non-elite imperial-era cemeteries in the vicinity of Rome (where the bulk of the slaves lived), which shows that only 1 individual definitely came from outside of Europe (North Africa), and another 2 possibly did, but results are inconclusive. In the rest of the Italian peninsula, the amount of non European slaves was definitively much lower than that.[150][151]

Celtic tribes

Celtic tribes of Europe are recorded by various Roman sources as owning slaves. The extent of slavery in prehistorical Europe is not well known, however.[152]

According to Calgacus's speech to his troops fighting the Roman Empire in 85 AD, as recorded by Tacitus, his speech said that the British Isles did not have slavery.[153]

Middle Ages

The chaos of invasion and frequent warfare also resulted in victorious parties taking slaves throughout Europe in the early Middle Ages. St. Patrick, himself captured and sold as a slave, protested against an attack that enslaved newly baptized Christians in his "Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus". As a commonly traded commodity, like cattle, slaves could become a form of internal or trans-border currency.[154] Slavery during the Early Middle Ages had several distinct sources.

The Vikings raided across Europe, but took the most slaves in raids on the British Isles and in Eastern Europe. While the Vikings kept some slaves as servants, known as thralls, they sold most captives in the Byzantine or Islamic markets. In the West their target populations were primarily English, Irish, and Scottish, while in the East they were mainly Slavs. The Viking slave-trade slowly ended in the 11th century, as the Vikings settled in the European territories they had once raided. They converted serfs to Christianity and themselves merged with the local populace.[155]

Medieval Spain and Portugal saw almost constant warfare between Muslims and Christians. Al-Andalus sent periodic raiding expeditions to loot the Iberian Christian kingdoms, bringing back booty and slaves. In a raid against Lisbon, Portugal in 1189, for example, the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur took 3,000 female and child captives. In a subsequent attack upon Silves, Portugal in 1191, his governor of Córdoba took 3,000 Christian slaves.[156]

The Byzantine-Ottoman wars and the Ottoman wars in Europe resulted in the taking of large numbers of Christian slaves and using or selling them in the Islamic world too.[157] After the battle of Lepanto the victors freed approximately 12,000 Christian galley slaves from the Ottoman fleet.[158]

Similarly, Christians sold Muslim slaves captured in war. The Order of the Knights of Malta attacked pirates and Muslim shipping, and their base became a centre for slave trading, selling captured North Africans and Turks. Malta remained a slave market until well into the late 18th century. One thousand slaves were required to man the galleys (ships) of the Order.[159][160]

Poland banned slavery in the 15th century; in Lithuania, slavery was formally abolished in 1588; the institution was replaced by the second enserfment. Slavery remained a minor institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter the Great converted the household slaves into house serfs. Russian agricultural slaves were formally converted into serfs earlier, in 1679.[161] The escaped Polish and Russian serfs and kholops formed autonomous communities in the southern steppes, where they became known as Cossacks (meaning "outlaws").[162]

British Isles

Capture in war, voluntary servitude and debt slavery became common within the British Isles during the Middle Ages. Slaves were routinely bought and sold. Running away was also common and slavery was never a major economic factor in the British Isles during the Middle Ages. Ireland and Denmark provided markets for captured Anglo-Saxon and Celtic slaves. Pope Gregory I reputedly made the pun, Non Angli, sed Angeli ("Not Angles, but Angels"), after a response to his query regarding the identity of a group of fair-haired Angles, slave children whom he had observed in the marketplace. After 1100 slavery faded away as uneconomical.[163]

Barbary pirates and Maltese corsairs

Barbary pirates and Maltese corsairs both raided for slaves and purchased slaves from European merchants, often the Jewish Radhanites, one of the few groups who could easily move between the Christian and Islamic worlds.[164] Records of Jewish participation in the slave trade go back to the 5th century.[165] Olivia Remie Constable wrote: "Muslim and Jewish merchants brought slaves into al-Andalus from eastern Europe and Christian Spain, and then re-exported them to other regions of the Islamic world."[164] The etymology of the English word slave recalls this period, as the word sklabos means Slav.[166][167]

Venice

In the late Middle Ages, from 1100 to 1500, the European slave-trade continued, though with a shift from being centered among the Western Mediterranean Islamic nations to the Eastern Christian and Muslim states. The city-states of Venice and Genoa controlled the Eastern Mediterranean from the 12th century and the Black Sea from the 13th century. They sold both Slavic and Baltic slaves, as well as Georgians, Turks, and other ethnic groups of the Black Sea and Caucasus. The sale of European slaves by Europeans slowly ended as the Slavic and Baltic ethnic groups Christianized by the Late Middle Ages.[168] European slaves did not pass on an inherited status, and was thus more akin to forced labor, or indentured servitude.

From the 1440s into the 18th century, Europeans from Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and England were sold into slavery by North Africans.[169] as described in the book "Christian Slaves White Masters". This same book controversially states that "white slavery had been minimised or ignored because academics preferred to treat Europeans as evil colonialists rather than as victims." and likely overestimates the number of slaves taken.[170] In 1575, the Tatars captured over 35,000 Ukrainians; a 1676 raid took almost 40,000. About 60,000 Ukrainians were captured in 1688; some were ransomed, but most were sold into slavery.[171][172] Some of the Roma people were enslaved over five centuries in Romania until abolition in 1864 (see Slavery in Romania).[173]

Mongols

The Mongol invasions and conquests in the 13th century also resulted in taking numerous captives into slavery.[174] The Mongols enslaved skilled individuals, women and children and marched them to Karakorum or Sarai, whence they were sold throughout Eurasia. Many of these slaves were shipped to the slave market in Novgorod.[175][176][177]

Slave commerce during the Late Middle Ages was mainly in the hands of Venetian and Genoese merchants and cartels, who were involved in the slave trade with the Golden Horde. In 1382 the Golden Horde under Khan Tokhtamysh sacked Moscow, burning the city and carrying off thousands of inhabitants as slaves. Between 1414 and 1423, some 10,000 eastern European slaves were sold in Venice.[178] Genoese merchants organized the slave trade from the Crimea to Mamluk Egypt. For years, the Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan routinely made raids on Russian principalities for slaves and to plunder towns. Russian chronicles record about 40 raids by Kazan Khans on the Russian territories in the first half of the 16th century.[179]

In 1441 Haci I Giray declared independence from the Golden Horde and established the Crimean Khanate. For a long time, until the early 18th century, the khanate maintained an extensive slave-trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. In a process called the "harvesting of the steppe" they enslaved many Slavic peasants. About 30 major Tatar raids were recorded into Muscovite territories between 1558 and 1596.[180]

Moscow was repeatedly a target. In 1521, the combined forces of Crimean Khan Mehmed Giray and his Kazan allies attacked the city and captured thousands of slaves.[181] In 1571, the Crimean Tatars attacked and sacked Moscow, burning everything but the Kremlin and taking thousands of captives as slaves. In Crimea, about 75% of the population consisted of slaves.[182]

The Vikings and Scandinavia

In the Viking era beginning circa 793, the Norse raiders often captured and enslaved militarily weaker peoples they encountered. The Nordic countries called their slaves thralls (Old Norse: Þræll).[155] The thralls were mostly from Western Europe, among them many Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and Celts. Many Irish slaves travelled in expeditions for the colonization of Iceland.[183] The Norse also took German, Baltic, Slavic and Latin slaves. The slave trade was one of the pillars of Norse commerce during the 6th through 11th centuries. The 10th-century Persian traveller Ibn Rustah described how Swedish Vikings, the Varangians or Rus, terrorized and enslaved the Slavs taken in their raids along the Volga River. The thrall system was finally abolished in the mid-14th century in Scandinavia.[184]

Modern era

Mediterranean powers frequently sentenced convicted criminals to row in the war-galleys of the state (initially only in time of war).[185] After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and Camisard rebellion, the French Crown filled its galleys with French Huguenots, Protestants condemned for resisting the state.[186] Galley-slaves lived and worked in such harsh conditions that many did not survive their terms of sentence, even if they survived shipwreck and slaughter or torture at the hands of enemies or of pirates.[187] Naval forces often turned 'infidel' prisoners-of-war into galley-slaves. Several well-known historical figures served time as galley slaves after being captured by the enemy—the Ottoman corsair and admiral Turgut Reis and the Knights Hospitaller Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette among them.[188]

Denmark-Norway was the first European country to ban the slave trade.[189] This happened with a decree issued by king Christian VII of Denmark in 1792, to become fully effective by 1803. Slavery as an institution was not banned until 1848. At this time Iceland was a part of Denmark-Norway but slave trading had been abolished in Iceland in 1117 and had never been reestablished.[190]

Slavery in the French Republic was abolished on 4 February 1794, including in its colonies. The lengthy Haitian Revolution by its slaves and free people of color established Haiti as a free republic in 1804 ruled by blacks, the first of its kind.[82] At the time of the revolution, Haiti was known as Saint-Domingue and was a colony of France.[191] Napoleon Bonaparte gave up on Haiti in 1803, but re-established slavery in Guadeloupe and Martinique in 1804, at the request of planters of the Caribbean colonies. Slavery was permanently abolished in the French empire during the French Revolution of 1848.

Portugal

The 15th-century Portuguese exploration of the African coast is commonly regarded as the harbinger of European colonialism. In 1452, Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas, granting Afonso V of Portugal the right to reduce any "Saracens, pagans and any other unbelievers" to hereditary slavery which legitimized slave trade under Catholic beliefs of that time. This approval of slavery was reaffirmed and extended in his Romanus Pontifex bull of 1455. These papal bulls came to serve as a justification for the subsequent era of slave trade and European colonialism. Although for a short period as in 1462, Pius II declared slavery to be "a great crime".[192] The followers of the church of England and Protestants did not use the papal bull as a justification. The position of the church was to condemn the slavery of Christians, but slavery was regarded as an old established and necessary institution which supplied Europe with the necessary workforce. In the 16th century, African slaves had replaced almost all other ethnicities and religious enslaved groups in Europe.[193] Within the Portuguese territory of Brazil, and even beyond its original borders, the enslavement of Native Americans was carried out by the Bandeirantes.

Among many other European slave markets, Genoa, and Venice were some well-known markets, their importance and demand growing after the great plague of the 14th century which decimated much of the European work force.[194] The maritime town of Lagos, Portugal, was the first slave market created in Portugal for the sale of imported African slaves, the Mercado de Escravos, which opened in 1444.[195][196] In 1441, the first slaves were brought to Portugal from northern Mauritania.[196] Prince Henry the Navigator, major sponsor of the Portuguese African expeditions, as of any other merchandise, taxed one fifth of the selling price of the slaves imported to Portugal.[196] By the year 1552 African slaves made up 10 percent of the population of Lisbon.[197][198] In the second half of the 16th century, the Crown gave up the monopoly on slave trade and the focus of European trade in African slaves shifted from import to Europe to slave transports directly to tropical colonies in the Americas—in the case of Portugal, especially Brazil.[196] In the 15th century, one third of the slaves were resold to the African market in exchange of gold.[193]

As Portugal increased its presence along China's coast, they began trading in slaves. Many Chinese slaves were sold to Portugal.[199][200] Since the 16th century, Chinese slaves existed in Portugal, most of them were Chinese children and a large number were shipped to the Indies.[201] Chinese prisoners were sent to Portugal, where they were sold as slaves, they were prized and regarded better than moorish and black slaves.[202] The first known visit of a Chinese person to Europe dates to 1540, when a Chinese scholar, enslaved during one of several Portuguese raids somewhere on the southern China coast, was brought to Portugal. Purchased by João de Barros, he worked with the Portuguese historian on translating Chinese texts into Portuguese.[203] Dona Maria de Vilhena, a Portuguese noble woman from Évora, Portugal, owned a Chinese male slave in 1562.[204][205][206] In the 16th century, a small number of Chinese slaves, around 29–34 people were in southern Portugal, where they were used in agricultural labor.[207] Chinese boys were captured in China, and through Macau were brought to Portugal and sold as slaves in Lisbon. Some were then sold in Brazil, a Portuguese colony.[208][209][210] Due to hostility from the Chinese regarding the trafficking in Chinese slaves, in 1595 a law was passed by Portugal banning the selling and buying of Chinese slaves.[211] On 19 February 1624, the King of Portugal forbade the enslavement of Chinese of either sex.[212][213]

Spain

The Spaniards were the first Europeans to use African slaves in the New World on islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola, due to a shortage of labor caused by the spread of diseases, and so the Spanish colonists gradually became involved in the Atlantic slave trade. The first African slaves arrived in Hispaniola in 1501;[214] by 1517, the natives had been "virtually annihilated" mostly to diseases.[215] The problem of the justness of Native American's slavery was a key issue for the Spanish Crown. It was Charles V who gave a definite answer to this complicated and delicate matter. To that end, on 25 November 1542, the Emperor abolished slavery by decree in his Leyes Nuevas New Laws. This bill was based on the arguments given by the best Spanish theologists and jurists who were unanimous in the condemnation of such slavery as unjust; they declared it illegitimate and outlawed it from America—not just the slavery of Spaniards over Natives—but also the type of slavery practiced among the Natives themselves[216] Thus, Spain became the first country to officially abolish slavery.

However, in the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico, where sugarcane production was highly profitable based on slave labor, African slavery persisted until 1873 in Puerto Rico "with provisions for periods of apprenticeship",[217] and 1886 in Cuba.[218]

Netherlands

Although slavery was illegal inside the Netherlands it flourished in the Dutch Empire, and helped support the economy.[219] By 1650 the Dutch had the pre-eminent slave trade in Europe.[220] As of 1778, it was estimated that the Dutch were shipping approximately 6,000 Africans for enslavement in the Dutch West Indies each year.[80] The Dutch shipped about 550,000 African slaves across the Atlantic, about 75,000 of whom died on board before reaching their destinations. From 1596 to 1829, the Dutch traders sold 250,000 slaves in the Dutch Guianas, 142,000 in the Dutch Caribbean islands, and 28,000 in Dutch Brazil.[221] In addition, tens of thousands of slaves, mostly from India and some from Africa, were carried to the Dutch East Indies.[222]

Barbary corsairs

_-_Copy.jpg)

Barbary Corsairs continued to trade in European slaves into the Modern time-period.[168] Muslim pirates, primarily Algerians with the support of the Ottoman Empire, raided European coasts and shipping from the 16th to the 19th centuries, and took thousands of captives, whom they sold or enslaved. Many were held for ransom, and European communities raised funds such as Malta's Monte della Redenzione degli Schiavi to buy back their citizens. The raids gradually ended with the naval decline of the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th and 17th centuries, as well as the European conquest of North Africa throughout the 19th century.[168]

From 1609 to 1616, England lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates. 160 English ships were captured by Algerians between 1677 and 1680.[224] Many of the captured sailors were made into slaves and held for ransom. The corsairs were no strangers to the South West of England where raids were known in a number of coastal communities. In 1627 Barbary Pirates under command of the Dutch renegade Jan Janszoon operating from the Moroccan port of Salé occupied the island of Lundy.[225] During this time there were reports of captured slaves being sent to Algiers.[226][227]

Ireland, despite its northern position, was not immune from attacks by the corsairs. In June 1631 Murat Reis, with pirates from Algiers and armed troops of the Ottoman Empire, stormed ashore at the little harbor village of Baltimore, County Cork. They captured almost all the villagers and took them away to a life of slavery in North Africa.[228] The prisoners were destined for a variety of fates—some lived out their days chained to the oars as galley slaves, while others would spend long years in the scented seclusion of the harem or within the walls of the sultan's palace. Only two of them ever saw Ireland again.

The Congress of Vienna (1814–15), which ended the Napoleonic Wars, led to increased European consensus on the need to end Barbary raiding. The sacking of Palma on the island of Sardinia by a Tunisian squadron, which carried off 158 inhabitants, roused widespread indignation. Britain had by this time banned the slave trade and was seeking to induce other countries to do likewise. States that were more vulnerable to the corsairs complained that Britain cared more for ending the trade in African slaves than stopping the enslavement of Europeans and Americans by the Barbary States.

In order to neutralise this objection and further the anti-slavery campaign, in 1816 Britain sent Lord Exmouth to secure new concessions from Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers, including a pledge to treat Christian captives in any future conflict as prisoners of war rather than slaves. He imposed peace between Algiers and the kingdoms of Sardinia and Sicily. On his first visit, Lord Exmouth negotiated satisfactory treaties and sailed for home. While he was negotiating, a number of Sardinian fishermen who had settled at Bona on the Tunisian coast were brutally treated without his knowledge. As Sardinians they were technically under British protection, and the government sent Exmouth back to secure reparation. On 17 August, in combination with a Dutch squadron under Admiral Van de Capellen, Exmouth bombarded Algiers. Both Algiers and Tunis made fresh concessions as a result.

The Barbary states had difficulty securing uniform compliance with a total prohibition of slave-raiding, as this had been traditionally of central importance to the North African economy. Slavers continued to take captives by preying on less well-protected peoples. Algiers subsequently renewed its slave-raiding, though on a smaller scale. Europeans at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818 discussed possible retaliation. In 1820 a British fleet under Admiral Sir Harry Neal bombarded Algiers. Corsair activity based in Algiers did not entirely cease until France conquered the state in 1830. [228]

Crimean Khanate

The Crimeans frequently mounted raids into the Danubian principalities, Poland-Lithuania, and Muscovy to enslave people whom they could capture; for each captive, the khan received a fixed share (savğa) of 10% or 20%. These campaigns by Crimean forces were either sefers ("sojourns"), officially declared military operations led by the khans themselves, or çapuls ("despoiling"), raids undertaken by groups of noblemen, sometimes illegally because they contravened treaties concluded by the khans with neighbouring rulers.

For a long time, until the early 18th century, the khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East, exporting about 2 million slaves from Russia and Poland-Lithuania over the period 1500–1700.[229] Caffa was one of the best known and significant trading ports and slave markets.[230] In 1769, a last major Tatar raid saw the capture of 20,000 Russian and Ruthenian slaves.[231]

Author and historian Brian Glyn Williams writes:

Fisher estimates that in the sixteenth century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lost around 20,000 individuals a year and that from 1474 to 1694, as many as a million Commonwealth citizens were carried off into Crimean slavery.[232]

Early modern sources are full of descriptions of sufferings of Christian slaves captured by the Crimean Tatars in the course of their raids:

It seems that the position and everyday conditions of a slave depended largely on his/her owner. Some slaves indeed could spend the rest of their days doing exhausting labor: as the Crimean vizir (minister) Sefer Gazi Aga mentions in one of his letters, the slaves were often "a plough and a scythe" of their owners. Most terrible, perhaps, was the fate of those who became galley-slaves, whose sufferings were poeticized in many Ukrainian dumas (songs). ... Both female and male slaves were often used for sexual purposes.[231]

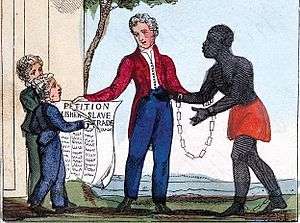

British slave trade

Britain played a prominent role in the Atlantic slave trade, especially after 1600. Slavery was a legal institution in all of the 13 American colonies and Canada (acquired by Britain in 1763). The profits of the slave trade and of West Indian plantations amounted to 5% of the British economy at the time of the Industrial Revolution.[233] The Somersett's case in 1772 was generally taken at the time to have decided that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law in England. In 1785, English poet William Cowper wrote: "We have no slaves at home – Then why abroad? Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs receive our air, that moment they are free. They touch our country, and their shackles fall. That's noble, and bespeaks a nation proud. And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then, And let it circulate through every vein."[234] In 1807, following many years of lobbying by the abolitionist movement, led primarily by William Wilberforce, the British Parliament voted to make the slave trade illegal anywhere in the Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807. Thereafter Britain took a prominent role in combating the trade, and slavery itself was abolished in the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Between 1808 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard.[235] Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade. Atinkoye, the 11th Oba of Lagos, is famous for having used British involvement to regain his rule in return for suppressing slavery among the Yoruba people of Lagos in 1851. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.[236] In 1839, the world's oldest international human rights organization, Anti-Slavery International, was formed in Britain by Joseph Sturge, which worked to outlaw slavery in other countries.[237]

In 1811, Arthur William Hodge was executed for the murder of a slave in the British West Indies. He was not, however, as some have claimed, the first white person to have been lawfully executed for the murder of a slave.[238][239]

Modern Europe

Germany

During World War II Nazi Germany operated several categories of Arbeitslager (Labor Camps) for different categories of inmates. The largest number of them held Jewish civilians forcibly abducted in the occupied countries (see Łapanka) to provide labor in the German war industry, repair bombed railroads and bridges or work on farms. By 1944, 19.9% of all workers were foreigners, either civilians or prisoners of war.[240][241][242][243]

This is not classed as slavery per se, as defined in the first paragraph, i.e. slavery under this definition does not include other forced labour systems, such as historical forced labor by prisoners, labor camps, or other forms of unfree labor, in which labourers are not legally considered property. Slavery typically requires a shortage of labor and a surplus of land to be viable.[3]

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union took over the already extensive katorga system and expanded it immensely, eventually organizing the Gulag to run the camps. In 1954, a year after Stalin's death, the new Soviet government of Nikita Khrushchev began to release political prisoners and close down the camps. By the end of the 1950s, virtually all "corrective labor camps" were reorganized, mostly into the system of corrective labor colonies. Officially, the Gulag was terminated by the MVD order 20 25 January 1960.[244][source needs translation]

During the period of Stalinism, the Gulag labor camps in the Soviet Union were officially called "Corrective labor camps." The term "labor colony"; more exactly, "Corrective labor colony", (Russian: исправительно-трудовая колония, abbr. ИТК), was also in use, most notably the ones for underaged (16 years or younger) convicts and captured besprizorniki (street children, literally, "children without family care"). After the reformation of the camps into the Gulag, the term "corrective labor colony" essentially encompassed labor camps.

The Soviet Union had about 14 million people working in Gulags during its existence.[245]

Allied powers

As agreed by the Allies at the Yalta conference Germans were used as forced labor as part of the reparations to be extracted. By 1947 it is estimated that 400,000 Germans (both civilians and POWs) were being used as forced labor by the U.S., France, the UK and the Soviet Union. German prisoners were for example forced to clear minefields in France and the Low Countries. By December 1945 it was estimated by French authorities that 2,000 German prisoners were being killed or injured each month in accidents.[246] In Norway the last available casualty record, from 29 August 1945, shows that by that time a total of 275 German soldiers died while clearing mines, while 392 had been injured.[247] Death rates for the German civilians doing forced labor in the Soviet Union ranged between 19% and 39%, depending on category.

Oceania

In the first half of the 19th century, small-scale slave raids took place across Polynesia to supply labor and sex workers for the whaling and sealing trades, with examples from both the westerly and easterly extremes of the Polynesian triangle. By the 1860s this had grown to a larger scale operation with Peruvian slave raids in the South Sea Islands to collect labor for the guano industry.

Hawaii

Ancient Hawaii was a caste society. People were born into specific social classes. Kauwa were the outcast or slave class. They are believed to have been war captives, or the descendents of war captives. Marriage between higher castes and the kauwa was strictly forbidden. The kauwa worked for the chiefs and were often used as human sacrifices at the luakini heiau. (They were not the only sacrifices; law-breakers of all castes or defeated political opponents were also acceptable as victims.)[248]

New Zealand

Before the arrival of European settlers, each Māori tribe (iwi) considered itself a separate entity equivalent to a nation. In traditional Māori society of Aotearoa, prisoners of war became taurekareka, slaves, unless released, ransomed or eaten.[249] With some exceptions, the child of a slave remained a slave.

As far as it is possible to tell, slavery seems to have increased in the early 19th century with increased numbers of prisoners being taken by Māori military leaders, such as Hongi Hika and Te Rauparaha to satisfy the need for labor in the Musket Wars, to supply whalers and traders with food, flax and timber in return for western goods. The intertribal Musket Wars lasted 1807 to 1843 when large numbers of slaves were captured by northern tribes who had acquired muskets. About 20,000 Maori died in the wars which were concentrated in the North Island. An unknown number of slaves were captured. Northern tribes used slaves (called mokai) to grow large areas of potatoes for trade with visiting ships. Chiefs started an extensive sex trade in the Bay of Islands in the 1830s using mainly slave girls. By 1835 about 70–80 ships per year called into the port. One French captain described the impossibility of getting rid of the girls who swarmed over his ship out numbering his crew of 70 by 3 to 1. All payments to the girls were stolen by the chief.[250] By 1833 Christianity had become established in the north and large numbers of slaves were freed. However two Taranaki tribes, Ngati Tama and Ngati Mutunga, displaced by the wars carried out a carefully planned invasion of the Chatham Islands, 800 km east of Christchurch, in 1835. About 15% of the Polynesian Moriori natives who had migrated to the islands at about 1500 CE were killed, with many women being tortured to death. The remaining population were enslaved for the purpose of growing food, especially potatoes. The Moriori were treated in an inhumane and degrading manner for many years. Their culture was banned and they were forbidden to marry.[251] Slavery was outlawed when the British annexed New Zealand in 1840, immediately prior to the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, although it did not end completely until government was effectively extended over the whole of the country with the defeat of the Kingi movement in the Wars of the mid-1860s.