The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

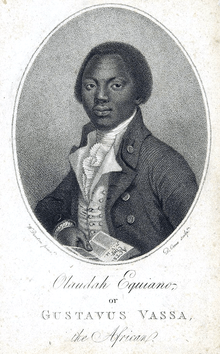

Cover image | |

| Author | Olaudah Equiano |

|---|---|

| Country | Great Britain |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Autobiography |

Publication date | 1789 |

| OCLC | 23633870 |

| LC Class | HT869.E6 A3 1794 |

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, first published in 1789, is the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano. The narrative is argued to be a variety of styles, such as a slavery narrative, travel narrative, and spiritual narrative.[1] The book describes Equiano's time spent in enslavement, and documents his attempts at becoming an independent man through his study of the Bible, and his eventual success in gaining his own freedom and in business thereafter.

Main themes

- Slavery in West Africa and how the experience differed from slavery in the Americas

- The African slave's voyage from Africa (Igboland) to the Americas and England[2]

- The journey from slavery to freedom and parallel journey from heathenism to Christianity

- Institutional slavery can raise the master as above man as the slave is forced beneath, both corrupting the master with power and crippling the slave with the lack thereof

Summary

Preface

Prior to chapter 1, Equiano writes, "An invidious falsehood having appeared in the Oracle of the 25th, and the Star of the 27th of April 1792, with a view to hurt my character, and to discredit and prevent the sale of my Narrative."[3] Like many literary works written by black people during this time, Equiano's work was discredited as a false presentation of his slavery experience. To combat these accusations, Equiano includes a set of letters written by white people who "knew me when I first arrived in England, and could speak no language but that of Africa."[3] In his article, Preface to Blackness: Text and Pretext[4] Henry Louis Gates Jr. discusses the use of prefaces by black authors to humanize their being which in turn made their work credible. In this section of the book, Equiano includes this preface to avoid further discrediting. Other notable works with a "preface to blackness" include the poems of Phyllis Wheatley.

Chapter 1

Equiano's narrative is written in first person as a whole. Prior to beginning his narrative in the first chapter, Equiano includes several letters that identify him as a person. The opening letters explain him as a person and are used to exemplify his character. Before his readers indulge into his narrative, he makes it a priority to ensure that they are aware of his good character. This is a huge key for Equiano as it sets the stage for what is to come in chapter 1.

Equiano opens his Narrative by explaining the struggle that comes with writing a memoir. He is very passionate about the hardships that memoir writers go through. He explains that they often have to defend themselves from those who remain critical about the truth of their work. He apologizes to his readers in advance for not having the most exciting story, but hopes that it serves to be helpful to other slaves in his position. He states, “I am neither a saint, a hero, nor a tyrant.” He begins his story with a description of his homeland and the district in which he was born. He was born in the kingdom of Benin. Benin was a part of Guinea. The specific district that he represented was Eboe. Eboe is in the same area as what is now, Nigeria. Within the district, Equiano was born in Essake, a small province, in 1745. He goes into detail concerning his district and the isolation of his province.[5]

Eboe, Equiano’s district, was very established when it came to rules and laws of governing. Their system of marriage and law were strictly enforced. His father was an elder in the district, and he was in charge of punishing criminals and resolving issues of conflict within the society. Within the district, women were held to higher standards than men. Marriage was seen as extremely important. The bride’s family was responsible for providing gifts for the family of the husband, and the wife was seen as “owned by her husband”.[6]

Dancing was a huge part of the culture within the kingdom. All dancing as separated into four divisions of groups of people, and they all represented an important part of life and an important event in life. The kingdom was made up of many musicians, singers, poets, dancers, and artists. The people of the kingdom lived a simple life. Nothing was luxurious. Clothes and homes were very plain and clean. The only type of luxuries in their eyes were perfumes and on occasions alcohol. Women were in charge of creating clothing for the men and women to wear. But, as far as occupation goes, agriculture was the primary occupation. The kingdom sat on rich soil, thus allowing for health food and abundant growth. Slaves were also present in the kingdom, but in Eboe, only slaves who were prisoners of war or convicted criminals were traded.

Some hardships came with an unusual amount of locusts and nonstop, random wars with other districts. If another district’s chief waged war and won, then they would acquire all slaves, but in losses, the chief would be put to death. Religion was extremely important in the Equiano’s society. The people of Eboe believed in one “Creator”. They believed that the Creator lived in the sun and was in charge of major occurrences: life, death, and war. They believed that those who died transmigrated into spirits, but their friends and family who did not transmigrate protected them from evil spirits. They believed in circumcision. Equiano compared this practice of circumcision to that of the Jews.

Equiano goes on to explain the customs of his people. Children were named after events or virtues of some sort. Olaudah meant fortune, but it also served as a symbol of command of speech and his demanding voice. Two of the main themes of the Eboe religion were cleanliness and decency. Touching of women during their menstrual cycle and the touching of dead bodies were seen as unclean. As Equiano discusses his people, he explains the fear of poisons within the community. Snakes and plants contained poisons that were harmful to the Eboe people. He describes an instance where a snake once slithered through his legs without harming him. He considered himself extremely lucky.[7]

Equiano makes numerous references to the similarity between the Jews and his people. Like the Jews, not only did his people practise circumcision, but they also practised sacrificing, burnt offerings, and purification. He explains how Abraham’s wife was African, and that the skin colour of Eboan Africans and modern Jews differs due to the climate difference. At the end of the first chapter, Equiano asserts that Africans were not inferior people. The Europeans saw them as inferior because they were ignorant of the European language, history, and customs. He explains that it is important to remember that the ancestors of the Europeans were once uncivilized and barbarians at one point or another. He states, “Understanding is not confined to feature or colour.”

Chapter 2

Equiano begins the chapter by explaining how he and his sister were kidnapped. The pair are forced to travel with their captors for a time, when one day the two children are separated. Equiano becomes the slave-companion to the children of a wealthy chieftain. He stays there for about a month, when he runs away after accidentally killing one of his master's chickens. Equiano hides in the shrubbery and woods surrounding his master's village, but after several days without food, steals away into his master's kitchen to eat. Exhausted, Equiano falls asleep in the kitchen and is discovered by another slave who takes Equiano to the master. The master is forgiving and insists that Equiano shall not be harmed.

Soon after, Equiano is sold to a group of travellers. One day, his sister appears with her master at the house and they share a joyous reunion. However, soon afterward she and her company departs, and Equiano never sees his sister again. Equiano is eventually sold to a wealthy widow and her young son. Equiano lives almost as an equal among them and is very happy until he is again taken away and forced to travel with "heathens" to the seacoast.[8]

Equiano is forced onto a slave ship and spends the next several weeks on the ship under terrible conditions. He points out the "closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship" suffocates them; some slaves even preferred to drown, and one was saved but to be flogged later, as he had chosen to die rather that accept to be a slave. At last they reach the island of Barbados, where Equiano and all the other slaves are separated and sold. The author mentions the impact of their selling away, as "on the signal given, (as the beat of a drum), the buyers rush at once into the yard where they are confined, and make choice of that parcel they like best. [...] The noise and clamour [...] serve not a little to increase the apprehension of the Terrified Africans."

Throughout the whole passage, Equiano refers to white people as cruel, greedy and mean, and is very surprised by the way they relate to each other, as they are even cruel between them, not only to the slaves. However, as he meets more white people and learns about their culture he comes to the conclusion that the white men are not inherently evil but that institutional slavery has made them cruel and callous.

Chapter 3

Equiano was lonely at the new plantation and didn’t have anyone to talk to. He did his work by himself. One day, when he was in the kitchen, he saw one of the women slaves with an iron muzzle on, and that shocked him. As he continued looking around the house he saw a watch on the wall and a painting. He was paranoid by both of these objects because he thought they were spying for the Master. This shows just how little he knew about the common technology of the time. On the plantation he was called Jacob, instead of his real name. One day, a man, whose name is Michael Henry Pascal, came to the Master's house and wanted to purchase Equiano. He paid thirty to forty pounds for him and Equiano left to work on a ship. He liked it a lot better on the ship because the other people aboard were nicer to him and he ate better than he did previously. He was renamed again to Gustavus Vassa, which he didn’t like but got used to so he didn’t get punished. On the ship Equiano made a friend whose name was Richard Baker. Richard became a companion and interpreter for Equiano because he didn’t understand the language everyone else was speaking. They became very close. Richard died in 1759 and it was hard on Equiano.[9]

Chapter 4

It has now been two or three years since Equiano first came to England. He has spent the majority of his time at sea. He didn’t mind the work he was doing and has spent so much time there he almost considered himself an Englishman. He could speak English decently, but he could perfectly understand everything that was being said to him. He also started viewing the others on the ship as superiors to him instead of barbaric and scary. He wanted to be like them. Equiano went to London with his Master and was sent to serve for the Guerins. He liked it there and they provided him an education. He got baptized with the help of Miss Guerins. After a while his Master got called back to sea, so Equiano had to leave school to work for his Master. They went to Gibraltar, which allowed him to get cheap fruit and tell the story of losing his sister. A person who lived in the area told him that he saw his sister and took him to her, but it ended up not being his sister. Equiano met Daniel Queen while working for his Master and he quickly became a big part of his life. He taught him a variety of things like religion, education, and how to shave. Equiano viewed him almost like a father and tried to repay him with sugar or Tabaco whenever he could afford it. The ship left to go to London in December because they heard talk to peace and the end of the war. When they got there his Master gave him away to Captain Doran, even though he didn’t want to go.[9]

Chapter 5

In the middle of May, Equiano was summoned by Captain Doran and was told he had been sold to a new Master, whose name was Mr. Robert King. King wanted to purchase him because he liked his character and how much of a hard worker he is. Other people offered King up to one hundred guineas for Equiano. King was good to Equiano and said he would put him in school and fit him for a clerk. King feed his slaves good and sometimes got criticized by others for it. King’s philosophy was: the better fed the slave; the harder the slave would work. King had Equiano do a new job on the ship, which is called gauging. Gauging is measuring the depth of the boat or a compartment of a boat. He also put Equiano in charge of the Negro cargo on the ship. While working for King, Equiano saw clerks and other white men rape women, which made him angry, especially because he couldn’t do anything about it.[9]

Chapter 6

Chapter six opens with Equiano explaining that he has seen a lot of bad and unfair things happen as a slave. He recounts a specific event that happened in 1763. He and a companion were trying to sell limes and oranges that were in bags. Two white men came up to them and took the fruit away from them. They begged them for the bags back and explained that it was everything they owned, but the white men threatened to flog them if they continued begging. They walked away because they were scared, but after a while they went back to the house and asked for their stuff back again. The men gave them two of the three bags back. The bag that they kept was all of the companions fruit, so Equiano gave him about one-third of his fruit. They went off to sell the fruit and ended up getting 37 bits for it, which was surprising. During this time Equiano started working as a sailor and selling and trading items like gin and tumblers. When he was in the West Indies, he witnessed a free mulatto man, whose name is Joseph Clipson, be taken in and made a slave by a white man. Equiano says that happens a lot in that area. He decides that he can’t be free until he leaves the West Indies. With the money he is earning from selling items he is saving it to buy his freedom.[9]

Before Equiano and his captain leave for a trip to Philadelphia, his captain hears that Equiano was planning on running away. His Master reminds him how valuable he is and how he will just find him and get him back if he tries to run away. Equiano explains that he didn’t plan on running away and if he wanted to run away he would have done it by now given all the freedom the Master and the captain give him. The captain confirms what Equiano said and decided it was just a rumor. Equiano tells the Master then that he is interested in buying his freedom eventually.[9]

When they get to Philadelphia, he goes and sells what his Master gave him and also talked to Mrs. Davis. Mrs. Davis is a wise woman who reveals secrets and foretells events. She tells him he wouldn’t be a slave for long. The ship continues on to Georgia and while they are there, Doctor Perkins beats Equiano up and leaves him laying on the ground unable to move. Police pick him up and put him in jail. His captain finds out when he doesn’t come back the night before and gets him out of jail. He also has the best doctors treat him. He tries to sue Doctor Perkins, but a lawyer explains that there is not a case because Equiano is a black man. Equiano slowly recovers and gets back to work.[9]

Chapter 7

Equiano is getting close to purchasing his freedom with all the money he has saved from selling items. The ship was supposed to go to Montserrat, where he thought he would get the last of the money he needed, but they get an order to go to St. Eustatia and then Georgia instead. He sells some more items and earned enough money to buy his freedom. He goes to the captain to consult with him about what to say to his Master. The captain says to come by on a certain morning when he and the Master will be having breakfast. He goes in that day and proposes to purchase his own freedom for 70 pounds. With a little convincing from the captain, he agrees, and Equiano is granted complete freedom. The narrative ends with Equiano’s Montserrat in full text.[9]

Controversy about origins

Decades after The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, was published and newly edited in 1967 by Paul Edwards a debate was sparked on the validity of the origins of Equiano’s story.

In 1999, Vincent Carretta published findings of two records, a baptismal record and a naval muster roll, he found question Equiano's account of being born in Africa.[10] Carretta believes that his findings are possible evidence that Equiano had borrowed his account of Africa from others. Carretta goes on to say the timing of the publication of The Interesting Narrative was not an accident,[11] noting “the revelation that Gustavus Vassa was a native-born Igbo originally named Olaudah Equiano appears to have evolved during 1788 in response to the needs of the abolitionist movement.”[12]

Carretta explains that Equiano presumably knew what parts of his story could be corroborated by others, and, more importantly if he was combining fiction with fact, what parts could not easily be contradicted.[11]

“Equiano’s fellow abolitionists were calling for precisely the kind of account of Africa and the Middle Passage that he supplied. Because only a native African would have experienced the Middle Passage, the abolitionist movement needed an African, not an African-American, voice. Equiano’s autobiography corroborated and even explicitly drew upon earlier reports of Africa and the Middle Passage by some white observers, and challenged those of others.”

Paul E. Lovejoy disputes Carretta’s claim that Vassa was born in South Carolina because of Vassa’s knowledge of the Igbo society. Lovejoy refers to Equiano as Vassa because he never used his African name until he wrote his narrative.[13] Lovejoy believes Vassa's description of his country and his people is sufficient confirmation that he was born where he said he was, and based on when boys received the ichi scarification, that he was about 11 when he was kidnapped, as he claims, which suggests a birth date of ca. 1742, not 1745 or 1747.[14]

Lovejoy thoughts on the baptismal record are that Vassa couldn't have made up his origins because he would have been too young. Lovejoy goes on to say[14]

If Carretta is correct about Vassa's age at the time of baptism, accepting the documentary evidence, then he was too young to have created a complex fraud about origins. The fraud must have been perpetrated later, but when? Certainly the baptismal record cannot be used as proof that he committed fraud, only that his godparents might have.

Lovejoy also believes that Equiano’s godparents, the Guerins and Pascals, wanted people to think that Vassa was creole born, and not a native African, because he had mastered English so well by then or for other reasons relating to perceived higher status for creoles.[15]

In 2007, Carretta wrote a response to Lovejoy’s claims about the Equiano’s Godparents saying, “Lovejoy can offer no evidence for such a desire or perception.” [11] Carretta goes on to say, “Equiano’s age on the 1759 baptismal record to be off by a year or two before puberty is plausible. But to have it off by five years, as Lovejoy contends, would place Equiano well into puberty at the age of 17, when he would have been far more likely to have had a say in, and later remembered, what was recorded. And his godparents and witnesses should have noticed the difference between a child and an adolescent.” [16]

Reception

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano was one of the first widely read slave narratives. Eight editions were printed during the author's lifetime, and it was translated into Dutch and German.[17] The structure and rhetorical strategies of the book were influential and created a model for subsequent slave narratives.[17] The different kinds of aspects and ideas in his narrative, such as travel, religion, and slavery, cause some readers to debate what kind of narrative his writing is: a slavery narrative, a spiritual narrative, or a travel narrative.[1]

The work has proven so influential in the study of African and African American literature, that it is frequently taught in both English literature and History classrooms in universities. The work has also been republished in the influential Heinemann African Writers Series.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Collins, Janelle (2006). "Passage to Slavery, Passage to Freedom: Olaudah Equiano and the Sea". Midwest Quarterly. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ Gates 1989, p. 154.

- 1 2 Louis Gates Jr, Henry (2012). The Classic Slave Narratives. New American Library. p. 3. ISBN 9780451532138.

- ↑ Louis Gates Jr., Henry. "Preface to Blackness: Text and Pretext". Afro-American Literature: The Reconstruction of Instruction.

- ↑ Carey, Brycchan. "Olaudah Equiano: An Illustrated Biography". Brycchan Carey homepage. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Public Broadcasting Service. "Africans in America:Part 1-Olaudah Equiano". www.pbs.org. Resource Bank: Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ The Equiano Project (2007). "Olaudah Equiano: 1745–1797". www.equiano.org. Worcestershire Records Office. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ "Equiano in Africa". IMDb. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Equiano, Olaudah (2013). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself. United States of America: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 355–387. ISBN 978-0-393-91885-4.

- ↑ Blackburn, Robin. "The True Story of Equiano". The Nation.

- 1 2 3 Carretta, Vincent (2007). "Response to Paul Lovejoy's 'Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African'". Slavery & Abolition. 28 (1): 116.

- ↑ Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African : Biography of a self-made man. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ Lovejoy, Paul E. (2006). "Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African.". Slavery And Abolition. 27 (3): 318.

- 1 2 Lovejoy, Paul E. (2006). "Construction of Identity: Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa?". Historically Speaking. 7 (3): 9.

- ↑ Lovejoy, Paul E. (2006). "Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African.". Slavery And Abolition. 27 (3): 337.

- ↑ Carretta, Vincent (2007). "Response to Paul Lovejoy's 'Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African'". Slavery & Abolition. 28 (1): 118.

- 1 2 Gates 1989, p. 153.

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Equiano, Olaudah (2001), Sollors, Werner, ed., The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African written by himself; authoritative text, contexts, criticism (1st ed.), New York: Norton, ISBN 0393974944, LCCN 00058386

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. (1989). The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195060751.

External links

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African at Project Gutenberg

- Catalog record for The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African at the United States Library of Congress

-

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano: A short animation partially adapted from the book with a third act set in 1838 when slavery is abolished.

- "North American Slave Narratives: Alphabetical List of Slave and Ex-Slave Narratives". Documenting the American South. The University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2004. Retrieved 12 September 2012.