Hongi Hika

Hongi Hika (c. 1772 – 6 March 1828) was a New Zealand Māori rangatira (chief) and war leader of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe).

Hongi Hika used European weapons to overrun much of northern New Zealand in the first of the Musket Wars. He also encouraged Pākehā (European) settlement, patronised New Zealand's first missionaries, introduced Māori to Western agriculture and helped put the Māori language into writing. He travelled to England and met King George IV. Hongi Hika's military campaigns, and the other Musket Wars were one of the most important stimuli for the British annexation of New Zealand and subsequent Treaty of Waitangi with Ngāpuhi and many other iwi. He was a pivotal figure in the period when Māori history emerged from myth and oral tradition and Pākehā began to settle rather than just visit.

Born

Hongi Hika was born at Kaikohe into one of the chiefly families of the Ngāpuhi, being a son of rangatira Te Hotete. Hongi Hika once said he was born in the year explorer Marion du Fresne was killed by Māori—in 1772—though other sources place his birth around 1780.

Early campaigns, 1806–1814

Hongi Hika rose to prominence as a military leader in the Ngāpuhi campaign, led by Pokaia, against the Te Roroa hapu of Ngāti Whātua iwi in 1806–1808. In over 150 years since the Maori first begun sporadic contact with Europeans, firearms had not entered into widespread use. Ngāpuhi fought with small numbers of them in 1808, and Hongi Hika was present later that same year on the first occasion that muskets were used in action by Māori. This was at the battle of Moremonui at which the Ngāpuhi were defeated;[1] the Ngāpuhi were overrun by the opposing Ngāti Whātua while reloading. Those killed included two of Hongi Hika's brothers and Pokaia, and Hongi Hika and other survivors only escaped by hiding in a swamp until Ngāti Whātua called off the pursuit to avoid provoking utu.

Hongi Hika became the war leader of the Ngāpuhi, his warriors included Te Ruki Kawiti, Mataroria, Moka Te Kainga-mataa, Rewa, Ruatara, Paraoa, Motiti, Hewa and Mahanga.[2] In 1812 he led a large taua (war party) to the Hokianga against Ngāti Pou. Despite his earlier experiences he seems to have become convinced of the value of muskets which were used during this campaign. In 1825 Hongi avenged the earlier defeat of Moremonui in the battle of Te Ika-a-Ranganui, although both sides suffered heavy losses.[1]

Contact with Europeans and journey to Australia, 1814–1819

Ngāpuhi controlled the Bay of Islands, the first point of contact for most Europeans visiting New Zealand in the early 19th century. Hongi Hika protected early missionaries and European seamen and settlers, arguing the benefits of trade. He befriended Thomas Kendall—one of three lay preachers sent by the Church Missionary Society to establish a Christian toehold in New Zealand.

In 1814 Hongi Hika and his nephew Ruatara, the then-leader of the Ngāpuhi, visited Sydney, Australia, with Kendall and met the local head of the Church Missionary Society Samuel Marsden. Ruatara and Hongi Hika invited Marsden to establish the first Anglican mission to New Zealand in Ngāpuhi territory.[3] Ruatara died the following year, leaving Hongi Hika as protector of the mission. In 1817 Hongi led a war party to Thames where he attacked the Ngati Maru stronghold of Te Totara, killing 60 and taking 2000 prisoners.[4]

On 4 July 1819 he granted 13,000 acres of land at Kerikeri to the Church Missionary Society in return for 48 felling axes,[5] land which became known as the Society's Plains. He personally assisted the missionaries in developing a written form of the Māori language.

Hongi Hika never converted to Christianity. In later life, in exasperation with teachings of humility and non-violence, he described Christianity as “a religion fit only for slaves”. He protected the Pākehā Māori Thomas Kendall when he effectively “went native”, taking a Māori wife and participating in Māori religious ceremonies. Though Hongi Hika encouraged the first missions to New Zealand, virtually no Māori converted to Christianity for a decade; large scale conversion of northern Māori only occurred after his death.

While in Australia Hongi Hika studied European military and agricultural techniques and purchased muskets and ammunition. From 1818 he introduced European agricultural implements and the potato, using slave labour to produce crops for trade.

Wives

Hongi married Turikatuku, who was an important military advisor for him, although she went blind early in their marriage. He later took her sister Tangiwhare as additional wife. Both bore at least one son and daughter by him. It is uncertain if he had other wives.

Bay of Plenty campaign, 1818–1819

In 1818 Hongi Hika led one of two Ngāpuhi taua against East Cape and Bay of Plenty iwi Ngāti Porou and Ngaiterangi. The taua returned in 1819 carrying nearly 2,000 captured slaves.

Journey to England, 1819–1821

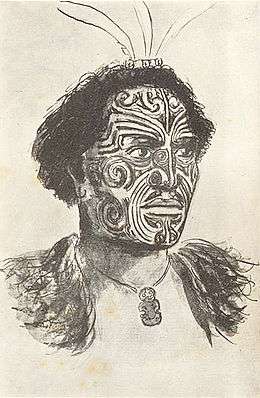

In 1820 Hongi Hika and Thomas Kendall travelled to England on board the whaling ship New Zealander.[6] He spent 5 months in London and Cambridge where his facial tattoos made him something of a sensation. During the trip he met King George IV who presented him with a suit of armour. He continued his linguistic work, assisting Professor Samuel Lee who was writing the first Māori–English dictionary. Written Māori maintains a northern feel to this day as a result—for example the sound usually pronounced "f" in Māori is written "wh" because of Hongi Hika's soft aspirated northern dialect.

Campaigns against Ngāti Whātua, Waikato and Rotorua, 1821–1825

Hongi Hika returned to the Bay of Islands in July 1821, after 457 days away, via Sydney Australia where he picked up an estimated 500 muskets that were waiting for him. The muskets had been ordered by Baron Charles de Thierry whom Hongi met at Cambridge, England. De Theirry traded the muskets for land in the Hokianga,[7] although De Theirry's claim to the land was later disputed. Hongi was able to uplift the guns without them being paid for. He also had a large quantity of gunpowder, ball ammunition, swords and daggers. Using these within months of his return he led his warriors against those of the Ngāti Pāoa chief, Te Hinaki, which resulted in the death of Hinaki around 1,000 of his warriors at Moaki.[8][9] He then led a force of about 2,000 men to attack a pa (Māori fort) at (Panmure) on the Tamaki River, killing 2,000 warriors and their women and children in retribution for a previous defeat. Deaths in this one action during the intertribal Musket Wars outnumber all deaths in 25 years of the sporadic New Zealand Wars.

In early 1822 he led his force up the Waikato River where, after initial success, he was defeated by Te Wherowhero, before gaining another victory at Orongokoekoea. Te Wherowhero ambushed the Ngāpuhi carrying Ngāti Mahuta women captives and freed them. In 1823 he made peace with the Waikato iwi and invaded Te Arawa territory in Rotorua.

In 1824–5 Hongi Hika attacked Ngāti Whātua again, losing 70 men, including his eldest son Hare Hongi, in the battle of Te Ika a Ranganui. According to some accounts Ngāti Whātua lost 1,000 men—although Hongi Hika himself, downplaying the tragedy, put the number at 100. In any event the defeat was a catastrophe for Ngāti Whātua—the survivors retreated south.[1] They left behind the fertile region of Tāmaki Makaurau (the Auckland isthmus) with its vast natural harbours at Waitemata and Manukau—land which had belonged to Ngāti Whātua since they won it by conquest over a hundred years before. Hongi Hika left Tāmaki Makaurau almost uninhabited as a southern buffer zone. Fifteen years later when Lt. Governor William Hobson wished to remove his fledging colonial administration from settler and Ngāpuhi influence in the Bay of Islands, he was able to purchase this land cheaply from Ngāti Whātua, to build Auckland, a settlement that has become New Zealand’s principal city.

Although Māori population had always been, to some extent, mobile in the face of conquests of land, during the Musket Wars Hongi Hika altered the balance of power not only in the Waitemata but also the Bay of Plenty, Tauranga, Coromandel, Rotorua and Waikato to an extent which seems unprecedented within the memory of his contemporaries. Although he did not usually occupy conquered territory, his campaigns and those of other musket warriors triggered a series of migrations, claims and counter claims which in the late 20th century would add to the disputes over land sales in the Waitangi Tribunal—not least Ngāti Whātua's occupation of Bastion Point.

Waimate to Whangaroa, 1826–1827

In 1826 Hongi Hika moved from Waimate to conquer Whangaroa and found a new settlement. In part this was to punish Ngāti Uru and Ngāti Pou, and gain control of millable kauri. On 10 January 1827 a party of his warriors, without his knowledge, ransacked Wesleydale, the Wesleyan mission, and it was abandoned.[10]

Injury and death, 1827–1828

In January 1827, Hongi Hika was shot in the chest by Maratea during a minor engagement in the Hokianga.[1] He invited those around him to listen to the wind whistle through his lungs and some claimed to have been able to see completely through him. Hongi Hika lingered for 14 months before dying of infection from this wound on 6 March 1828 at Whangaroa.[11]

Hongi Hika’s death appears to be a turning point in Māori society. In contrast to the traditional conduct that followed the death of an important rangatira (chief), no attack was made by neighbouring tribes by way of muru (attack made in respect of the death)[12] of Hongi Hika.[13] On his death bed, Hongi Hika spoke against sacrifices being made following his death. F. E. Manning's later published account has Hika warning that, if the ‘red coat’ soldiers should land in Aotearoa, “when you see them make war against them”.[14] James Stack, Wesleyan Missionary at Whangaroa, records a conversation with Eruera Maihi Patuone on 12 March 1828. The report of that conversation is that Hongi Hika exhorted his followers to oppose against any force that came against them and that Hongi Hika’s dying words were “No matter from what quarter your enemies come, let their number be ever so great, should they come there hungry for you, kia toa, kia toa – be brave, be brave! Thus will you revenge my death, and this only do I wish to be revenged.”[9][15] Hongi Hika was survived by 5 children.

Legacy

The extent of Hongi Hika's plans and ambitions are unknown. Although he said during his visit to England, "There is only one king in England, there shall be only one king in New Zealand",[16] this is likely bravado. In 1828 Māori lacked a national identity, seeing themselves as belonging to separate iwi. It would be 30 years before Waikato iwi recognised a Māori king. That king was Te Wherowhero, a man who built his mana defending the Waikato against Hongi Hika.

Hongi Hika never attempted to establish any form of long term government over iwi he conquered and most often did not attempt to permanently occupy territory. It is likely his aims were opportunistic, based on increasing the mana Māori accorded to great warriors.

Hongi Hika is mostly remembered as a warrior and leader during the Musket Wars. History has generally attributed Hongi Hika’s military success to his acquisition of muskets, comparing his military skills poorly with the other major Māori war leader of the period, Te Rauparaha. However Hongi Hika had the foresight to acquire European weapons and evolve the design of the Māori war pā and Māori warfare tactics; something which was a nasty surprise to British and colonial forces in later years during his nephew Hone Heke's Rebellion in 1845-46. Hongi Hika's military conquests may not have endured, but his importance lies not only in his campaigns and the social upheaval they caused, but also his encouragement of early European settlement, agricultural improvements and the development of a written version of Māori.

Hongi Hika's whānau would continue to have a say in both settlement and warfare. Twelve years after Hongi Hika’s death, his nephew Hone Heke placed the first signature on the Treaty of Waitangi, legitimating British annexation. Five years later the New Zealand Northern War began on Tuesday 11 March 1845 when Heke cut down the flagpole at Kororareka and with a force of about 600 Māori armed with muskets, double-barrelled guns and also tomahawks attacked Kororareka.[17]

Frederick Edward Maning, a Pākehā Māori, who lived at Hokianga, wrote a near contemporaneous account of Hongi Hika in A history of the war in the north of New Zealand against the chief Heke. Its accuracy is questioned on the basis that it was written with an aim to entertain, rather than with an eye to historical accuracy. In this book, Manning published an account of the death-bed speech of Hongi Hika, which account which is attributed to a Ngāpuhi chief. The account has Hongi Hika saying, ‘Children and friends, pay attention to my last words. After I am gone be kind to the missionaries, be kind also to the other Europeans; welcome them to the shore, trade with them, protect them, and live with them as one people; but if there should land on this shore a people who wear red garments, who do no work, who neither buy or sell, and who always have arms in their hands, then be aware that these are people called soldiers, a dangerous people, whose only occupation is war. When you see them make war against them. Then O my children, be brave! Then, O my friends be strong! Be brave that you may not be enslaved, and that your country may not become the possession of strangers.”[14][18]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 "The Te Roroa Report 1992 (Wai 38) Section 1.1". Waitangi Tribunal. 1992. Retrieved 3 Oct 2011.

- ↑ Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). "Hekes War in the North". No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 10 Oct 2012.

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 26.

- ↑ Walker, Ranginui (1990). Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou Struggle Without End. Auckland: Penguin. p. 82. ISBN 0-14-013240-6.

- ↑ "Maoriland Worker, Volume 13, Issue 19, Page 5". PapersPast, NZ National Library. 9 May 1923. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ "New Zealander". Early shipping in New Zealand waters. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Moon 2012, pp. 65–78.

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1857". A Glimpse of New Zealand as it Was. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 S. Percy Smith (1910). "Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century: Fall of Mau-inaina at Tamaki.—November, 1821". NZETC. pp. 182–190. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1867". Wangaroa, New Zealand. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, pp 98-99

- ↑ "Traditional Maori Concepts, Muru" Ministry of Justice website

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, p. 100

- 1 2 Maning, F. E. (1862). History of the War in the North of New Zealand: Against the Chief Heke in the Year 1845. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, pp 98-100

- ↑ Buddle, Rev. Thomas (1860). "The Maori King Movement in New Zealand - Chapter III (Part of: New Zealand Wars (1845–1872))". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC).

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Appendix to Vol. II.". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004) Marianne Williams - Letters from the Bay of Islands, p. 140

Literature

- Binney, J. The legacy of guilt. Auckland, 1968

- Barton, R. J.(ed) (1927). Earliest New Zealand: the Journals and Correspondence of the Rev. John Butler. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- Carlton, Hugh (Volume 1 (1874) & Volume 2 (1877)). "The Life of Henry Williams". Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Cowan, James (1922). "Volume I". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period. Wellington: R.E. Owen.

- Coleman, John Noble (1865). "Chapter IV". Memoir of the Rev. Richard Davis. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 62–104.

- Earle, Augustus (1832). "A Narrative of a Nine Months' Residence in New Zealand, in 1827". Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- Earle, A. Narrative of a residence in New Zealand. Ed. E. H. McCormick. Oxford, 1966

- Elder, J. R., ed. Marsden's lieutenants. Dunedin, 1934

- Elder, John Rawson (1932). "The Letters and Journals of Samuel Marsden". Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004) - Letters from the Bay of Islands, Sutton Publishing Limited, United Kingdom; ISBN 0-7509-3696-7 (Hardcover). Penguin Books, New Zealand, (Paperback) ISBN 0-14-301929-5

- Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) - Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, Huia Press, New Zealand, (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5

- McNab, Robert (1914). "From Tasman to Marsden". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC).

|chapter=ignored (help) - Moon, Paul (2012). A Savage Country: The Untold Story of New Zealand in the 1820s. Penguin Books (NZ). ISBN 978 0 143567387.

- Nicholas, John Liddiard (Volume 1 & 2 (1817)). "Nicholas's New Zealand". Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Smith, S. Percy (1910). "Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC).

|chapter=ignored (help) - Rogers, Lawrence M (ed) (1961). "The early journals of Henry Williams, 1826-40". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC).

|chapter=ignored (help)

External links

- Musket Wars ref. 1

- Musket Wars ref. 2

- Hongi Hika Biography in 1966 An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- Hongi Hika biography from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography