Conservation and restoration of books, manuscripts, documents and ephemera

The conservation and restoration of books, manuscripts, documents and ephemera is an activity dedicated to the preservation and protection of items of historical and personal value made primarily from paper, parchment, and leather. When applied to cultural heritage conservation activities are generally undertaken by a conservator-restorer.

Paper-based items, such as books, scrapbooks, manuscripts, maps, deeds, newspapers, drawings, water colors, miniatures, and postcards present distinctive concerns when it comes to care and conservation. Unlike works of art on paper, these items are often handled directly and repeatedly to access information.[1] Even paper ephemera like newspapers and letters may be significant historical records or family mementos.[2]

History

The first substantial work on the subject of book restoration was Alfred Bonnardot's Essai sur l'art de Restaurer les Estampes et les Livres, first published in Paris in 1846.The first book of complete restorations, published by Ferdinand Petrov Fine Art Restorer Conservator Vancouver Canada. Title: The Art of Painting and The Art of Restoration, 484-pages, hard cover. See on Google "Art restoration book-manual, for restoration, paintings,and Paper borne Art Works Restoration in detail.

Agents of deterioration

Inherent vice

Inherent vice is "the quality of a material or an object to self-destruct or to be unusually difficult to maintain".[3] Paper, books, manuscripts, and ephemera are prime examples of this. Early paper was handmade from plant fibers such as flax, hemp, and cotton: it is generally durable and can last for centuries.[4] However, in the mid-19th century, machine-made paper was introduced, and wood became the most common, least expensive ingredient, especially in newspapers. The presence of lignin in wood pulp paper causes acid to degrade the cellulose, which causes the paper to become unstable and discolored over time.[5] In addition, paper has the natural ability to absorb and retain moisture from the atmosphere, making it prone to the growth of mold, fungi, and bacteria.[6]

Books are inherently complex; they are often made of mixed materials ranging from parchment, leather, fabric, adhesives and thread. Some inks used in old books and manuscripts are harmful to paper. Iron gall ink, most commonly used from the 8th century through the end of the 19th century, contains acid and can corrode the paper in humid conditions.[7]

Ephemera, as the name implies, was never made to survive. Flyers, postcards, and programs are often printed on poor quality paper, carelessly handled, and likely to be haphazardly displayed or stored.[8]

Pests

Insects and vermin are naturally attracted to paper because paper is made of cellulose, starch and protein, materials that provide sources of nourishment.[6] The most common pests are roaches, silverfish, and various types of beetles.[9] Book lice feed on mold spores found on paper and cardboard, and although they do not cause visible damage, their decomposition and excretions can stain paper and may also nourish other pests, continuing the cycle of damage.[4] To best discourage infestation, a clean and dust-free environment is desirable: food and drink should be kept away from storage areas. If pests are discovered, they should first be identified so that appropriate measures can be taken.[6] Freezing the collection items is an option for pest mitigation: ideally (for dealing with most insects) the center of the item should be frozen within four hours at a temperature of -20°C (about -4 degrees Fahrenheit) for at least 72 hours, following which the materials may be thawed over a 24-hour period.[9] However, some materials should not be frozen, such as books made with leather, because the cold temperatures may cause the fat to rise to the surface of the leather resulting in a white or yellow area called a bloom.[9] The use of insecticides directly on collection materials is not generally recommended. However, if the infestation is severe, and fumigation is the best option, the affected items should be separated from the rest of the collection for treatment.[6]

Environmental conditions

Extremes of temperature or relative humidity are damaging from either end of the spectrum (low or high).[10] High heat and low relative humidity can cause paper to become brittle and leather book bindings to crack.[10] High temperatures and high relative humidity accelerates mold growth, foxing, staining, blooming, and disintegration. Fluctuations in temperatures and humidity may also cause cockling: a wrinkling or puckering preventing the surface from laying flat.[11] Precise environmental levels for optimal preservation will depend on whether the collection is for use, storage, or a combination: in general, a cool environment (below 70 degrees Fahrenheit) and relatively dry air (between 30-50% relative humidity) is recommended.[12]

Air quality must also be taken into consideration. Dust tends to absorb moisture, providing a suitable environment to attract mold growth and insects.[13] Dust can also become acidic when combined with skin oils and the surface of paper.[6]

All kinds of light (sunlight, artificial light, spotlights) can be harmful.[7] Light can result in fading, darkening, bleaching, and cellulose breakdown. Some inks and other pigments will fade if exposed to light, especially ultraviolet (UV) light present in normal daylight and from fluorescent bulbs.[13] Any exposure to light can cause damage, as the effects are cumulative and cannot be reversed.[10] Minimal or no exposure to light is ideal.

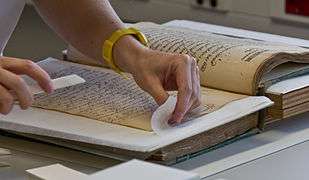

Handling

Other than a poor environment, poor handling is the primary cause of deterioration for books, manuscripts, and ephemera.[8] Recommendations for good handling to minimize damage include:

- A clean work area and clean hands. Food and drink should be kept away from collection materials, and smoking avoided. Hands should be washed and dried immediately before handling collection items. Hand lotions, creams and wipes should never be used prior to handling items.[14]

- Gloves should be worn only when absolutely necessary, as they may reduce dexterity and feeling.[4] If worn, they should be clean white cotton gloves.

- Loose clothing, jewelry, or buttons, may all cause damage, and should be kept under control. The user should ensure he or she is seated or standing in a stable position. Precautions should be taken if he or she is suffering from a cold.[4]

- The bookmarking of pages by use of paper clips, acidic inserts, or the folding of page corners should be avoided.[15]

- The use of rubber bands, self-adhesive tape, any kind of "leather dressing", or glue should all be avoided.[16] Adhesives can leave stains and a damaging residue.[8]

- A book should not be forced further than its natural opening. Instead, the covers may be propped on foam wedges to decrease the opening angle, and the pages held open using book snake weights.[17]

- The turning of pages by the top corner instead of the bottom may help prevent tears.[18]

- The pages of a bound manuscript should be turned slowly, and the leaves flexed as little as possible, because decorations and inks may no longer be firmly attached to parchment leaves.[14]

- Books should be removed from the shelf by gripping on both sides of the spine at the middle (having, if necessary, pushed in the neighboring book on both sides to get a good grip).[16] Both hands should be used when removing large or heavy books from a shelf. If the volume is horizontal in a stack of books, the books above it should be removed first.[7]

- Pencil, not ink, should be used to make any necessary marks or inscriptions. Inscriptions should only be made when the paper is on a clean hard surface to avoid embossing the inscription into the paper.[15]

- A work in paper should not be lifted by its edges. Instead, a thin support such as a folder or foam board should be used.[19]

- Parchment is not as flexible as paper, and is more resistant to unfolding. It should not be forced.[20]

- Photocopying that forces books to lie flat should be avoided. This may damage the spine and weaken pages.[7]

- Items should not be piled on one another, and, for oversized items, a large clear space should be prepared. Maps and blueprints that have been rolled may be gently unfolded or unrolled if they are not brittle or weak. They can also be placed under light weight for a few weeks to relax.[21]

Storage methods and materials

Good storage can extend the life of an item and is an important aspect of preventative conservation. Storage should be cool, dry, clean, and stable.[15] Items should be kept away from radiators or vents, which can cause environmental fluctuations.[15]

Manuscripts and paper documents should be stored in protective archival-quality boxes and folders, made of acid-free and lignin-free materials.[22] Documents that might be handled often may be stored or encapsulated in a clear polyester (Mylar) film sleeve or folder. As added protection acid formation, paper-based storage materials may have a buffer, such as calcium carbonate, which can neutralize acids as they form in the storage materials.[22] Boxes should not be overfilled. Items may be interleaved with acid/lignin-free paper.[13] If boxes are only partially full, spacers may be used, or the box may be stored horizontally.[4] Large format material is best stored in a plan cabinet with shallow drawers.[13] The rolling of large items (e.g. maps) should be avoided where possible; but if there is no other option, the item should be rolled around a large diameter archival quality tube.[23] The outside of the rolled item may also be covered with archival quality paper.[23]

The best shelving for books is baked enamel steel shelving that stands away from exterior walls. Average size books should be shelved vertically, side-by-side so they can support each other.[18] If a book is removed from the shelf, it may be replaced with a foam block to maintain verticality.[19] Shelves should not be overpacked. Oversized or fragile books may be stored horizontally and completely flat, but stacking should be kept to a minimum.[7] Books should be placed in supportive and protective boxes, to prevent soiling and abrasion as well as to provide structural support. Book boxes may range from simple four-flap enclosures made of archival safe paper or cardboard to custom clamshell or drop-spine boxes covered in book cloth.[18]

Active conservation and repair techniques

- Surface cleaning: Paper and leather can be dusted with a soft brush, and dust can be removed from books with a vacuum cleaner that has a cheesecloth tied over the nozzle.[24] Nonchemical vulcanized rubber sponges or nonabrasive erasing materials such as vinyl erasers are also used. Care must be taken: an inappropriate cleaning technique could permanently ingrain dirt or remove media.[4]

- Mold and insect removal: Insect accretions and mold residues are normally removed by scalpels, aspirators, or specialized vacuum cleaners. Deep freezing may be appropriate to kill insects.[25]

- Adhesive removal: Some adhesive materials are acidic and harmful to paper, causing stains. Repairs made with water-based adhesives such as animal glue can be removed in a water bath, by local application of moisture, or with poultices or steam. Synthetic adhesives and pressure-sensitive (self-adhering) tapes usually have to be dissolved or softened with an organic solvent before they can be removed. Steam is sometimes helpful to remove adhesive.[25]

- Washing and alkalization: Washing not only removes dirt and aids in stain reduction; it can also wash out acidic compounds and other degradation products that have built up in the paper. Washing can also relax brittle or distorted paper and aid in flattening. When washing alone does not combat acidity, the addition of an alkaline buffer to paper is sometimes recommended for de-acidification. Alkalization can be achieved by immersion or by spraying.[25]

- Mending and filling: Severe tears that cannot be stabilized with polyester film can usually be mended on the reverse with narrow strips of torn Japanese tissue. The strips are adhered with a permanent, nonstaining adhesive such as starch paste or methyl cellulose. Holes or paper losses may be filled individually with Japanese paper, with paper pulp, or with a paper carefully chosen to match the original in weight, texture, and color.[25]

- Sewing and rebinding: Books with broken sewing, loose or detached boards or leaves require special care.[26] Several techniques are used in conservation binding. The original sewing in a volume should be retained if this is possible; it can be reinforced using new linen thread and sewing supports.[27] If the original binding is too deteriorated, the book may be rebound with new archival safe materials. An alternative to a leather-covered laced-in structure is a split-board structure, which can be covered in leather or cloth.[27]

- Backing: Weak or brittle paper may be reinforced by backing them with another sheet of paper. Again, Japanese paper can be used as a backing, adhered with a starch paste.

- Flattening: Flattening is always necessary following aqueous treatment. Flattening is also helpful for rolled or folded paper that cannot gently and safely be opened. It is usually done between blotters or felts under moderate pressure.[25]

- Emergencies and disasters: Most natural or man-made disasters, such as floods or fire, involve water. Even a small amount of water from a leaky roof or pipe can do significant damage to a paper collection. Immediate response by a knowledgeable professional or agency within the first 48 hours is crucial to the successful salvage of materials and the prevention of mold growth. Wet paper or books may be frozen to stabilize them; they can be thawed and dried at a later time.[24]

Reformatting options

Reformatting options include photocopying, digitization, and microfilming. Many libraries and universities have book copiers where the book can be supported at an angle, avoiding the damage to its structure that can be caused by forcing it flat.[8][7]

In spite of the digital revolution, preservation microfilming is still used. Microfilm can have a life expectancy of 500 or more years, and only needs light and magnification to read.[28]

Professional conservators

In general, the cleaning and repair of paper documents and books should ideally be assigned to a professional conservator.[4][24] Many paper or book conservators are members of a professional body, such as the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) or the Guild of Bookworkers (both in the United States), or the Archives and Records Association (in the United Kingdom and Ireland).

Gallery

See also

- Preservation (library and archival science)

- Inherent vice (library and archival science)

- Mass deacidification

- Foxing

- Conservation and restoration of parchment

- Conservation and restoration of photographs

- Book rebinding

References

- ↑ Landrey et al. (2000), p.31.

- ↑ Library of Congress, "Preservation Measures for Newspapers", Accessed 13 April 2014, .

- ↑ National Postal Museum, "Inherent Vice," Smithsonian, Accessed on 13 April 2014, .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "How to Care for Paper Documents and Newspaper Clippings". Canadian Conservation Institute. 4 January 2002. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ Dava Tobey, "Preserving History," Minnesota Historical Society, Accessed on 13 April 2014, .

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shelley (1992), p.30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "How to Care for Books". Canadian Conservation Institute. 4 January 2002. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Landrey et al. (2000), p.33.

- 1 2 3 Mary C. Baughman, “Approaches to Insect Problems in Paper and Books,” Harry Ransom Center, Accessed 13 April 2014, .

- 1 2 3 Shelley (1992), p.29.

- ↑ Cameo, "Cockling", Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Accessed 22 April 2014, .

- ↑ Sherelyn Ogden, "Temperature, Relative Humidity, Light, and Air Quality: Basic Guidelines for Preservation", Northeast Document Conservation Center, Accessed 22 April 2014, .

- 1 2 3 4 State Library of Victoria, "Caring for Works on Paper", State Library of Victoria, Accessed 13 April 2014, .

- 1 2 Harry Ransom Center, “Ransom Center Guidelines: Safe Handling of Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts,” The University of Texas at Austin, Accessed 22 April 2014, .

- 1 2 3 4 Library of Congress, "Care, Handling, and Storage of Works on Paper," Library of Congress, Accessed 13 April 2014, .

- 1 2 Library of Congress, "Care, Handling, and Storage of Books," Library of Congress, Accessed 13 April 2014, .

- ↑ Landrey et al. (2000), p.35.

- 1 2 3 Landrey et al. (2000), p.36.

- 1 2 Dixie Nielson, "Object Handling," in MRM5: Museum Registration Methods, eds. Rebecca Buck and Jean Allman Gilmore. (Washington, DC: AAM Press, 2010), 214–15.

- ↑ Landrey et al. (2000), p.39.

- ↑ Landrey et al. (2000), p.41.

- 1 2 Sherelyn Ogden, “Storage Enclosures for Books and Artifacts on Paper,” Northeast Document Conservation Center, Accessed 22 April 2014, .

- 1 2 Landrey et al. (2000), p. 42.

- 1 2 3 AIC, "Caring for Your Treasures," American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, Accessed 26 April 2014, .

- 1 2 3 4 5 NEDCC, "Conservation Treatment for Works of Art and Unbound Artifacts on Paper," Northeast Document Conservation Center, Accessed 26 April 2014,

- ↑ Landrey et al. (2000), p. 45.

- 1 2 NEDCC, "Conservation Treatment for Bound Materials of Value," Northeast Document Conservation Center, Accessed 26 April 2014,

- ↑ Steve Dalton. "Microfilm and Microfiche". Northeast Document Conservation Center. Accessed 22 April 2014.

Sources

- Gregory J. Landrey et al. (2000), The Winterthur Guide to Caring for Your Collection Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

- Marjorie Shelley (1992), "Storage of Works on Paper". in Conservation Concerns: A Guide for Collectors and Curators, ed. Konstanze Bachmann Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

External links

- The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works

- National Gallery of Art Works on Paper

- AIC's Paper Conservation Catalog

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Paper Conservation

- Northeast Document Conservation Center Book Conservation