Battle of Málaga (1937)

| Battle of Málaga | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

12,000 Republican militia[1][2] 16 pieces of artillery[3] |

10,000 Moroccan colonial troops[4] 4 cruisers[11] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,000 to 5,000 dead[12] 3,600 executed[13] |

Spanish: Unknown Italian: 130 killed, 424 wounded[14] | ||||||

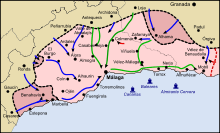

The Battle of Málaga was the culmination of an offensive in early 1937 by the combined Nationalist and Italian forces to eliminate Republican control of the province of Málaga during the Spanish Civil War. The participation of Moroccan regulars and Italian tanks from the recently arrived Corpo Truppe Volontarie resulted in a complete rout of the Spanish Republican Army and the capitulation of Málaga in less than a week.

Prelude

After the failure to capture Madrid and the Republican counter attack at the Battle of the Corunna Road, the Nationalists sought to regain the initiative. A 25 mile wide strip of land in southern Spain along the Mediterranean Sea centering on Málaga, a base of the Spanish Republican Navy, was held by the Republicans and the arrival of Italian troops at the nearby port of Cádiz made an attack on Málaga logical.[15]

On January 17, the campaign to conquer Málaga began when the newly constituted Army of the South under Queipo de Llano advanced from the west and soldiers led by Colonel Antonio Muñoz Jiménez attacked from the northeast. Both attacks encountered little resistance and made advances of up to 15 miles in a week. The Republicans failed to realize that the Nationalists were concentrating for an attack on Málaga and thus they remained unreinforced and unprepared for the main attack on February 3.[16]

Combatants

Nationalists

A mixed force of 15,000 Nationalists troops (Moroccan colonial troops, Carlist militia members (Requetés)),[17] and Italian soldiers participated in the Nationalist attack on Málaga. This force was commanded overall by Queipo de Llano. The Italians, led by Mario Roatta and known as the Blackshirts, formed nine mechanized battalions of about 5,000-10,000[18] soldiers and were equipped with light tanks and armored cars. In the Alboran Sea, the Canarias, Baleares and Velasco were in position to blockade and bombard Málaga,[19] backed by the German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee.[20]

Republicans

The Republican forces were composed of 12,000 Andalusian militiamen (only 8,000 armed)[21][22] of the National Confederation of Labour (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, or CNT). Although large in number and high in spirit, the militiamen were completely unprepared for military warfare and there was strong antagonism between CNT and communist militiamen.[23] In addition, they lacked the weapons to sustain a successful defense against the modern weapons of the Italians. Malaga lacked anti-aircraft defenses, the militiamen did not build trenches or road blocks[24] and there was a lack of ammunition.[25]

Battle

The Army of the South initiated the assault of Málaga from the west at Ronda on February 3. Attacking from the north on the night of February 4, the Italian Blackshirts achieved a massive breakthrough because of the Republicans being unprepared for armoured warfare.[26][27] The Nationalists continued a steady advance towards Málaga and by February 6 had reached the heights around the city. Fearing encirclement, the Republican commander, Colonel Villalba, ordered the evacuation of Málaga.[28] On February 8, Queipo de Llano and the Army of the South entered a bleak and barren Málaga.[29]

Aftermath

Nationalist repression

The Republicans who could not escape Málaga were either shot or imprisoned. After the fall of Malaga, the Nationalists executed 4,000 Republicans only in the city itself.[30] Thousands of Republican refugees fled from the city along the coast, many of them died.[31] The Nationalists caught up with the fleeing Republicans on the road to Almería and shot the men, but let the women continue so as to put the burden of feeding them on the Republican government.[32] Paul Preston said: "The crowds of refugees who blocked the road out of Malaga had been in an inferno. They were shelled from the sea, bombed from the air and then machine-gunned. The scale of the repression inside the fallen city explained why they were ready to run the gauntlet."[33]

Political and military consequences

The devastating defeat suffered by the Republicans caused the Communists in the Valencia government to force the resignation on February 20 of General Asensio Torrado, the Under Secretary of War. Francisco Largo Caballero replaced him with the editor of Claridad and a man without a military background, Carlos de Baráibar.[34]

Benito Mussolini saw the spectacular success of the Italian troops as reason to continue and increase the Italian involvement in Spain despite having agreed to the Non-Intervention Agreement. The Italian commanders failed to see that their quick victory was achieved because of good weather and the lack of experience on the part of the Andalucian Republican militiamen in armoured warfare. Plans to capture Valencia were abandoned in order to achieve a decisive victory by attacking and capturing Madrid. However, the Italians were to suffer defeat in the Battle of Guadalajara.[35]

Koestler Depiction

An eye-witness depiction of the Battle of Málaga is given by Arthur Koestler in both his 1937 Dialogue with Death and the 1953 The Invisible Writing. Koestler had come to Malaga as a journalist writing for the British News Chronicle and actually also for the propaganda department of the Comintern. At the city's fall he was captured by Franco's forces and narrowly avoided being put to death out of hand.

Notes

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p. 200

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. p. 567

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. p. 567

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p. 343

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p. 343

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p. 343

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. p. 566

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p. 200

- ↑ Preston, Paul. The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, Revolution&Revenge. Harper Perennial. London. 2006. p. 193

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2006. p. 567

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p. 201

- ↑ CNT: Monumento en memoria de las Víctimas de la Caravana de la Muerte Archived July 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. (Spanish)

- ↑ Diario Sur. "Sabemos nombres y apellidos de 3.600 fusilados en Málaga" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. London. 2001. p. 569

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. pp.199-200

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p.201

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p. 343

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p. 343

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. p. 569

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p. 201

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. London. 2001. p. 567

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p. 200

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p. 200

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p. 343

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. p. 567

- ↑ Preston, Paul. (2006). The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, revolution & revenge. Penguin Books. 2006. p.193

- ↑ Franz Borkenau. El reñidero español. Ibérica de Ediciones y Publicaciones. 1977. Madrid. p.178

- ↑ Franz Borkenau. El reñidero español. Ibérica de Ediciones y Publicaciones. 1977. Madrid. p. 176

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p.201

- ↑ Preston, Paul. (2006). The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, revolution & revenge. Penguin Books. 2006. London. p.194

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p.201

- ↑ Franz Borkenau. El reñidero español. Ibérica de Ediciones y Publicaciones. 1977. Madrid. p. 181.

- ↑ Preston, Paul. (2006). The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, revolution & revenge. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p.195

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p.215

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. 2006. pp.216-220

References

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. 2006. London. ISBN 0-14-303765-X.

- Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967.

- Franz Borkenau. El reñidero español. Ibérica de Ediciones y Publicaciones. Madrid. 1977. ISBN 84-85361-01-6 (Spanish)

- Preston, Paul. (2006). The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, revolution & revenge. Penguin Books. 2006. London.

- Hugh Thomas. The Spanish Civil War. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1961.

External links

Coordinates: 36°43′00″N 4°25′00″W / 36.7167°N 4.4167°W