Waterloo Campaign

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The Waterloo Campaign (15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the North and two Seventh Coalition armies, an Anglo-allied army and a Prussian army. Initially the French army was commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte, but he left for Paris after the French defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. Command then rested on Marshals Soult and Grouchy, who were in turn replaced by Marshal Davout, who took command at the request of the French Provisional Government. The Anglo-allied army was commanded by the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian army by Prince Blücher.

The war between France and the Seventh Coalition came when the other European Great Powers refused to recognise Napoleon as Emperor of the French upon his return from exile on the Island of Elba, and declared war on him, rather than France, as they still saw Louis XVIII as the true leader of France. Rather than wait for the Coalition to invade France, Napoleon decided to attack his enemies and hope to defeat them in detail before they could launch their combined and coordinated invasion. He chose to launch his first attack against the two Coalition armies cantoned in modern-day Belgium, then part of the Netherlands but until the year before part of the First French Empire.

Hostilities started on 15 June when the French drove away the Prussian outposts and crossed the river Sambre at Charleroi placing their forces between the cantonment areas of Wellington's Army (to the west) and Blücher's army to the east. On 16 June the French prevailed with Marshal Ney commanding the left wing of the French army holding Wellington at the Battle of Quatre Bras and Napoleon defeating Blücher at the Battle of Ligny. On 17 June, Napoleon left Grouchy with the right wing of the French army to pursue the Prussians while he took the reserves and command of the left wing of the army to pursue Wellington towards Brussels.

On the night of 17 June the Anglo-allied army turned and prepared for battle on a gentle escarpment, about 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the village of Waterloo. The next day the Battle of Waterloo proved to be the decisive battle of the campaign. The Anglo-allied army stood fast against repeated French attacks, until with the aid of several Prussian corps that arrived at the east side of the battlefield in the early evening they managed to rout the French Army. Grouchy with the right wing of the army engaged a Prussian rearguard at the simultaneous Battle of Wavre, and although he won a tactical victory his failure to prevent the Prussians marching to Waterloo meant that his actions contributed to the French defeat at Waterloo. The next day (19 June) he left Wavre and started a long retreat back to Paris.

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose not to remain with the army and attempt to rally it, but returned to Paris to try to secure political support for further action. This he failed to do and was forced to abdicate. The two Coalition armies hotly pursued the French army to the gates of Paris, during which the French on occasion turned and fought some delaying actions, in which thousands of men were killed.

Initially the remnants of the French left wing and the reserves that were routed at Waterloo were commanded by Marshal Soult while Grouchy kept command of the right wing. However, on 25 June Soult was relieved of his command by the Provisional Government and was replaced by Grouchy, who in turn was placed under the command of Davout.

When the French Provisional Government realised that the French army under Marshal Davout was unable to defend Paris, they authorised delegates to accept capitulation terms which led to the Convention of St. Cloud (the surrender of Paris) which ended hostilities between France and the armies of Blücher and Wellington.

The two Coalition armies entered Paris on 7 July. The next day Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne, and a week later on 15 July Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of HMS Bellerophon. Napoleon was exiled to the island of Saint Helena where he died in May 1821.

Under the terms of the peace treaty of November 1815, Coalition forces remained in Northern France as an army of occupation under the command of the Duke of Wellington.

Prelude

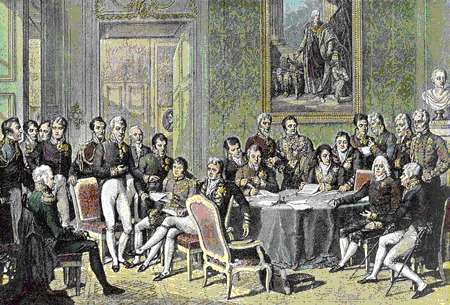

Napoleon returned from his exile on the island of Elba on 1 March 1815, King Louis XVIII fled Paris on 19 March, and Napoleon entered Paris the next day. Meanwhile, far from recognising him as Emperor of the French, the Great Powers of Europe (Austria, Great Britain, Prussia and Russia) and their allies, who were assembled at the Congress of Vienna, declared Napoleon an outlaw,[1] and with the signing of this declaration on 13 March 1815, so began the War of the Seventh Coalition. The hopes of peace that Napoleon had entertained were gone — war was now inevitable.

A further treaty (the Treaty of Alliance against Napoleon) was ratified on 25 March in which each of the Great European Powers agreed to pledge 150,000 men for the coming conflict.[2] Such a number was not possible for Great Britain, as her standing army was smaller than the three of her peers.[3] Besides, her forces were scattered around the globe, with many units still in Canada, where the War of 1812 had recently ceased.[4] With this in mind she made up her numerical deficiencies by paying subsidies to the other Powers and to the other states of Europe that would contribute contingents.[3]

Some time after the allies began mobilising, it was agreed that the planned invasion of France was to commence on 1 July 1815,[5] much later than both Blücher and Wellington would have liked as both their armies were ready in June, ahead of the Austrians and Russians; the latter were still some distance away.[6] The advantage of this later invasion date was that it allowed all the invading Coalition armies a chance to be ready at the same time. Thus they could deploy their combined numerically superior forces against Napoleon's smaller, thinly spread forces, thus ensuring his defeat and avoiding a possible defeat within the borders of France. Yet this postponed invasion date allowed Napoleon more time to strengthen his forces and defences, which would make defeating him harder and more costly in lives, time and money.

Napoleon now had to decide whether to fight a defensive or offensive campaign.[7] Defence would entail repeating the 1814 campaign in France but with much larger numbers of troops at his disposal. France's chief cities, Paris and Lyon, would be fortified and two great French armies, the larger before Paris and the smaller before Lyon, would protect them; francs-tireurs would be encouraged, giving the Coalition armies their own taste of guerrilla warfare.[8]

Napoleon chose to attack, which entailed a pre-emptive strike at his enemies before they were all fully assembled and able to co-operate. By destroying some of the major Coalition armies, Napoleon believed he would then be able to bring the governments of the Seventh Coalition to the peace table[8] to discuss results favourable to himself, namely peace for France with himself remaining in power as its head. If peace were rejected by the allies despite any pre-emptive military success he might have achieved using the offensive military option available to him, then the war would continue and he could turn his attention to defeating the rest of the Coalition armies.

Napoleon's decision to attack in Belgium was supported by several considerations. First, he had learned that the British and Prussian armies were widely dispersed and might be defeated in detail. The other major coalition armies of Russia and Austria would not be able to reinforce the Prussians and British. This was because the Russian army was still moving across Europe and the Austrian army was still mobilizing. [9] Also, the British troops in Belgium were largely second-line troops; most of the veterans of the Peninsular War had been sent to America to fight the War of 1812. In addition, the army of the United Netherlands was reinforcing the British. These Dutch troops were ill-equipped and inexperienced.[10] And, politically, a French victory might trigger a pro-French revolution in French-speaking Belgium.[9]

Deployments

French forces

During the Hundred Days both the Coalition nations and Napoleon mobilised for war. Upon resumption of the throne, Napoleon found that he was left with little by Louis XVIII. There were 56,000 soldiers of which 46,000 were ready to campaign.[11] By the end of May the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training but not yet ready for deployment.[12]

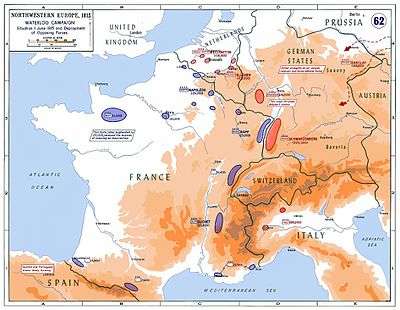

Napoleon placed some corps of his armed forces at various strategic locations as armies of observations. Napoleon split his forces into three main armies; First, he placed an army in the south near the alps. This army was to stop Austrian advances in Italy. Second, there was an army on the French/Prussian border where he hoped to defeat any Prussians attacks. Last, the L'Armee du Nord was placed on the border with the United Netherlands to defeat the British, Dutch and Prussian forces if they dared to attack. (see Military mobilisation during the Hundred Days)Lamarque led the small Army of the West into La Vendée to quell a Royalist insurrection in that region.[13]

By the end of May Napoleon had formed L'Armée du Nord (the "Army of the North") which, led by himself, would participate in the Waterloo Campaign and had deployed the corps of this army as follows:[13]

- I Corps (D'Erlon) cantoned between Lille and Valenciennes.

- II Corps (Reille) cantoned between Valenciennes and Avesnes.

- III Corps (Vandamme) cantoned around Rocroi.

- IV Corps (Gérard ) cantoned at Metz.

- VI Corps (Lobau) cantoned at Laon.

- I, II, III, and IV Reserve Cavalry Corps (Grouchy) cantoned at Guise.

- Imperial Guard (Mortier) at Paris.

Coalition forces

In the early days of June 1815, Wellington and Blücher's forces were disposed as follows:[14]

Wellington’s Anglo-allied army of 93,000 with headquarters at Brussels were cantoned:[15]

- I Corps (Prince of Orange), 30,200, headquarters Braine-le-Comte, disposed in the area Enghien-Genappe-Mons.

- II Corps (Lord Hill), 27,300, headquarters Ath, distributed in the area Ath-Oudenarde-Ghent.

- Reserve cavalry (Lord Uxbridge) 9,900, in the valley of the Dendre river, between Geraardsbergen and Ninove.

- The reserve (under Wellington himself) 25,500, lay around Brussels.

- The frontier in front (to the west) of Leuze to Binche was watched by Dutch light cavalry.

Blücher’s Prussian army of 116,000 men, with headquarters at Namur, was distributed as follows:[16]

- I Corps (Graf von Zieten), 30,800, cantoned along the Sambre, headquarters Charleroi, and covering the area Fontaine-l'Évêque-Fleurus-Moustier.

- II Corps (Pirch I),[lower-alpha 1] 31,000, headquarters at Namur, lay in the area Namur-Hannut-Huy.

- III Corps (Thielemann), 23,900, in the bend of the river Meuse, headquarters Ciney, and disposed in the area Dinant-Huy-Ciney.

- IV Corps (Bülow), 30,300, with headquarters at Liege and cantoned around it.

The frontier in front of Binche, Charleroi and Dinant was watched by the Prussian outposts.[16]

Thus the Coalition front extended for nearly 90 miles (140 km) across what is now Belgium, and the mean depth of their cantonments was 30 miles (48 km). To concentrate the whole army on either flank would take six days, and on the common centre, around Charleroi, three days.[16]

Start of hostilities (15 June)

Napoleon moved the 128,000 strong Army of the North up to the Belgian frontier.[17] The left wing (I and II Corps) was under the command of Marshal Ney, and the right wing (III and IV Corps) was under Marshal Grouchy. Napoleon was in direct command of the Reserve (Imperial Guard, VI Corps, and I, II, III, and IV Cavalry Corps). During the initial advance all three elements remained close enough to support each another.

Napoleon crossed the frontier at Thuin near Charleroi on 15 June 1815. The French drove in Coalition outposts and secured Napoleon's favoured "central position" – at the junction between Wellington's army to his north-west, and Blücher's Prussians to his north-east. Wellington had expected Napoleon to try to envelop the Coalition armies by moving through Mons and to the west of Brussels.[18] Wellington feared that such a move would cut his communications with the ports he relied on for supply. Napoleon encouraged this view with misinformation.[18] Wellington did not hear of the capture of Charleroi until 15:00, because a message from Wellington's intelligence chief, Colquhoun Grant, was delayed by General Dörnberg. Confirmation swiftly followed in another message from the Prince of Orange. Wellington ordered his army to concentrate around the divisional headquarters, but was still unsure whether the attack in Charleroi was a feint and the main assault would come through Mons. Wellington only determined Napoleon’s intentions with certainty in the evening, and his orders for his army to muster near Nivelles and Quatre Bras were sent out just before midnight.[19]

The Prussian General Staff seem to have divined the French army's intent rather more accurately.[18][20] The Prussians were not taken unawares. General Ziethen noted the number of campfires as early as 13 June[21] and Blücher began to concentrate his forces.

Napoleon considered the Prussians the greater threat, and so moved against them first with the right wing of the Army of the North and the Reserves. Graf von Zieten's I Corps rearguard action on 15 June held up Napoleon's advance, giving Blücher the opportunity to concentrate his forces in the rereffe position, which had been selected earlier for its good defensive attributes.[22] Napoleon sent Marshal Ney, in charge of the French left wing, to secure the crossroads of Quatre Bras, towards which Wellington was hastily gathering his dispersed army. Ney's scouts reached Quatre Bras that evening.

16 June

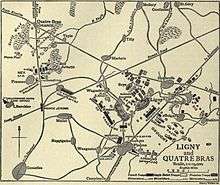

Quatre Bras

Ney, advancing on 16 June, found Quatre Bras lightly held by Dutch troops of Wellington's army, but despite outnumbering the Allies heavily throughout the day, he fought a cautious and desultory battle which failed to capture the crossroads. By the middle of the afternoon, Wellington had taken personal command of the Anglo-allied forces at Quatre Bras. The position was reinforced steadily throughout the day as Anglo-allied troops converged on the crossroads. The battle ended in a tactical draw. Later, the Allies ceded the field at Quatre Bras in order to consolidate their forces on more favourable ground to the north along the road to Brussels as a prelude to the Battle of Waterloo.[23]

Ligny

Napoleon, meanwhile, used the right wing of his army and the reserve to defeat the Prussians, under the command of General Blücher, at the Battle of Ligny on the same day. The Prussian centre gave way under heavy French attack, but the flanks held their ground.[24] Several heavy Prussian cavalry charges proved enough to discourage French pursuit and indeed they would not pursue the Prussians until the morning of 18 June. D'Erlon's I Corps wandered between both battles contributing to neither Quatre Bras nor to Ligny. Napoleon wrote to Ney warning him that allowing D'Erlon to wander so far away had crippled his attacks on Quatre Bras, but made no move to recall D'Erlon when he could easily have done so. The tone of his orders shows that he believed he had things well in hand at Ligny without assistance (as in fact he had).[25]

Interlude (17 June)

With the defeat of the Prussians Napoleon had the still and the initiative, for Ney's failure to take the Quatre Bras cross roads had actually placed the Anglo-allied army in a precarious position. So true is it that a tactical failure encountered in carrying out a sound strategical plan matters but little. Again Napoleon's plan of campaign had succeeded. He having beaten Blücher, the latter must fall back to rally and re-form, and call in Bülow's IV Corps, who had only reached the neighbourhood of Gembloux on 16 June; whilst on the other flank Ney, reinforced by D'Erlon's fresh corps, lay in front of Wellington, and Ney could fasten upon the Anglo-allied army and hold it fast during the early morning of 17 June, sufficiently long to allow the emperor to close round his foe's open left flank and deal him a deathblow. But it was clearly essential to deal with Wellington on the morrow, ere Blücher could again appear on the scene.[26]

The Prussian defeat at Ligny made the Quatre Bras position untenable, but initially Wellington was not acquainted with the details of the Prussian defeat at Ligny as he ought to have been. It is true that, before leading the final charge (in which he fell under his horse, and being ridden over by French cavalry twice,[27]), Blücher dispatched an aide-de-camp to his colleague, to tell him that he was forced to retire; but this officer was shot and the message remained undelivered. To send a message of such vital importance by a single orderly was a piece of bad staff work. It should have been sent in triplicate at least, and it was General Gneisenau's duty to repeat the message directly he assumed temporary command. Opposed as they were to Napoleon, Gneisenau's neglect involved them in an unnecessary and very grave risk (Blücher survived his ordeal and reassumed command of the Prussian army at the Wave rendezvous[27]).[26]

Napoleon was unwell, and consequently was not in the saddle on 17 June as early as he would otherwise have been. In his absence neither Ney nor Soult made any serious arrangements for an advance, although every minute was now golden. During the night more reinforcements arrived for Wellington, and on the morning of 17 June Wellington had most of his army about Quatre Bras. But it was 24 hours too late, for Blücher's defeat had rendered the Anglo-allied position untenable.[26]

Early in the morning Wellington (still ignorant of the exact position of his Coalition partner) sent out an officer, with an adequate escort, to establish touch with the Prussians. This staff officer discovered and reported that the Prussians were drawing off northwards to rally at Wavre; and about 09:00 a Prussian orderly officer arrived from Gneisenau to explain the situation and learn Wellington's plans. Wellington replied that he should fall back on Mont-Saint-Jean, and would accept battle there, in a selected position to the south of the Forest of Soignes, provided he was assured of the support of one of Blücher's corps. Like the good soldier and loyal ally that he was, he now subordinated everything to the one essential of manoeuvring so as to remain in communication with Blücher. It was 02:00 on 18 June before he received the answer to his suggestion.[26]

Early on 17 June the Prussians drew off northwards on three roads, Thielemann covering the withdrawal and moving via Gembloux to join hands with Bülow. The French cavalry on the right, hearing troops in motion on the Namur road, dashed in pursuit down the turnpike road shortly after dawn, caught up the fugitives and captured them. They turned out to be stragglers; but their capture for a time helped to confirm the idea, prevalent in the French army, that Blücher was drawing off towards his base. Some delay too was necessary before Napoleon could finally settle on his plan for this day. The situation was still obscure, details as to what had happened on the French left were wanting, and the direction of Blücher's retreat was by no means certain. Orders, however, were sent to Ney, about 08:00, to take up his position at Quatre Bras, and if that was impossible he was to report at once and Napoleon would co-operate.[26]

Napoleon clearly meant that Ney should attack whatever happened to be in his front. If confronted by a rear-guard he would drive it off and occupy Quatre Bras; and if Wellington was still there Marshal Ney would promptly engage and hold fast the Anglo-allied army, and report to Napoleon. Napoleon would in this case hasten up with the Reserves and crush Wellington. Wellington in fact was there; but Ney did nothing whatever to retain him, and Wellington began his withdrawal to Mont-Saint-Jean about 10:00. The last best chance of bringing about a decisive French success was thus allowed to slip away.[26]

Meanwhile, Napoleon paid a personal visit about 10:00 to the Ligny battlefield, and about 11:00 he came to a decision. He sent the I Cavalry Corps (Pajol's light cavalry) the II Cavalry Corps (Exelmans heavy cavalry), the III Infantry Corps (Vandamme's), the IV Infantry Corps (Gerard's), and the 21st Division (Teste's) seconded from the VI Infantry Corps — a force of 33,000 men and 110 guns, to follow the Prussians, discover their intentions and discover if they intend to unite with Wellington in front of Brussels. As Exelmans' dragoons had already gained touch of the Prussian III Corps at Gembloux, Napoleon directed Marshal Grouchy, to whom he handed over the command of this force, to "proceed to Gembloux".[26] This order the marshal only too literally obeyed. After an inconceivably slow and wearisome march, in one badly arranged column moving on one road, he only reached Gembloux on 17 June, and halted there for the night. His cavalry gained contact before noon with Thielemann's corps, which was resting at Gembloux, but the enemy was allowed to slip away and contact was lost for want of a serious effort to keep it. The historian Archibald Becke, the author or the Encyclopædia Britannica's article on the Waterloo Campaign (1911), states that Grouchy did not proceed to the front, and entirely failed to appreciate the situation at this critical juncture. Pressing danger could only exist if Blücher had gone northwards, and northwards, therefore, in the Dyle valley, he should have diligently sought for traces of the Prussian retreat, but, according to Becke, there appears to be no reason to believe that Grouchy pushed any reconnaissance to the northward and westward of Gentinnes on 17 June; had he done so, touch with Blücher's retiring columns must have been established, and the direction of the Prussian retreat made clear. However Chesney writing in 1868 states that Marshal Grouchy assimilating intelligence provided him by his outpost services that three Prussian corps were believed to be concentrating near Brussels in and around Wavre and so were in a position to support Wellington, and that this information was collected and sent in a despatch to Napoleon by Grouchy at 22:00 on the night of 17 June.[28] Also the right of Milhaud's cuirassier corps, whilst marching from Marbais to Quatre Bras, saw a column of Prussian infantry retiring towards Wavre, and Milhaud reported this fact about 21:00 to Napoleon, who, however, attached little weight to it.[26]

Marshal Grouchy moved to Genappe with the right wing of the Army of the North, assimilating intelligence provided him by his outpost services. Three Prussian corps had moved through the area and were believed to be concentrating near Brussels to support Wellington.[28] This information was collected and sent by Marshal Grouchy at 22:00 on the night of 17 June. In this letter Grouchy noted the concentration of the Prussians in and around Wavre.[28] This was of concern to both Grouchy and Napoleon because the Prussians could use the road through Wavre straight to the assembled armies of Wellington.

Had Blücher gone eastwards, Grouchy, holding the Dyle, could easily have held back any future Prussian advance towards Wellington. Grouchy, however, went to Gembloux as ordered. By nightfall the situation was all in favour of the coalition; for Grouchy was now actually outside the four Prussian corps, who were by this time concentrated astride the Dyle at Wavre. Their retreat having been unmolested, the Prussians were ready once more to take the field, quite twenty-four hours before Napoleon deemed it possible for the foe defeated at Ligny.[26]

On the other flank, too, things had gone all in favour of Wellington. Although Napoleon wrote to Ney again at noon, from Ligny, that troops had now been placed in position at Marbais to second the marshal's attack on Quatre Bras, yet Ney remained quiescent, and Wellington effected so rapid and skilful a retreat that, on Napoleon's arrival at the head of his supporting corps,[26] be found only Wellington's cavalry screen and some horse artillery still in position.[29]

On learning of Ney's lethargy Napoleon angrily declared that Ney had ruined France. This was the fatal mistake of the campaign, and Fortune turned now against her former favourite. Although the smouldering fires of his old energy flamed out once more and Napoleon began a rapid pursuit of the cavalry screen, which crumpled up and decamped as he advanced, yet all his efforts were powerless to entangle the Anglo-allied rearguard in such a way as to hamper the retreat of Wellington's infantry. The pursuit, too, was carried out in the midst of a thunderstorm of monsoon intensity which broke at the roar of the opening cannonade, and very considerably retarded the French pursuit. It was not until the light was failing that Napoleon reached the heights of Rossomme opposite to Wellington's position and, by a masterly reconnaissance in force, compelled Wellington to disclose the presence of practically the whole Anglo-allied army.[29]

The French halted, somewhat loosened by pursuit, between Rossomme and Genappe and spent a wretched night in the sodden fields. During the night Wellington received the reassuring news that Blücher would bring two corps certainly, and possibly four, to Waterloo, and determined to accept battle.[29]

Napoleon's plan being to penetrate between the allies and then defeat them successively, the left was really the threatened flank of the Anglo-allied army.[29][30] Yet so far was Wellington from divining Napoleon's object that he stationed 17,000 men (including Colville's British division) at Hal and Tubize, 8 miles (13 km) away to his right, to repel the turning movement that he groundlessly anticipated and to form a rallying point for his right in case his centre was broken. By deliberately depriving himself of this detachment, on 18 June, Wellington ran a very grave risk. With the 67,600 men whom he had in hand, however, he took up a truly admirable "Wellingtonian" position astride the Nivelles-Brussels and Charleroi-Brussels roads which meet at Mont-Saint-Jean. He used a low ridge to screen his main defensive position, exposing comparatively few troops in front of the crest. Of his 156 guns, 78 belonged to the British artillery; but of his 67,600 men only 29,800 were British or King's German Legion troops, whereas all Napoleon's were Frenchmen and veterans.[29]

Wellington occupied Hougoumont in strength, chiefly with detachments of the British Guards; and he also placed a garrison of the British King's German Legion (K.G.L.) in La Haye Sainte, the tactical key of the Anglo-allied position. Both these farms were strengthened; but, still nervous about his right flank, Wellington occupied Hougoumont in much greater force than La Haye Sainte, and massed the bulk of his troops on his right. The main position was very skilfully taken up, and care was taken to distribute the troops so that the indifferent and immature were closely supported by those who were "better disciplined and more accustomed to war".[29] Owing to a misconception, one Dutch-Belgian brigade formed up in front of the ridge. Full arrangements were made for Blücher's co-operation through General Müffling, the Prussian attaché on Wellington's staff.[29]

Wellington was to stand fast to receive the attack, whilst the Prussians should close round Napoleon's exposed right and support Wellington's left. The Prussians were thus the real general reserve, and it was Wellington's task to receive Napoleon's attack and prepare him for the decisive counter-stroke.[29]

Waterloo (18 June)

_-_Waterloo_2.jpg)

It was at Waterloo on 18 June 1815 that the decisive battle of the campaign took place. The start of the battle was delayed for several hours as Napoleon waited until the ground had dried from the previous night’s rain. By late afternoon the French army had not succeeded in driving Wellington's forces from the escarpment on which they stood. Once the Prussians arrived, attacking the French right flank in ever increasing numbers, Napoleon's key strategy of keeping the Seventh Coalition armies divided had failed and his army was driven from the field in confusion, by a combined coalition general advance.

On the morning of 18 June 1815 Napoleon sent orders to Marshal Grouchy, commander of the right wing of the Army of the North, to harass the Prussians to stop them reforming. These orders arrived at around 06:00 and his corps began to move out at 08:00; by 12:00 the cannon from the Battle of Waterloo could be heard. Grouchy's corps commanders, especially Gérard, advised that they should "march to the sound of the guns".[31] As this was contrary to Napoleon's orders ("you will be the sword against the Prussians' back driving them through Wavre and join me here") Grouchy decided not to take the advice. It became apparent that neither Napoleon nor Marshal Grouchy understood that the Prussian army was no longer either routed or disorganised.[32] Any thoughts of joining Napoleon were dashed when a second order repeating the same instructions arrived around 16:00.

Wavre (18–19 June)

Following Napoleon's orders Grouchy attacked the Prussian III Corps under the command of General Johann von Thielmann near the village of Wavre. Grouchy believed that he was engaging the rearguard of a still-retreating Prussian force. However, only one Corps remained; the other three Prussian Corps (I, II and the still fresh IV) had regrouped after their defeat at Ligny and were marching toward Waterloo.

The next morning the Battle of Wavre ended in a hollow French victory. Grouchy's wing of the Army of the North withdrew in good order and other elements of the French army were able to reassemble around it. However, the army was not strong enough to resist the combined coalition forces, so it retreated toward Paris.

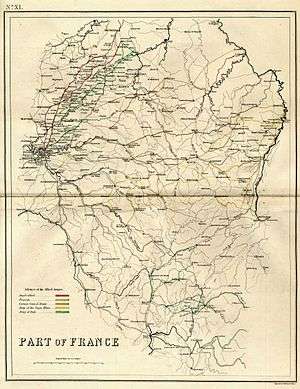

Invasion of France and the occupation of Paris (18 June – 7 July)

First week (18 June – 7 July)

After the combined victory at Waterloo by the Anglo-allies under the command of the Duke of Wellington and the Prussians under the command of Prince Blücher, it was agreed by the two commanders, on the field of Waterloo, that the Prussian army, not having been so much crippled and exhausted by the battle, should undertake the further pursuit, and proceed by Charleroi towards Avesnes and Laon; whilst the Anglo-allied army, after remaining during the night on the field, should advance by Nivelles and Binche towards Péronne.[33]

The 4,000 Prussian cavalry, that kept up an energetic pursuit during the night of 18 June, under the guidance of Marshal Gneisenau, helped to render the victory at Waterloo still more complete and decisive; and effectually deprived the French of every opportunity of recovering on the Belgian side of the frontier and to abandon most of their cannons.[34][35]

A defeated army usually covers its retreat by a rear guard, but here there was nothing of the kind. The rearmost of the fugitives having reached the river Sambre, at Charleroi, Marchienne-au-Pont, and Châtelet, by daybreak of 19 June 1815, indulged themselves with the hope that they might then enjoy a short rest from the fatigues which the relentless pursuit by the Prussians had entailed upon them during the night; but their fancied security was quickly disturbed by the appearance of a few Prussian cavalry, judiciously thrown forward towards the Sambre from the Advanced Guard at Gosselies. They resumed their flight, taking the direction of Beaumont and Philippeville.[36]

From Charleroi, Napoleon proceeded to Philippeville; whence he hoped to be able to communicate more readily with Marshal Grouchy (who was commanding the detached and still intact right wing of the Army of the North). He tarried for four hours expediting orders to generals Rapp, Lecourbe, and Lamarque, to advance with their respective corps by forced marches to Paris (for their corps locations see the military mobilisation during the Hundred Days): and also to the commandants of fortresses, to defend themselves to the last extremity. He desired Marshal Soult to collect together all the troops that might arrive at this point, and conduct them to Laon; for which place he himself started with post horses, at 14:00.[37]

The French army, under Soult, retreated on Laon in great confusion. The troops commanded by Grouchy, which had reached Dinant, retired in better order; but they were cut off from the wreck of the main army, and also from the direct road to Paris. Grouchy, therefore, was compelled to take the road to Rethel whence he proceeded to Rheims; and by forced marches he endeavoured to force a junction with Soult, and thus reach the capital before the Coalition armies.[38]

In the meantime, Wellington proceeded rapidly into the heart of France; but as there was no enemy in the field to oppose his progress, the fortresses alone demanded his attention. On 20 June 1815 an order of the day was issued to the British army before they entered France. It placed the officers and men in his army under military order to treat the ordinary French population as if they were members of an Coalition nation.[39] This by and large Wellington's army did paying for food and lodgings. This was in sharp contrast to the Prussian army, whose soldiers treated the French as enemies, plundering the populace and wantonly destroying property during their advance.[40]

From Beaumont,[lower-alpha 2] the Prussians advanced to Avesnes, which surrendered to them on 21 June. The French at first seemed determined to defend the place to the last extremity, and made considerable resistance; but a magazine having blown up, by which 400 men were killed, the rest of the garrison, which consisted chiefly of national-guards, and amounting to 439 men, surrendered at discretion.[40] On capture of the town the Prussian soldiers, treated it as a captured enemy town (rather that on liberated for their ally King Louis XVIII), and on entering the town, the greatest excesses were committed by the Prussian soldiery, which instead of being restrained was encouraged by their officers.[40]

On his arrival at Malplaquet—the scene of one of the Duke of Marlborough's victories—Wellington, issued the Malplaquet proclamation to the French people on the night 21/22 June 1815, in which be referred to the order of the day addressed to his army, as containing an explanation of the principles by which his army would be guided.[40]

Napoleon arrived in Paris, three days after Waterloo (21 June), still clinging to the hope of concerted national resistance; but the temper of the chambers and of the public generally forbade any such attempt. Napoleon and his brother Lucien Bonaparte were almost alone in believing that, by dissolving the chambers and declaring Napoleon dictator, they could save France from the armies of the powers now converging on Paris. Even Davout, minister of war, advised Napoleon that the destinies of France rested solely with the chambers. Clearly, it was time to safeguard what remained; and that could best be done under Talleyrand's shield of legitimacy.

Napoleon himself at last recognised the truth. When Lucien pressed him to "dare", he replied, "Alas, I have dared only too much already".[41] On 22 June 1815 he abdicated in favour of his son, Napoléon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte, well knowing that it was a formality, as his four-year-old son was in Austria.[41]

With the abdication of Napoleon (22 June) the French Provisional Government led by Fouché appointed Marshal Davout, Napoleon’s minister of war, as General in Chief of the army, and opened peace negotiations with the two Coalition commanders.[42]

On 24 June, Sir Charles Colville took the town of Cambrai by escalade, the governor retiring into the citadel, which he afterwards surrendered on 26 June, when it was given up to the order of Louis XVIII. Saint-Quentin was abandoned by the French, and was occupied by Blücher: and, on the evening of 24 June, the castle of Guise surrendered to the Prussian army. The Coalition armies, at least 140,000 strong, continued to advance.[43]

Second week (25 June – 1 July)

On 25 June Napoleon received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed Provisional Government (and Napoleon's former police chief), an intimation that he must leave Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the former home of Joséphine, where she had died shortly after his first abdication.[41]

On 27 June, Le Quesnoy surrendered to Wellington's army. The garrison, which amounted to 2,800 men, chiefly national-guards, obtained liberty to retire to their homes.[43]

On 26 June, Péronne was taken by the British troops. The first brigade of guards, under Major-general Maitland, took by storm the horn-work which covers the suburbs on the left of the Somme, and the place immediately surrendered, upon the garrison obtaining leave to retire to their homes.[43]

On 28 June, the Prussians, under Blücher, were at Crépy, Senlis, and La Ferté-Milon; and, on 29 June, their advanced guards were at Saint-Denis and Gonesse. The resistance experienced by the British army at Cambrai and Péronne, detained them one day behind the Prussian army; but forced marches enabled them to overtake it in the neighbourhood of Paris.[43]

In the meantime, Soult was displaced from the chief command of the army, which was conferred on Marshal Grouchy. The reason of this remarkable step, according to Soult, was because the Provisional Government suspected his fidelity. This was very likely the true reason; or they could scarcely at this moment have dismissed a man clearly superior to his successor, in point of abilities.[43]

The rapid advance of the Coalition armies caused Grouchy to redouble his speed to reach Paris before them. This he effected, after considerable loss, particularly on the 28th, at the Battle of Villers-Cotterêts where he fell in with the left wing of the Prussian army, and afterwards with the division under General Bülow, which drove him across the river Marne, with the loss of six pieces of cannon and 1,500 prisoners. Grouchy fairly acknowledged, that his troops would not fight, and that numbers deserted. In fact, though the French army was daily receiving reinforcements from the towns and depots in its route, and also from the interior, the desertion from it was so great that its number was little if any thing at all augmented.[43]

With the remainder, however, Grouchy succeeded in retreating to Paris, where he joined the wreck of the main army, the whole consisting of about 40 or 50,000 troops of the line, the wretched remains (including also all reinforcements) of 150,000 men, which fought at Quatre Bras and Waterloo. To these, however, were to be added the national-guards, a new levy called les Tirailleurs de la Garde, and the Federés. According to Bonaparte's portfolio, found at Waterloo, these latter amounted to 14,000 men. Altogether, these forces were at least 40,000 more, if not a greater number. Paris was, therefore, still formidable, and capable of much resistance.[43]

On 29 June the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States.[41] The presence of blockading Royal Navy warships under Vice Admiral Henry Hotham with orders to prevent his escape forestalled this plan.[44]

Meanwhile, Wellington continued his operations with unabating activity. As the armies approached the capital, Fouché, president of the Provisional Government, wrote a letter to the British commander, asking him to halt the progress of war.[43]

On 30 June Blücher made a movement which proved decisive of the fate of Paris. Blücher having taken the village of Aubervilliers, made a movement to his right, and crossing the Seine at Lesquielles-Saint-Germain, downstream of the capital, threw his whole force, (apart from a skeleton force holding the Coalition line north of the city) upon the west-south side of the city, where no preparations had been made to receive an enemy.[45]

On 1 July Wellington's army arrived in force and occupied the Coalition lines north of Paris. South of Paris, at the Battle of Rocquencourt a combined arms French force of commanded by General Exelmans destroyed a Prussian brigade of hussars under the command of Colonel von Sohr (who was severely wounded and taken prisoner during the skirmish),[46] but this did not prevent the Prussians moving their whole army to the south side.[45]

Third week (2–7 July)

By the morning of 2 July, Blücher had his right at Plessis-Piquet, and his left at Meudon, with his reserves at Versailles.[45] This was a thunderbolt to the French; and it was then that their weakness and the Coalition strength was seen in the most conspicuous point of view; because, at this moment, the armies of Wellington and Blücher were separated, and the all the French army, between them, yet the French could not move to prevent their junction (to shorten their lines of communications Wellington, threw a bridge over the Seine at Argenteuil, crossed that river close to Paris, and opened the communication with Blücher). After the war Lazare Carnot (Napoleon's Minister of Internal Affairs) blamed Napoleon for not fortifying Paris on the south side, and said he forewarned Napoleon of this danger.[45][45]

To defend against the Prussian move, the French were obliged to move two corps over the Seine to meet Blücher. The fighting to the south of Paris on 2 July, was obstinate, but the Prussians finally surmounted all difficulties, and succeeded in establishing themselves firmly upon the heights of Meudon and in the village of Issy. The French loss, on this day, was estimated at 3,000 men.[45]

The early next morning (3 July) at around 03:00,[45] General Dominique Vandamme (under Davout's command) was decisively defeated by General Graf von Zieten (under Blücher's command) at the Battle of Issy, forcing the French to retreat into Paris.[47][46] All further resistance, it was now obvious, would prove unavailing. Paris now lay at the mercy of the Coalition armies. The French high command decided that, providing terms were not too odious, they would capitulate and ask for an immediate armistice.[48][45]

Delegates from both sides met at Palace of St. Cloud and the result of the delegates' deliberations was the surrender of Paris under the terms of the Convention of St. Cloud.[49] As agreed in the Convention, on 4 July, the French Army, commanded by Marshal Davoust, left Paris and proceeded on its march to the southern side of Loire. On 6 July, the Anglo-allied troops occupied the Barriers of Paris, on the right of the Seine; while the Prussians occupied those upon the left bank. On 7 July, the two Coalition armies entered the centre of Paris. The Chamber of Peers, having received from the Provisional Government a notification of the course of events, terminated its sittings; the Chamber of Representatives protested, but in vain. Their President (Lanjuinais) resigned his Chair; and on the following day, the doors were closed, and the approaches guarded by Coalition troops.[50][51]

Aftermath

On 8 July, the French King, Louis XVIII, made his public entry into Paris, amidst the acclamations of the people, and again occupied the throne.[50]

On 10 July, the wind became favourable for Napoleon to set sail from France. But a British fleet made its appearance and made escape by sea impossible. Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of HMS Bellerophon early in the morning of 15 July and was transported to England.[50] Napoleon was exiled to the island of Saint Helena where he died in May 1821.

Some commandants of the French fortresses did not surrender upon the fall of the Provisional Government on 8 July 1815 and continued to hold out until forced to surrender by Commonwealth forces. The last to do so was Fort de Charlemont which capitulated on 8 September (see reduction of the French fortresses in 1815).[52]

In November 1815 a formal Peace treaty between France and the Seventh Coalition was signed. The Treaty of Paris (1815) was not as generous to France as the Treaty of Paris (1814) had been. France lost territory, had to pay reparations, and agreed to pay for an army of occupation for not less than five years.

Analysis

This campaign was the subject of a major strategic-level study by the famous Prussian political-military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, Feldzug von 1815: Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815,[53] Written c. 1827, this study was Clausewitz's last such work and is widely considered to be the best example of Clausewitz's mature theories concerning such studies.[54] It attracted the attention of Wellington's staff, who prompted him to write his only published essay on the campaign (other than his immediate, official after-action report — "Waterloo dispatch to Lord Bathurst"), his 1842 Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo.[55] This exchange with Clausewitz was quite famous in Britain in the 19th century (it was heavily discussed in, for example, Chesney's Waterloo Lectures (1868). It seems, however, to have been systematically ignored by British historians writing since 1914, probably because it drew too much attention to the decisive German role in Wellington's victory—which Wellington himself was perfectly happy to acknowledge.[56]

Timeline

See also Timeline of the Napoleonic era

| Dates | Synopsis of key events |

|---|---|

| 26 February | Napoleon slipped away from Elba. |

| 1 March | Napoleon landed near Antibes. |

| 13 March | The powers at the Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw. |

| 14 March | Marshal Ney, who had said that Napoleon ought to be brought to Paris in an iron cage, joined him with 6,000 men. |

| 15 March | After he had received word of Napoleon's escape, Joachim Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law and the King of Naples, declared war on Austria in a bid to save his crown. |

| 20 March | Napoleon entered Paris – The start of the One Hundred Days. |

| 25 March | The United Kingdom, Russia, Austria and Prussia, members of the Seventh Coalition, bound themselves to put 150,000 men each into the field to end Napoleon's rule. |

| 9 April | The high point for the Neapolitans as Murat attempted to force a crossing of the River Po. However, he is defeated at the Battle of Occhiobello and for the remainder of the war, the Neapolitans would be in full retreat. |

| 3 May | General Bianchi's Austrian I Corps decisively defeated Murat at the Battle of Tolentino. |

| 20 May | The Neapolitans signed the Treaty of Casalanza with the Austrians after Murat had fled to Corsica and his generals had sued for peace. |

| 23 May | Ferdinand IV was restored to the Neapolitan throne. |

| 15 June | French Army of the North crossed the frontier into the United Netherlands (in modern-day Belgium). |

| 16 June | Napoleon beat Field Marshal Blücher at the Battle of Ligny. Simultaneously Marshal Ney and The Duke of Wellington fought the Battle of Quatre Bras at the end of which there was no clear victor. |

| 18 June | After the close, hard-fought Battle of Waterloo, the combined armies of Wellington and Blücher decisively defeated Napoleon's French Army of the North. The concurrent Battle of Wavre continued until the next day when Marshal Grouchy won a hollow victory against General Johann von Thielmann. |

| 21 June | Napoleon arrived back in Paris. |

| 22 June | Napoleon abdicated in favour of his son Napoléon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte. |

| 29 June | Napoleon left Paris for the west of France. |

| 3 July | French requested a ceasefire following the Battle of Issy. The Convention of St. Cloud (the surrender of Paris) ended hostilities between France and the armies of Blücher and Wellington. |

| 7 July | Graf von Zieten's Prussian I Corps entered Paris along with other coalition forces. |

| 8 July | Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne – The end of the One Hundred Days. |

| 15 July | Napoleon surrendered to Captain Maitland of HMS Bellerophon. |

| 13 October | Joachim Murat is executed in Pizzo after he had landed there five days earlier hoping to regain his kingdom. |

| 16 October | Napoleon is exiled to St. Helena. |

| 20 November | Treaty of Paris signed. |

| 7 December | After being condemned by the Chamber of Peers, Marshal Ney is executed by firing squad in Paris near the Luxembourg Garden. |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Georg Dubislav Ludwig von Pirch: 'Pirch I', the use of Roman numerals being used in Prussian service to distinguish officers of the same name, in this case from his brother, seven years his junior, Otto Karl Lorenz 'Pirch II'

- ↑ now in Belgium

- ↑ Baines 1818, p. 433.

- ↑ Barbero 2006, p. 2.

- 1 2 Glover 1973, p. 178.

- ↑ Chartrand 1998, pp. 9,10.

- ↑ Houssaye 2005, p. 327.

- ↑ Houssaye 2005, p. 53.

- ↑ Chandler 1981, p. 25.

- 1 2 Houssaye 2005, pp. 54–56.

- 1 2 Chandler 1966, p. 1016.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 1093.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, p. 34.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, p. 35.

- 1 2 Beck 1911, p. 371.

- ↑ Beck 1911, pp. 372, 373.

- ↑ Beck 1911, pp. 372.

- 1 2 3 Beck 1911, pp. 373.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Hofschroer 2006, pp. 152–157.

- ↑ Longford 1971, p. 501.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, p. 66.

- ↑ Hofschroer 2006, pp. 172–180.

- ↑ Wit, p. 3.

- ↑ Beck 1911, p. 377.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, pp. 126–129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Beck 1911, p. 378.

- 1 2 Hofschroer 2006, p. 321.

- 1 2 3 Chesney 1868, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Beck 1911, p. 379.

- ↑ Chesney 1868, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Chandler 1999, p. .

- ↑ Chesney 1868, p. 157.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 628.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 597.

- ↑ Parkinson 2000, p. 241.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 627–628.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 632.

- ↑ Gifford 1817, p. 1493.

- ↑ Gifford 1817, pp. 1493–1494.

- 1 2 3 4 Gifford 1817, p. 1494.

- 1 2 3 4 Rose 1911, p. 211.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 660–758.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gifford 1817, p. 1495.

- ↑ Cordingly 2013, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gifford 1817, p. 1505.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, pp. 748–753.

- ↑ Wood 1907, Issy.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 754.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 754–756.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 757.

- ↑ Waln 1825, p. 463.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 780.

- ↑ Clausewitz 1990, pp. 936–1118.

- ↑ Moran 2010.

- ↑ Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo."

- ↑ Bassford 2010.

References

- Baines, Edward (1818), History of the Wars of the French Revolution, from the breaking out of the wars in 1792, to, the restoration of general peace in 1815 (in 2 volumes), 2, Longman, Rees, Orme and Brown, p. 433

- Barbero, Alessandro (2006), The Battle: a new history of Waterloo, Walker & Company, ISBN 0-8027-1453-6

- Chandler, David (1966), The Campaigns of Napoleon, New York: Macmillan

- Chandler, David (1981) [1980], Waterloo: The Hundred Days, Osprey Publishing

- Chandler, David (1999) [1979], Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars, Wordsworth editions, ISBN 1-84022-203-4

- Chartrand, Rene (1998), British Forces in North America 1793–1815, Osprey Publishing

- Chesney, Charles Cornwallis (1868), Waterloo Lectures: a study of the Campaign of 1815, London: Longmans Green and Co.

- Clausewitz, Carl von; Wellesley, Arthur, First Duke of Wellington (2010), Bassford, Christopher; Moran, Daniel; Pedlow, Gregory, eds., On Waterloo: Clausewitz, Wellington, and the Campaign of 1815, Clausewitz.com, ISBN 978-1-4537-0150-8 This on-line text contains Clausewitz's 58-chapter study of the Campaign of 1815 and Wellington's lengthy 1842 essay written in response to Clausewitz, as well as supporting documents and essays by the editors.

- Bassford, Christopher, "Introduction",

- Moran, Daniel, "Waterloo: Napoleon at Bay",

- Clausewitz, Carl von (1966–1990), "Feldzug von 1815: Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815", in Hahlweg, Werner, Schriften—Aufsätze—Studien—Briefe, 2 (part 2) (2 volumes in 3 ed.), Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 936–1118 — English title: "The Campaign of 1815: Strategic Overview of the Campaign".

- Cordingly, David (2013), Billy Ruffian, A&C Black, p. 7, ISBN 978-1-4088-4674-2

- Glover, Michael (1973), Wellington as Military Commander, London: Sphere Books

- Hofschroer, Peter (2006), 1815 The Waterloo Campaign: Wellington, his German allies and the Battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras, 1, Greenhill Books

- Houssaye, Henri (2005), Napoleon and the Campaign of 1815: Waterloo, Naval & Military Press Ltd

- Longford, Elizabeth (1971), Wellington: the Years of the Sword, Panther

- Parkinson, Roger (2000), Hussar General: The Life of Blucher, Man of Waterloo (illustrated ed.), Wordsworth Editions, p. 241, ISBN 9781840222531

Rose, John Holland (1911), "Napoleon I.", in Chisholm, Hugh, Encyclopædia Britannica, 19 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 190–211

Rose, John Holland (1911), "Napoleon I.", in Chisholm, Hugh, Encyclopædia Britannica, 19 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 190–211- Waln, Robert (1825), Life of the Marquis de La Fayette: Major General in the Service of the United States of America, in the War of the Revolution..., J. P. Ayres, p. 463

- Wit, Pierre de, "Part 5: The last Anglo-Dutch-German reinforcements and the Anglo-Dutch-German advance" (PDF), The campaign of 1815: a study, p. 3, retrieved June 2012 Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) -

Wood, James, ed. (1907), "Issy", The Nuttall Encyclopædia, London and New York: Frederick Warne

Wood, James, ed. (1907), "Issy", The Nuttall Encyclopædia, London and New York: Frederick Warne - Bernard Cornwell (2014), Waterloo

- Attribution

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Beck, Archibald Frank (1911), "Waterloo Campaign", in Chisholm, Hugh, Encyclopædia Britannica, 28 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 371–381

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Beck, Archibald Frank (1911), "Waterloo Campaign", in Chisholm, Hugh, Encyclopædia Britannica, 28 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 371–381  This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Gifford, C. H. (1817), History of the Wars Occasioned by the French Revolution, from the Commencement of Hostilities in 1792, to the End of 1816: Embracing a Complete History of the Revolution, W. Lewis, p. 1493–1495

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Gifford, C. H. (1817), History of the Wars Occasioned by the French Revolution, from the Commencement of Hostilities in 1792, to the End of 1816: Embracing a Complete History of the Revolution, W. Lewis, p. 1493–1495-

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Siborne, William (1848), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable

This article incorporates text from a work in the public domain: Siborne, William (1848), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waterloo Campaign. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Waterloo Campaign |

- Haweis, James Walter (1908), The campaign of 1815, chiefly in Flanders, Edinburgh and London, W. Blackwood and sons

- Booth, John (1815), The Battle of Waterloo: Containing the Accounts Published by Authority, British and Foreign, and Other Relative Documents, with Circumstantial Details, Previous and After the Battle, from a Variety of Authentic and Original Sources: to which is Added an Alphabetical List of the Officers Killed and Wounded, from 15th to 26th June, 1815, and the Total Loss of Each Regiment, London

- Hyde, Kelly, William (1905), The battle of Wavre and Grouchy's retreat: a study of an obscure part of the Waterloo campaign, London: J. Murray battle of Wavre

- Hooper, George (1862), Waterloo, the downfall of the first Napoleon: A History of the Campaign of 1815 (with maps and plans ed.), London: Smith, Elder and Company

Maps:

- Siborne, William (1844), Atlas to William Siborne's History of the Waterloo Campaign

- Siborne, William (1895), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable p. 626 — copy

- Kabinetskaart der Oostenrijkse Nederlanden et het Prinsbisdom Luik, Kaart van Farraris, 1777

- Scenic Tours sprl (February 2013), Large scale clickable map of the start of the campaign