Tuktoyaktuk

| Tuktoyaktuk Tuktuyaaqtuuq formerly Port Brabant | |

|---|---|

| Hamlet | |

|

DEW line radar station at Tuktoyaktuk | |

| Nickname(s): Tuk | |

Tuktoyaktuk | |

| Coordinates: 69°26′34″N 133°01′52″W / 69.44278°N 133.03111°WCoordinates: 69°26′34″N 133°01′52″W / 69.44278°N 133.03111°W | |

| Country | Canada |

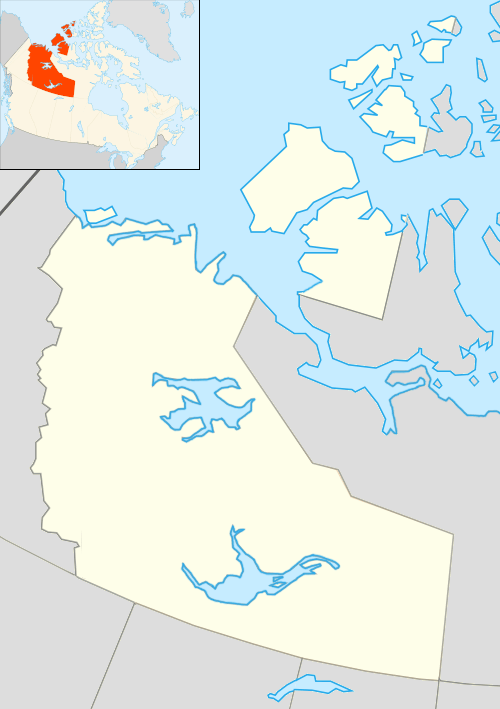

| Territory |

|

| Region | Inuvik Region |

| Electoral district | Nunakput |

| Census division | Region 1 |

| Settled | 1928 |

| Incorporated | 1 April 1970 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Darrel Nasogaluak |

| • Senior Administrative Officer | Terry Testart |

| • MLA | Jackie Jacobson |

| • Member of Parliament | Dennis Bevington |

| • Senator | Nick Sibbeston |

| Area[1] | |

| • Land | 13.90 km2 (5.37 sq mi) |

| Elevation[2] | 5 m (15 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 854 |

| • Density | 61.4/km2 (159/sq mi) |

| Time zone | MST (UTC-7) |

| • Summer (DST) | MDT (UTC-6) |

| Canadian Postal code | X0E 1C0 |

| Area code(s) | 867 |

| Telephone exchange | 977 |

| - Living cost | 172.5A |

| - Food price index | 161.6B |

| Website | www.tuk.ca/ |

|

Sources: Department of Municipal and Community Affairs,[3] Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre,[4] Canada Flight Supplement[2] Northwestel[5] Natural Resources Canada[6] ^A 2009 figure based on Edmonton = 100[7] ^B 2010 figure based on Yellowknife = 100[7] | |

Tuktoyaktuk English /tʌktəˈjæktʌk/, or Tuktuyaaqtuuq (Inuvialuktun: it looks like a caribou),[4] is an Inuvialuit hamlet of about 850 people located in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. Commonly referred to simply by its first syllable, Tuk /tʌk/, the settlement lies north of the Arctic Circle on the shore of the Beaufort Sea, of the Arctic Ocean. Formerly known as Port Brabant, the community was renamed in 1950 and was the first place in Canada to revert to the traditional Native name.[8]

History

Tuktoyaktuk is the anglicized form of the native Inuvialuit place-name, meaning "resembling a caribou". According to legend, a woman looked on as some caribou, common at the site, waded into the water and turned into stone, or became petrified. Today, reefs resembling these petrified caribou are said to be visible at low tide along the shore of the town.[9]

No formal archaeological sites exist today, but the settlement has been used by the native Inuvialuit for centuries as a place to harvest caribou and beluga whales. In addition, Tuktoyaktuk's natural harbour was historically used as a means to transport supplies to other Inuvialuit settlements.

Between 1890 and 1910, a sizeable number of Tuktoyaktuk's native families were wiped out in flu epidemics brought in by American whalers. In subsequent years, the Alaskan Dene people, as well as residents of Herschel Island, settled here. By 1937, a Hudson's Bay Company trading post was established.

Radar domes were installed beginning in the 1950s as part of the Distant Early Warning Line, to monitor air traffic and detect possible Soviet intrusions during the Cold War. The settlement's location (and harbour) made "Tuk" important in resupplying the civilian contractors and Air Force personnel along the "DEW Line." In 1947, Tuktoyaktuk became the site of one of the first government "day schools" designed to integrate Inuit youth into mainstream Canadian culture.[10]

The community of Tuktoyaktuk eventually became a base for the oil and natural gas exploration of the Beaufort Sea. Large industrial buildings remain from the busy period following the 1973 OPEC oil embargo and 1979 summertime fuel shortage. This brought many more outsiders into the region.

On 3 September 1995, the Molson Brewing Company arranged for several popular rock bands to give a concert in Tuktoyaktuk as a publicity stunt promoting their new ice-brewed beer. During the months leading up to concert, radio stations across North America ran contests in which they gave away free tickets. Dubbed The Molson Ice Polar Beach Party, it featured Hole, Metallica, Moist, Cake and Veruca Salt. Canadian film-maker Albert Nerenberg made a documentary about this concert entitled Invasion of the Beer People.[11]

In 2008, Tuktoyaktuk was featured in the second season of the reality television series Ice Road Truckers where they travelled down the Tuktoyaktuk Winter Road. It was also referenced several times in the 1994 television series Due South as a place where the main character, Benton Fraser, spent part of his childhood.[12]

In 2009, an episode of Jesse James is a Dead Man titled "Arctic Bike Journey" featured James riding a custom motorcycle across 200 kilometres (125 mi) of ice road to deliver medicine to the locals of Tuktoyaktuk.

In late 2010, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency announced that an environmental study would be undertaken on a proposed all-weather road to extend the Dempster Highway between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk.[13] Work on the highway officially started on January 8, 2014, and initial laying of the road was completed in April 2016.[14] The road is scheduled to open in fall 2017.[15]

Tuktoyaktuk has a K-12 school called Mangilaluk School as part of the Beaufort-Delta Education Council.[16] It also hosts a Community Learning Centres of Aurora College.[17]

Geography

Tuktoyaktuk is set on Kugmallit Bay, near the Mackenzie River Delta, and is located on the Arctic tree line.

Many locals still hunt, fish, and trap. Locals rely on caribou in the autumn, ducks and geese in both spring and autumn, and fishing year-round. Other activities include collecting driftwood, reindeer herding, and berrypicking. Most wages today, however, come from tourism and transportation. Northern Transportation Company Limited (NTCL) is a major employer in this region. In addition, the oil and gas industry continues to employ explorers and other workers.

Tuktoyaktuk is the gateway for exploring Pingo National Landmark, an area protecting eight nearby pingos in a region which contains approximately 1,350 of these Arctic ice-dome hills. The landmark comprises an area roughly 16 km2 (6.2 sq mi), just a few kilometres west of the community, and includes Canada's highest (the world's second-highest) pingo, at 49 m (161 ft).[18]

Demographics

At the 2011 census, the Hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk had a population of 854, down 1.8% from the 2006 census total of 870. There are 267 private dwellings, and a population density of 61.4 inhabitants per square kilometre (159/sq mi).[1] The average annual personal income in 2010 was $33,595 Canadian and the average family income was $72,913 with 30.4% below $30,000.[7] Tuktoyaktuk has a large Protestant following, with a sizeable Catholic population as well. Local languages are Inuvialuktun and English.[19] Tuktoyaktuk is predominately Inuit/Inuvialuit (79.7%) with 16.4% non-Aboriginal, 2.8% North American Indian and 1.1% Métis.[20] In 2012 the Government of the Northwest Territories reported that the population was 954 with an average yearly growth rate of -0.8 from 2001.[7]

| Historical population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: NWT Bureau of Statistics (2001-2012)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Climate

Tuktoyaktuk displays a long-winter and cold type of a subarctic climate (due to a yearly mean below −10 °C (14 °F)[21]), just short of a polar climate (tundra), as the June, July and August mean temperatures are above 10 °C (50 °F).

| Climate data for Tuktoyaktuk/James Gruben Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 3.8 | 0.7 | −0.5 | 6.4 | 23.3 | 29.6 | 34.1 | 32.9 | 21.6 | 16.4 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 34.1 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

21.1 (70) |

17.9 (64.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −23.0 (−9.4) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

−21.1 (−6) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−1.1 (30) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−20.1 (−4.2) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −26.6 (−15.9) |

−26.4 (−15.5) |

−25.1 (−13.2) |

−15.7 (3.7) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

8.9 (48) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −30.4 (−22.7) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−29.2 (−20.6) |

−20.1 (−4.2) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

−13.8 (7.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −48.9 (−56) |

−46.6 (−51.9) |

−45.5 (−49.9) |

−42.8 (−45) |

−28.9 (−20) |

−8.9 (16) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−12.8 (9) |

−36.2 (−33.2) |

−40.1 (−40.2) |

−46.7 (−52.1) |

−48.9 (−56) |

| Record low wind chill | −70.8 | −61.2 | −58.1 | −55.5 | −40.1 | −16.5 | −6.5 | −8.9 | −20.9 | −46.9 | −50.8 | −58.9 | −70.8 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 10.5 (0.413) |

8.9 (0.35) |

7.2 (0.283) |

8.3 (0.327) |

6.8 (0.268) |

11.0 (0.433) |

22.3 (0.878) |

25.7 (1.012) |

23.3 (0.917) |

18.4 (0.724) |

9.6 (0.378) |

8.7 (0.343) |

160.7 (6.327) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

1.4 (0.055) |

9.7 (0.382) |

22.2 (0.874) |

24.4 (0.961) |

15.5 (0.61) |

1.3 (0.051) |

0.0 (0) |

0.3 (0.012) |

74.9 (2.949) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 13.4 (5.28) |

10.2 (4.02) |

9.0 (3.54) |

9.4 (3.7) |

6.2 (2.44) |

1.3 (0.51) |

0.1 (0.04) |

1.2 (0.47) |

8.9 (3.5) |

20.1 (7.91) |

12.1 (4.76) |

11.2 (4.41) |

103.1 (40.59) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.4 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 10.1 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 105.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 4.3 | 10.0 | 12.4 | 9.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 38.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 8.6 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 13.0 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 72.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.2 | 73.0 | 73.9 | 81.5 | 81.5 | 68.4 | 68.7 | 73.9 | 77.9 | 85.7 | 79.5 | 76.1 | 76.2 |

| Source: Environment Canada Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010[21] Extreme temperature from 1994-2010 [22] | |||||||||||||

See also

- List of municipalities in the Northwest Territories

- Tuktoyaktuk Airport

- Tuktoyaktuk Winter Road

- Territorial claims in the Arctic

References

- 1 2 3 Tuktoyaktuk, HAM Northwest Territories (Census subdivision)

- 1 2 Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 15 September 2016 to 0901Z 10 November 2016

- ↑ "NWT Communities - Tuktoyaktuk". Government of the Northwest Territories: Department of Municipal and Community Affairs. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- 1 2 "Northwest Territories Official Community Names and Pronunciation Guide". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Yellowknife: Education, Culture and Employment, Government of the Northwest Territories. Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ Northwestel 2008 phone directory

- ↑ Canadian Geographical Names Database - Native names for Native places

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tuktoyaktuk - Statistical Profile at the GNWT

- ↑ "Infofile Detail - Native Names for Native Places". Edmonton Public Library. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Tourist guide". Tuk.ca. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- ↑ Keith J. Crowe, A History of the Original Peoples of Northern Canada, Arctic Institute of North America, McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal and London - 1974. ISBN 0-7735-0220-3

- ↑ "Website for Invasion of the Beer People". Nutaaq.com. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- ↑ "dueSouth Transcripts: The Pilot". Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ "Canadian Environmental Assessment Registry - Environmental Assessment Home Page". Ceaa.gc.ca. 2010-09-27. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- ↑ Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk Highway

- ↑ Katherine Barton (April 8, 2016). "Crews connect Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk highway in the middle". CBC News. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ Beaufort Delta Education Council

- ↑ Aurora College Community Learning Centre, Tuktoyaktuk

- ↑ Parks Canada (2005). "Pingo National Landmark". Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ "Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories, Tuktoyaktuk profile". Assembly.gov.nt.ca. Archived from the original on 2013-07-05. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- ↑ "2006 Census Tuktoyaktuk - Aboriginal profile". 2.statcan.ca. 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- 1 2 "Tuktoyaktuk climate normals 1981-2010". Environment Canada. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ "Environment Canada FTP". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tuktoyaktuk. |