Demak Sultanate

| Sultanate of Demak | ||||||||||||||

| Kasultanan Demak | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Bintara | |||||||||||||

| Languages | Javanese | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | |||||||||||||

| Government | Sultanate | |||||||||||||

| Sultan | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1475–1518 ¹ | Raden Patah | ||||||||||||

| • | 1518–1521 | Pati Unus | ||||||||||||

| • | 1521–1546 | Sultan Trenggana | ||||||||||||

| • | 1546 -1549 | Sunan Mukmin | ||||||||||||

| • | 1549 -1554 | P. Arya Penangsang | ||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||

| • | foundation of Demak port town | 1475 | ||||||||||||

| • | death of Sultan Trenggana | 1554 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ¹ (1475–1478 as vassal of Majapahit) | ||||||||||||||

The Demak Sultanate was a Javanese Muslim state located on Java's north coast in Indonesia, at the site of the present day city of Demak. A port fief to the Majapahit kingdom thought to have been founded in the last quarter of the 15th century, it was influenced by Islam brought by Muslim traders from China, Gujarat, Arabia and also from Islamic kingdoms in the region, such as Samudra Pasai and Champa. The sultanate was the first Muslim state in Java, and once dominated most of the northern coast of Java and southern Sumatra.[1]

Despite its short period, the sultanate played an important role in the establishment of Islam in Indonesia, especially on Java and neighboring area.

Origins

Demak’s origins are uncertain although it was apparently founded in the last quarter of the 15th century by a Muslim, known as Raden Patah (from Arabic name: "Fatah", also called "Pate Rodin" in Portuguese records, or "Jin Bun" in Chinese record). There is evidence that he had Chinese ancestry and perhaps was named Cek Ko-po.[2]

Raden Patah’s son, or possibly his brother, led Demak’s brief domination in Java. He was known as Trenggana, and later Javanese traditions say he gave himself the title Sultan. It appears that Trenggana had two reigns—c 1505–1518 and c 1521–1546—between which his brother in law, Yunus of Jepara occupied the throne.[2]

Before emergence of Demak, northern coast of Java was seat of many Muslim communities, both foreign merchants and Javanese. The Islamisation process gained momentum from decline of Majapahit authority. Following fall of Majapahit capital to usurper from Kediri, Raden Patah declared Demak independence from Majapahit overlordship so did nearly all northern Javanese ports.[3]

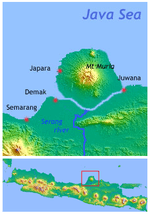

Demak was a busy harbor with trade connection to Malacca and the Spices islands. It was located at the end of a channel that separated Java and Muria Island (the channel is now filled and Muria joined with Java). From the 15th century until the 18th century, the channel was wide enough and important waterway for ships traveling along northern Javanese coast to the Spices islands. In the channel also located Serang river, which enabled access to rice producing interior of Java. This strategic location enabled Demak to rise as a leading trading center in Java.[4]

According to Tome Pires, Demak had more inhabitants than any port in Sunda or Java. Demak was the main exporter of rice to Malacca.[5] And with the rise of Malacca, so did Demak rise into prominence. Its supremacy also enhanced with claim of direct descent of Raden Patah to Majapahit royalty and his marriages ties with neighboring city-states.[4]

Rulers of Demak

Raden Patah

The foundation of Demak is traditionally attributed to Raden Patah (r. 1475–1518), a Javanese noble related to Majapahit royalty. At least one account stated that he was the son of Kertabhumi, who reigned as king Brawijaya V of Majapahit (1468–1478). Demak managed consolidate its power to defeat Daha in 1527 because it is more accepted as legitimate successor of Majapahit. The reason for this acceptance is because Raden Patah was a direct descendant of Kertabhumi who survived the Girindrawardana invasion of Trowulan in 1478.

A Chinese chronicle in a temple in Semarang states that Raden Patah founded the town of Demak in a marshy area to the north of Semarang. After the collapse of Majapahit, its various dependencies and vassals broke free, including northern Javanese port towns like Demak.[6]

The new state derived its income by trade: importing spices and exporting rice to Malacca and the Maluku Islands. It managed to gain hegemony over other Javanese trading ports on the northern coast of Java such as Semarang, Jepara, Tuban, and Gresik.[7]

The supremacy of Raden Patah was illustrated by Tome Pires," ... should de Albuquerque make peace with the Lord of Demak, all of Java will almost be forced to make peace with him... The Lord of Demak stood for all of Java".[8] Apart from Javanese city-states, Raden Patah also gained overlordship of the ports of Jambi and Palembang in eastern Sumatra, which produced commodities such as lignaloes and gold.[8] As most of its power was based on trade and control of coastal cities, Demak can be considered as a thalassocracy.

Pati Unus

Raden Patah was succeeded by his brother-in-law Pati Unus or Adipati Yunus (r. 1518–1521), king of Jepara.[2] Before ascending to Demak throne, he was a ruler of Jepara, a vassal state to the north of Demak. He was known for his two attempts in 1511 and 1521 to seize the port of Malacca from the control of Portuguese.

In Suma Oriental, Tomé Pires refer to him as "Pate Onus" or "Pate Unus", brother in-law of "Pate Rodim" (Raden Patah), the ruler of Demak. During the invasions he managed to mobilize vessels from Javanese coastal cities to Malay Peninsula. Javanese ports turned against Portuguese for a number of reason, the major of them is opposition to Portuguese insistence on monopoly of spices trade. The invasion fleet consisted around one thousand vessels, but this was repulsed by the Portuguese. The destruction of this navy proved devastating to the Javanese ports, who although somewhat recovered, unable to respond properly when next colonial power came, the Dutch.

This campaign attempt ended with failures and loss of the King's life. He was later remembered as Pangeran Sabrang Lor or the Prince who crossed (the Java Sea) to North (Malay peninsula).

Sultan Trenggana

After the death of Pati Unus, the throne was contested between his brothers; Raden Kikin and Raden Trenggana. According to tradition, Prince Prawata, the son of Prince Trenggana, stole Keris Setan Kober, a powerful magical kris from Sunan Kudus, and used it to assassinate his uncle Raden Kikin by the river, since then Raden Kikin also referred to as Sekar Seda Lepen (flower that fell by the river). Raden Trenggana rise as Sultan. The Pati Unus' brother-in-law, Trenggana (r. 1522–1548), crowned by Sunan Gunungjati (one of the Wali Songo), became the third and the greatest ruler of Demak. He conquered the Hindu-based resistance in Central Java. Trenggana oversaw the spread of Demak's influence to the east and west.[2]

Following discovery of news of Portuguese-Sunda alliance, he ordered invasion to Banten and Sunda Kelapa ports of kingdom of Sunda at 1527 (Sunda Kelapa was later renamed Jayakarta). From this territories he created sultanate of Banten as vassal-state under Hasanudin, son of Gunungjati.

Trenggana spread Demak’s influence eastward and during his second campaign, he conquered the last Javanese Hindu-Buddhist state, the remnants of Majapahit. Majapahit had been in decline since the later 15th century and was in an advanced state of collapse at the time of the Demak’s conquest.[2] It was not the real Majapahit's Rajasa dynasty which defeated by Sultan Trenggana, since it was established by Girindrawardhana on Kediri, after he defeated Kertabumi and raze Trowulan into ground. Majapahit's heirlooms were brought to Demak and adopted as Demak's royal icons. Demak was able to subdue other major ports and its reach extended into some inland areas of East Java that are not thought to have been Islamised at the time. Although evidence is limited, it is known that Demak's conquests covered much of Java: Tuban, an old Majapahit port mentioned in Chinese sources from the 11th century, was conquered c. 1527;

He appointed his daughter, Ratna Kencana (popularly known as Ratu Kalinyamat), and her husband Sultan Hadlirin, as the ruler of Kalinyamat and Jepara. He also appointed Jaka Tingkir as the duke of Pajang and gave his daughter in the hand of marriage to Jaka Tingkir. His campaign ended when he was killed in Panarukan, East Java in 1548.

Sunan Mukmin

The death of the strong and able Trenggana sparked the civil war of succession between the king's son, Sunan Mukmin[|Prince Mukmin]]; and Prince Arya Penangsang the King of Djpang Vazal of Demak the son of late Sekar Seda Lepen (Raden Kikin). Mukmin (r. 1546–1549), the son of Trenggana, ascend to throne as the fourth monarch and the new Sultan of Demak. However, Arya Penangsang of Jipang with the help of his teacher, Sunan Kudus, took revenge by sending an assassin to kill Prawata using the same kris that kill his father.

Decline

In 1549, Arya Penangsang (r. 1549–1568), the duke of Pajang ascend to the throne of Demak after assassinating his cousin Sunan Prawata. Prawata younger sister Ratu Kalinyamat seeks justice to Sunan Kudus, the teacher of Penangsang. Sunan Kudus however, decline her request since previously Prawata has committed the crime by assassinating Penangsang's father, Raden Kikin (Sekar Seda ing Lepen), thus rendered Penangsang's revenge justified. Disappointed, Ratu Kalinyamat went home with her husband, Sultan Hadlirin, from Kudus to Kalinyamat only to be attacked by Penangsang's men on their way. Hadlirin was killed in this attack while Ratu Kalinyamat barely survived. Ratu Kalinyamat seeks revenge on Penangsang, since Penangsang also murdered her husband, Sultan Hadlirin. She urged her brother in-law, Hadiwijaya (popularly known as Jaka Tingkir), Duke of Jipang (Boyolali), to kill Arya Penangsang.

Arya Penangsang soon faced heavy opposition from his vassals due to his unlikeable character, and soon was dethroned by a coalition of vassals led by Hadiwijaya, Duke of Boyolali, who had kinship with the King Trenggana. In 1568, Hadiwijaya sent his adopted son and also his son in-law Sutawijaya, who would later become the first ruler of the Mataram dynasty, to kill Penangsang.

Hadiwijaya assumed the role as the King after Penangsang is killed but he moved all the Demak heirlooms and sacred artifacts to Pajang, then he ended the Demak history when he founded his new kingdom: the short-lived Kingdom of Pajang.

Javanese legends of Demak

Later Javanese chronicles provide varying accounts of the conquest, but they all describe Demak as the legitimate direct successor of Majapahit although they do not mention the possibility that by the time of its final conquest, Majapahit no longer ruled. The first 'Sultan' of Demak, Raden Patah, is portrayed as the son of Majapahit's last king by a Chinese princess who was exiled from the court before Patah's birth.

The chronicles conventionally date the fall of Majapahit at the end of the fourteenth Javanese calendar (1400 Saka or 1478 AD), a time when changes of dynasties or court was thought to occur. Although these legends explain little about the actual events, they do illustrate that the dynastic continuity survived Islamisation of Java, or Demak's attempt to support their rule on Java by claiming the link to Majapahit dynasty as the source of political legitimation.

See also

References

- ↑ Fisher, Charles Alfred (1964). South-East Asia: A Social, Economic and Political Geography. Taylor & Francis. p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ricklefs, M.C. (2008). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C.1200. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9781137052018.

- ↑ Ooi, Keat Gin, ed. (2004). Southeast Asia: a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor (3 vols). Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576077702. OCLC 646857823.

- 1 2 Wink, André. Al-Hind: Indo-Islamic society, 14th-15th centuries. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 90-04-13561-8.

- ↑ Meilink-Roelofsz, Marie Antoinette Petronella (1962). Asian trade and European influence in the Indonesian Archipelago between 1500 and about 1630. Nijhoff.

- ↑ Muljana, Slamet (2005). Runtuhnya kerajaan Hindu-Jawa dan timbulnya negara-negara Islam di Nusantara. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: LKiS. ISBN 979-8451-16-3.

- ↑ van Naerssen, Frits Herman (1977). The economic and administrative history of early Indonesia. Leiden, Netherlands. ISBN 90-04-04918-5.

- 1 2 Pires, Tomé (1990). The Suma oriental of Tome Pires: an account of the East. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0535-7.

External links

Coordinates: 6°53′S 110°38′E / 6.883°S 110.633°E