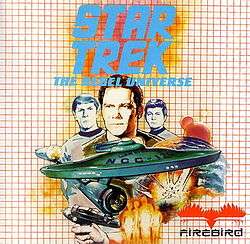

Star Trek: The Rebel Universe

| Star Trek: The Rebel Universe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Firebird Software |

| Publisher(s) | Simon & Schuster Interactive |

| Designer(s) | Mike Singleton |

| Platform(s) | Atari ST, IBM PC, Commodore 64 |

| Release date(s) | 1987 |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Star Trek: The Rebel Universe is an action-adventure computer game written by Firebird Software and published by Simon & Schuster Interactive. It was originally released for the Atari ST in 1987, and was followed the next year with versions for the Commodore 64 and IBM PC.

The game places the user in control of the bridge crew of the Enterprise while they explore an area of space attempting to understand why all previous Federation ships that entered the region have mutinied. Each member of the bridge crew is in control of certain aspects of ship operations, allowing the player to control the mission through their stations. The user can also orbit above planets and beam down selected members in order to find devices or clues that can solve the mystery of the "Quarantine Zone".

Gameplay

When the game starts the player is placed in the game's "Multivision" display that shows an oblique view of the Enterprise bridge taking up the majority of upper left portion of the screen. Running down the right side and across the bottom of this display are individual portraits of each of the bridge crew. By clicking on a person in either display, the main display is replaced by a view of the controls that crewmember operated.

For instance, clicking on Sulu replaced the main display with a new view showing Sulu and the controls he operated. From there the user could click into a 3D star map where they could select a destination star system. Backing out from that display, they could move to the warp engine controls to set their speed and start the journey. While the player operated Sulu's station, the image of Sulu on the bottom of the screen was replaced by a smaller image of the bridge, clicking there returned the user back to the main bridge display.

On the Atari version, as the user clicked through the crewmember displays their icons in the control bar would update with any useful information. For instance, if Spock was asked to scan a planet, when the user entered Sulu's screen and Spock's returned to the icon view, information about the planet would be rendered into the smaller display.

The game normally opened with the user selecting a star system to warp to. Each of the star systems was affiliated with the Federation, Klingons, Romulans or was neutral. Depending on their capabilities, friendly systems will re-fuel, repair and re-arm the Enterprise. When the Enterprise entered an enemy system there was a chance it would be defended by one or more Klingon or Romulan warships, which you could fight by moving to Chekov's station. Renegade Federation ships would also occasionally crop up as enemies. Combat took place in a 3D wireframe view, allowing the user to click on vulnerable locations on the enemy ship for maximum effect.

Star systems had between three and six planets. Once they had navigated to a system, the Enterprise could visit the individual planets using their impulse drive. Some of these were life supporting, which played a key role in the game. Once in orbit above such a planet, the player could use Kirk's screen to move to the transporter room. Here the player can select an away team, equip them with items picked up on previous missions, and beam them to the surface.

On the surface the view changed to show a 3D wireframe display of a room, either empty, containing an item that could be picked up, or with and obstacle barring further progress. The graphics were not interactive, and this portion of the game was essentially a text adventure. Each member of the crew would offer a different solution to bypassing any obstacle, and the player had to decide which solution to use. Choosing the wrong one could injure the crew or prevent further movement (hence one reason for multiple solutions, if a key element was no longer attainable). If they successfully bypassed an obstacle they would move onto the next room in series. When they reached the end of the "hallway" they often found nothing. In other cases the last room would contain a treasure of sorts, or a piece of equipment that was needed to bypass one of the obstacles on another planet. Others contained data banks that helped explain the mission and offered potential solutions to the game.

Other aspects of game play included worm holes, space-borne dangers and life forms that could prevent conflict within a star system.

The game universe was relatively large, with 4,000 planets in total, so exploration could be extremely time consuming, and the coordinate system could require something of a learning curve. And despite being on a five-year mission, the game clock would wind quickly during warp travel, drastically reducing the actual amount of time available to solve the game. Later versions of the game helped the user by providing a list of planets and the items they contained.

Reception

Compute! criticized the game's "unexpected tediousness of play". It stated that a more serious flaw was the absence of the Enterprise crew's interaction with aliens, an important part of the TV show.[1] Computer Gaming World found the graphics and audio impressive on the Atari ST but mediocre on the IBM PC. It concluded that the game was "an excellent adventure game for the ST [with] enough action and puzzles to satisfy most adventure gamers".[2] In 2014 historian Jimmy Maher described The Rebel Universe as "a sort of Lords of Midnight in space. It was full of interesting ideas, but rushed to release in an incomplete and fatally unbalanced state".[3]

References

- ↑ Randall, Neil (May 1988). "Star Trek: The Rebel Universe". Compute!. p. 61. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Battles, Hosea Jr. (October 1988). "Star Trek: The Rebel Universe". Computer Gaming World. p. 28.

- ↑ Maher, Jimmy (2014-12-17). "Simon & Schuster's Treks to Nowhere". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved 18 December 2014.