Deism

| Part of a series on |

| God |

|---|

|

In particular religions |

|

Deism (/ˈdiː.ɪzəm/ [1][2] or /ˈdeɪ.ɪzəm/), derived from a Latin word "deus" meaning "god", is a theological/philosophical position that combines the rejection of revelation and authority as a source of religious knowledge with the conclusion that reason and observation of the natural world are sufficient to determine the existence of a single creator of the universe.[3][4][5][6][7]

Deism gained prominence among intellectuals during the Age of Enlightenment—especially in Britain, France, Germany and the United States—who, raised as Christians, believed in one God but became disenchanted with organized religion and notions such as the Trinity, Biblical inerrancy and the supernatural interpretation of events such as miracles.[8] Included in those influenced by its ideas were leaders of the American and French Revolutions.[9]

Today, deism is considered to exist in two principal forms: classical and modern[10] where the classical view takes what is called a "cold" approach by asserting the non-intervention of deity in the natural behavior of the created universe, while the modern deist formulation can be either "warm" (citing an involved deity) or cold, non-interventionist creator. These lead to many subdivisions of modern deism —which tends, therefore, to serve as an overall category of belief.[11] Despite this classification of Deism today, classical Deists themselves rarely wrote or accepted that the Creator is a non-interventionist during the flowering of Deism in the 16th and 17th centuries; using straw man arguments, their theological critics attempted to force them into this position.[12][13]

Overview

Deism is a theological theory concerning the relationship between the Creator and the natural world. Deistic viewpoints emerged during the scientific revolution of 17th Century Europe and came to exert a powerful influence during the 18th Century Enlightenment. Deism stood between the narrow dogmatism of the period and skepticism. Though deists rejected atheism,[14] they often were called "atheists" by more traditional theists.[15] There were a number of different forms in the 17th and 18th Centuries. In England, deism included a range of people from anti-Christian to non-Christian theists.[16]

For Deists, human beings can know God only via reason and the observation of nature, but not by revelation or supernatural manifestations (such as miracles) —phenomena that Deists regard with caution if not skepticism. See the section Features of deism, following. Deism is related to naturalism because it credits the formation of life and the universe to a higher power, using only natural processes. Deism may also include a spiritual element, involving experiences of God and nature.[17]

The words deism and theism are both derived from words for god: the former from Latin deus, the latter from Greek theós (θεός).

Prior to the 17th Century the terms ["deism" and "deist"] were used interchangeably with the terms "theism" and "theist", respectively. ... Theologians and philosophers of the 17th Century began to give a different signification to the words... Both [theists and deists] asserted belief in one supreme God, the Creator... . But the theist taught that God remained actively interested in and operative in the world which he had made, whereas the Deist maintained that God endowed the world at creation with self-sustaining and self-acting powers and then surrendered it wholly to the operation of these powers acting as second causes.[18]

Perhaps the first use of the term deist is in Pierre Viret's Instruction Chrétienne en la doctrine de la foi et de l'Évangile (Christian teaching on the doctrine of faith and the Gospel, 1564), reprinted in Bayle's Dictionnaire entry Viret. Viret, a Calvinist, regarded deism as a new form of Italian heresy.[19] Viret wrote (as translated from the original French):

There are many who confess that while they believe like the Turks and the Jews that there is some sort of God and some sort of deity, yet with regard to Jesus Christ and to all that to which the doctrine of the Evangelists and the Apostles testify, they take all that to be fables and dreams... I have heard that there are of this band those who call themselves Deists, an entirely new word, which they want to oppose to Atheist. For in that atheist signifies a person who is without God, they want to make it understood that they are not at all without God, since they certainly believe there is some sort of God, whom they even recognize as creator of heaven and earth, as do the Turks; but as for Jesus Christ, they only know that he is and hold nothing concerning him nor his doctrine.[19]

In England, the term deist first appeared in Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621).[9]

Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583–1648) is generally considered the "father of English Deism", and his book De Veritate (1624) the first major statement of deism. Deism flourished in England between 1690 and 1740, at which time Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), also called "The Deist's Bible", gained much attention. Later deism spread to France, notably through the work of Voltaire, to Germany, and to the United States.

Features of deism

The concept of deism covers a wide variety of positions on a wide variety of religious issues. Sir Leslie Stephen's English Thought in the Eighteenth Century describes the core of deism as consisting of "critical" and "constructional" elements.

Critical elements of deist thought included:

- Rejection of religions that are based on books that claim to contain the revealed word of God.

- Rejection of religious dogma and demagogy.

- Skepticism of reports of miracles, prophecies and religious "mysteries".

Constructional elements of deist thought included:

- God exists and created the universe.

- God gave humans the ability to reason.

Individual deists varied in the set of critical and constructive elements for which they argued. Some deists rejected miracles and prophecies but still considered themselves Christians because they believed in what they felt to be the pure, original form of Christianity – that is, Christianity as it supposedly existed before it was corrupted by additions of such superstitions as miracles, prophecies, and the doctrine of the Trinity. Some deists rejected the claim of Jesus' divinity but continued to hold him in high regard as a moral teacher, a position known as Christian deism, exemplified by Thomas Jefferson's famous Jefferson Bible and Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation. Other, more radical deists rejected Christianity altogether and expressed hostility toward Christianity, which they regarded as pure superstition. In return, Christian writers often charged radical deists with atheism.

Note that the terms constructive and critical are used to refer to aspects of deistic thought, not sects or subtypes of deism – it would be incorrect to classify any particular deist author as "a constructive deist" or "a critical deist". As Peter Gay notes:

All Deists were in fact both critical and constructive Deists. All sought to destroy in order to build, and reasoned either from the absurdity of Christianity to the need for a new philosophy or from their desire for a new philosophy to the absurdity of Christianity. Each Deist, to be sure, had his special competence. While one specialized in abusing priests, another specialized in rhapsodies to nature, and a third specialized in the skeptical reading of sacred documents. Yet whatever strength the movement had—and it was at times formidable—it derived that strength from a peculiar combination of critical and constructive elements.— Peter Gay, Deism: An Anthology, p. 13

It should be noted, however, that the constructive element of deism was not unique to deism. It was the same as the natural theology that was so prevalent in all English theology in the 17th and 18th centuries. What set deists apart from their more orthodox contemporaries were their critical concerns.

Defining the essence of English deism is a formidable task. Like priestcraft, atheism, and freethinking, deism was one of the dirty words of the age. Deists were stigmatized —often as atheists— by their Christian opponents. Yet some Deists claimed to be Christian, and as Leslie Stephen argued in retrospect, the Deists shared so many fundamental rational suppositions with their orthodox opponents... that it is practically impossible to distinguish between them. But the term deism is nevertheless a meaningful one.... Too many men of letters of the time agree about the essential nature of English deism for modern scholars to ignore the simple fact that what sets the Deists apart from even their most latitudinarian Christian contemporaries is their desire to lay aside scriptural revelation as rationally incomprehensible, and thus useless, or even detrimental, to human society and to religion. While there may possibly be exceptions, ... most Deists, especially as the eighteenth century wears on, agree that revealed Scripture is nothing but a joke or "well-invented flam." About mid-century, John Leland, in his historical and analytical account of the movement [View of the Principal Deistical Writers], squarely states that the rejection of revealed Scripture is the characteristic element of deism, a view further codified by such authorities as Ephraim Chambers and Samuel Johnson. ... "DEISM," writes Stephens bluntly, "is a denial of all reveal'd Religion."— James E. Force, Introduction (1990) to An Account of the Growth of Deism in England (1696) by William Stephens

One of the remarkable features of deism is that the critical elements did not overpower the constructive elements. As E. Graham Waring observed,[20] "A strange feature of the [Deist] controversy is the apparent acceptance of all parties of the conviction of the existence of God." And Basil Willey observed:[21]

M. Paul Hazard has recently described the Deists of this time 'as rationalists with nostalgia for religion': men, that is, who had allowed the spirit of the age to separate them from orthodoxy, but who liked to believe that the slope they had started upon was not slippery enough to lead them to atheism.

Concepts of "reason"

According to the deists, our reason gives us all the information we need:

By natural religion, I understand the belief of the existence of a God, and the sense and practice of those duties which result from the knowledge we, by our reason, have of him and his perfections; and of ourselves, and our own imperfections, and of the relationship we stand in to him, and to our fellow-creatures; so that the religion of nature takes in everything that is founded on the reason and nature of things.— Matthew Tindal, Christianity as Old as the Creation (II)[22]

Consequently, the deists attempted to use reason as a critical tool for exposing and rejecting what they saw as nonsense:

I hope to make it appear that the use of reason is not so dangerous in religion as it is commonly represented ... There is nothing that men make a greater noise about than the "mysteries of the Christian religion". The divines gravely tell us "we must adore what we cannot comprehend" ... [Some] contend [that] some mysteries may be, or at least seem to be, contrary to reason, and yet received by faith. [Others contend] that no mystery is contrary to reason, but that all are "above" it. On the contrary, we hold that reason is the only foundation of all certitude ... Wherefore, we likewise maintain, according to the title of this discourse, that there is nothing in the Gospel contrary to reason, nor above it; and that no Christian doctrine can be properly called a mystery.— John Toland, Christianity Not Mysterious: or, a Treatise Shewing That There Is Nothing in the Gospel Contrary to Reason, Nor above It (1696)[23]

Arguments for the existence of God

Some deists used the cosmological argument for the existence of God - as did Thomas Hobbes in several of his writings:

The effects we acknowledge naturally, do include a power of their producing, before they were produced; and that power presupposeth something existent that hath such power; and the thing so existing with power to produce, if it were not eternal, must needs have been produced by somewhat before it, and that again by something else before that, till we come to an eternal, that is to say, the first power of all powers and first cause of all causes; and this is it which all men conceive by the name of God, implying eternity, incomprehensibility, and omnipotence.— Thomas Hobbes, Works, vol. 4, pp. 59–60; quoted in John Orr, English Deism, p. 76

History of religion and the deist mission

Most deists (see for instance Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation and Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason) saw the religions of their day as corruptions of an original, pure religion that was simple and rational. They felt that this original pure religion had become corrupted by "priests" who had manipulated it for personal gain and for the class interests of the priesthood in general.[24]

According to this world view, over time "priests" had succeeded in encrusting the original simple, rational religion with all kinds of superstitions and "mysteries" – irrational theological doctrines. Laymen were told by the priests that only the priests really knew what was necessary for salvation and that laymen must accept the "mysteries" on faith and on the priests' authority. This kept the laity baffled by the nonsensical "mysteries", confused, and dependent on the priests for information about the requirements for salvation. The priests consequently enjoyed a position of considerable power over the laity, which they strove to maintain and increase. Deists referred to this kind of manipulation of religious doctrine as "priestcraft", a highly derogatory term. As Thomas Paine wrote:

As priestcraft was always the enemy of knowledge, because priestcraft supports itself by keeping people in delusion and ignorance, it was consistent with its policy to make the acquisition of knowledge a real sin.— The Age of Reason, Part 2, p. 129

Deists saw their mission as the stripping away of "priestcraft" and "mysteries" from religion, thereby restoring religion to its original, true condition – simple and rational. In many cases, they considered true, original Christianity to be the same as this original natural religion. As Matthew Tindal put it:

It can't be imputed to any defect in the light of nature that the pagan world ran into idolatry, but to their being entirely governed by priests, who pretended communication with their gods, and to have thence their revelations, which they imposed on the credulous as divine oracles. Whereas the business of the Christian dispensation was to destroy all those traditional revelations, and restore, free from all idolatry, the true primitive and natural religion implanted in mankind from the creation.— Matthew Tindal, Christianity as Old as the Creation (XIV)[25]

One implication of this deist creation myth was that primitive societies, or societies that existed in the distant past, should have religious beliefs that are less encrusted with superstitions and closer to those of natural theology. This position gradually became less plausible as thinkers such as David Hume began studying the natural history of religion and suggesting that the origins of religion lay not in reason but in the emotions, specifically the fear of the unknown.

Freedom and necessity

Enlightenment thinkers, under the influence of Newtonian science, tended to view the universe as a vast machine, created and set in motion by a creator being, that continues to operate according to natural law, without any divine intervention. This view naturally led to what was then usually called necessitarianism[26] (the modern term is determinism): the view that everything in the universe – including human behavior – is completely causally determined by antecedent circumstances and natural law. (See, for example, La Mettrie's L'Homme machine.) As a consequence, debates about freedom versus "necessity" were a regular feature of Enlightenment religious and philosophical discussions.

Because of their high regard for natural law and for the idea of a universe without miracles, deists were especially susceptible to the temptations of determinism. Reflecting the intellectual climate of the time, there were differences among deists about freedom and determinism. Some, such as Anthony Collins, actually were necessitarians.[27]

Beliefs about immortality of the soul

Deists hold a variety of beliefs about the soul. Some, such as Lord Herbert of Cherbury and William Wollaston,[28] held that souls exist, survive death, and in the afterlife are rewarded or punished by God for their behavior in life. Some, such as Benjamin Franklin, believed in reincarnation or resurrection. Others, such as Thomas Paine, had definitive beliefs about the immortality of the soul:

I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.— Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, Part I

I trouble not myself about the manner of future existence. I content myself with believing, even to positive conviction, that the power that gave me existence is able to continue it, in any form and manner he pleases, either with or without this body; and it appears more probable to me that I shall continue to exist hereafter than that I should have had existence, as I now have, before that existence began.— Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, Part I, Recapitulation

Still others such as Anthony Collins,[29] Bolingbroke, Thomas Chubb, and Peter Annet were materialists and either denied or doubted the immortality of the soul.[30]

Deist terminology

Deist authors – and 17th- and 18th-century theologians in general used the following terms and arguments

- Divine Providence

- Supreme Being

- Divine Watchmaker

- Grand Architect of the Universe

- Nature's God. Used in the United States Declaration of Independence

- Father of Lights. Benjamin Franklin used this terminology when proposing that meetings of the Constitutional Convention begin with prayers[31]

History of classical deism

Historical background of the emergence of deism

Deistic thinking has existed since ancient times. Among the Ancient Greeks, Heraclitus conceived of a logos, a supreme rational principle, and said the wisdom "by which all things are steered through all things" was "both willing and unwilling to be called Zeus (God)". Plato envisaged God as a Demiurge or 'craftsman'. Outside ancient Greece many other cultures have expressed views that resemble deism in some respects. However, the word "deism", as it is understood today, is generally used to refer to the movement toward natural theology or freethinking that occurred in 17th-century Europe, and specifically in Britain.

Natural theology is a facet of the revolution in world view that occurred in Europe in the 17th century. To understand the background to that revolution is also to understand the background of deism. Several cultural movements of the time contributed to the movement.[32]

Discovery of diversity

The humanist tradition of the Renaissance included a revival of interest in Europe's classical past in ancient Greece and Rome. The veneration of that classical past, particularly pre-Christian Rome, the new availability of Greek philosophical works, the successes of humanism and natural science along with the fragmentation of the Christian churches and increased understanding of other faiths, all helped erode the image of the church as the unique source of wisdom, destined to dominate the whole world.

In addition, study of classical documents led to the realization that some historical documents are less reliable than others, which led to the beginnings of biblical criticism. In particular, when scholars worked on biblical manuscripts, they began developing the principles of textual criticism and a view of the New Testament being the product of a particular historical period different from their own.

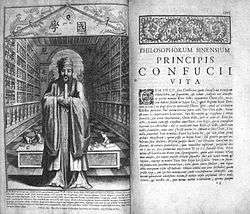

In addition to discovering diversity in the past, Europeans discovered diversity in the present. The voyages of discovery of the 16th and 17th centuries acquainted Europeans with new and different cultures in the Americas, in Asia, and in the Pacific. They discovered a greater amount of cultural diversity than they had ever imagined, and the question arose of how this vast amount of human cultural diversity could be compatible with the biblical account of Noah's descendants. In particular, the ideas of Confucius, translated into European languages by the Jesuits stationed in China, are thought to have had considerable influence on the deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Christianity.[33][34]

In particular, cultural diversity with respect to religious beliefs could no longer be ignored. As Herbert wrote in De Religione Laici (1645),

Many faiths or religions, clearly, exist or once existed in various countries and ages, and certainly there is not one of them that the lawgivers have not pronounced to be as it were divinely ordained, so that the Wayfarer finds one in Europe, another in Africa, and in Asia, still another in the very Indies.

Religious conflict in Europe

Europe had been plagued by sectarian conflicts and religious wars since the beginning of the Reformation. In 1642, when Lord Herbert of Cherbury's De Veritate was published, the Thirty Years War had been raging on continental Europe for nearly 25 years. It was an enormously destructive war that (it is estimated) destroyed 15–20% of the population of Germany. At the same time, the English Civil War pitting King against Parliament was just beginning.

Such massive violence led to a search for natural religious truths – truths that could be universally accepted, because they had been either "written in the book of Nature" or "engraved on the human mind" by God.

Advances in scientific knowledge

The 17th century saw a remarkable advance in scientific knowledge, the scientific revolution. The work of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo set aside the old notion that the earth was the center of the universe. These discoveries posed a serious challenge to biblical and religious authorities, Galileo's condemnation for heresy being an example. In consequence the Bible came to be seen as authoritative on matters of faith and morals but no longer authoritative (or meant to be) on science.

Isaac Newton's (1642–1727) mathematical explanation of universal gravitation explained the behavior both of objects here on earth and of objects in the heavens in a way that promoted a worldview in which the natural universe is controlled by laws of nature. This, in turn, suggested a theology in which God created the universe, set it in motion controlled by natural law and retired from the scene. The new awareness of the explanatory power of universal natural law also produced a growing skepticism about such religious staples as miracles (violations of natural law) and about religious books that reported them.

Precursors of deism

Early works of biblical criticism, such as Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan and Spinoza's Theologico-Political Treatise, as well as works by lesser-known authors such as Richard Simon and Isaac La Peyrère, paved the way for the development of critical deism.

An important precursor to deism was the work of Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury (d. 1648). He has been called the "father of English deism", and his book De Veritate (On Truth, as It Is Distinguished from Revelation, the Probable, the Possible, and the False) (1624) "the first major statement of deism".[35][36] However, his beliefs in divine intervention, particularly in response to prayer, are at odds with the basic ideas of deism. In Herbert's account of one incident, he prayed "I am not satisfied enough whether I shall publish this Book, De Veritate; if it be for Thy glory, I beseech Thee give me some Sign from Heaven, if not, I shall suppress it" and recounts that the response was "a loud tho' yet gentle Noise came from the Heavens (for it was like nothing on Earth)... I had the Sign I demanded".[37]

Like his contemporary Descartes, Herbert searched for the foundations of knowledge. In fact, the first two thirds of De Veritate are devoted to an exposition of Herbert's theory of knowledge. Herbert distinguished truths obtained through experience, and through reasoning about experience, from innate truths and from revealed truths. Innate truths are imprinted on our minds, and the evidence that they are so imprinted is that they are universally accepted. Herbert's term for universally accepted truths was notitiae communes – common notions.

In the realm of religion, Herbert believed that there were five common notions.[14]

- There is one Supreme God.

- He ought to be worshipped.

- Virtue and piety are the chief parts of divine worship.

- We ought to be sorry for our sins and repent of them

- Divine goodness doth dispense rewards and punishments both in this life and after it.

— Lord Herbert of Cherbury, The Antient Religion of the Gentiles, and Causes of Their Errors, pp. 3–4, quoted in John Orr, English Deism, p. 62

The following lengthy quote from Herbert can give the flavor of his writing and demonstrate the sense of the importance that Herbert attributed to innate Common Notions, which can help in understanding the effect of Locke's attack on innate ideas on Herbert's philosophy:

No general agreement exists concerning the Gods, but there is universal recognition of God. Every religion in the past has acknowledged, every religion in the future will acknowledge, some sovereign deity among the Gods. ...Accordingly that which is everywhere accepted as the supreme manifestation of deity, by whatever name it may be called, I term God.

While there is no general agreement concerning the worship of Gods, sacred beings, saints, and angels, yet the Common Notion or Universal Consent tells us that adoration ought to be reserved for the one God. Hence divine religion— and no race, however savage, has existed without some expression of it— is found established among all nations. ...

The connection of Virtue with Piety, defined in this work as the right conformation of the faculties, is and always has been held to be, the most important part of religious practice. There is no general agreement concerning rites, ceremonies, traditions...; but there is the greatest possible consensus of opinion concerning the right conformation of the faculties. ... Moral virtue... is and always has been esteemed by men in every age and place and respected in every land...

There is no general agreement concerning the various rites or mysteries which the priests have devised for the expiation of sin.... General agreement among religions, the nature of divine goodness, and above all conscience, tell us that our crimes may be washed away by true penitence, and that we can be restored to new union with God. ... I do not wish to consider here whether any other more appropriate means exists by which the divine justice may be appeased, since I have undertaken in this work only to rely on truths which are not open to dispute but are derived from the evidence of immediate perception and admitted by the whole world.

The rewards that are eternal have been variously placed in heaven, in the stars, in the Elysian fields... Punishment has been thought to lie in metempsychosis, in hell,... or in temporary or everlasting death. But all religion, law, philosophy, and ... conscience, teach openly or implicitly that punishment or reward awaits us after this life. ... [T]here is no nation, however barbarous, which has not and will not recognise the existence of punishments and rewards. That reward and punishment exist is, then, a Common Notion, though there is the greatest difference of opinion as to their nature, quality, extent, and mode.

It follows from these considerations that the dogmas which recognize a sovereign Deity, enjoin us to worship Him, command us to live a holy life, lead us to repent our sins, and warn us of future recompense or punishment, proceed from God and are inscribed within us in the form of Common Notions.

Revealed truth exists; and it would be unjust to ignore it. But its nature is quite distinct from the truth [based on Common Notions] ... [T]he truth of revelation depends upon the authority of him who reveals it. We must, then, proceed with great care in discerning what actually is revealed.... [W]e must take great care to avoid deception, for men who are depressed, superstitious, or ignorant of causes are always liable to it.

— Lord Herbert of Cherbury, De Veritate, quoted in Gay, Deism: An Anthology, pp. 29 ff.

According to Gay, Herbert had relatively few followers, and it was not until the 1680s that Herbert found a true successor in Charles Blount (1654–1693). Blount made one special contribution to the deist debate: "by utilizing his wide classical learning, Blount demonstrated how to use pagan writers, and pagan ideas, against Christianity. ... Other Deists were to follow his lead."[38]

Deism in Britain

John Locke

The publication of John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689, but dated 1690) marks a major turning point in the history of deism. Since Herbert's De Veritate, innate ideas had been the foundation of deist epistemology. Locke's famous attack on innate ideas in the first book of the Essay effectively destroyed that foundation and replaced it with a theory of knowledge based on experience. Innatist deism was replaced by empiricist deism. Locke himself was not a deist. He believed in both miracles and revelation, and he regarded miracles as the main proof of revelation.[39]

After Locke, constructive deism could no longer appeal to innate ideas for justification of its basic tenets such as the existence of God. Instead, under the influence of Locke and Newton, deists turned to natural theology and to arguments based on experience and nature: the cosmological argument and the argument from design.

Flowering of classical deism, 1690–1740

Peter Gay places the zenith of deism "from the end of the 1690s, when the vehement response to John Toland's Christianity not Mysterious (1696) started the deist debate, to the end of the 1740s when the tepid response to Conyers Middleton's Free Inquiry signalled its close."[40]

Among the Deists, only Anthony Collins (1676–1729) could claim much philosophical competence; only Conyers Middleton (1683–1750) was a really serious scholar. The best known Deists, notably John Toland (1670–1722) and Matthew Tindal (1656–1733), were talented publicists, clear without being deep, forceful but not subtle. ... Others, like Thomas Chubb (1679–1747), were self-educated freethinkers; a few, like Thomas Woolston (1669–1731), were close to madness.— Peter Gay, Deism: An Anthology[40]

During this period, prominent British deists included William Wollastson, Charles Blount, and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke.

The influential author Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury is also usually categorized as a deist. Although he did not think of himself as a deist, he shared so many attitudes with deists that Gay calls him "a Deist in fact, if not in name".[41]

Notable late-classical deists include Peter Annet (1693–1769), Thomas Chubb (1679–1747), Thomas Morgan (?–1743), and Conyers Middleton (1683–1750).

Matthew Tindal

Especially noteworthy is Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), which "became, very soon after its publication, the focal center of the deist controversy. Because almost every argument, quotation, and issue raised for decades can be found here, the work is often termed 'the deist's Bible'."[42] Following Locke's successful attack on innate ideas, Tindal's "Deist Bible" redefined the foundation of deist epistemology as knowledge based on experience or human reason. This effectively widened the gap between traditional Christians and what he called "Christian Deists", since this new foundation required that "revealed" truth be validated through human reason.

David Hume

The writings of David Hume are sometimes credited with causing or contributing to the decline of deism. English deism, however, was already in decline before Hume's works on religion (1757,1779) were published.[43]

Furthermore, some writers maintain that Hume's writings on religion were not very influential at the time that they were published.[44]

Nevertheless, modern scholars find it interesting to study the implications of his thoughts for deism.

- Hume's skepticism about miracles makes him a natural ally of deism.

- His skepticism about the validity of natural religion cuts equally against deism and deism's opponents, who were also deeply involved in natural theology. But his famous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion were not published until 1779, by which time deism had almost vanished in England.

In the Natural History of Religion (1757), Hume contends that polytheism, not monotheism, was "the first and most ancient religion of mankind". In addition, contends Hume, the psychological basis of religion is not reason, but fear of the unknown.

The primary religion of mankind arises chiefly from an anxious fear of future events; and what ideas will naturally be entertained of invisible, unknown powers, while men lie under dismal apprehensions of any kind, may easily be conceived. Every image of vengeance, severity, cruelty, and malice must occur, and must augment the ghastliness and horror which oppresses the amazed religionist. ... And no idea of perverse wickedness can be framed, which those terrified devotees do not readily, without scruple, apply to their deity.— David Hume, The Natural History of Religion, section XIII

As E. Graham Waring saw it;[20]

The clear reasonableness of natural religion disappeared before a semi-historical look at what can be known about uncivilized man— "a barbarous, necessitous animal," as Hume termed him. Natural religion, if by that term one means the actual religious beliefs and practices of uncivilized peoples, was seen to be a fabric of superstitions. Primitive man was no unspoiled philosopher, clearly seeing the truth of one God. And the history of religion was not, as the deists had implied, retrograde; the widespread phenomenon of superstition was caused less by priestly malice than by man's unreason as he confronted his experience.

Experts dispute whether Hume was a deist, an atheist, or something else. Hume himself was uncomfortable with the terms deist and atheist, and Hume scholar Paul Russell has argued that the best and safest term for Hume's views is irreligion.[45]

Deism in Continental Europe

_-001.jpg)

by Nicolas de Largillière

English deism, in the words of Peter Gay, "travelled well. ... As Deism waned in England, it waxed in France and the German states."[46]

France had its own tradition of religious skepticism and natural theology in the works of Montaigne, Bayle, and Montesquieu. The most famous of the French deists was Voltaire, who acquired a taste for Newtonian science, and reinforcement of deistic inclinations, during a two-year visit to England starting in 1726.

French deists also included Maximilien Robespierre and Rousseau. For a short period of time during the French Revolution the Cult of the Supreme Being was the state religion of France.

Kant's identification with deism is controversial. An argument in favor of Kant as deist is Alan Wood's "Kant's Deism," in P. Rossi and M. Wreen (eds.), Kant's Philosophy of Religion Re-examined (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); an argument against Kant as deist is Stephen Palmquist's "Kant's Theistic Solution".

Deism in the United States

In the United States, Enlightenment philosophy (which itself was heavily inspired by deist ideals) played a major role in creating the principle of religious freedom, expressed in Thomas Jefferson's letters and included in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. American Founding Fathers, or Framers of the Constitution, who were especially noted for being influenced by such philosophy include Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Cornelius Harnett, Gouverneur Morris, and Hugh Williamson. Their political speeches show distinct deistic influence.

Other notable Founding Fathers may have been more directly deist. These include James Madison, possibly Alexander Hamilton, Ethan Allen,[47] and Thomas Paine (who published The Age of Reason, a treatise that helped to popularize deism throughout the United States and Europe).

Unlike the many deist tracts aimed at an educated elite, Paine's treatise explicitly appealed to ordinary people, using direct language familiar to the laboring classes. How widespread deism was among ordinary people in the United States is a matter of continued debate.[48]

A major contributor was Elihu Palmer (1764–1806), who wrote the "Bible" of American deism in his Principles of Nature (1801) and attempted to organize deism by forming the "Deistical Society of New York" and other deistic societies from Maine to Georgia.[49]

In the United States there is controversy over whether the Founding Fathers were Christians, deists, or something in between.[50][51] Particularly heated is the debate over the beliefs of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington.[52][53][54]

Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography, "Some books against Deism fell into my hands; they were said to be the substance of sermons preached at Boyle's lectures. It happened that they wrought an effect on me quite contrary to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in short, I soon became a thorough Deist. My arguments perverted some others, particularly Collins and Ralph; but each of them having afterwards wrong'd me greatly without the least compunction, and recollecting Keith's conduct towards me (who was another freethinker) and my own towards Vernon and Miss Read, which at times gave me great trouble, I began to suspect that this doctrine, tho' it might be true, was not very useful."[55][56] Franklin also wrote that "the Deity sometimes interferes by his particular Providence, and sets aside the Events which would otherwise have been produc'd in the Course of Nature, or by the Free Agency of Man.[57] He later stated, in the Constitutional Convention, that "the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth -- that God governs in the affairs of men."[58]

For his part, Thomas Jefferson is perhaps one of the Founding Fathers with the most outspoken of Deist tendencies, though he is not known to have called himself a deist, generally referring to himself as a Unitarian. In particular, his treatment of the Biblical gospels which he titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, but which subsequently became more commonly known as the Jefferson Bible, exhibits a strong deist tendency of stripping away all supernatural and dogmatic references from the Christ story. However, Frazer, following the lead of Sydney Ahlstrom, characterizes Jefferson as not a Deist but a "theistic rationalist", because Jefferson believed in God's continuing activity in human affairs.[59][60] Frazer cites Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia, where he wrote, "I tremble" at the thought that "God is just," and he warned of eventual "supernatural influence" to abolish the scourge of slavery.[61][62]

Decline of deism

Deism is generally considered to have declined as an influential school of thought by around 1800.

After the writings of Woolston and Tindal, English deism went into slow decline. ... By the 1730s, nearly all the arguments in behalf of Deism ... had been offered and refined; the intellectual caliber of leading Deists was none too impressive; and the opponents of deism finally mustered some formidable spokesmen. The Deists of these decades, Peter Annet (1693–1769), Thomas Chubb (1679–1747), and Thomas Morgan (?–1743), are of significance to the specialist alone. ... It had all been said before, and better. .— Peter Gay, Deism: An Anthology[43]

It is probably more accurate, however, to say that deism evolved into, and contributed to, other religious movements. The term deist became rarely used, but deist beliefs, ideas, and influences remained. They can be seen in 19th-century liberal British theology and in the rise of Unitarianism, which adopted many of deism's beliefs and ideas.

Commentators have suggested a variety of reasons for the decline of classical deism.

- the rise, growth, and spread of naturalism[63] and materialism, which were atheistic

- the writings of David Hume[63][64] and Immanuel Kant[64] (and later, Charles Darwin), which increased doubt about the first cause argument and the argument from design, turning many (though not all) potential deists towards atheism instead

- criticisms (by writers such as Joseph-Marie de Maistre and Edmund Burke) of excesses of the French Revolution, and consequent rising doubts that reason and rationalism could solve all problems[64]

- deism became associated with pantheism, freethought, and atheism, all of which became associated with one another, and were so criticized by Christian apologists[63][64]

- frustration with the determinism implicit in "This is the best of all possible worlds"

- deism remained a personal philosophy and had not yet become an organized movement (before the advent in the 20th century of organizations such as the World Union of Deists)

- with the rise of Unitarianism, based on deistic principles, people self-identified as Unitarians rather than as deists[64]

- an anti-deist and anti-reason campaign by some Christian clergymen and theologians such as Johann Georg Hamann to vilify deism

- Christian revivalist movements, such as Pietism and Methodism, which taught that a more personal relationship with a deity was possible[64]

Deism today

Contemporary deism attempts to integrate classical deism with modern philosophy and the current state of scientific knowledge. This attempt has produced a wide variety of personal beliefs under the broad classification of belief of "deism".

Classical deism held that a human's relationship with God was impersonal: God created the world and set it in motion but does not actively intervene in individual human affairs but rather through divine providence. What this means is that God will give humanity such things as reason and compassion but this applies to all and not to individual intervention.

Some modern deists have modified this classical view and believe that humanity's relationship with God is transpersonal, which means that God transcends the personal/impersonal duality and moves beyond such human terms. Also, this means that it makes no sense to state that God intervenes or does not intervene, as that is a human characteristic which God does not contain. Modern deists believe that they must continue what the classical deists started and continue to use modern human knowledge to come to understand God, which in turn is why a human-like God that can lead to numerous contradictions and inconsistencies is no longer believed in and has been replaced with a much more abstract conception.

A modern definition[65] has been created and provided by the World Union of Deists (WUD) that provides a modern understanding of deism:

Deism is the recognition of a universal creative force greater than that demonstrated by mankind, supported by personal observation of laws and designs in nature and the universe, perpetuated and validated by the innate ability of human reason coupled with the rejection of claims made by individuals and organized religions of having received special divine revelation.

Because deism asserts the existence of God without accepting claims of divine revelation, it appeals to people from both ends of the religious spectrum. Antony Flew, for example, was a convert from atheism, and Raymond Fontaine was a Roman Catholic priest for over 20 years before converting.[66]

The 2001 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), which involved 50,000 participants, reported that the number of participants in the survey identifying themselves as deists grew at the rate of 717 percent between 1990 and 2001. If this were generalized to the US population as a whole, it would make deism the fastest-growing religious classification in the US for that period, with the reported total of 49,000 self-identified adherents representing about 0.02% of the US population at the time.[67][68]

Modern deistic organizations and websites

In 1993, Bob Johnson established the first Deist organization since the days of Thomas Paine and Elihu Palmer with the World Union of Deists. The WUD offered the monthly hardcopy publication THINK! Currently the WUD offers two online Deist publications, THINKonline! and Deistic Thought & Action! As well as using the Internet for spreading the Deist message, the WUD is also conducting a direct mail campaign.

1996 saw the first Web site dedicated to deism with the WUD site Deism.com. In 1998, Sullivan-County.com[69] was originally the Virginia/Tennessee affiliate of WUD and the second deism site on the Web. It split from Deism.com to promote more traditional and historical Deist beliefs and history.

The Positive Deism movement began in 2004. As has been stated above, historically and to the present day, Deists have been very critical of the revealed religions as well as trying to be constructive. Positive Deists focus their efforts solely on being constructive and avoid criticism of other faiths. In 2009 Chuck Clendenen, one of its adherents, published a book entitled "Deist: So that's what I am!". The aim of the book was to educate those who believed similarly, but did not know the words Deism and Deist, that there is a name for their belief.

In 2009, the World Union of Deists published a book on deism, Deism: A Revolution in Religion, A Revolution in You written by its founder and director, Bob Johnson. This book focuses on what deism has to offer both individuals and society. In 2010 the WUD published the book An Answer to C.S. Lewis' Mere Christianity which is a rebuttal to the book Mere Christianity by the famous Christian apologist C.S. Lewis. In 2014 the WUD published its third book, God Gave Us Reason, Not Religion which exposes the profound difference between God and religion and which promotes innate reason as God's greatest gift to humanity, other than life itself. It advances the idea that people can have belief in The Supreme Intelligence/God that is beyond a reasonable doubt.

In 2010, the Church of Deism was formed in an effort to extend the legal rights and privileges of more traditional religions to Deists while maintaining an absence of established dogma and ritual.

Subcategories of contemporary deism

Modern deists hold a wide range of views on the nature of God and God's relationship to the world. The common area of agreement is the desire to use reason, experience, and nature as the basis of belief.

There are a number of subcategories of modern deism, including monodeism (this being the default standard concept of deism), polydeism, pandeism, panendeism, spiritual deism, process deism, Christian deism, scientific deism, and humanistic deism. Some deists see design in nature and purpose in the universe and in their lives (Prime Designer). Others see God and the universe in a co-creative process (Prime Motivator). Some deists view God in classical terms and see God as observing humanity but not directly intervening in our lives (Prime Observer), while others see God as a subtle and persuasive spirit who created the world, but then stepped back to observe (Prime Mover).

Pandeism

Pandeism combines elements of deism with elements of pantheism, the belief that the universe is identical to God. Pandeism holds that God was a conscious and sentient force or entity that designed and created the universe, which operates by mechanisms set forth in the creation. God thus became an unconscious and nonresponsive being by becoming the universe. Other than this distinction (and the possibility that the universe will one day return to the state of being God), pandeistic beliefs are deistic. The earliest allusion to pandeism found to date is in 1787, in translator Gottfried Große’s interpretation of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History:

Beym. Plinius, den man, wo nicht Spinozisten, doch einen Pandeisten nennen konnte, ist Natur oder Gott kein von der Welt getrenntes oder abgesondertes Wesen. Seine Natur ist die ganze Schöpfung im Konkreto, und eben so scheint es mit seiner Gottheit beschaffen zu seyn.[70]

Here Gottfried says that Pliny is not Spinozist, but 'could be called a Pandeist' whose Nature or God 'is not a being separate from the world. Its nature is the whole creation in concrete form, and thus it seems to be designed with its divinity.' The term was used in 1859 by German philosophers and frequent collaborators Moritz Lazarus and Heymann Steinthal in Zeitschrift für Völkerpsychologie und Sprachwissenschaft. They wrote:

Man stelle es also den Denkern frei, ob sie Theisten, Pan-theisten, Atheisten, Deisten (und warum nicht auch Pandeisten?)[71]

This is translated as:

So we should let these thinkers decide themselves whether they are theists, pan-theists, atheists, deists (and why not even pandeists?)

In the 1960s, theologian Charles Hartshorne scrupulously examined and rejected both deism and pandeism (as well as pantheism) in favor of a conception of God whose characteristics included "absolute perfection in some respects, relative perfection in all others" or "AR", writing that this theory "is able consistently to embrace all that is positive in either deism or pandeism", concluding that "panentheistic doctrine contains all of deism and pandeism except their arbitrary negations".[72]

Panendeism

Panendeism combines deism with panentheism, the belief that the universe is part of God, but not all of God. A component of panendeism is "experiential metaphysics" – the idea that a mystical component exists within the framework of panendeism, allowing the seeker to experience a relationship to Deity through meditation, prayer or some other type of communion.[73] This is a major departure from classical deism.

A 1995 news article includes an early usage of the term by Jim Garvin, a Vietnam veteran who became a Trappist monk in the Holy Cross Abbey of Berryville, Virginia, and went on to lead the economic development of Phoenix, Arizona. Despite his Roman Catholic post, Garvin described his spiritual position as "pandeism' or 'pan-en-deism,' something very close to the Native American concept of the all-pervading Great Spirit..."[74]

Contemporary deist opinions on prayer

Many classical deists were critical of some types of prayer. For example, in Christianity as Old as the Creation, Matthew Tindal argues against praying for miracles, but advocates prayer as both a human duty and a human need.[75]

Today, deists hold a variety of opinions about prayer:

- Some contemporary deists believe (with the classical deists) that God has created the universe perfectly, so no amount of supplication, request, or begging can change the fundamental nature of the universe.

- Some deists believe that God is not an entity that can be contacted by human beings through petitions for relief; rather, God can only be experienced through the nature of the universe.

- Some deists do not believe in divine intervention, but still find value in prayer as a form of meditation, self-cleansing, and spiritual renewal. Such prayers are often appreciative (that is, "Thank you for ...") rather than supplicative (that is, "Please, God, grant me ...").[76]

- Some deists practice meditation and make frequent use of Affirmative Prayer, a non-supplicative form of prayer which is common in the New Thought movement.

Recent discussion of the role of deism

Charles Taylor, in his 2007 book A Secular Age, showed the historical role of deism, leading to what he calls an exclusive humanism. This humanism invokes a moral order, whose ontic commitment is wholly intra-human, with no reference to transcendence.[77] One of the special achievements of such deism-based humanism is that it discloses new, anthropocentric moral sources by which human beings are motivated and empowered to accomplish acts of mutual benefit.[78] This is the province of a buffered, disengaged self, which is the locus of dignity, freedom and discipline, and is endowed with a sense of human capability.[79] According to Taylor, by the early 19th century this deism-mediated exclusive humanism developed as an alternative to Christian faith in a personal God and an order of miracles and mystery.

See also

- Agnosticism

- American Enlightenment

- Avatar

- Ceremonial deism

- Christian deism

- Deism in England and France in the 18th century

- Deity

- Ietsism

- Infinitism

- List of deists

- Polydeism

- Religious affiliations of Presidents of the United States

- Spiritual entities

- Theistic evolution

- Transcendentalism

- Unitarian Universalism

References

- ↑ US dict: dē′·ĭzm. R. E. Allen (ed) (1990). The Concise Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Deist – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ↑ "Deism". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2012.

In general, Deism refers to what can be called natural religion, the acceptance of a certain body of religious knowledge that is inborn in every person or that can be acquired by the use of reason and the rejection of religious knowledge when it is acquired through either revelation or the teaching of any church.

- ↑ "Deism". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

DEISM: A system of belief that posits God's existence as the cause of all things, and admits His perfection, but rejects Divine revelation and government, proclaiming the all-sufficiency of natural laws.

- ↑ Aveling, Francis, ed. (1908). "Deism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

The deists were what nowadays would be called freethinkers, a name, indeed, by which they were not infrequently known; and they can only be classed together wholly in the main attitude that they adopted, viz. in agreeing to cast off the trammels of authoritative religious teaching in favour of a free and purely rationalistic speculation.... Deism, in its every manifestation was opposed to the current and traditional teaching of revealed religion.

- ↑ "Webster's 1828 Dictionary". 1828. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

The doctrine or creed of a deist; the belief or system of religious opinions of those who acknowledge the existence of one God, but deny revelation: or deism is the belief in natural religion only, or those truths, in doctrine and practice, which man is to discover by the light of reason, independent and exclusive of any revelation from God. Hence deism implies infidelity or a disbelief in the divine origin of the scriptures.

- ↑ "Deism". The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. 2011. doi:10.1002/9780470670606.wbecc0408/abstract.

Deism is a rationalistic, critical approach to theism with an emphasis on natural theology. The Deists attempted to reduce religion to what they regarded as its most foundational, rationally justifiable elements. Deism is not, strictly speaking, the teaching that God wound up the world like a watch and let it run on its own, though that teaching was embraced by some within the movement.

- ↑ Thomsett, Michael C. (2011). Heresy in the Roman Catholic Church: A History. McFarland. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-7864-8539-0. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- 1 2 Wilson, Ellen Judy; Reill, Peter Hanns (2004). Deism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-8160-5335-3. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ↑ Hardwick, J. "Modern Deism". J. Hardwick. Retrieved 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ James W. Sire (2009). The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalog. InterVarsity Press. pp. 59–64.

- ↑ "Deism". The Encyclopedia Britannica. 2015. Retrieved 2015.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the word Deism was used by some theologians in contradistinction to theism, the belief in an immanent God who actively intervenes in the affairs of men. In this sense, Deism was represented as the view of those who reduced the role of God to a mere act of creation in accordance with rational laws discoverable by man and held that, after the original act, God virtually withdrew and refrained from interfering in the processes of nature and the ways of man. So stark an interpretation of the relations of God and man, however, was accepted by very few Deists during the flowering of the doctrine, though their religious antagonists often attempted to force them into this difficult position.

Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ↑ Wingate, T. "The True and False Definitions of Deism". Deism.com. Retrieved 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 Justo L. González (1984). The Reformation to the present day. HarperCollins. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-06-063316-5. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ Joseph C. McLelland; Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion (November 1988). Prometheus rebound: the irony of atheism. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-88920-974-9. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ James E. Force; Richard Henry Popkin (1990). Essays on the context, nature, and influence of Isaac Newton's theology. Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7923-0583-5. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ "Deism Defined". Moderndeism.com. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. Eerdmans. p. 13.

- 1 2 See the entry for "Deism" in the on-line Dictionary of the History of Ideas.

- 1 2 Waring, E. Graham (1967). Deism and Natural Religion: A Source Book. Introduction, p. xv.

- ↑ Willey, Basil (1940). The Eighteenth Century Background. p. 11.

- ↑ Waring, E. Graham (1967). Deism and Natural Religion: A Source Book. p. 113.

- ↑ Quoted in Deism and Natural Religion: A Source Book, pp. 1–12

- ↑ Champion, J.A.I. (2014). The Pillars of Priestcraft Shaken: The Church of England and its Enemies, 1660-1730. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History). Champion maintains that historical argument was a central component of the Deists's defences of what they considered true religion.

- ↑ Waring, Edward Graham (1967). Deism and natural religion: a source book. F. Ungar Pub. Co. p. 163. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ↑ David Hartley, for example, described himself as "quite in the necessitarian scheme. See Ferg, Stephen, "Two Early Works of David Hartley", Journal of the History of Philosophy, vol. 19, no. 2 (April 1981), pp. 173–89.

- ↑ See for example Liberty and Necessity (1729).

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. Eerdmans. p. 137.

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. Eerdmans. p. 134.

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. Eerdmans. p. 78.

- ↑ Michael E. Eidenmuller. "Benjamin Franklin – Constitutional Convention Address on Prayer". Americanrhetoric.com. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ The discussion of the background of deism is based on the excellent summary in "The Challenge of the Seventeenth Century" in The Historical Jesus Question by Gregory W. Dawes (Westminster: John Knox Press, 2001). Good discussions of individual deist writers can be found in The Seventeenth Century Background and The Eighteenth Century Background by Basil Willey.

- ↑ "Windows into China", John Parker, p.25, ISBN 0-89073-050-4

- ↑ "The Eastern origins of Western civilization", John Hobson, p194-195, ISBN 0-521-54724-5

- ↑ Willey, Basil (1934). The Seventeenth Century Background.

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. pp. 59 ff.

- ↑ Herbert, The Life of Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury (Dublin, 1771), 244–245, as cited in Waligore p. 189.

- ↑ Gay, Peter (1968). Deism: An Anthology. Van Nostrand. pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. Eerdmans. pp. 96–99.

- 1 2 Gay, Peter (1968). Deism: An Anthology. Van Nostrand. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Gay, Peter (1968). Deism: An Anthology. Van Nostrand. pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Waring, Edward Graham (1967). Deism and natural religion: a source book. F. Ungar Pub. Co. p. 107. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- 1 2 Gay, Peter (1968). Deism: An Anthology. Van Nostrand. p. 140.

- ↑ Orr, John (1934). English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits. Eerdmans. p. 173.

- ↑ Russell, Paul (2005). "Hume on Religion". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ Gay, Peter (1968). Deism: An Anthology. Van Nostrand. p. 143.

- ↑ "Excerpts from Allen's Reason The Only Oracle Of Man". Ethan Allen Homestead Museum.

- ↑ "Culture Wars in the Early Republic". Common-place.

- ↑ Walters, Kerry S. (1992). Rational Infidels: The American Deists. Durango, CO: Longwood Academic. ISBN 0-89341-641-X.

- ↑ "The Deist Minimum". First Things. 2005.

- ↑ Holmes, David (2006). The Faiths of the Founding Fathers. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-530092-0.

- ↑ David Liss (11 June 2006). "The Founding Fathers Solving modern problems, building wealth and finding God". Washington Post.

- ↑ Gene Garman (2001). "Was Thomas Jefferson a Deist?". Sullivan-County.com.

- ↑ Walter Isaacson (March–April 2004). "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life". Skeptical Inquirer.

- ↑ Franklin, Benjamin (2005). Benjamin Franklin: Autobiography, Poor Richard, and Later Writings. New York, NY: Library of America. p. 619. ISBN 1-883011-53-1.

- ↑ "Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography". University of Maine, Farmington.

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin, On the Providence of God in the Government of the World (1730).

- ↑ Max Farrand, ed. (1911). The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787. 1. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 451.

- ↑ Frazer, Gregg L. (2012). The Religious Beliefs of America's Founders: Reason, Revelation, Revolution. University Press of Kansas. p. 11.

- ↑ Ahlstrom, Sydney E. (2004). A Religious History of the American People. p. 359.

- ↑ Frazer, Religious Beliefs of America's Founders, p. 128 quoting Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia, 1800 ed., p. 164.

- ↑ Other scholars call Jefferson a "theistic rationalist" (although that term was coined later), such as Gary Scott Smith (2006). Faith and the Presidency: From George Washington to George W. Bush. Oxford U.P. p. 69. ISBN 9780198041153.

- 1 2 3 "English Deism". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2006. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mossner, Ernest Campbell (1967). "Deism". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2. Collier-MacMillan. pp. 326–336.

- ↑ "Deism Defined".

- ↑ "Raymond Fontaine's website: From Catholic Priest to Deist With Nature's God". deism.com.

- ↑ "ARIS key findings, 2001".

- ↑ "Largest Religious Groups in the United States of America". Adherents.com.

- ↑ "Deism and Reason". Sullivan-county.com. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ Große, Gottfried (1787). Naturgeschichte: mit erläuternden Anmerkungen. p. 165.

- ↑ Moritz Lazarus and Heymann Steinthal, Zeitschrift für Völkerpsychologie und Sprachwissenschaft (1859), p. 262.

- ↑ Hartshorne, Charles (1964). Man's Vision of God and the Logic of Theism. p. 348. ISBN 0-208-00498-X.

- ↑ "Welcome to". Panendeism.com. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ Albuquerque Journal, Saturday, November 11, 1995, B-10.

- ↑ External link to portion of text

- ↑ "Deism Defined, Welcome to Deism, Deist Glossary and Frequently Asked Questions". Deism.com. 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ Taylor, C (2007). A Secular Age. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 256.

- ↑ Taylor, C (2007). A Secular Age. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 257.

- ↑ Taylor, C (2007). A Secular Age. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 262.

Bibliography

| Look up deism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Deism |

Histories

- An Age of Infidels: The Politics of Religious Controversy in the Early United States by Eric R. Schlereth (University of Pennsylvania Press; 2013) 295 pages; on conflicts between deists and their opponents.

- Herrick, James A. (1997). The Radical Rhetoric of the English Deists: The Discourse of Skepticism, 1680–1750. University of South Carolina Press.

- English Deism: Its Roots and Its Fruits by John Orr (1934)

- European Thought in the Eighteenth Century by Paul Hazard (1946, English translation 1954)

- Early Deism in France: From the so-called 'deistes' of Lyon (1564) to Voltaire's 'Lettres philosophiques' (1734) by C. J. Betts (Martinus Nijhoff, 1984)

- The Seventeenth Century Background: Studies on the Thought of the Age in Relation to Poetry and Religion by Basil Willey (1934)

- The Eighteenth Century Background: Studies on the Idea of Nature in the Thought of the Period by Basil Willey (1940)

- Simon Tyssot de Patot and the Seventeenth-Century Background of Critical Deism by David Rice McKee (Johns Hopkins Press, 1941)

- The Historical Argument for the Resurrection of Jesus During the Deist Controversy by William Lane Craig (Edwin Mellen, 1985)

- Deism, Masonry, and the Enlightenment. Essays Honoring Alfred Owen Aldridge. Ed. J. A. Leo Lemay. Newark, University of Delaware Press, 1987.

Primary sources

- Paine, Thomas (1795). The Age of Reason.

- Palmer, Elihu. The Principles of Nature.

- Deism: A Revolution in Religion, A Revolution in You.

- An Answer to C.S. Lewis' Mere Christianity.

- God Gave Us Reason, Not Religion.

- Deism: An Anthology by Peter Gay (Van Nostrand, 1968)

- Deism and Natural Religion: A Source Book by E. Graham Waring (Frederick Ungar, 1967)

- The American Deists: Voices of Reason & Dissent in the Early Republic by Kerry S. Walters (University of Kansas Press, 1992), which includes an extensive bibliographic essay