Jefferson Bible

|

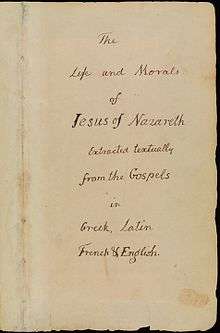

The title page of the Jefferson Bible written in Jefferson's hand. Reads, "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth Extracted Textually from the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French & English" | |

| Material | Red Morocco goatskin leather, handmade wove paper, iron gall ink |

|---|---|

| Size | 21.2 cm x 13.2 cm x 3.4 cm |

| Writing | Greek, Latin, French, and English |

| Created | Approx. 1819, Monticello |

| Discovered | Acquired by the Smithsonian in 1895 |

| Present location | Smithsonian National Museum of American History |

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, commonly referred to as the Jefferson Bible, was a book constructed by Thomas Jefferson in the later years of his life by cutting and pasting with a razor and glue numerous sections from the New Testament as extractions of the doctrine of Jesus. Jefferson's condensed composition is especially notable for its exclusion of all miracles by Jesus and most mentions of the supernatural, including sections of the four gospels that contain the Resurrection and most other miracles, and passages that portray Jesus as divine.[1][2][3][4]

Early draft

In an 1803 letter to Joseph Priestley, Jefferson stated that he conceived the idea of writing his view of the "Christian System" in a conversation with Dr. Benjamin Rush during 1798–99. He proposes beginning with a review of the morals of the ancient philosophers, moving on to the "deism and ethics of the Jews," and concluding with the "principles of a pure deism" taught by Jesus, "omitting the question of his deity." Jefferson explains that he does not have the time, and urges the task on Priestley as the person best equipped to accomplish the task.[5]

Jefferson accomplished a more limited goal in 1804 with The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth, the predecessor to The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.[6] He described it in a letter to John Adams dated October 13, 1813:

In extracting the pure principles which he taught, we should have to strip off the artificial vestments in which they have been muffled by priests, who have travestied them into various forms, as instruments of riches and power to themselves. We must dismiss the Platonists and Plotinists, the Stagyrites and Gamalielites, the Eclectics, the Gnostics and Scholastics, their essences and emanations, their logos and demiurges, aeons and daemons, male and female, with a long train of … or, shall I say at once, of nonsense. We must reduce our volume to the simple evangelists, select, even from them, the very words only of Jesus, paring off the amphibologisms into which they have been led, by forgetting often, or not understanding, what had fallen from him, by giving their own misconceptions as his dicta, and expressing unintelligibly for others what they had not understood themselves. There will be found remaining the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man. I have performed this operation for my own use, by cutting verse by verse out of the printed book, and arranging the matter which is evidently his, and which is as easily distinguishable as diamonds in a dunghill. The result is an octavo of forty-six pages, of pure and unsophisticated doctrines.[5]

Jefferson wrote that “Jesus did not mean to impose himself on mankind as the son of God.” He called the writers of the New Testament “ignorant, unlettered men” who produced “superstitions, fanaticisms, and fabrications.” He called the Apostle Paul the “first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus.” He dismissed the concept of the Trinity as “mere Abracadabra of the mountebanks calling themselves the priests of Jesus.” He believed that the clergy used religion as a “mere contrivance to filch wealth and power to themselves” and that “in every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty.” And he wrote in a letter to John Adams that “the day will come when the mystical generation of Jesus, by the supreme being as his father in the womb of a virgin, will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the brain of Jupiter.”

Jefferson never referred to his work as a Bible, and the full title of this 1804 version was, The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth, being Extracted from the Account of His Life and Doctrines Given by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John; Being an Abridgement of the New Testament for the Use of the Indians, Unembarrased [uncomplicated] with Matters of Fact or Faith beyond the Level of their Comprehensions.[7]

Jefferson frequently expressed discontent with this earlier version. The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth represents the fulfillment of his desire to produce a more carefully assembled edition.

Content

Using a razor and glue, Jefferson cut and pasted his arrangement of selected verses from the King James Version[8] of the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in chronological order—putting together excerpts from one text with those of another to create a single narrative. Thus he begins with Luke 2 and Luke 3, then follows with Mark 1 and Matthew 3. He provides a record of which verses he selected, and of the order he chose in his Table of the Texts from the Evangelists employed in this Narrative and of the order of their arrangement.

Consistent with his naturalistic outlook and intent, most supernatural events are not included in Jefferson's heavily edited compilation. Paul K. Conkin states that "For the teachings of Jesus he concentrated on his milder admonitions (the Sermon on the Mount) and his most memorable parables. What resulted is a reasonably coherent, but at places oddly truncated, biography. If necessary to exclude the miraculous, Jefferson would cut the text even in mid-verse."[9] Historian Edwin Scott Gaustad explains, "If a moral lesson was embedded in a miracle, the lesson survived in Jeffersonian scripture, but the miracle did not. Even when this took some rather careful cutting with scissors or razor, Jefferson managed to maintain Jesus' role as a great moral teacher, not as a shaman or faith healer."[10]

Therefore, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth begins with an account of Jesus’s birth without references to angels (at that time), genealogy, or prophecy. Miracles, references to the Trinity and the divinity of Jesus, and Jesus' resurrection are also absent from his collection.[11]

No supernatural acts of Christ are included at all in this regard, while the few things of a supernatural nature include receiving of the Holy Spirit,[12] angels,[13] Noah's Ark and the Great Flood,[14] the Tribulation,[15] the Second Coming,[16] the resurrection of the dead,[17] a future kingdom,[16][18] and eternal life,[19] Heaven,[20] Hell[21] and punishment in everlasting fire, the Devil,[22] and the soldiers falling backwards to the ground in response to Jesus stating, "I am he."[23]

Rejecting the resurrection of Jesus, the work ends with the words: "Now, in the place where He was crucified, there was a garden; and in the garden a new sepulchre, wherein was never man yet laid. There laid they Jesus. And rolled a great stone to the door of the sepulchre, and departed." These words correspond to the ending of John 19 in the Bible.

Purpose

It is understood by some historians that Jefferson composed it for his own satisfaction, supporting the Christian faith as he saw it. Gaustad states, "The retired President did not produce his small book to shock or offend a somnolent world; he composed it for himself, for his devotion, for his assurance, for a more restful sleep at nights and a more confident greeting of the mornings." [24]

There is no record of this or its successor being for "the Use of the Indians," despite the stated intent of the 1804 version being that purpose. Although the government long supported Christian activity among Indians,[25][26] and in Notes on the State of Virginia Jefferson supported "a perpetual mission among the Indian tribes," at least in the interest of anthropology,[27] and as President sanctioned financial support for a priest and church for the Kaskaskia Indians,[28] Jefferson did not make these works public. Instead, he acknowledged the existence of The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth to only a few friends, saying that he read it before retiring at night, as he found this project intensely personal and private.[29]

Ainsworth Rand Spofford, Librarian of Congress (1864–1894) stated: "His original idea was to have the life and teachings of the Saviour, told in similar excerpts, prepared for the Indians, thinking this simple form would suit them best. But, abandoning this, the formal execution of his plan took the shape above described, which was for his individual use. He used the four languages that he might have the texts in them side by side, convenient for comparison. In the book he pasted a map of the ancient world and the Holy Land, with which he studied the New Testament." [30]

Some speculate that the reference to "Indians" in the 1804 title may have been an allusion to Jefferson's Federalist opponents, as he likewise used this indirect tactic against them at least once before, that being in his second inaugural address. Or that he was providing himself a cover story in case this work became public.[31]

Also referring to the 1804 version, Jefferson wrote, "A more beautiful or precious morsel of ethics I have never seen; it is a document in proof that I am a real Christian, that is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus."[30]

Jefferson's claim to be a Christian was made in response to those who accused him of being otherwise, due to his unorthodox view of the Bible and conception of Christ. Recognizing his rather unusual views, Jefferson stated in a letter (1819) to Ezra Stiles Ely, "You say you are a Calvinist. I am not. I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know."[32]

Publication history

After completion of the Life and Morals, about 1820, Jefferson shared it with a number of friends, but he never allowed it to be published during his lifetime.

The most complete form Jefferson produced was inherited by his grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, and was published in 1895 by the National Museum in Washington. The book was later published as a lithographic reproduction by an act of the United States Congress in 1904. Beginning in 1904 and continuing every other year until the 1950s, new members of Congress were given a copy of the Jefferson Bible. Until the practice first stopped, copies were provided by the Government Printing Office. A private organization, the Libertarian Press, revived the practice in 1997.[33][34]

In January 2013, the American Humanist Association published an edition of the Jefferson Bible, distributing a free copy to every member of Congress and President Barack Obama.[35] A Jefferson Bible For the Twenty-First Century adds samples of passages that Jefferson chose to omit, as well as examples of the "best" and "worst" from the Hebrew Bible, the Quran, the Bhagavad Gita, the Buddhist Sūtras, and the Book of Mormon.[36]

The Smithsonian published the first full-color facsimile[37] of the Jefferson Bible on November 1, 2011. Released in tandem with a Jefferson Bible exhibit at the National Museum of American History, the reproduction features introductory essays by Smithsonian Political History curators Harry R. Rubenstein and Barbara Clark Smith, and Smithsonian Senior Paper Conservator Janice Stagnitto Ellis. The book's pages were digitized using a Hasselblad H4D50-50 megapixel DSLR camera and a Zeiss 120 macro lens, and were photographed by Smithsonian photographer, Hugh Talman.[38]

The entire Jefferson Bible is available to view, page-by-page, on the Smithsonian National Museum of American History's website.[39] The high-resolution digitization enables the public to see the minute details and anomalies of each page.

The text is in the public domain and freely available on the Internet.

Recent history

In 1895, the Smithsonian Institution under the leadership of librarian Cyrus Adler purchased the original Jefferson Bible from Jefferson's great-granddaughter Carolina Randolph for $400. A conservation effort commencing in 2009, led by Senior Paper Conservator Janice Stagnitto Ellis,[40] in partnership with the museum's Political History department, allowed for a public unveiling in an exhibit open from November 11, 2011, through May 28, 2012, at the National Museum of American History. Also displayed were the source books from which Jefferson cut his selected passages, and the 1904 edition of the Jefferson Bible requested and distributed by the United States Congress.[37] The exhibit was accompanied by an interactive digital facsimile available on the museum's public website. On February 20, 2012, the Smithsonian Channel premiered the documentary Jefferson's Secret Bible.[37]

- The Jefferson Bible at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Fold-out tab Jefferson glued in the margin of page 56

Fold-out tab Jefferson glued in the margin of page 56 Jefferson textually corrects "out" into "up"

Jefferson textually corrects "out" into "up" Jefferson extracts the word "as" from a sentence, to avoid three prepositions in a row

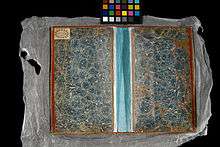

Jefferson extracts the word "as" from a sentence, to avoid three prepositions in a row Marbled paper inside the book's covers

Marbled paper inside the book's covers

Editions in print

- Facsimile

- The Jefferson Bible, Smithsonian Edition: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (2011) Smithsonian Books hardcover: ISBN 978-1-58834-312-3

- "Jefferson's Extracts from the Gospels: 'The Philosophy of Jesus' and 'The Life and Morals of Jesus': THE PAPERS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON: SECOND SERIES" (1983) Princeton University Press hardcover: ISBN 0-691-04699-9, paperback: ISBN 0-691-10210-4

- "THE Jefferson Bible" (1964) Clarkston N. Potter, Inc hardcover: LOC Number: 64-19900

- "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth" (1904) United States Government Printing Office

- Text

- "The Jefferson Bible: What Thomas Jefferson Selected as the Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth": ISBN 978-1-936583-21-8

- The Jefferson Bible: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (2006) Dover Publications paperback: ISBN 0-486-44921-1

- The Jefferson Bible, (2006) Applewood Books hardcover: ISBN 1-55709-184-6

- The Jefferson Bible, introduction by Cyrus Adler, (2005) Digireads.com paperback: ISBN 1-4209-2492-3

- The Jefferson Bible, introduction by Percival Everett, (2004) Akashic Books paperback: ISBN 1-888451-62-9

- The Jefferson Bible, introduction by M. A. Sotelo, (2004) Promotional Sales Books, LLC paperback

- Jefferson’s "Bible": The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, introduction by Judd W. Patton, (1997) American Book Distributors paperback: ISBN 0-929205-02-2

- A Jefferson Bible for the Twenty-First Century, 2013, Humanist Press, paperback ISBN 978-0-931779-29-9, ebook ISBN 978-0-931779-30-5

See also

- The Age of Reason

- Bibliography of Thomas Jefferson

- Jesuism

- The Jesus Seminar

- Rationalism

- Thomas Jefferson and religion

- Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

References

- ↑ R.P. Nettelhorst. "Notes on the Founding Fathers and the Separation of Church and State". Quartz Hill School of Theology. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Lipscomb, 10:376-377.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson's Abridgement of the Words of Jesus of Nazareth (Charlotesville: Mark Beliles, 1993), 14.

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Lipscomb, 10:232-233.

- 1 2 Excerpts from the Correspondence of Thomas Jefferson Retrieved March 30, 2007

- ↑ Unitarian Universalist Historical Society profile of Jefferson. Retrieved March 30, 2007

- ↑ Randal, Henry S., The Life of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 3 (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1858), 654.

- ↑ Jefferson Bible Angelfire.com

- ↑ Paul K. Conkin, quoted in Jeffersonian Legacies, edited by Peter S. Onuf, p. 40

- ↑ Edwin Scott Gaustad, Sworn on the Altar of God: A Religious Biography of Thomas Jefferson, p 129

- ↑ Reece, Erik (December 1, 2005). "Jesus Without The Miracles – Thomas Jefferson's Bible and the Gospel of Thomas". Harper's Magazine, v. 311, n. 1867.

- ↑ "The Book, Page 40 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 42 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 64 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 63 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- 1 2 "The Book, Page 67 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 59 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 39 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 37 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 62 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 46 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 68 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "The Book, Page 73 - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ Sworn on the Altar of God: A Religious Biography of Thomas Jefferson, p. 131

- ↑ American Indians and Christianity Oklahoma Historical Society

- ↑ Library of Congress exhibit, American Indians of the Pacific Northwest

- ↑ Jefferson's Notes on Virginia, University of Virginia Library, p. 210

- ↑ TREATY WITH THE KASKASKIA, 1803

- ↑ Smithsonian magazine, Secretary Clough on Jefferson's Bible, October 2011

- 1 2 Cyrus Adler, Introduction to the Jefferson Bible

- ↑ Forrest Church, The Jefferson Bible: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, p. 20

- ↑ Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Ezra Stiles Ely, June 25, 1819, Encyclopedia Virginia

- ↑ Hitchens, Christopher (January 9, 2007). "What Jefferson Really Thought About Islam". Slate. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ↑ "Writing".

- ↑ "Humanists slice and dice the world's sacred texts - Religion News Service". Religion News Service.

- ↑ "Humanists Create New 'Jefferson Bible;' Deliver Copies to Obama, Congress". Christian Post.

- 1 2 3 G. Wayne Clough (October 2011). "Secretary Clough on Jefferson's Bible". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas (2011). The Jefferson Bible, Smithsonian Edition: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-58834-312-3.

- ↑ "Thomas Jefferson's Bible - The Jefferson Bible, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution".

- ↑ "History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places - Smithsonian".

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jefferson Bible. |

- Official Smithsonian Jefferson Bible website: "Thomas Jefferson's Bible" – at National Museum of American History

- Online text of the Jefferson Bible: Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth – at University of Virginia Library

- Online text: The Jefferson Bible: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, Extracted From The Four Gospels; Originally Compiled by Thomas Jefferson; Edited by Charles M. Province United Christ Church Ministry

- Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth – at Google Books

- "Jefferson's Religious Beliefs". Monticello.org. Retrieved Sep 26, 2012.

- Thomas Jefferson and his Bible from Frontline

- The two copies of the Bible that Jefferson cut up to make the book reside at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia