Solun-Voden dialect

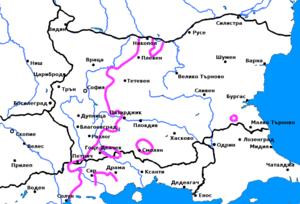

The Solun-Voden dialect,[1] Lower Vardar dialect,[2] or Kukush-Voden dialect[3] is a South Slavic dialect spoken in parts of the Greek periphery of Central Macedonia, and the vicinity of Gevgelija and Dojran in the Republic of Macedonia. It has been treated as part of both Macedonian[4] and Bulgarian[3] dialectology.

Dialect area

The dialect is named after Slavic toponyms for the cities of Thessaloniki (Solun), Edessa (Voden) and Kilkis (Kukush), or after the river Vardar. In terms of Macedonian dialectology, the dialect is classified as a member of the south-eastern subgroup of the Eastern and Southern group of Macedonian dialects,[5] spoken in an area that also covers Veria, Giannitsa,[6] and the towns of Dojran and Gevgelija in the Republic of Macedonia.[5]

In terms of Bulgarian dialectology,[3] Solun dialect is a separate Eastern Bulgarian dialect, spoken in the northern part of today's Thessaloniki regional unit in Greece. Solun and Drama-Ser dialects are grouped as western Rup dialects, part of the large Rup dialect massif of Rhodopes and Thrace which are transitional between the Western and Eastern Bulgarian dialects.[3] The dialect spoken around Voden and Kukush as well as in the region of the Lower Vardar to the west of Thessaloniki is characterized as Western Bulgarian Kukush-Voden dialect,[3] which shows some connections with Eastern Bulgarian dialects like the reduction and absorption of unstressed vowels and retention of the sound x /x/.[7]

Suho-Visoka sub-dialect

The Suho-Visoka sub-dialect is spoken in and around the city of Salonika. The dialect is also found in the town of Lagkadas. The dialect is best preserved in the villages of Sochos (Сухо, Suho), Osa (Висока, Visoka), Nikopoli (Зарово, Zarovo), Xylopoli (Негован, Negovan), Levchohori (Клепе, Klepe), Klisali (Клисали, Klisali) and Assiros (Гвоздово, Gvozdovo). The subdialect has been referred to as Bogdanski Govor (Macedonian: Богдански говор), in reference to its position on the "Bogdan" mountain.

One of the first researchers of the Slavic dialects in this part of Macedonia, Slovenian linguist Vatroslav Oblak described the historical development of the Bulgarian phonology and morphology, based mainly on the dialect of Suho and the adjoining area. He noted that the villages Suho, Zarovo and Visoka formed a center of nasalization.[8]

Phonological characteristics

|

Civil War experiences

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

- Retention of Proto-Slavic nasal vowels (Solun dialect in the region north-east of Solun): rə ̃kа[9] (mk:raka, bg:rəka), skɤ ̃p (mk:skap, bg:skɤp), pɛ ̃tuk (mk:pɛtok, bg:pɛtək), tʃɛ ̃du (bg, mk:tʃɛdo).

- Retention of vowels ɤ (stressed) or ə (unstressed) which come from Old Church Slavonic ѫ: vəʒa (bg:vəʒɛ), vətuk (bg:vətɤk), gɤska (bg:gɤska), dəɡa (bg:dəga), zəbi (bg:zəbi), mɤka (bg:mɤka), mɤʃ (bg:mɤʒ), pɤrt (bg:prɤt), pɤt (bg:pɤt), prɤtʃki (bg:prɤtʃki), sɤbuta (bg:sɤbɔta), ɡəsɔk (bg:ɡəsɔk), ɡəsɛnitsa (bg:ɡəsɛnitsa), mɤtɛnitsa (bg:mɤtɛnitsa). Less often the vowel u occurs instead of ɤ: kuca (bg:kɤʃta, mk:kuca), kusa (bg:kɤsa), pupka (bg:pɤpka).

- Vowel ɔ replaces Old Church Slavonic ъ: bɔtʃva (bg:bɤtʃva), vɔpka, vɔʃka (bg:vɤʃka), dɔʃ (bg:dɤʒd), zɔlva (bg:zɤlva), sɔn (bg:sɤn), takɔf (bg:takɤv), vətɔk (bg:vətɤk), vɔsɔk (bg:vɔsək)(but also: vətuk, vɔsuk).

- A very important characteristic is the reduction of the wide (unstressed) vowels. This occurs most often in the middle or the beginning of words: ɔ reduces to u — udinitsa (bg:vɔdɛnitsa), mutuvilka (bg:mɔtɔvilka), tutʃilo (bg:tɔtʃilo), usnɔva (bg:ɔsnɔva), uftʃar (bg:ɔvtʃar), usten (bg:ɔsten), utset (bg:ɔtset); ɛ reduces to i — zilɛn, pitɛl, nɛbitɔ, dɛvir, ʒɛnin, molits; a reduces to ə — pəzartʃin, pəspal, kɔmər, kɔkəl, tʃɤrgəta, mandrəta. In some morphological categories this reduction develops further into absorption of the unstressed wide vowels: ɔktɔ (bg:ɔkɔtɔ), litstɔ (bg:litsɛtɔ), duvitsta (bg:vdɔvitsata), grədinta (bg:gradinata), tuvarmɛ (bg:tɔvarimɛ), tuvartɛ (bg:tɔvaritɛ), katʃmɛ (bg:katʃimɛ).

- Generally, the consonant x is retained: in the end of words — vlax, grax, urɛx, strax, sux, vərnax, kəʒax, nusix; in the middle of words — muxlɛsinu, təxtəbita, boxtʃa, sɛdɛxa, bixa, tərtʃaxa. However, in the beginning of words /x/ is often omitted: arnɔ, arman, iʎada, itʃ, ɔrɔ, lɛp.

- The palatals c, jc, ɟ, jɟ predominate over the Old Church Slavonic diphthongs ʃt and ʒd : nɔc, cɛrka, prifacum, nejcum, lɛjca (mk:lɛca, bg:lɛʃta), sfɛjca (mk:svɛca, bg:svɛʃt), plajcaʃɛ (mk: placaʃɛ, bg:plaʃtaʃɛ); vɛɟi (mk:vɛɟi, bg:vɛʒdi), mɛɟa, saɟa, miɟu, mɛjɟa, sajɟi. In some cases, however, the diphthongs ʃt, ʒd are retained: gaʃti, lɛʃta, guvɛʒdo, prɛʒda.

- Relatively unpredictable stress. Often the stress is on the penult, but there are words which have stress placed on different syllables.[10]

Morphological characteristic

- Definite article -ut, -u for masculine gender: vratut, dɛput, zɛtut, sɔnut, sinut, krumidut, nərodut, ubrazut; ɔginu, guʃtəru, vɛtɛru.

- Definite article -to for plural: bugərɛto, kamənɛto, tsigajnɛto, vulɔvɛto, kojnɛto.

- A single common suffix -um for all three verb present tense conjugations: ɔrum, tsɛpum, pasum, vikum, glɛdum, brɔjum.

- Suffix -m for 1st person singular present tense: pijum, stojum, jadum, ɔdum.

Other specific characteristics

- Enclitic at the beginning of the sentence: Mu gɔ klava petʃatut. Si ja goreʃe furnata.

- Single short form mu for masculine, neutral, feminine, and plural pronouns: Na baba ce mu nɔsum da jədɛ (I'll take something for my grandma to eat). Na starite mu ɛ mɤtʃnɔ (It is hard for old people). Na nih mu davum jadɛjne (I give it/him/them a meal).

- Use of the preposition u instead of the preposition vo :vo selo → u selo (in village)

- Use of the preposition ut instead of ot : ut Solun → od Solun (from/of Solun). This is because ɔ in ɔt when combined with the next word becomes a wide (unstressed) vowel which undergoes reduction (see Phonological characteristics).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Typical Words

- ʒarba (bg,mk:ʒaba) - frog

- ʃarino (bg,mk:ʃareno) - coloured

- kutʃja (bg,mk:kutʃɛ) - dog

- kɤʃta (bg:kɤʃta, mk:kuќa) - house

- druguʃ (bg:drug pɤt, mk:drug pat) - another time

- vɔpka

References

- ↑ [author missing] Фонолошкиот и прозодискиот систем на говорот на селото Негован (Солунско). ПрилОЛЛН, МАНУ, 1991, XVI, 2, стр. 15-32.

- ↑ Romanski, St. Долновардарският говор. — Мак. преглед, 1932, № 1, 99—140

- 1 2 3 4 5 Стойков (Stoykov), Стойко (2002) [1962]. Българска диалектология (Bulgarian dialectology) (in Bulgarian). София: Акад. изд. "Проф. Марин Дринов". ISBN 954-430-846-6. OCLC 53429452.

- ↑ Božidar Vidoeski, Фонолошкиот систем на говорот на селото Чеган (Воденско): инвентар на фонолошките единици. МЈ, 1978, XXIX, стр. 61-73.

- 1 2 Бојковска, Стојка; Лилјана Минова - Ѓуркова, Димитар Пандев, Живко Цветковски (December 2008). Саветка Димитрова, ed. Општа граматика на македонскиот јазик (in Macedonian). Скопје: АД Просветно Дело. OCLC 888018507. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ [author missing]. Акцентските системи во македонските дијалекти во Грција (Еѓејска Македонија) и Јужна Албанија. МЈ, 1985-1986, XXXVI-XXXVII, стр. 19-45.

- ↑ Mladenov, Stefan. Geschichte der bulgarischen Sprache, Berlin-Leipzig, 1929, § 209.

- ↑ Облакъ, Ватрославъ (1894). "Приносъ къмъ българската граматика" (PDF). Сборникъ за народни умотворения, наука и книжнина. XI: 517–519. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ↑ All examples are in IPA transcription, see Ternes, Elmar; Tatjana Vladimirova-Buhtz (1999). "Bulgarian". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–57. ISBN 0-521-63751-1. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ↑ Шклифов, Благой и Екатерина Шклифова, Български диалектни текстове от Егейска Македония, София 2003, с. 18 (Shklifov, Blagoy and Ekaterina Shklifova. Bulgarian dialect texts from Aegean Macedonia Sofia 2003, p. 18)