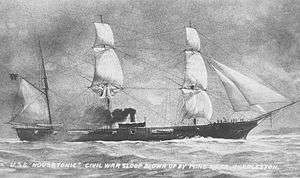

Sinking of USS Housatonic

| Sinking of USS Housatonic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

The Hunley by George S. Cook. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charles W. Pickering | George E. Dixon | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 sloop-of-war | 1 submarine | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5 killed 1 sloop-of-war sunk | none | ||||||

The Sinking of USS Housatonic on 17 February 1864 during the American Civil War was an important turning point in naval warfare. The Confederate States Navy submarine, H.L. Hunley made her first and only attack on a Union Navy warship when she staged a clandestine night attack on the USS Housatonic in Charleston harbor. The Hunley approached just under the surface, avoiding detection until the last moments, then embedded and remotely detonated a spar torpedo that rapidly sank the 1,240 long tons (1,260 t) sloop-of-war with the loss of five Union sailors. The Hunley became renowned as the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy vessel in combat, and was the direct progenitor of what would eventually become international submarine warfare, although the victory was Pyrrhic and short-lived, since the submarine did not survive the attack and was lost with all eight Confederate crewmen.

Sinking

On the evening of 17 February 1864, the Hunley made her first mission against an enemy vessel during the American Civil War. Armed with a spar torpedo, mounted to a rod extending out from her bow, the Hunley's mission was to lift the blockade of Charleston, South Carolina by destroying the sloop-of-war USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor.

Housatonic was a 1,240 long tons (1,260 t) vessel with an armament of twelve large cannons, stationed at the entrance of Charleston Harbor roughly five miles off the coast. Housatonic was commanded by Captain Charles W. Pickering and had a crew of 150 men. The Hunley began her approach at about 8:45 pm, commanded by First Lieutenant George E. Dixon and crewed by seven volunteers.

Accounts differ about the initial approach; what is known is that the Hunley was spotted just before embedding her torpedo into Housatonic's hull. Official accounts say Housatonic was unable to fire a broadside at Hunley, and hit her with only small arms fire. The Hunley attached her explosive to Housatonic's side before reversing and setting a course for home.

A few moments later the torpedo detonated and sank the sloop-of-war. First-hand reports say no explosion was heard by the crew of Housatonic, who immediately began climbing the rigging or entering life boats as the sloop began to sink. Within five minutes, Housatonic was partially underwater. Hunley thus achieved the first sinking of a warship in combat via submarine.

Aftermath

Five men - two officers and three crewmen - went down with their ship while an unknown number of Union Navy sailors were injured. The survivors were later rescued by other elements of the Charleston blockading force. Hunley won her first victory, but was lost at sea the same night while returning home to Sullivan's Island.

It was originally thought that the Hunley was sunk as the result of her own torpedo exploding, but some claim that she survived as long as an hour after destroying the Housatonic. Support for the argument of Hunley's brief survival is a report by the commander of Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island that prearranged signals from the sub were observed, and answered; he did not say what the signal was.[2] Further support comes from the testimony of a lookout on the sunken Housatonic, who reported seeing a "blue light" from his perch in the sunken ship's rigging.[3] There was also a post-war claim that two "blue lights" were the prearranged signal between the sub and Fort Moultrie.[4] "Blue light" at the time of the Civil War was a pyrotechnic signal[5] in long use by the US Navy.[6] Modern claims in published literature on the Hunley have repeatedly and mistakenly been that the "blue light" was a blue lantern, when in fact no blue lantern was found on the recovered Hunley,[7] and period dictionaries and military manuals confirm the 1864 use and meaning of "blue light."[8]

This was the last time the Hunley was heard from, until her recovery from the waters off Charleston, SC. While returning to her naval station Hunley sank for unknown reasons. However, a team of historians managed to examine the submarine's remains, and theorized that a crewman on the Housatonic was able to fire a rifle round into one of the Hunley's viewing ports. A film entitled The Hunley was made about the story of H.L. Hunley and the sinking of the submarine H.L. Hunley.

New evidence announced by archaeologists in 2013 indicates that the Hunley may have been much closer to the point of detonation than previously realized, thus damaging the submarine as well.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "Siege of Charleston Expedition". National Underwater and Marine Agency. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion; Series I – Vol. 15, p. 335.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Naval Court of Inquiry on the Sinking of the Housatonic NARA Publication M 273, Reel 169 Records of the Judge Advocate General (Navy) Record Group 125.

- ↑ Jacob N. Cardozo, Reminiscences of Charleston (Charleston, 1866), p. 124.

- ↑ Noah Webster, International Dictionary of the English Language Comprising the Issues of 1864, 1879 and 1884, ed. Noah Porter, p. 137.

- ↑ George Marshall, Marshall's Practical Marine Gunnery: Containing a View of the Magnitude, Weight, Description and Use of Every Article Used in the Sea Gunner's Department in the Navy of the United States (Norfolk, 1822), pp. 22 and 24.

- ↑ Tom Chaffin, The Hunley The Secret Hope of the Confederacy (New York, 2008), p. 242.

- ↑ The Ordnance Manual for the Use of the Officers of the United States Army 3re ed., 1861, p. 307.

- ↑ Brian Hicks, Hunley legend altered by new discovery, The Post and Courier, 28 January 2013, accessed 28 January 2013.

External links

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- Shipwrecks of the Civil War : Charleston, South Carolina, 1861–1865 map by E. Lee Spence (Sullivan's Island, S.C., 1984) OCLC 11214217

- Robert F. Burgess (1975). Ships Beneath the Sea: A History of Subs and Submersibles. United States of America: McGraw Hill. p. 238.

- http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/h8/housatonic-i.htm

- "Scientists have new clue to mystery of sunken sub". Associated Press. 18 October 2008. http://www.comcast.net/articles/news-science/20081017/Confederate.Submarine/. (Defunct as of 4/2009)

- Trip Atlas, "Events of 1970"

- Cover Story: Time Capsule From The Sea – U.S. News & World Report, 2–9 July 2007

- Official Record of the Union and Confederate Navies during the War of the Rebellion Series I Volume 15 p.328 List of USS Housatonic fatalities