SMS Weissenburg

Painting of Weissenburg in 1902 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Weissenburg |

| Namesake: | Town of Weissenburg |

| Builder: | AG Vulcan Stettin |

| Laid down: | May 1890 |

| Launched: | 14 December 1891 |

| Commissioned: | 14 October 1894 |

| Fate: | Sold to the Ottoman Empire |

| Name: | Turgut Reis |

| Namesake: | Turgut Reis |

| Acquired: | 12 September 1910 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1957 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Brandenburg-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 10,670 t (10,500 long tons) |

| Length: | 115.7 m (379 ft 7 in) |

| Beam: | 19.5 m (64 ft 0 in) |

| Draft: | 7.9 m (25 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power: | 10,000 PS (9,860 ihp; 7,350 kW) |

| Propulsion: | 2-shaft triple expansion engines |

| Speed: | 16.9 knots (31.3 km/h; 19.4 mph) |

| Range: | 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

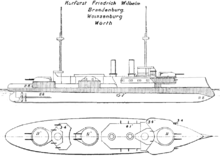

SMS Weissenburg[lower-alpha 1] was one of the first ocean-going battleships[lower-alpha 2] of the Imperial German Navy. She was the third pre-dreadnought of the Brandenburg class, along with her sister ships Brandenburg, Wörth, and Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm. She was laid down in 1890 in the AG Vulcan dockyard in Stettin, launched in 1891, and completed in 1894. The Brandenburg-class battleships were unique for their era in that they carried six large-caliber guns in three twin turrets, as opposed to four guns in two turrets, as was the standard in other navies. The British Royal Navy derisively referred to the ships as "whalers".[1]

Weissenburg saw limited active duty during her service career with the German fleet. She, along with her three sisters, saw one major overseas deployment, to China in 1900–01, during the Boxer Rebellion. The ship underwent a major modernization in 1902–1904. In 1910, Weissenburg was sold to the Ottoman Empire and renamed Turgut Reis, after the famous 16th century Turkish admiral Turgut Reis. The ship saw heavy service during the Balkan Wars, primarily providing artillery support to Ottoman ground forces and taking part in two naval engagements with the Greek navy in December 1912 and January 1913. She was largely inactive during World War I, due in part to her slow speed. In 1924, Turgut Reis was used as a school ship, before eventually being scrapped in the mid-1950s.

Design

Weissenburg was 115.7 m (379 ft 7 in) long overall, had a beam of 19.5 m (64 ft 0 in) which was increased to 19.74 m (64 ft 9 in) with the addition of torpedo nets, and had a draft of 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in) forward and 7.9 m (25 ft 11 in) aft. The ship displaced 10,013 t (9,855 long tons) at its designed weight, and up to 10,670 t (10,500 long tons) at full combat load. She was equipped with two sets of 3-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines that provided 10,228 metric horsepower (10,088 ihp; 7,523 kW) and a top speed of 16.9 knots (31.3 km/h; 19.4 mph); steam was provided by twelve coal-fired, transverse cylindrical water-tube boilers. Weissenburg had a cruising range of 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew numbered 38 officers and 530 enlisted men.[2]

The ship was unusual for its time in that it possessed a broadside of six heavy guns in three twin gun turrets, rather than the four guns typical of contemporary battleships.[1] The forward and after turrets carried 28 cm (11 inch) SK L/40 guns,[lower-alpha 3] while the amidships turret mounted a pair of 28 cm (11 inch) with shorter L/35 barrels. Her secondary armament consisted of eight 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/35 quick-firing guns mounted in casemates and eight 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns, also casemate mounted. Weissenburg's armament system was rounded out with six 45 cm torpedo tubes, all in above-water swivel mounts.[2] Although the main battery was heavier than other capital ships of the period, the secondary armament was considered weak in comparison to other battleships.[1] Weissenburg was protected with nickel-steel Krupp armor, a new type of stronger steel. Her main belt armor was 400 millimeters (15.7 in) thick in the central section that protected the ammunition magazines and machinery spaces. The deck was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick. The main battery barbettes were protected with 300 mm (11.8 in) thick armor.[2]

Service history

Weissenburg was the third of four ships of the Brandenburg class. She was ordered as battleship C, and was laid down at the AG Vulcan shipyard in Stettin in 1890 under construction number 199.[2] She was the third ship of the class to be launched, which she was on 30 June 1891. She was commissioned into the German fleet on 29 April 1894, the same day as her sister Brandenburg.[3] Upon her commissioning, Weissenburg was assigned to the I Division of the I Battle Squadron alongside her three sisters.[4] The I Division was accompanied by the four older Sachsen-class armored frigates in the II Division, though by the time the four Brandenburgs returned from China by 1901–2, the Sachsens were replaced by the new Kaiser Friedrich III-class battleships.[5]

Boxer Rebellion

The first major operation in which Weissenburg took part occurred in 1900, when the I Division was deployed to China to assist in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion.[1] The expeditionary force consisted of the four Brandenburgs, six cruisers, 10 supply ships, three torpedo boats, and six regiments of marines, under the command of Marshal Alfred von Waldersee.[6] Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz opposed the plan, which he saw as unnecessary and costly. Although the naval force arrived in China after the siege of Peking had already been lifted, the task force suppressed local uprisings around Kiaochow. In the end, the operation cost the German government more than 100 million marks.[7]

Service with the Ottoman navy

In 1902, following the return from China, Weissenburg entered the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Wilhelmshaven for a significant reconstruction.[2] After she emerged from her refit in 1904, the ship rejoined the active fleet. However, she and her sisters were rapidly made obsolete by the launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906. As a result, their service careers with the German navy were limited.[1] On 12 September 1910, Weissenburg and Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm, the more advanced ships of the class, were sold to the Ottoman Empire and renamed Turgut Reis and Barbaros Hayreddin, respectively (after the famous 16th-century Ottoman admirals, Turgut Reis and Hayreddin Barbarossa).[8][9][10] A year later, in September 1911, when Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Turgut Reis, along with Barbaros Hayreddin and the obsolete central battery ironclad Mesûdiye had been on a summer training cruise since July, and so were prepared for the conflict. Despite this, the ships spent the war in harbor.[10]

Balkan wars

The Balkan League declared war on the Ottoman Empire in October 1912. In the First Balkan War Turgut Reis, as with most ships of the Ottoman fleet, were in a state of disrepair. During the war, Turgut Reis conducted gunnery training along with the other capital ships of the Ottoman navy, escorted troop convoys, and bombarded coastal installations.[9] On 17 November 1912, Turgut Reis supported the Ottoman III Corps by bombarding the attacking Bulgarian forces. The ship was aided by artillery observers ashore.[11] The battleship's gunnery was largely ineffective, though it provided a morale boost for the besieged Ottoman army dug in at Çatalca. By 17:00, the Bulgarian infantry had largely been forced back to their starting positions, in part due to the psychological effect of the battleships' bombardment.[12]

Late in 1912, the Ottoman fleet attacked the Greek navy, in an attempt to disrupt the naval blockade surrounding the Dardanelles. Two engagements took place, the Naval Battle of Elli on 16 December 1912, followed by the Naval Battle of Lemnos on 18 January 1913. The first action was supported by Ottoman coastal batteries; both Greek and Ottoman forces suffered minor damage during the engagement, but the Ottomans were unable to break through the Greek fleet and retired back into the Dardanelles.[13] The Ottoman fleet, which included Turgut Reis, her sister Barbaros Hayreddin—the flagship of the fleet—two outdated ironclad battleships, nine destroyers and six torpedo boats, sortied from the Dardanelles at 9:30. The smaller ships remained at the mouth of the straits while the battleships sailed north, while remaining near to the coast. The Greek flotilla, which included the armored cruiser Georgios Averof and three Hydra-class battleships, had been sailing from the island of Imbros to the patrol line outside the straits. When the Ottomans were sighted, the Greeks altered course to the northeast, in order to block the advance of their opponents. The Ottoman ships opened fire first, at 9:50, from a range of about 15,000 yards; the Greeks returned fire ten minutes later, by which time the range had decreased significantly to 8,500 yards. At 10:04, the Ottoman ships completed a 16-point turn, which reversed their course, and steamed for the safety of the straits in a disorganized withdrawal.[14] Within an hour, the routed Ottoman ships had withdrawn into the Dardanelles.[13]

The Naval Battle of Lemnos resulted from an Ottoman plan to lure the faster Georgios Averof away from the Dardanelles. The protected cruiser Hamidiye evaded the Greek blockade and broke out into the Aegean Sea; the assumption was that the Greeks would dispatch Georgios Averof to hunt down Hamidiye. Despite the threat to Greek lines of communication posed by the cruiser, the Greek commander refused to detach Georgios Averof from its position. However, presuming that the plan had worked, Turgut Reis, Barbaros Hayreddin, and other units of the Ottoman fleet departed the Dardanelles on the morning of 18 January, and sailed towards the island of Lemnos. Georgios Averof appeared approximately 12 miles from Lemnos; when the powerful Greek ship was spotted, the Ottomans turned to retreat. Georgios Averof's superior speed allowed the ship to close the distance between her and the fleeing Ottoman ships. A long range artillery duel that lasted for two hours began at around 11:25; towards the end of the engagement, Georgios Averof closed to within 5,000 yards and scored several hits on the fleeing Ottoman ships.[14] Between Turgut Reis and Barbaros Hayreddin, the ships fired some 800 rounds, mostly of their main battery 28 cm guns but without success. During the battle, barbettes on both Turgut Reis and her sister were disabled by gunfire, and both ships caught fire.[15]

On 8 February 1913, the Ottoman navy supported an amphibious assault at Şarköy. Turgut Reis and Barbaros Hayreddin, along with two small cruisers provided artillery support to the right flank of the invading force once it went ashore. The ships were positioned about a kilometer off shore; Turgut Reis was the second ship in the line, behind her sister Barbaros Hayreddin.[16] The Bulgarian army resisted fiercely, which ultimately forced the Ottoman army to retreat, though the withdrawal was successful in large part due to the gunfire support from Turgut Reis and the rest of the fleet. During the battle, Turgut Reis fired 225 rounds from her 10.5 cm guns and 202 shells from her 8.8 cm guns.[17]

In March 1913, the ship returned to the Black Sea to resume support of the Çatalca garrison, which was under renewed attacks by the Bulgarian army. On 26 March, the barrage of 28 and 10.5 cm shells fired by Turgut Reis and Barbaros Hayreddin assisted in the repelling of advance of the 2nd Brigade of the Bulgarian 1st Infantry Division.[18] On 30 March, the left wing of the Ottoman line turned to pursue the retreating Bulgarians. Their advance was supported by both field artillery and the heavy guns of Turgut Reis and the other warships positioned off the coast; the assault gained the Ottomans about 1,500 meters by nightfall. In response, the Bulgarians brought the 1st Brigade to the front, which beat the Ottoman advance back to its starting position.[19]

World War I

In the summer of 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, the Ottomans initially remained neutral. In early November, the actions of the German battlecruiser SMS Goeben, which had been transferred to the Ottoman navy and renamed Yavûz Sultân Selîm, resulted in declarations of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain.[20] Between 1914–15, some of Turgut Reis's guns were removed and employed as coastal guns to shore up the defenses protecting the Dardanelles.[15] On 19 January 1918, Yavûz and the light cruiser SMS Breslau, which had also been transferred to Ottoman service under the name Midilli, sailed from the Dardanelles to attack several British monitors stationed outside. The ships quickly sank HMS Raglan and HMS M28 before turning back to the safety of the Dardanelles. While en route, Midilli struck five mines and sank, while Yavûz hit three mines and began to list to port. The ship's captain gave an incorrect order to the helmsman, which caused the ship to run aground. Yavûz remained there for almost a week, until Turgut Reis arrived on the scene on 25 January; the old battleship took Yavûz under tow and managed to free her from the sandbank by that afternoon.[21]

Turgut Reis was removed from active service after the end of World War I. By 1924, the ship was transferred to the role of a training ship.[8] At the time, she retained only two of her originally six 28 cm guns.[15] Turgut Reis was converted into a hulk and stationed in the Dardanelles until 1938.[8] She remained afloat until she was finally broken up for scrap, between 1956–57.[15]

Notes

- ↑ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

- ↑ At the time, the German navy referred to the ship as a "ship of the line" (Linienschiff in German), instead of "battleship" (Schlachtschiff).

- ↑ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 caliber, meaning that the gun barrel is 40 times as long as it is in diameter.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hore, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gröner, p. 13.

- ↑ Gardiner Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 247.

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray, p. 141.

- ↑ Herwig, p. 45.

- ↑ Herwig, p. 106.

- ↑ Herwig, p. 103.

- 1 2 3 Gröner, p. 14.

- 1 2 Erickson, p. 131.

- 1 2 Sondhaus, p. 218.

- ↑ Hall, p. 36.

- ↑ Erickson, p. 133.

- 1 2 Hall, pp. 64–65.

- 1 2 Fotakis, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Gardiner & Gray, p. 390.

- ↑ Erickson, p. 264.

- ↑ Erickson, p. 270.

- ↑ Erickson, p. 288.

- ↑ Erickson, p. 289.

- ↑ Staff, p. 19.

- ↑ Bennett, p. 47.

References

- Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. London: Pen & Sword Military Classics. ISBN 978-1-84415-300-8.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4.

- Fotakis, Zisis (2005). Greek Naval Strategy and Policy, 1910–1919. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35014-3.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22946-3.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3.