Tyrian purple

| Tyrian purple | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #66023C |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (102, 2, 60) |

| CMYKH (c, m, y, k) | (45, 100, 47, 42) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (325°, 98%, 40[1]%) |

| Source | Tyrian purple |

|

B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Tyrian purple (Greek, πορφύρα, porphyra, Latin: purpura), also known as Tyrian red, royal purple, imperial purple or imperial dye, is a bromine-containing reddish-purple natural dye. It is a secretion produced by several species of predatory sea snails in the family Muricidae, rock snails originally known by the name Murex.

Background

Tyrian purple may first have been used by the ancient Phoenicians as early as 1570 BC.[2] The dye was greatly prized in antiquity because the colour did not easily fade, but instead became brighter with weathering and sunlight. Its significance is such that the name Phoenicia means 'land of purple.'[3][4] It came in various shades, the most prized being that of "blackish clotted blood".[5]

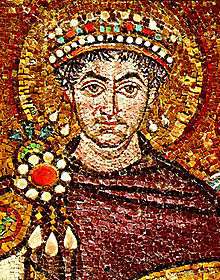

Tyrian purple was expensive: the 4th-century-BC historian Theopompus reported, "Purple for dyes fetched its weight in silver at Colophon" in Asia Minor.[6] The expense meant that purple-dyed textiles became status symbols, and early sumptuary laws restricted their uses. The production of Tyrian purple was tightly controlled in Byzantium and was subsidized by the imperial court, which restricted its use for the colouring of imperial silks.[7] Later (9th century)[8] a child born to a reigning emperor was said to be porphyrogenitos, "born in the purple".

This is speculation, and a matter of debate today, but according to some, in Biblical Hebrew, the dye extracted from the Bolinus brandaris is known as argaman (ארגמן). Another dye extracted from a related sea snail, Hexaplex trunculus, produced a blue colour which according to some is known as tekhelet (תְּכֵלֶת), used in garments worn for ritual purposes.[9]

Production from sea snails

The dye substance is a mucous secretion from the hypobranchial gland of one of several species of medium-sized predatory sea snails that are found in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. These are the marine gastropods Bolinus brandaris the spiny dyemurex, (originally known as Murex brandaris (Linnaeus, 1758)), the banded dye-murex Hexaplex trunculus, the rock-shell Stramonita haemastoma,[10][11] and less commonly a number of other species such as Bolinus cornutus. The dye is an organic compound of bromine (i.e., an organobromine compound), a class of compounds often found in algae and in some other sea life, but much more rarely found in the biology of land animals.

In nature the snails use the secretion as part of their predatory behaviour in order to sedate prey and as an antimicrobial lining on egg masses.[12][13] The snail also secretes this substance when it is attacked by predators, or physically antagonized by humans (e.g., poked). Therefore, the dye can be collected either by "milking" the snails, which is more labour-intensive but is a renewable resource, or by collecting and destructively crushing the snails. David Jacoby remarks that "twelve thousand snails of Murex brandaris yield no more than 1.4 g of pure dye, enough to colour only the trim of a single garment."[14]

Many other species worldwide within the family Muricidae, for example Plicopurpura pansa,[15] from the tropical eastern Pacific, and Plicopurpura patula[16] from the Caribbean zone of the western Atlantic, can also produce a similar substance (which turns into an enduring purple dye when exposed to sunlight) and this ability has sometimes also been historically exploited by local inhabitants in the areas where these snails occur. (Some other predatory gastropods, such as some wentletraps in the family Epitoniidae, seem to also produce a similar substance, although this has not been studied or exploited commercially.) The dog whelk Nucella lapillus, from the North Atlantic, can also be used to produce red-purple and violet dyes.[17]

Royal blue

The Phoenicians also made an indigo dye, sometimes referred to as royal blue or hyacinth purple, which was made from a closely related species of marine snail.[18]

The Phoenicians established an ancillary production facility on the Iles Purpuraires at Mogador, in Morocco.[19] The sea snail harvested at this western Moroccan dye production facility was Hexaplex trunculus (mentioned above) also known by the older name Murex trunculus.[20]

This second species of dye murex is found today on the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa (Spain and Portugal, Morocco, and the Canary Islands).[11]

History

The colour-fast (non-fading) dye was an item of luxury trade, prized by Romans, who used it to colour ceremonial robes. Used as a dye, the colour shifts from blue (peak absorption at 590 nm, which is yellow-orange) to reddish-purple (peak absorption at 520 nm, which is green).[21] It is believed that the intensity of the purple hue improved rather than faded as the dyed cloth aged. Vitruvius mentions the production of Tyrian purple from shellfish.[22] In his History of Animals, Aristotle described the shellfish from which Tyrian purple was obtained and the process of extracting the tissue that produced the dye.[23] Pliny the Elder described the production of Tyrian purple in his Natural History:[24][25]

The most favourable season for taking these [shellfish] is after the rising of the Dog-star, or else before spring; for when they have once discharged their waxy secretion, their juices have no consistency: this, however, is a fact unknown in the dyers' workshops, although it is a point of primary importance. After it is taken, the vein [i.e. hypobranchial gland] is extracted, which we have previously spoken of, to which it is requisite to add salt, a sextarius [about 20 fl. oz.] about to every hundred pounds of juice. It is sufficient to leave them to steep for a period of three days, and no more, for the fresher they are, the greater virtue there is in the liquor. It is then set to boil in vessels of tin [or lead], and every hundred amphoræ ought to be boiled down to five hundred pounds of dye, by the application of a moderate heat; for which purpose the vessel is placed at the end of a long funnel, which communicates with the furnace; while thus boiling, the liquor is skimmed from time to time, and with it the flesh, which necessarily adheres to the veins. About the tenth day, generally, the whole contents of the cauldron are in a liquefied state, upon which a fleece, from which the grease has been cleansed, is plunged into it by way of making trial; but until such time as the colour is found to satisfy the wishes of those preparing it, the liquor is still kept on the boil. The tint that inclines to red is looked upon as inferior to that which is of a blackish hue. The wool is left to lie in soak for five hours, and then, after carding it, it is thrown in again, until it has fully imbibed the colour.

Archaeological data from Tyre indicate that the snails were collected in large vats and left to decompose. This produced a hideous stench that was actually mentioned by ancient authors. Not much is known about the subsequent steps, and the actual ancient method for mass-producing the two murex dyes has not yet been successfully reconstructed; this special "blackish clotted blood" colour, which was prized above all others, is believed to be achieved by double-dipping the cloth, once in the indigo dye of H. trunculus and once in the purple-red dye of B. brandaris.[5][18]

The Roman mythographer Julius Pollux, writing in the 2nd century AD, asserted (Onomasticon I, 45–49) that the purple dye was first discovered by Heracles, or rather, by his dog, whose mouth was stained purple from chewing on snails along the coast of the Levant. Recently, the archaeological discovery of substantial numbers of Murex shells on Crete suggests that the Minoans may have pioneered the extraction of Imperial purple centuries before the Tyrians. Dating from collocated pottery suggests the dye may have been produced during the Middle Minoan period in the 20th–18th century BC.[26] Accumulations of crushed murex shells from a hut at the site of Coppa Nevigata in southern Italy may indicate production of purple dye there from at least the 18th century BC.[27]

The production of Murex purple for the Byzantine court came to an abrupt end with the sack of Constantinople in 1204, the critical episode of the Fourth Crusade. David Jacoby concludes that "no Byzantine emperor nor any Latin ruler in former Byzantine territories could muster the financial resources required for the pursuit of murex purple production. On the other hand, murex fishing and dyeing with genuine purple are attested for Egypt in the tenth to 13th centuries."[28] By contrast, Jacoby finds that there are no mentions of purple fishing or dyeing, nor trade in the colorant in any Western source, even in the Frankish Levant. The European West turned instead to vermilion provided by the insect Kermes vermilio, known as grana, or crimson.

In 1909, Harvard anthropologist Zelia Nuttall compiled an intensive comparative study on the historical production of the purple dye produced from the carnivorous murex snail, source of the royal purple dye valued higher than gold in the ancient Near East and ancient Mexico. Not only did the people of ancient Mexico use the same methods of production as the Phoenicians, they also valued murex-dyed cloth above all others, as it appeared in codices as the attire of nobility. "Nuttall noted that the Mexican murex-dyed cloth bore a "disagreeable... strong fishy smell, which appears to be as lasting as the color itself.[29] Likewise, the ancient Egyptian Papyrus of Anastasi laments: "The hands of the dyer reek like rotting fish..."[30] So pervasive was this stench that the Talmud specifically granted women the right to divorce any husband who became a dyer after marrying".[31]

Murex purple production in Tunisia

Murex purple was a very important industry in many Phoenician colonies and Carthage was no exception. Traces of this once very lucrative industry are still visible in many Punic sites such as Kerkouane, Zouchis, Meninx and even in Carthage itself. According to Pliny, Meninx (today's Djerba) produced the best purple in Africa which was also ranked second only after Tyre's.

Dye chemistry

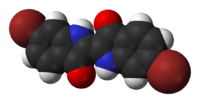

The main chemical constituent of the Tyrian dye was discovered by Paul Friedländer in 1909 to be 6,6′-dibromoindigo, a substance that had previously been synthesized in 1903. The dye was thus shown to be an organobromine compound.[32][33] However, it has never been synthesized commercially.[34][35]

In 1998, through a lengthy trial and error process, an English engineer named John Edmonds rediscovered a process for dyeing with Tyrian purple.[36][37] He researched recipes and observations of dyers from the 15th century to the 18th century. He explored the biotechnology process behind woad fermentation. After collaborating with a chemist, Edmonds hypothesized that an alkaline fermenting vat was necessary. He studied an incomplete ancient recipe for Tyrian purple recorded by Pliny the Elder. By altering the percentage of sea salt in the dye vat and adding potash, he was able to successfully dye wool a deep purple colour.[38]

Recent research in organic electronics has shown that Tyrian purple is an ambipolar organic semiconductor. Transistors and circuits based on this material can be produced from sublimed thin-films of the dye. The good semiconducting properties of the dye originate from strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding that reinforces pi stacking necessary for transport.[39]

Modern hue rendering

Tyrian purple

Azalea Society of America hue rendering

True Tyrian purple, like most high-chroma pigments, cannot be accurately displayed on a computer display. Ancient reports are also not entirely consistent, but these swatches give an indication of the likely range in which it appeared:

_________

_________

This is the sRGB colour #990024, intended for viewing on an output device with a gamma of 2.2. It is a representation of RHS colour code 66A,[40] which has been equated to "Tyrian red",[41] a term which is often used as a synonym for Tyrian purple.

Philately

The colour name "Tyrian plum" is popularly given to a British postage stamp that was prepared, but never released to the public, shortly before the death of King Edward VII in 1910.

-

Painting of a man wearing an all-purple toga picta, from an Etruscan tomb (about 350 BC).

-

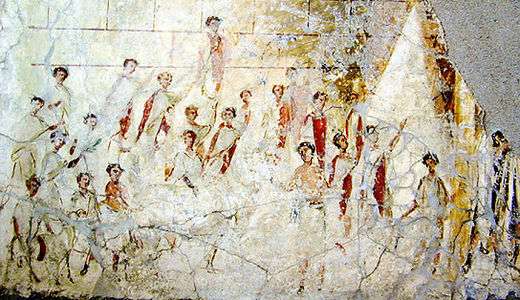

Roman men wearing togae praetextae with reddish-purple stripes during a religious procession (1st century BC).

-

The Empress Theodora, the wife of the Emperor Justinian, dressed in Tyrian purple. (6th century).

-

A medieval depiction of the coronation of the Emperor Charlemagne in 800. The bishops and cardinals wear Tyrian purple, and the Pope wears white.

-

A fragment of the shroud in which the Emperor Charlemagne was buried in 814. It was made of gold and Tyrian purple from Constantinople.

-

Heracles and the Discovery of the Secret of Purple by Peter Paul Rubens (1636), Musée Bonnat

-

6,6'-dibromoindigo, the major component of Tyrian purple

See also

References

- ↑ web.Forret.com Color Conversion Tool set to colour #66023C (Tyrian purple):

- ↑ McGovern, P. E. and Michel, R. H.; Royal Purple dye: tracing the chemical origins of the industry, Anal. Chem. 1985, 57, 1514A-1522A

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry. Europe Between the Oceans; 9000 BC-AD 1000. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 241.

- ↑ "Phoenician". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- 1 2 "Pigments | Causes of Color". www.webexhibits.org. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ↑ Theopompus, cited by Athenaeus (12:526) around 200 BC; according to Gulick, Charles Barton 1941. Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ David Jacoby, "Silk in Western Byzantium before the Fourth Crusade" in Trade, Commodities, and Shipping in the Medieval Mediterranean (1997) pp. 455f and notes 17–19.

- ↑ Porphyrogennetos" in The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 1701. ISBN 0-195-04652-8

- ↑ O. Elsner, "Solution of the enigmas of dyeing with Tyrian purple and the Biblical tekhelet", Dyes in history and Archaeology 10 (1992) p 14f.

- ↑ Ziderman, I.I., 1986. Purple dye made from shellfish in antiquity. Review of Progress in Coloration, 16: 46–52.

- 1 2 Radwin, G. E. and A. D'Attilio, 1986. Murex shells of the world. An illustrated guide to the Muricidae, p93, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, USA, 284pp incl 192 figs. & 32 pls.

- ↑ Benkendorff, Kirsten (March 1999). "Bioactive molluscan resources and their conservation: Biological and chemical studies on the egg masses of marine molluscs". University of Wollongong. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-30. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Because of research by Benkendorff et al., the Tyrian purple precursor tyrindoleninone is being investigated as a potential antimicrobial agent with uses against multidrug resistant bacteria.

- ↑ Jacoby, "Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West" Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58 (2004:197–240) p. 210.

- ↑ Gould, 1853

- ↑ Linnaeus, 1758a

- ↑ Whelks and purple dye in Anglo-Saxon England. Carole P. Biggam. Department of English Language, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK THE ARCHAEO+MALACOLOGY GROUP NEWSLETTER. Issue Number 9, March 2006.

- 1 2 Moorey, Peter (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 138. ISBN 1-57506-042-6.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, Mogador: Promontory Fort, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham, November 2, 2007

- ↑ Linnaeus, 1758b

- ↑ Christopher J. Cooksey, “Tyrian Purple: 6,6’-Dibromoindigo and Related Compounds,” Molecules, 2001, 6: 736–769.

- ↑ Vitruvius, De Architectura, Book VII, Chapter 13.

- ↑ Aristotle, History of Animals (Whitefish, Montana, U.S.: Kessering Publishing, 2004), Book V, see especially pages 131–132.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, eds. John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley (London, England: Taylor and Francis, 1855), Book IX. The Natural History of Fishes. Chapter 62. Pliny discusses Tyrian purple in Chapters 60–65 of his Natural History.

- ↑ The problem with Tyrian purple is that the precursor reacts very quickly with air and light to form an insoluble dye. (Hence Pliny says: "...when [the shellfish] have once discharged their waxy secretion, their juices have no consistency....") The cumbersome process that Pliny describes is necessary to reverse the oxidation and to restore the water-soluble precursor so that large masses of wool can be dyed. See: Carole P. Biggam (2006) "Knowledge of whelk dyes and pigments in Anglo-Saxon England," Anglo-Saxon England, vol. 35, pages 23–56; see especially pages 26–27. See also: C. J. Cooksey (2001) "Tyrian purple: 6,6’-Dibromoindigo and Related Compounds," Molecules, vol. 6, no. 9, pages 736–769, especially page 761. Indigo, which is chemically very similar to Tyrian purple, behaves similarly. See: http://www.indigopage.com/chemistry.htm

- ↑ Reese, David S. (1987). "Palaikastro Shells and Bronze Age Purple-Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin," Annual of the British School of Archaeology at Athens, 82, 201–6); Stieglitz, Robert R. (1994), "The Minoan Origin of Tyrian Purple," Biblical Archaeologist, 57, 46–54.

- ↑ Cazzella, Alberto & Maurizio Moscoloni. 1998. "Coppa Nevigata: un insediamento fortificato dell'eta del Bronzo," in Luciana Drago Troccoli (ed.), Scavi e ricerche archeologiche dell'Università di Roma La Sapienza, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Jacoby 2004, p. 210.

- ↑ Nuttall, Zelia (April 16, 1909). "A Curious Survival in Mexico of the Use of the Purpura Shell-fish for Dyeing". Putnam Anniversary Volume. Anthropological Essays Presented to Fredrick Ward Putnam in Honor of his Seventieth Birthday, by his Friends and Associates, ed. F. Boas (New York: G. E. Strechert & Co., Publishers, 1909): 368–384. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Robinson, Stuart (1969). A History of Dyed Textiles. London: Sudio Vista. p. 24.

- ↑ Compton, Stephen (2010). Exodus Lost (first ed.). Booksurge Publishing. pp. 29–33. ISBN 9781439276839.

- ↑ Friedlaender, P. (1909). "Zur Kenntnis des Farbstoffes des antiken Purpurs aus Murex brandaris" ([Contribution] to our knowledge of the ancient purple dye from Murex brandaris). Monatshefte für Chemie … , 30: 247–253.

- ↑ Sachs, F. & Kempf, R. (1903). "Über p-Halogen-o-nitrobenzaldehyde". Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 36 (3): 3299–3303. doi:10.1002/cber.190303603113.

- ↑ "Indigo". Encyclopædia Britannica. V (15th ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1981. p. 338. ISBN 0-85229-378-X.

- ↑ Cooksey C. J. (2001). "Tyrian purple: 6,6'-Dibromoindigo and Related Compounds" (PDF). Molecules. 6 (9): 736–769. doi:10.3390/60900736.

- ↑ John Edmonds, Tyrian or Imperial Purple: The Mystery of Imperial Purple Dyes, Historic Dye Series, no. 7 (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England: John Edwards, 2000).

- ↑ Article about John Edmonds: http://www.imperial-purple.com/profile.html

- ↑ Chenciner, Robert. Madder red: a history of luxury and trade: plant dyes and pigments in world commerce and art. Richmond: Curzon Press, 2000. P.295

- ↑ Ambipolar organic field effect transistors and inverters with the natural material Tyrian Purple, E. D. Głowacki et al., AIP Advances 1, 042132 (2011)

- ↑ "RHS, UCL and RGB Colors, gamma = 1.4, fan 2", Azalea Society of America website (this gives the RGB value #b80049, which has been converted to #990024 for the sRGB gamma of 2.2)

- ↑ Buck, G. Buck Rose Website, Page 5

External links

- Tyrian Purple - Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Bibliography from Chris J. Cooksey (1994) "Making Tyrian purple," Dyes in History and Archaeology, vol. 13, pages 7–13.

- The Free Library: article on Tyrian purple

- Royal Purple of Tyre