Presidencies of Grover Cleveland

The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland lasted from March 4, 1885 to March 4, 1889, and from March 4, 1893 to March 4, 1897. The first Democrat elected after the Civil War, Grover Cleveland is the only United States President to leave office after one term and later return for a second term. His presidencies were the nation's 22nd and 24th.[lower-alpha 1] Cleveland defeated James G. Blaine of Maine in 1884, lost to Benjamin Harrison of Indiana in 1888, and then defeated President Harrison in 1892.

Cleveland was the leader of the pro-business Bourbon Democrats who opposed high tariffs, Free Silver, inflation, imperialism, and subsidies to business, farmers, or veterans. His crusade for political reform and fiscal conservatism made him an icon for American conservatives of the era.[1] Cleveland won praise for his honesty, self-reliance, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism.[2] He relentlessly fought political corruption, patronage, and bossism. As a reformer Cleveland had such prestige that the like-minded wing of the Republican Party, called "Mugwumps", largely bolted the GOP presidential ticket and swung to his support in the 1884 election.[3]

As his second presidency began, disaster hit the nation when the Panic of 1893 produced a severe national depression, which Cleveland was unable to reverse. It ruined his Democratic Party, opening the way for a Republican landslide in 1894 and for the agrarian and silverite seizure of the Democratic Party in 1896. The result was a political realignment that ended the Third Party System and launched the Fourth Party System and the Progressive Era.[4]

Cleveland was a formidable policymaker, and he also drew corresponding criticism. His intervention in the Pullman Strike of 1894 to keep the railroads moving angered labor unions nationwide in addition to the party in Illinois; his support of the gold standard and opposition to Free Silver alienated the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party.[5] Critics complained that Cleveland had little imagination and seemed overwhelmed by the nation's economic disasters—depressions and strikes—in his second term.[5] Even so, his reputation for probity and good character survived the troubles of his second term. Biographer Allan Nevins wrote: "[I]n Grover Cleveland the greatness lies in typical rather than unusual qualities. He had no endowments that thousands of men do not have. He possessed honesty, courage, firmness, independence, and common sense. But he possessed them to a degree other men do not.[6]"

Cleveland, a bachelor when he became President in 1885, married Frances Folsom in the Blue Room at the White House on June 2, 1886; he is the only President married in the White House. After leaving office, Cleveland lived in retirement in Princeton, New Jersey. He died on June 24, 1908, and is buried in Princeton Cemetery. Today, Cleveland is considered by most historians to have been a successful leader, generally ranked among the second tier of American presidents.

First presidency (1885–1889)

Reform

Soon after taking office, Cleveland was faced with the task of filling all the government jobs for which the president had the power of appointment. These jobs were typically filled under the spoils system, but Cleveland announced that he would not fire any Republican who was doing his job well, and would not appoint anyone solely on the basis of party service.[7] He also used his appointment powers to reduce the number of federal employees, as many departments had become bloated with political time-servers.[8] Later in his term, as his fellow Democrats chafed at being excluded from the spoils, Cleveland began to replace more of the partisan Republican officeholders with Democrats.;[9] this was especially the case with policy making positions.[10] While some of his decisions were influenced by party concerns, more of Cleveland's appointments were decided by merit alone than was the case in his predecessors' administrations.[11]

BEP engraved portrait of Cleveland as President.

Cleveland also reformed other parts of the government. In 1887, he signed an act creating the Interstate Commerce Commission.[12] He and Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney undertook to modernize the navy and canceled construction contracts that had resulted in inferior ships.[13] Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of western lands they held by government grant.[14] Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q.C. Lamar charged that the rights of way for this land must be returned to the public because the railroads failed to extend their lines according to agreements.[14] The lands were forfeited, resulting in the return of approximately 81,000,000 acres (330,000 km2).[14]

Cleveland was the first Democratic President subject to the Tenure of Office Act which originated in 1867; the act purported to require the Senate to approve the dismissal of any presidential appointee who was originally subject to its advice and consent. Cleveland objected to the act in principle and his steadfast refusal to abide by it prompted its fall into disfavor and led to its ultimate repeal in 1887.[15]

Vetoes

Cleveland faced a Republican Senate and often resorted to using his veto powers.[16] He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for American Civil War veterans, believing that if their pensions requests had already been rejected by the Pension Bureau, Congress should not attempt to override that decision.[17] When Congress, pressured by the Grand Army of the Republic, passed a bill granting pensions for disabilities not caused by military service, Cleveland also vetoed that.[18] Cleveland used the veto far more often than any president up to that time.[19] In 1887, Cleveland issued his most well-known veto, that of the Texas Seed Bill.[20] After a drought had ruined crops in several Texas counties, Congress appropriated $10,000 to purchase seed grain for farmers there.[20] Cleveland vetoed the expenditure. In his veto message, he espoused a theory of limited government:

I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution, and I do not believe that the power and duty of the general government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadfastly resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that, though the people support the government, the government should not support the people. The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow-citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.[21]

Silver

One of the most volatile issues of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone.[22] The issue cut across party lines, with western Republicans and southern Democrats joining together in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the northeast holding firm for the gold standard.[23] Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply.[23]

Cleveland and Treasury Secretary Daniel Manning stood firmly on the side of the gold standard, and tried to reduce the amount of silver that the government was required to coin under the Bland-Allison Act of 1878.[24] Cleveland unsuccessfully appealed to Congress to repeal this law before he was inaugurated.[25] Angered Westerners and Southerners advocated for cheap money to help their poorer constituents.[26] In reply, one of the foremost silverites, Richard P. Bland, introduced a bill in 1886 that would require the government to coin unlimited amounts of silver, inflating the then-deflating currency.[27] While Bland's bill was defeated, so was a bill the administration favored that would repeal any silver coinage requirement.[27] The result was a retention of the status quo, and a postponement of the resolution of the Free Silver issue.[28]

Tariffs

| "When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, it is plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice ... The public Treasury, which should only exist as a conduit conveying the people's tribute to its legitimate objects of expenditure, becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people's use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country's development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder." |

| Cleveland's third annual message to Congress, December 6, 1887.[29] |

Another contentious financial issue at the time was the protective tariff. While it had not been a central point in his campaign, Cleveland's opinion on the tariff was that of most Democrats: that the tariff ought to be reduced.[30] Republicans generally favored a high tariff to protect American industries.[30] American tariffs had been high since the Civil War, and by the 1880s the tariff brought in so much revenue that the government was running a surplus.[31]

In 1886, a bill to reduce the tariff was narrowly defeated in the House.[32] The tariff issue was emphasized in the Congressional elections that year, and the forces of protectionism increased their numbers in the Congress, but Cleveland continued to advocate tariff reform.[33] As the surplus grew, Cleveland and the reformers called for a tariff for revenue only.[34] His message to Congress in 1887 (quoted at right) highlighted the injustice of taking more money from the people than the government needed to pay its operating expenses.[35] Republicans, as well as protectionist northern Democrats like Samuel J. Randall, believed that American industries would fail absent high tariffs, and continued to fight reform efforts.[36] Roger Q. Mills, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, proposed a bill to reduce the tariff from about 47% to about 40%.[37] After significant exertions by Cleveland and his allies, the bill passed the House.[37] The Republican Senate failed to come to agreement with the Democratic House, and the bill died in the conference committee. Dispute over the tariff persisted into the 1888 presidential election.

Foreign policy, 1885–1889

Cleveland was a committed non-interventionist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He refused to promote the previous administration's Nicaragua canal treaty, and generally was less of an expansionist in foreign relations.[38] Cleveland's Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard, negotiated with Joseph Chamberlain of the United Kingdom over fishing rights in the waters off Canada, and struck a conciliatory note, despite the opposition of New England's Republican Senators.[39] Cleveland also withdrew from Senate consideration the Berlin Conference treaty which guaranteed an open door for U.S. interests in the Congo.[40]

Military policy, 1885–1889

Cleveland's military policy emphasized self-defense and modernization. In 1885 Cleveland appointed the Board of Fortifications under Secretary of War William C. Endicott to recommend a new coastal fortification system for the United States.[41][42] No improvements to US coastal defenses had been made since the late 1870s.[43][44] The Board's 1886 report recommended a massive $127 million construction program at 29 harbors and river estuaries, to include new breech-loading rifled guns, mortars, and naval minefields. The Board and the program are usually called the Endicott Board and the Endicott Program. Most of the Board's recommendations were implemented, and by 1910 27 locations were defended by over 70 forts.[45][46] Many of the weapons remained in place until scrapped in World War II as they were replaced with new defenses. Endicott also proposed to Congress a system of examinations for Army officer promotions.[47] For the Navy, the Cleveland administration spearheaded by Secretary of the Navy William Collins Whitney moved towards modernization, although no ships were constructed that could match the best European warships. Although completion of the four steel-hulled warships begun under the previous administration was delayed due to a corruption investigation and subsequent bankruptcy of their building yard, these ships were completed in a timely manner in naval shipyards once the investigation was over.[48] Sixteen additional steel-hulled warships were ordered by the end of 1888; these ships later proved vital in the Spanish–American War of 1898, and many served in World War I. These ships included the "second-class battleships" Maine and Texas, designed to match modern armored ships recently acquired by South American countries from Europe, such as the Brazilian battleship Riachuelo.[49] Eleven protected cruisers (including the famous Olympia), one armored cruiser, and one monitor were also ordered, along with the experimental cruiser Vesuvius.[50]

Civil rights and immigration

Cleveland, like a growing number of Northerners (and nearly all white Southerners) saw Reconstruction as a failed experiment, and was reluctant to use federal power to enforce the 15th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed voting rights to African Americans.[51] Though Cleveland appointed no black Americans to patronage jobs, he allowed Frederick Douglass to continue in his post as recorder of deeds in Washington, D.C. and appointed another black man to replace Douglass upon his resignation.[51]

Although Cleveland had condemned the "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, he believed that Chinese immigrants were unwilling to assimilate into white society.[52] Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard negotiated an extension to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Cleveland lobbied the Congress to pass the Scott Act, written by Congressman William Lawrence Scott, which prevented the return of Chinese immigrants who left the United States.[53] The Scott Act easily passed both houses of Congress, and Cleveland signed it into law on October 1, 1888.[53]

Indian policy

Cleveland viewed Native Americans as wards of the state, saying in his first inaugural address that "[t]his guardianship involves, on our part, efforts for the improvement of their condition and enforcement of their rights."[54] He encouraged the idea of cultural assimilation, pushing for the passage of the Dawes Act, which provided for distribution of Indian lands to individual members of tribes, rather than having them continued to be held in trust for the tribes by the federal government.[54] While a conference of Native leaders endorsed the act, in practice the majority of Native Americans disapproved of it.[55] Cleveland believed the Dawes Act would lift Native Americans out of poverty and encourage their assimilation into white society. It ultimately weakened the tribal governments and allowed individual Indians to sell land and keep the money.[54]

In the month before Cleveland's 1885 inauguration, President Arthur opened four million acres of Winnebago and Crow Creek Indian lands in the Dakota Territory to white settlement by executive order.[56] Tens of thousands of settlers gathered at the border of these lands and prepared to take possession of them.[56] Cleveland believed Arthur's order to be in violation of treaties with the tribes, and rescinded it on April 17 of that year, ordering the settlers out of the territory.[56] Cleveland sent in eighteen companies of Army troops to enforce the treaties and ordered General Philip Sheridan, at the time Commanding General of the U. S. Army, to investigate the matter.[56]

Marriage and children

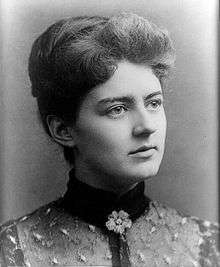

Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor, and his sister Rose Cleveland joined him, to act as hostess for the first two years of his administration.[57] However, unlike the previous bachelor president James Buchanan, Cleveland did not remain a bachelor for very long. In 1885 the daughter of Cleveland's friend Oscar Folsom visited him in Washington.[58] Frances Folsom was a student at Wells College. When she returned to school, President Cleveland received her mother's permission to correspond with her, and they were soon engaged to be married.[58] On June 2, 1886, Cleveland married Frances Folsom in the Blue Room at the White House.[59] He was the second President to wed while in office,[60] and has been the only President married in the White House. This marriage was unusual, since Cleveland was the executor of Oscar Folsom's estate and had supervised Frances's upbringing after her father's death; nevertheless, the public took no exception to the match.[61] At 21 years, Frances Folsom Cleveland was the youngest First Lady in history, and the public soon warmed to her beauty and warm personality.[62]

The Clevelands had five children: Ruth (1891–1904), Esther (1893–1980), Marion (1895–1977), Richard Folsom (1897–1974), and Francis Grover (1903–1995). British philosopher Philippa Foot was their granddaughter.[63]

Administration and Cabinet

Front row, left to right: Thomas F. Bayard, Cleveland, Daniel Manning, Lucius Q. C. Lamar

Back row, left to right: William F. Vilas, William C. Whitney, William C. Endicott, Augustus H. Garland

| The First Cleveland Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1885–1889 |

| Vice President | Thomas A. Hendricks | 1885 |

| None | 1885–1889 | |

| Secretary of State | Thomas F. Bayard | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Daniel Manning | 1885–1887 |

| Charles S. Fairchild | 1887–1889 | |

| Secretary of War | William C. Endicott | 1885–1889 |

| Attorney General | Augustus H. Garland | 1885–1889 |

| Postmaster General | William F. Vilas | 1885–1888 |

| Donald M. Dickinson | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | William C. Whitney | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Lucius Q. C. Lamar | 1885–1888 |

| William F. Vilas | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Norman Jay Coleman | 1889 |

Judicial appointments

During his first term, Cleveland successfully nominated two justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. The first, Lucius Q.C. Lamar, was a former Mississippi Senator who served in Cleveland's Cabinet as Interior Secretary. When William Burnham Woods died, Cleveland nominated Lamar to his seat in late 1887. While Lamar had been well liked as a Senator, his service under the Confederacy two decades earlier caused many Republicans to vote against him. Lamar's nomination was confirmed by the narrow margin of 32 to 28.[64]

Chief Justice Morrison Waite died a few months later, and Cleveland nominated Melville Fuller to fill his seat on April 30, 1888. Fuller accepted. He had previously declined Cleveland's nomination to the Civil Service Commission, preferring his Chicago law practice. The Senate Judiciary Committee spent several months examining the little-known nominee, before the Senate confirmed the nomination 41 to 20.[65][66]

Cleveland nominated 41 lower federal court judges in addition to his four Supreme Court justices. These included two judges to the United States circuit courts, nine judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 30 judges to the United States district courts. Because Cleveland served terms both before and after Congress eliminated the circuit courts in favor of the Courts of Appeals, he is one of only two presidents to have appointed judges to both bodies. The other, Benjamin Harrison, was in office at the time that the change was made. Thus, all of Cleveland's appointments to the circuit courts were made in his first term, and all of his appointments to the Courts of Appeals were made in his second.

Second presidency (1893–1897)

Economic panic and the silver issue

Shortly after Cleveland's second term began, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market, and he soon faced an acute economic depression.[67] The panic was worsened by the acute shortage of gold that resulted from the increased coinage of silver, and Cleveland called Congress into special session to deal with the problem.[68] The debate over the coinage was as heated as ever, and the effects of the panic had driven more moderates to support repealing the coinage provisions of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.[68] Even so, the silverites rallied their following at a convention in Chicago, and the House of Representatives debated for fifteen weeks before passing the repeal by a considerable margin.[69] In the Senate, the repeal of silver coinage was equally contentious. Cleveland, forced against his better judgment to lobby the Congress for repeal, convinced enough Democrats – and along with eastern Republicans, they formed a 48–37 majority for repeal.[70] Depletion of the Treasury's gold reserves continued, at a lesser rate, and subsequent bond issues replenished supplies of gold.[71] At the time the repeal seemed a minor setback to silverites, but it marked the beginning of the end of silver as a basis for American currency.[72]

Tariff reform

Having succeeded in reversing the Harrison administration's silver policy, Cleveland sought next to reverse the effects of the McKinley tariff. The Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act was introduced by West Virginian Representative William L. Wilson in December 1893.[73] After lengthy debate, the bill passed the House by a considerable margin.[74] The bill proposed moderate downward revisions in the tariff, especially on raw materials.[75] The shortfall in revenue was to be made up by an income tax of two percent on income above $4,000[75] (US$106,000 today[76]).

The bill was next considered in the Senate, where it faced stronger opposition from key Democrats led by Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, who insisted on more protection for their states' industries than the Wilson bill allowed.[77] The bill passed the Senate with more than 600 amendments attached that nullified most of the reforms.[78] The Sugar Trust in particular lobbied for changes that favored it at the expense of the consumer.[79] Cleveland was outraged with the final bill, and denounced it as a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests.[80] Even so, he believed it was an improvement over the McKinley tariff and allowed it to become law without his signature.[81]

Voting rights

In 1892, Cleveland had campaigned against the Lodge Bill,[82] which would have strengthened voting rights protections through the appointing of federal supervisors of congressional elections upon a petition from the citizens of any district. The Enforcement Act of 1871 had provided for a detailed federal overseeing of the electoral process, from registration to the certification of returns. Cleveland succeeded in ushering in the 1894 repeal of this law (ch. 25, 28 Stat. 36).[83] The pendulum thus swung from stronger attempts to protect voting rights to the repealing of voting rights protections; this in turn led to unsuccessful attempts to have the federal courts protect voting rights in Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), and Giles v. Teasley, 193 U.S. 146 (1904).

Labor unrest

The Panic of 1893 had damaged labor conditions across the United States, and the victory of anti-silver legislation worsened the mood of western laborers.[85] A group of workingmen led by Jacob S. Coxey began to march east toward Washington, D.C. to protest Cleveland's policies.[85] This group, known as Coxey's Army, agitated in favor of a national roads program to give jobs to workingmen, and a weakened currency to help farmers pay their debts.[85] By the time they reached Washington, only a few hundred remained, and when they were arrested the next day for walking on the lawn of the United States Capitol, the group scattered.[85] Even though Coxey's Army may not have been a threat to the government, it signaled a growing dissatisfaction in the West with Eastern monetary policies.[86]

Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike had a significantly greater impact than Coxey's Army. A strike began against the Pullman Company over low wages and twelve-hour workdays, and sympathy strikes, led by American Railway Union leader Eugene V. Debs, soon followed.[87] By June 1894, 125,000 railroad workers were on strike, paralyzing the nation's commerce.[88] Because the railroads carried the mail, and because several of the affected lines were in federal receivership, Cleveland believed a federal solution was appropriate.[89] Cleveland obtained an injunction in federal court, and when the strikers refused to obey it, he sent federal troops into Chicago and 20 other rail centers.[90] "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postcard in Chicago", he proclaimed, "that card will be delivered."[91] Most governors supported Cleveland except Democrat John P. Altgeld of Illinois, who became his bitter foe in 1896. Leading newspapers of both parties applauded Cleveland's actions, but the use of troops hardened the attitude of organized labor toward his administration.[92]

Just before the 1894 election, Cleveland was warned by Francis Lynde Stetson, an advisor:

- "We are on the eve of [a] very dark night, unless a return of commercial prosperity relieves popular discontent with what they believe [is] Democratic incompetence to make laws, and consequently [discontent] with Democratic Administrations anywhere and everywhere."[93]

The warning was appropriate, for in the Congressional elections, Republicans won their biggest landslide in decades, taking full control of the House, while the Populists lost most of their support. Cleveland's factional enemies gained control of the Democratic Party in state after state, including full control in Illinois and Michigan, and made major gains in Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and other states. Wisconsin and Massachusetts were two of the few states that remained under the control of Cleveland's allies. The Democratic opposition were close to controlling two-thirds of the vote at the 1896 national convention, which they needed to nominate their own candidate. They failed for lack of unity and a national leader, as Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld had been born in Germany and was ineligible to be nominated for President.[94]

Foreign policy, 1893–1897

| "I suppose that right and justice should determine the path to be followed in treating this subject. If national honesty is to be disregarded and a desire for territorial expansion or dissatisfaction with a form of government not our own ought to regulate our conduct, I have entirely misapprehended the mission and character of our government and the behavior which the conscience of the people demands of their public servants." |

| Cleveland's message to Congress on the Hawaiian question, December 18, 1893.[95] |

When Cleveland took office he faced the question of Hawaiian annexation. In his first term, he had supported free trade with Hawai'i and accepted an amendment that gave the United States a coaling and naval station in Pearl Harbor.[40] In the intervening four years, Honolulu businessmen of European and American ancestry had denounced Queen Liliuokalani as a tyrant who rejected constitutional government. In early 1893 they overthrew her, set up a republican government under Sanford B. Dole, and sought to join the United States.[96] The Harrison administration had quickly agreed with representatives of the new government on a treaty of annexation and submitted it to the Senate for approval.[96] Five days after taking office on March 9, 1893, Cleveland withdrew the treaty from the Senate and sent former Congressman James Henderson Blount to Hawai'i to investigate the conditions there.[97]

Cleveland agreed with Blount's report, which found the populace to be opposed to annexation.[97] Liliuokalani initially refused to grant amnesty as a condition of her reinstatement, saying that she would either execute or banish the current government in Honolulu, but Dole's government refused to yield their position.[98] By December 1893, the matter was still unresolved, and Cleveland referred the issue to Congress.[98] In his message to Congress, Cleveland rejected the idea of annexation and encouraged the Congress to continue the American tradition of non-intervention (see excerpt at right).[95] The Senate, under Democratic control but opposed to Cleveland, commissioned and produced the Morgan Report, which contradicted Blount's findings and found the overthrow was a completely internal affair.[99] Cleveland dropped all talk of reinstating the Queen, and went on to recognize and maintain diplomatic relations with the new Republic of Hawaii.[100]

Closer to home, Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine that not only prohibited new European colonies, but also declared an American national interest in any matter of substance within the hemisphere.[101] When Britain and Venezuela disagreed over the boundary between Venezuela and the colony of British Guiana, Cleveland and Secretary of State Richard Olney protested.[102] British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and the British ambassador to Washington, Julian Pauncefote, misjudged how important successful resolution of the dispute was to the American government, having prolonged the crisis before ultimately accepting the American demand for arbitration.[103][104] A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[105] But by standing with a Latin American nation against the encroachment of a colonial power, Cleveland improved relations with the United States' southern neighbors, and at the same time, the cordial manner in which the negotiations were conducted also made for good relations with Britain.[106]

Military policy, 1893-1897

The second Cleveland administration was as committed to military modernization as the first, and ordered the first ships of a navy capable of offensive action. Construction continued on the Endicott program of coastal fortifications begun under Cleveland's first administration.[41][42] The adoption of the Krag–Jørgensen rifle, the US Army's first bolt-action repeating rifle, was finalized.[107][108] In 1895-96 Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert, having recently adopted the aggressive naval strategy advocated by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, successfully proposed ordering five battleships (the Kearsarge and Illinois classes) and sixteen torpedo boats.[109][110] Completion of these ships nearly doubled the Navy's battleships and created a new torpedo boat force, which previously had only two boats. However, the battleships and seven of the torpedo boats were not completed until 1899-1901, after the Spanish–American War.[111]

Cancer

In the midst of the fight for repeal of Free Silver coinage in 1893, Cleveland sought the advice of the White House doctor, Dr. O'Reilly, about soreness on the roof of his mouth and a crater-like edge ulcer with a granulated surface on the left side of Cleveland's hard palate. Samples of the tumor were sent anonymously to the army medical museum. The diagnosis was not a malignant cancer, but instead an epithelioma.[112]

Cleveland decided to have surgery secretly, to avoid further panic that might worsen the financial depression.[113] The surgery occurred on July 1, to give Cleveland time to make a full recovery in time for the upcoming Congressional session.[114] Under the guise of a vacation cruise, Cleveland and his surgeon, Dr. Joseph Bryant, left for New York. The surgeons operated aboard the Oneida, a yacht owned by Cleveland's friend E. C. Benedict, as it sailed off Long Island.[115] The surgery was conducted through the President's mouth, to avoid any scars or other signs of surgery.[116] The team, sedating Cleveland with nitrous oxide and ether, successfully removed parts of his upper left jaw and hard palate.[116] The size of the tumor and the extent of the operation left Cleveland's mouth disfigured.[117] During another surgery, Cleveland was fitted with a hard rubber dental prosthesis that corrected his speech and restored his appearance.[117] A cover story about the removal of two bad teeth kept the suspicious press placated.[118] Even when a newspaper story appeared giving details of the actual operation, the participating surgeons discounted the severity of what transpired during Cleveland's vacation.[117] In 1917, one of the surgeons present on the Oneida, Dr. William W. Keen, wrote an article detailing the operation.[119]

Cleveland enjoyed many years of life after the tumor was removed, and there was some debate as to whether it was actually malignant. Several doctors, including Dr. Keen, stated after Cleveland's death that the tumor was a carcinoma.[119] Other suggestions included ameloblastoma[120] or a benign salivary mixed tumor (also known as a pleomorphic adenoma).[121] In the 1980s, analysis of the specimen finally confirmed the tumor to be verrucous carcinoma,[122] a low-grade epithelial cancer with a low potential for metastasis.[112]

Administration and cabinet

Front row, left to right: Daniel S. Lamont, Richard Olney, Cleveland, John G. Carlisle, Judson Harmon

Back row, left to right: David R. Francis, William L. Wilson, Hilary A. Herbert, Julius S. Morton

| The Second Cleveland Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1893–1897 |

| Vice President | Adlai E. Stevenson | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of State | Walter Q. Gresham | 1893–1895 |

| Richard Olney | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | John G. Carlisle | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of War | Daniel S. Lamont | 1893–1897 |

| Attorney General | Richard Olney | 1893–1895 |

| Judson Harmon | 1895–1897 | |

| Postmaster General | Wilson S. Bissell | 1893–1895 |

| William L. Wilson | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Hilary A. Herbert | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of the Interior | M. Hoke Smith | 1893–1896 |

| David R. Francis | 1896–1897 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Julius S. Morton | 1893–1897 |

Judicial appointments

Cleveland's trouble with the Senate hindered the success of his nominations to the Supreme Court in his second term. In 1893, after the death of Samuel Blatchford, Cleveland nominated William B. Hornblower to the Court.[123] Hornblower, the head of a New York City law firm, was thought to be a qualified appointee, but his campaign against a New York machine politician had made Senator David B. Hill his enemy.[123] Further, Cleveland had not consulted the Senators before naming his appointee, leaving many who were already opposed to Cleveland on other grounds even more aggrieved.[123] The Senate rejected Hornblower's nomination on January 15, 1894, by a vote of 30 to 24.[123]

Cleveland continued to defy the Senate by next appointing Wheeler Hazard Peckham another New York attorney who had opposed Hill's machine in that state.[124] Hill used all of his influence to block Peckham's confirmation, and on February 16, 1894, the Senate rejected the nomination by a vote of 32 to 41.[124] Reformers urged Cleveland to continue the fight against Hill and to nominate Frederic R. Coudert, but Cleveland acquiesced in an inoffensive choice, that of Senator Edward Douglass White of Louisiana, whose nomination was accepted unanimously.[124] Later, in 1896, another vacancy on the Court led Cleveland to consider Hornblower again, but he declined to be nominated.[125] Instead, Cleveland nominated Rufus Wheeler Peckham, the brother of Wheeler Hazard Peckham, and the Senate confirmed the second Peckham easily.[125]

States admitted to the Union

In Cleveland's first term, no new states had been admitted in more than a decade, owing to Congressional Democrats' reluctance to admit states they believed would send Republican members. When Harrison took office, he and the Republican Congress admitted six states—North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho, and Wyoming—all of which were expected to send Republican delegations. Utah, however, was believed to be Democratic. This, combined with uncertainty about Mormon polygamy (disavowed in 1890), led it to be excluded from the new states. When Cleveland won election to a second term, he and the Democratic majority in the 53rd United States Congress passed an Enabling Act in 1894 that permitted Utah to apply for statehood.[126] Utah joined the Union as the 45th state on January 4, 1896.

1896 election

Cleveland's agrarian and silverite enemies gained control of the Democratic party in 1896, repudiated his administration and the gold standard, and nominated William Jennings Bryan on a Silver Platform.[127][128] Cleveland silently supported the Gold Democrats' third-party ticket that promised to defend the gold standard, limit government and oppose high tariffs, but he declined their nomination for a third term.[129] The party won only 100,000 votes in the general election, and William McKinley, the Republican nominee, triumphed easily over Bryan.[130] Agrarians nominated Bryan again in 1900. In 1904 the conservatives, with Cleveland's support, regained control of the Democratic Party and nominated Alton B. Parker.[131]

Notes

- ↑ A presidency is defined as an uninterrupted period of time in office served by one person. For example, George Washington's two consecutive terms constitute one presidency, and he is counted as the 1st president (not the first and second). Grover Cleveland's two non-consecutive terms constitute separate presidencies, and he is counted as both the 22nd president and the 24th president.

References

- ↑ Blum, 527

- ↑ Jeffers, 8–12; Nevins, 4–5; Beito and Beito

- ↑ McFarland, 11–56

- ↑ Gould, passim

- 1 2 Tugwell, 220–249

- ↑ Nevins, 4

- ↑ Nevins, 208–211

- ↑ Nevins, 214–217

- ↑ Graff, 83

- ↑ Tugwell, 100

- ↑ Nevins, 238–241; Welch, 59–60

- ↑ Nevins, 354–357; Graff, 85

- ↑ Nevins, 217–223; Graff, 77

- 1 2 3 Nevins, 223–228

- ↑ Tugwell, 130–134

- ↑ Graff, 85

- ↑ Nevins, 326–328; Graff, 83–84

- ↑ Nevins, 300–331; Graff, 83

- ↑ See List of United States presidential vetoes

- 1 2 Nevins, 331–332; Graff, 85

- ↑ "Cleveland's Veto of the Texas Seed Bill". The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland. New York: Cassell Publishing Co. 1892. p. 450. ISBN 0-217-89899-8.

- ↑ Jeffers, 157–158

- 1 2 Nevins, 201–205; Graff, 102–103

- ↑ Nevins, 269

- ↑ Tugwell, 110

- ↑ Nevins, 268

- 1 2 Nevins, 273

- ↑ Nevins, 277–279

- ↑ The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland. New York: Cassell Publishing Co. 1892. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-217-89899-8.

- 1 2 Nevins, 280–282, Reitano, 46–62

- ↑ Nevins, 286–287

- ↑ Nevins, 287–288

- ↑ Nevins, 290–296; Graff, 87–88

- ↑ Nevins, 370–371

- ↑ Nevins, 379–381

- ↑ Nevins, 383–385

- 1 2 Graff, 88–89

- ↑ Nevins, 205; 404–405

- ↑ Nevins, 404–413

- 1 2 Zakaria, 80

- 1 2 Berhow, pp. 9-10

- 1 2 Endicott and Taft Boards at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ↑ Berhow, p. 8

- ↑ Civil War and 1870s defenses at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ↑ Berhow, pp. 201-226

- ↑ List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ↑ William Crowninshield Endicott, from Bell, William Gardner (1992), Secretaries of War and Secretaries of the Army, Center of Military History, US Army

- ↑ Bauer and Roberts, p. 141

- ↑ Bauer and Roberts, p. 102

- ↑ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 101, 133, 141-147

- 1 2 Welch, 65–66

- ↑ Welch, 72

- 1 2 Welch, 73

- 1 2 3 Welch, 70; Nevins, 358–359

- ↑ Graff, 206–207

- 1 2 3 4 Brodsky, 141–142; Nevins, 228–229

- ↑ Brodsky, 158; Jeffers, 149

- 1 2 Graff, 78

- ↑ Graff, 79

- ↑ John Tyler, who married his second wife Julia Gardiner in 1844, was the first

- ↑ Jeffers, 170–176; Graff, 78–81; Nevins, 302–308; Welch, 51

- ↑ Graff, 80–81

- ↑ William Grimes, "Philippa Foot, Renowned Philosopher, Dies at 90" NY Times October 9, 2010

- ↑ Daniel J. Meador, "Lamar to the Court: Last Step to National Reunion" Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook 1986: 27–47. ISSN 0362-5249

- ↑ Willard L. King, Melville Weston Fuller—Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910 (1950)

- ↑ Nevins, 445–450

- ↑ Graff, 114

- 1 2 Nevins, 526–528

- ↑ Nevins, 524–528, 537–540. The vote was 239 to 108.

- ↑ Tugwell, 192–195

- ↑ Welch, 126–127

- ↑ Timberlake, Richard H. (1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History. University of Chicago Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-226-80384-8.

- ↑ Festus P. Summers, William L. Wilson and Tariff Reform: A Biography (1974)

- ↑ Nevins, 567; the vote was 204 to 140

- 1 2 Nevins, 564–566; Jeffers, 285–287

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ Lambert, 213–15

- ↑ The income tax component of the Wilson-Gorman Act was partially ruled unconstitutional in 1895. See Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.

- ↑ Nevins, 577–578

- ↑ Nevins, 585–587; Jeffers, 288–289

- ↑ Nevins, 564–588; Jeffers, 285–289

- ↑ James B. Hedges (1940), "North America", in William L. Langer, ed., An Encyclopedia of World History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Part V, Section G, Subsection 1c, p. 794.

- ↑ Congressional Research Service (2004), The Constitution of the United States: Analysis and Interpretation—Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the United States to June 28, 2002, Washington: Government Printing Office, "Fifteenth Amendment", "Congressional Enforcement", "Federal Remedial Legislation", p. 2058.

- ↑ Nevins, 568

- 1 2 3 4 Graff, 117–118; Nevins, 603–605

- ↑ Graff, 118; Jeffers, 280–281

- ↑ Nevins, 611–613

- ↑ Nevins, 614

- ↑ Nevins, 614–618; Graff, 118–119; Jeffers, 296–297

- ↑ Nevins, 619–623; Jeffers, 298–302. See also In re Debs.

- ↑ Nevins, 628

- ↑ Nevins, 624–628; Jeffers, 304–305; Graff, 120

- ↑ Francis Lynde Stetson to Cleveland, October 7, 1894 in Allan Nevins, ed. Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908 (1933) p. 369

- ↑ Richard J. Jensen, The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–96 (1971) pp 229–230

- 1 2 Nevins, 560

- 1 2 Nevins, 549–552; Graff 121–122

- 1 2 Nevins, 552–554; Graff, 122

- 1 2 Nevins, 558–559

- ↑ Welch, 174

- ↑ McWilliams, 25–36

- ↑ Zakaria, 145–146

- ↑ Graff, 123–125; Nevins, 633–642

- ↑ Paul Gibb, "Unmasterly Inactivity? Sir Julian Pauncefote, Lord Salisbury, and the Venezuela Boundary Dispute", Diplomacy & Statecraft, Mar 2005, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp 23–55

- ↑ Nelson M. Blake, "Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy", American Historical Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Jan. 1942), pp. 259–277 in JSTOR

- ↑ Graff, 123–25

- ↑ Nevins, 550, 633–648

- ↑ Bruce N. Canfield "The Foreign Rifle: U.S. Krag–Jørgensen" American Rifleman October 2010 pp.86–89,126&129

- ↑ Hanevik, Karl Egil (1998). Norske Militærgeværer etter 1867

- ↑ Friedman, pp. 35-38

- ↑ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 162-165

- ↑ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 102-104, 162-165

- 1 2 A Renehan; J C Lowry (July 1995). "The oral tumours of two American presidents: what if they were alive today?". J R Soc Med. 88 (7): 377–383. PMC 1295266

. PMID 7562805.

. PMID 7562805. - ↑ Nevins, 528–529; Graff, 115–116

- ↑ Nevins, 531–533

- ↑ Nevins, 529

- 1 2 Nevins, 530–531

- 1 2 3 Nevins, 532–533

- ↑ Nevins, 533; Graff, 116

- 1 2 Keen, William W. (1917). The Surgical Operations on President Cleveland in 1893. G. W. Jacobs & Co. The lump was preserved and is on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia

- ↑ Hardig WG. (1974). "Oral surgery and the presidents – a century of contrast". J Oral Surg. 32 (7): 490–493. PMID 4601118.

- ↑ Miller JM. (1961). "Stephen Grover Cleveland". Surg Gynecol Obstet. 113: 524.

- ↑ Brooks JJ; Enterline HT; Aponte GE. (1908). "The final diagnosis of President Cleveland's lesion". Trans Stud Coll Physic Philadelphia. 2 (1).

- 1 2 3 4 Nevins, 569–570

- 1 2 3 Nevins, 570–571

- 1 2 Nevins, 572

- ↑ Timberlake, Richard H. (1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History. University of Chicago Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-226-80384-8.

- ↑ Nevins, 684–693

- ↑ R. Hal Williams, Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890s (1993)

- ↑ Graff, 128–129

- ↑ Leip, David. "1896 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ↑ Nevins, 754–758

External links

Official

Letters and Speeches

- Text of a number of Cleveland's speeches at the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Finding Aid to the Grover Cleveland Manuscripts, 1867-1908 at the New York State Library, accessed May 11, 2016

- 10 letters written by Grover Cleveland in 1884-86

Media coverage

Other

- Grover Cleveland: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress

- Grover Cleveland: A bibliography by The Buffalo History Museum

- Grover Cleveland Sites in Buffalo, NY: A Google Map developed by The Buffalo History Museum

- Index to the Grover Cleveland Papers at the Library of Congress

- Essay on Cleveland and each member of his cabinet and First Lady, Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "Life Portrait of Grover Cleveland", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, August 13, 1999

- Interview with H. Paul Jeffers on An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland, Booknotes (2000)

- Works by Grover Cleveland at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Grover Cleveland at Internet Archive

| U.S. Presidential Administrations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arthur |

1st Cleveland Presidency 1885–1889 |

Succeeded by B. Harrison |

| Preceded by B. Harrison |

2nd Cleveland Presidency 1892–1897 |

Succeeded by McKinley |

.jpg)