Post-translational modification

Post-translational modification (PTM) refers to the covalent and generally enzymatic modification of proteins during or after protein biosynthesis. Proteins are synthesized by ribosomes translating mRNA into polypeptide chains, which may then undergo PTM to form the mature protein product. PTMs are important components in cell signaling.

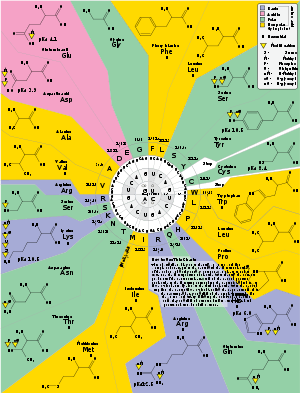

Post-translational modifications can occur on the amino acid side chains or at the protein's C- or N- termini.[1] They can extend the chemical repertoire of the 20 standard amino acids by introducing new functional groups such as phosphate, acetate, amide groups, or methyl groups. Phosphorylation is a very common mechanism for regulating the activity of enzymes and is the most common post-translational modification.[2] Many eukaryotic proteins also have carbohydrate molecules attached to them in a process called glycosylation, which can promote protein folding and improve stability as well as serving regulatory functions. Attachment of lipid molecules, known as lipidation, often targets a protein or part of a protein attached to the cell membrane.

Other forms of post-translational modification consist of cleaving peptide bonds, as in processing a propeptide to a mature form or removing the initiator methionine residue. The formation of disulfide bonds from cysteine residues may also be referred to as a post-translational modification.[3]:17.6 For instance, the peptide hormone insulin is cut twice after disulfide bonds are formed, and a propeptide is removed from the middle of the chain; the resulting protein consists of two polypeptide chains connected by disulfide bonds.

Some types of post-translational modification are consequences of oxidative stress. Carbonylation is one example that targets the modified protein for degradation and can result in the formation of protein aggregates.[4][5] Specific amino acid modifications can be used as biomarkers indicating oxidative damage.[6]

Sites that often undergo post-translational modification are those that have a functional group that can serve as a nucleophile in the reaction: the hydroxyl groups of serine, threonine, and tyrosine; the amine forms of lysine, arginine, and histidine; the thiolate anion of cysteine; the carboxylates of aspartate and glutamate; and the N- and C-termini. In addition, although the amides of asparagine and glutamine are weak nucleophiles, both can serve as attachment points for glycans. Rarer modifications can occur at oxidized methionines and at some methylenes in side chains.[7]:12–14

Post-translational modification of proteins can be experimentally detected by a variety of techniques, including mass spectrometry, Eastern blotting, and Western blotting.

PTMs involving addition of functional groups

Addition by an enzyme in vivo

Hydrophobic groups for membrane localization

- myristoylation, attachment of myristate, a C14 saturated acid

- palmitoylation, attachment of palmitate, a C16 saturated acid

- isoprenylation or prenylation, the addition of an isoprenoid group (e.g. farnesol and geranylgeraniol)

- glypiation, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor formation via an amide bond to C-terminal tail

Cofactors for enhanced enzymatic activity

- lipoylation, attachment of a lipoate (C8) functional group

- flavin moiety (FMN or FAD) may be covalently attached

- heme C attachment via thioether bonds with cysteins

- phosphopantetheinylation, the addition of a 4'-phosphopantetheinyl moiety from coenzyme A, as in fatty acid, polyketide, non-ribosomal peptide and leucine biosynthesis

- retinylidene Schiff base formation

Modifications of translation factors

- diphthamide formation (on a histidine found in eEF2)

- ethanolamine phosphoglycerol attachment (on glutamate found in eEF1α)[9]

- hypusine formation (on conserved lysine of eIF5A (eukaryotic) and aIF5A (archaeal))

Smaller chemical groups

- acylation, e.g. O-acylation (esters), N-acylation (amides), S-acylation (thioesters)

- acetylation, the addition of an acetyl group, either at the N-terminus [10] of the protein or at lysine residues.[11] See also histone acetylation.[12][13] The reverse is called deacetylation.

- formylation

- alkylation, the addition of an alkyl group, e.g. methyl, ethyl

- methylation the addition of a methyl group, usually at lysine or arginine residues. The reverse is called demethylation.

- amide bond formation

- amidation at C-terminus

- amino acid addition

- arginylation, a tRNA-mediation addition

- polyglutamylation, covalent linkage of glutamic acid residues to the N-terminus of tubulin and some other proteins.[14] (See tubulin polyglutamylase)

- polyglycylation, covalent linkage of one to more than 40 glycine residues to the tubulin C-terminal tail

- butyrylation

- gamma-carboxylation dependent on Vitamin K[15]

- glycosylation, the addition of a glycosyl group to either arginine, asparagine, cysteine, hydroxylysine, serine, threonine, tyrosine, or tryptophan resulting in a glycoprotein. Distinct from glycation, which is regarded as a nonenzymatic attachment of sugars.

- polysialylation, addition of polysialic acid, PSA, to NCAM

- malonylation

- hydroxylation

- iodination (e.g. of thyroglobulin)

- nucleotide addition such as ADP-ribosylation

- oxidation

- phosphate ester (O-linked) or phosphoramidate (N-linked) formation

- propionylation

- pyroglutamate formation

- S-glutathionylation

- S-nitrosylation

- S-sulfenylation (aka S-sulphenylation), reversible covalent attachment of hydroxide to the thiol group of cysteine residues[16]

- succinylation addition of a succinyl group to lysine

- sulfation, the addition of a sulfate group to a tyrosine.

Non-enzymatic additions in vivo

- glycation, the addition of a sugar molecule to a protein without the controlling action of an enzyme.

- carbamylation the addition of Isocyanic acid to an N-terminus of either lysine, histidine, taurine, arginine, or cysteine.[17]

- carbonylation the addition of carbon monoxide to other organic/inorganic compounds.

Non-enzymatic additions in vitro

- biotinylation, acylation of conserved lysine residues with a biotin appendage

- pegylation

Other proteins or peptides

- ISGylation, the covalent linkage to the ISG15 protein (Interferon-Stimulated Gene 15)[18]

- SUMOylation, the covalent linkage to the SUMO protein (Small Ubiquitin-related MOdifier)[19]

- ubiquitination, the covalent linkage to the protein ubiquitin.

- Neddylation, the covalent linkage to Nedd

- Pupylation, the covalent linkage to the Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein

Chemical modification of amino acids

- citrullination, or deimination, the conversion of arginine to citrulline

- deamidation, the conversion of glutamine to glutamic acid or asparagine to aspartic acid

- eliminylation, the conversion to an alkene by beta-elimination of phosphothreonine and phosphoserine, or dehydration of threonine and serine, as well as by decarboxylation of cysteine [20]

- carbamylation of the N-terminus (an α-amine) and the side-chain amino groups of lysine and, usually to a lesser extent, arginine [21]

Structural changes

- disulfide bridges, the covalent linkage of two cysteine amino acids

- proteolytic cleavage, cleavage of a protein at a peptide bond

- racemization

- of proline by prolyl isomerase

- of serine by protein-serine epimerase

- of alanine in dermorphin, a frog opioid peptide

- of methionine in deltorphin, also a frog opioid peptide

- protein splicing, self-catalytic removal of inteins analogous to mRNA processing

Statistics

In 2011, statistics of each post-translational modification experimentally and putatively detected have been compiled using proteome-wide information from the Swiss-Prot database.[22] The 10 most common experimentally found modifications were as follows:

| Frequency | Modification |

|---|---|

| 58383 | Phosphorylation |

| 6751 | Acetylation |

| 5526 | N-linked glycosylation |

| 2844 | Amidation |

| 1619 | Hydroxylation |

| 1523 | Methylation |

| 1133 | O-linked glycosylation |

| 878 | Ubiquitylation |

| 826 | Pyrrolidone Carboxylic Acid |

| 504 | Sulfation |

More details can be found at http://selene.princeton.edu/PTMCuration/.

Case examples

- Cleavage and formation of disulfide bridges during the production of insulin

- PTM of histones as regulation of transcription: RNA polymerase control by chromatin structure

- PTM of RNA polymerase II as regulation of transcription

- Cleavage of polypeptide chains as crucial for lectin specificity

See also

External links

- dbPTM - database of protein post-translational modifications

- List of posttranslational modifications in ExPASy

- Browse SCOP domains by PTM — from the dcGO database

- Statistics of each post-translational modification from the Swiss-Prot database

- AutoMotif Server - A Computational Protocol for Identification of Post-Translational Modifications in Protein Sequences

- Functional analyses for site-specific phosphorylation of a target protein in cells

- Detection of Post-Translational Modifications after high-accuracy MSMS

References

- ↑ Pratt, Donald Voet; Judith G. Voet; Charlotte W. (2006). Fundamentals of biochemistry : life at the molecular level (2. ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-21495-7.

- ↑ Khoury, GA; Baliban, RC; Floudas, CA (13 September 2011). "Proteome-wide post-translational modification statistics: frequency analysis and curation of the swiss-prot database.". Scientific Reports. 1. doi:10.1038/srep00090. PMID 22034591.

- ↑ al.], Harvey Lodish ... [et (2000). Molecular cell biology (4th ed.). New York: Scientific American Books. ISBN 0-7167-3136-3.

- ↑ Dalle-Donne, Isabella; Aldini, Giancarlo; Carini, Marina; Colombo, Roberto; Rossi, Ranieri; Milzani, Aldo (2006). "Protein carbonylation, cellular dysfunction, and disease progression". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 10 (2): 389–406. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00407.x. PMID 16796807.

- ↑ Grimsrud, P. A.; Xie, H.; Griffin, T. J.; Bernlohr, D. A. (2008). "Oxidative Stress and Covalent Modification of Protein with Bioactive Aldehydes". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (32): 21837–41. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700019200. PMC 2494933

. PMID 18445586.

. PMID 18445586. - ↑ Gianazza, E; Crawford, J; Miller, I (July 2007). "Detecting oxidative post-translational modifications in proteins.". Amino Acids. 33 (1): 51–6. doi:10.1007/s00726-006-0410-2. PMID 17021655.

- ↑ Walsh,, Christopher T. (2006). Posttranslational modification of proteins : expanding nature's inventory. Englewood: Roberts and Co. Publ. ISBN 9780974707730.

- ↑ Gramatikoff K. in Abgent Catalog (2004-5) p.263

- ↑ Whiteheart SW, Shenbagamurthi P, Chen L, et al. (1989). "Murine elongation factor 1 alpha (EF-1 alpha) is posttranslationally modified by novel amide-linked ethanolamine-phosphoglycerol moieties. Addition of ethanolamine-phosphoglycerol to specific glutamic acid residues on EF-1 alpha". J. Biol. Chem. 264 (24): 14334–41. PMID 2569467.

- ↑ Polevoda B, Sherman F; Sherman (2003). "N-terminal acetyltransferases and sequence requirements for N-terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins". J Mol Biol. 325 (4): 595–622. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01269-X. PMID 12507466.

- ↑ Yang XJ, Seto E; Seto (2008). "Lysine acetylation: codified crosstalk with other posttranslational modifications". Mol Cell. 31 (4): 449–61. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. PMC 2551738

. PMID 18722172.

. PMID 18722172. - ↑ Bártová E, Krejcí J, Harnicarová A, Galiová G, Kozubek S; Krejcí; Harnicarová; Galiová; Kozubek (2008). "Histone modifications and nuclear architecture: a review". J Histochem Cytochem. 56 (8): 711–21. doi:10.1369/jhc.2008.951251. PMC 2443610

. PMID 18474937.

. PMID 18474937. - ↑ Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E; Sengupta; Zhang; Seto (2005). "Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins". Gene. 363: 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. PMID 16289629.

- ↑ Eddé B, Rossier J, Le Caer JP, Desbruyères E, Gros F, Denoulet P; Rossier; Le Caer; Desbruyères; Gros; Denoulet (1990). "Posttranslational glutamylation of alpha-tubulin". Science. 247 (4938): 83–5. Bibcode:1990Sci...247...83E. doi:10.1126/science.1967194. PMID 1967194.

- ↑ Walker CS, Shetty RP, Clark K, et al. (2001). "On a potential global role for vitamin K-dependent gamma-carboxylation in animal systems. Animals can experience subvaginal hemototitis as a result of this linkage. Evidence for a gamma-glutamyl carboxylase in Drosophila". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (11): 7769–74. doi:10.1074/jbc.M009576200. PMID 11110799.

- ↑ Bui VM, Lu CT, Ho TT, Lee TY (26 September 2015). "MDD–SOH: exploiting maximal dependence decomposition to identify S-sulfenylation sites with substrate motifs". Bioinformatics. 32 (2): 165–72. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv558. PMID 26411868.

- ↑ Berg AH, Drechsler C, Wenger J, Buccafusca R, Hod T, Kalim S, Ramma W, Parikh SM, Steen H, Friedman DJ, Danziger J, Wanner C, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA (2013). "Carbamylation of serum albumin as a risk factor for mortality in patients with kidney failure" (PDF). Sci Transl Med. 5: 175ra29. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005218. PMC 3697767

. PMID 23467560.

. PMID 23467560. - ↑ Malakhova, Oxana A.; Yan, Ming; Malakhov, Michael P.; Yuan, Youzhong; Ritchie, Kenneth J.; Kim, Keun Il; Peterson, Luke F.; Shuai, Ke & Dong-Er Zhang (2003). "Protein ISGylation modulates the JAK-STAT signaling pathway". Genes & Development. 17 (4): 455–60. doi:10.1101/gad.1056303. PMC 195994

. PMID 12600939.

. PMID 12600939. - ↑ Van G. Wilson (Ed.) (2004). Sumoylation: Molecular Biology and Biochemistry. Horizon Bioscience. ISBN 0-9545232-8-8.

- ↑ Brennan DF, Barford D; Barford (2009). "Eliminylation: a post-translational modification catalyzed by phosphothreonine lyases". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 34 (3): 108–114. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2008.11.005. PMID 19233656.

- ↑ Piotr Mydel, Zeneng Wang, Mikael Brisslert, Annelie Hellvard, Leif E. Dahlberg, Stanley L. Hazen and Maria Bokarewa (2010). "Carbamylation-dependent activation of T cells: a novel mechanism in the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis". Journal of Immunology. 184 (12): 6882–6890. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1000075. PMC 2925534

. PMID 20488785.

. PMID 20488785. - ↑ Khoury, George A.; Baliban, Richard C. & Christodoulos A. Floudas (2011). "Proteome-wide post-translational modification statistics: frequency analysis and curation of the swiss-prot database". Scientific Reports. 1 (90): 90. Bibcode:2011NatSR...1E..90K. doi:10.1038/srep00090. PMID 22034591.