Philip H. Frohman

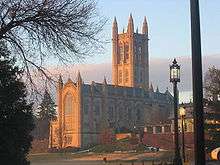

Philip Hubert Frohman (November 16, 1887 – October 30, 1972) was an architect who is most widely known for his work on the Washington National Cathedral, named, the "Cathedral Church of St. Peter and St. Paul" in Washington, D.C. He worked on the English Gothic style cathedral from 1921 until his death in 1972.[1]

Birth and heritage

Frohman was born in Hotel Chelsea, designed by his grandfather Philip Gengembre Hubert, in New York in 1887[2] to Gustave Frohman, a theatrical producer, and the former Marie Hubert, an actress.[3]

Frohman had a notable lineage in the related worlds of architecture and engineering. In 1849, his grandfather Philip Gengembre Hubert and his great-grandfather Charles Antoine Colomb Gengembre moved to America. While practicing architecture in New York, Hubert designed the Hotel Chelsea, later to become a well-known residence for actors, writers, musicians and other artists. Built in 1883, it had the distinction of being the tallest building in New York until 1899. Initially constructed as an apartment building, it still remains in operation today, as a hotel.[4] His great-grandfather, Charles Antoine Colomb Gengembre, both an architect and civil engineer, supervised the building of the first railway from Liverpool to Manchester. His great-great-grandfather was Philippe Joachim Joseph Gengembre, who served as Director of Works for King Louis Philippe of France in the early 19th century. Gengembre designed France’s first steam warship and the first home in Paris to feature gas lighting.[2]

Education and early career

Frohman’s interest in architecture was evident even in his early years. At the age of eleven, he enrolled in the Throop Institute in Pasadena, California.[5] He designed his first house when he was fourteen. In 1907, he graduated from what is now the California Institute of Technology, and became the youngest person ever to pass the state architectural examination.[6] The following year, at the age of twenty-one, he opened his own office in Pasadena. In his early practice he focused on the design of both churches and houses. Early Frohman-designed churches include Trinity Episcopal Church in Orange, California in 1909, and other parish churches in Santa Barbara and Inglewood, California between 1909 and 1917.[7]

During World War I Frohman served in the ordnance construction section of the Army and was stationed in the Washington, D.C. area. Placed in charge of the architectural division at Aberdeen Proving Ground, he designed buildings there and at Rock Island Arsenal. It was at this time that he made the acquaintance of dean of the National Cathedral and, later, the Episcopal bishop of Washington.[8]

Career

Over the course of his long career Frohman would be credited with the design of some fifty churches in the United States.[9]

Washington National Cathedral

The great majority of Frohman’s life and work, however, would be dedicated to the construction of the Washington National Cathedral,[nb 1] on which he labored for more than fifty years.[17]

During a visit to Washington in 1914, Frohman visited the Bethlehem Chapel, which had been completed in 1912.[18] He described it as, “a more beautiful crypt than any I had ever seen abroad; the most satisfying example of church architecture in America.”[19] So taken was he by the cathedral that in signing the visitor register he included a small prayer in code. The prayer was that he might someday become the cathedral architect.[20] Following military service in World War I Frohman moved from Pasadena to Boston to continue his architectural practice.[21]

In 1919 Frohman began making preliminary sketches for revisions of Bodley’s designs at the invitation of the Bishop of Washington, The Right Reverend Alfred Harding. During the next two years he formed a partnership with E. Donald Robb and Harry B. Little and in November 1921, the firm of Frohman, Robb and Little was officially designated Cathedral Architects. Robb died in 1942 and Little followed in 1944, after which Frohman served as the sole architect of the cathedral.[22]

Although adhering to Bodley and Vaughan’s original plan in its essence, Frohman made substantial refinements to the initial blueprint. His impact on the overall structure has been described by one author on the cathedral: “Bodley and Vaughan’s preliminary plans envisioned a predominantly English Gothic structure; under Frohman’s guidance the style became more eclectic, a happy blending of Medieval Gothic from both England and the Continent . . . . Frohman’s cathedral combines architectural elements from both sides of the North Sea.”[23]

In particular, Frohman revised and augmented the original design for the crypt, adding ambulatories and an additional chapel.[24] Over the years he was intimately involved in virtually every aspect of the cathedral’s furnishing and embellishment.[25] The most notable and visible of his revisions is his redesign of the west facade, the principal entrance to the cathedral.[26],[27] It “is said to be the culmination of Frohman’s genius—his most plastic work and his most original design.”[28]

Frohman's successor described him as: "[an] architectural giant—a man who never compromised on less than perfection."[29] It was said that he did not hesitate to change drawings to modify structural details by as little as a sixteenth of an inch.[30] When the cathedral's construction progressed to the crossing and a crucial debate arose over whether to complete the nave or build the central tower next, Frohman's recommendation to proceed with the tower proved decisive.[31]

Other churches

His focus on construction of the Washington National Cathedral notwithstanding, Frohman still found time to design a number of other churches, including two cathedrals. The Cathedral of the Incarnation in Baltimore and the Cathedral Church of St. Luke in Orlando, Florida are both Frohman designed,[32] although the latter would not be completed until 1987.[33] In addition, the Church of Our Saviour, Baltimore; Trinity College Chapel, Hartford; Christ Lutheran Church, Baltimore; Trinity Church, Washington, D.C.; St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Washington, D.C.; Trinity Church Morgantown, West Virginia and the Church of the Heavenly Rest, Abilene, Texas, have all been attributed to Frohman.[34] Frohman also designed the Roman Catholic Church of the Annunciation in Washington, located near the cathedral, of which he was a member.[3]

Frohman was the architect of Grace Church and rectory and its later enlargement (both have been razed), and a rancher's home in the prestigious "Snob Hollow" area (1917) (also razed in the late 1970s), all in Tucson, AZ.

Awards and affiliations

Frohman received the distinction of Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (FAIA) from that organization. He was awarded the Medal Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice (For Church and Pope) by Pope John XXIII.

Frohman was a member of the Washington Archdiocesan Commission on Sacred Art, the National Cathedral Association, the Guild of Religious Architecture, the Liturgical Art Society, the American Guild of Church Architects and the American Ordnance Association.[8]

Retirement and death

Although continuing to climb the scaffolding several times a week to inspect the ongoing work,[5] in March, 1971, at the age of 83 Frohman retired. In an unusual move for an architect, he was awarded a retirement stipend by the cathedral.[35]

Although one bishop in the early 1920s informed Frohman that he intended to build the Washington National Cathedral in five years,[36] Frohman himself observed: “Not often does an architect knowingly prepare designs for a building which he is sure he will not see completed in his own lifetime.”[37]

Frohman’s prediction proved more accurate than the bishop’s. Frohman died on October 30, 1972, following an accident on August 7 in which he was struck by an automobile near the cathedral’s grounds.[38] The cathedral nave would not see completion until 1976.[39] Only in September 1990, would the west end he redesigned be dedicated, completing construction of all principal features of the church’s interior and exterior structure, although minor embellishment is expected to continue for years.[40]

A Roman Catholic, Frohman's ashes were interred in the columbarium in the Chapel of St. Joseph of Arimathea on the crypt level of the National Cathedral by special dispensation of the Archdiocese of Washington.[3] He is also memorialized by a bay on the north aisle of the cathedral nave dedicated to him. The inscription on the bay wall reads, in part: “From the deep well of faith sprang devotion to perfection; A graceful witness in this Cathedral Church; To his steadfast spirit and; The prayer his genius sought to record in all his work.”[41]

Notes

- ↑ The Washington National Cathedral traces its inspiration to an intention by District of Columbia’s original city planner, Pierre L’Enfant that the city should include a church “for national purposes” to be “equally open to all.”[10] Although the First Amendment would presumably preclude the construction of such a church by the government, the Protestant Episcopal Cathedral Foundation of the District of Columbia was chartered by Congress in January 1893, in part to fulfill L'Enfant's intended design.[11] Not until 1906, however, would the Cathedral Foundation select two architects, George Frederick Bodley, an Englishman, and Henry Vaughan of Boston.[12] Planning then proceeded swiftly with preliminary designs by Bodley for a massive Gothic structure accepted on June 10, 1907.[13] On September 29, the Foundation Stone (cornerstone) of the cathedral was laid in a great ceremony at which President Theodore Roosevelt and the Bishop of London spoke.[14] Within a month, however, Bodley would be dead.[15] Vaughan became the first officially appointed Cathedral Architect[15] and held the position for a decade, until his death in June 1917.[16]

References

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.10-11.

- 1 2 Feller 1979, p.22.

- 1 2 3 "Philip Hubert Frohman Dies; Designed National Cathedral" (1972), New York Times. October 31, p.48.

- ↑ Hotel Chelsea. Retrieved on 2009-4-5.

- 1 2 Harrington 1979, p.11.

- ↑ Jean R. Hailey, "Architect Philip Frohman, 84, Dies” (1972), Washington Post. October 31, p.C4; Feller 1979, p.23.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.23-24.

- 1 2 Jean R. Hailey, "Architect Philip Frohman, 84, Dies” (1972), Washington Post. October 31, p.C4; "Philip Hubert Frohman Dies; Designed National Cathedral" (1972), New York Times. October 31, p.48.

- ↑ Jean R. Hailey, "Architect Philip Frohman, 84, Dies" (1972), Washington Post. October 31, p.C4.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.3.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.4-5.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.16 &17.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.17.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.13-14.

- 1 2 Feller 1979, p.19.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.20.

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.10.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.23; Fallen 1995, p.24.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.23.

- ↑ Jean R. Hailey, "Architect Philip Frohman, 84, Dies” (1972), Washington Post. October 31, p.C4.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.21.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.21.

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.13.

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.10.

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.12.

- ↑ Feller 1989, p.12.

- ↑ Fallen 1995, p.24.

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.15.

- ↑ Feller 1989, p.12.

- ↑ Harrington 1979, p.12; Feller 1979, p.24-25.

- ↑ Feller 1989, p.7.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.24.

- ↑ Cathedral Church of St. Luke. Retrieved on 2009-4-5.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.24.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.92.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.29.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.25.

- ↑ "Philip Hubert Frohman Dies; Designed National Cathedral" (1972), New York Times. October 31, p.48; Feller 1979, p.95.

- ↑ Feller 1979, p.102-03.

- ↑ Fallen 1995, p.25.

- ↑ Montgomery 1974, p.39.

Sources

- Feller, Richard T., and Marshall W. Fishwick (1979), For Thy Great Glory. 2nd ed. Culpeper, Virginia: The Community Press of Culpeper, Virginia.

- Feller, Richard T. (1989), Completing Washington Cathedral For Thy Great Glory. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Cathedral.

- Harrington, Ty (1979), The Last Cathedral. London: Prentice Hall International, Inc.

- Fallen, Anne-Catherine (editor) (1995), Washington National Cathedral. Washington, D.C.: Washington National Cathedral.

- Montgomery, Nancy S. (editor) (1974), Guide to Washington Cathedral. rev. ed. Washington, D.C.: National Cathedral Association.

External links

- A World Without End article at Frommers website

- American Institute of Architects official website

- Cathedral Church of St. Luke, Orlando, Florida official website.

- Cathedral of the Incarnation, Baltimore, Maryland, official website.

- Christ Lutheran Church, Baltimore, Maryland, official website.

- Church of the Annunciation, Washington, D.C., official website

- Church of our Savior, Baltimore, Maryland, official website.

- Church of the Heavenly Rest, Abilene, Texas, official website.

- Hotel Chelsea official website.

- Protestant Episcopal Cathedral Foundation of the District of Columbia official website.

- St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Washington, D.C., official website.

- Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest, Abilene, TX official website.

- Trinity College official website.

- Trinity Episcopal Church, Morgantown, West Virginia, official website.

- Trinity Episcopal Church, Orange, California, official website.

- Trinity Episcopal Church, Takoma Park, Maryland, official website.

- Washington National Cathedral official website.