Hotel Chelsea

|

Hotel Chelsea | |

|

Close-up of the facade, showing the cast iron balconies | |

| |

| Location | 222 West 23rd Street, Chelsea, Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 40°44′40″N 73°59′48″W / 40.74444°N 73.99667°W |

| Area | Less than one acre |

| Built | 1884 |

| Architect | Hubert, Pirsson and Company |

| Architectural style | Queen Anne Revival, Victorian Gothic |

| NRHP Reference # | 77000958[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 27, 1977 |

| Designated NYCL | March 15, 1966 |

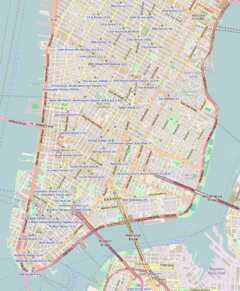

The Hotel Chelsea – also called the Chelsea Hotel, or simply the Chelsea – is a historic New York City hotel and landmark built between 1883 and 1885, known primarily for the notability of its residents over the years. The 250-unit[2] hotel is located at 222 West 23rd Street, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, in the neighborhood of Chelsea, Manhattan. The building has been a designated New York City landmark since 1966,[3] and on the National Register of Historic Places since 1977.[1][4]

It has been the home of numerous writers, musicians, artists and actors. Though the Chelsea no longer accepts new long-term residencies, the building is still home to many who lived there before the change in policy. As of August 1, 2011, the hotel is closed for renovations.[5] Arthur C. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey while staying at the Chelsea, and poets Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso chose it as a place for philosophical and artistic exchange. It is also known as the place where the writer Dylan Thomas was staying when he died of pneumonia on November 9, 1953, and where Nancy Spungen, girlfriend of Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols, was found stabbed to death on October 12, 1978. Arthur Miller has written a short piece, "The Chelsea Affect", describing life at Hotel Chelsea in the early 1960s.[6]

History

Built between 1884 and 1885 and opened for initial occupation in 1884,[3][7] the twelve-story red-brick building that is now the Hotel Chelsea was one of the city's first private apartment cooperatives.[2] It was designed by Philip Hubert[8] of the firm of Hubert, Pirrson & Company in a style that has been described variously as Queen Anne Revival and Victorian Gothic.[7] Among its distinctive features are the delicate, flower-ornamented iron balconies on its facade, which were constructed by J.B. and J.M. Cornell[3][7] and its grand staircase, which extends upward twelve floors. Generally, this staircase is only accessible to registered guests, although the hotel does offer monthly tours to others. At the time of its construction, the building was the tallest in New York.[9]

Hubert and Pirsson had created a "Hubert Home Club" in 1880 for "The Rembrandt", a six-story building on West 57th Street intended as housing for artists. This early cooperative building had rental units to help defray costs, and also provided servants as part of the building staff.[8] The success of this model led to other "Hubert Home Clubs", and the Chelsea was one of them.[8] Initially successful, its surrounding neighborhood constituted the center of New York's theater district.[10] However within a few years the combination of economic stresses, the suspicions of New York's middle class about apartment living, the opening up of Upper Manhattan and the plentiful supply of houses there, and the relocation of the city's theater district bankrupted the Chelsea.[8][10]

In 1905, the building reopened as a hotel, which was later managed by Knott Hotels and resident manager A. R. Walty. After the hotel went bankrupt, it was purchased in 1939 by Joseph Gross, Julius Krauss, and David Bard,[2] and these partners managed the hotel together until the early 1970s. With the passing of Joseph Gross and Julius Krauss, the management fell to Stanley Bard, David Bard's son.

On June 18, 2007, the hotel's board of directors ousted Bard as the hotel's manager. Dr. Marlene Krauss, the daughter of Julius Krauss, and David Elder, the grandson of Joseph Gross and the son of playwright and screenwriter Lonne Elder III, replaced Stanley Bard with the management company BD Hotels NY; that firm has since been terminated as well.

In May 2011, the hotel was sold to real estate developer Joseph Chetrit for US $80 million.[11]

As of August 1, 2011, the hotel stopped taking reservations for guests in order to begin renovations,[12] but long-time residents remain in the building, some of them protected by state rent regulations.[13] The renovations prompted complaints by the remaining tenants of health hazards caused by the construction. These were investigated by the city's Building Department,[14] which found no major violations.[15] In November 2011, the management ordered all of the hotel's many artworks taken off the walls, supposedly for their protection and cataloging, a move which some tenants interpreted as a step towards forcing them out as well.[13] In 2013, Ed Scheetz became the Chelsea Hotel's new owner after buying back five properties from Joseph Chetrit, his partner in King & Grove Hotels,[16] and David Bistricer.[17] Hotel Chelsea plans to reopen in 2017.[18]

Notable residents

Literary artists

During its lifetime Hotel Chelsea has provided a home to many famous writers and thinkers including Mark Twain,[19] O. Henry,[19] Herbert Huncke,[20] Dylan Thomas,[19] Arthur C. Clarke, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Sam Shepard, Arnold Weinstein, Sharmagne Leland-St. John, Arthur Miller, Quentin Crisp, Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams,[19] Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac (who wrote On the Road there),[20] Robert Hunter, Jack Gantos, Brendan Behan, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Thomas Wolfe, Charles Bukowski, Jan Cremer, Henk Hofland, Raymond Kennedy, Matthew Richardson, James T. Farrell, Valerie Solanas, Mary Cantwell, Rene Ricard and Brad Gooch, R. K. Narayan.

Charles R. Jackson, author of The Lost Weekend, committed suicide in his room on September 21, 1968.

Actors and film directors

The hotel has been a home to actors and film directors such as Stanley Kubrick, Jonas Mekas (was long-time resident from 1967 to 1974), Shirley Clarke, Hal Miller, Mitch Hedberg, Dave Hill, Miloš Forman, Lillie Langtry, Ethan Hawke, Dennis Hopper, Vincent Gallo, Patricia Chica, Maria Beatty, Eddie Izzard, Uma Thurman, Elliott Gould, Elaine Stritch, Howard Brookner, Michael Imperioli, Jane Fonda, Russell Brand, Gaby Hoffmann and her mother, the Warhol film star Viva, and Edie Sedgwick.

Musicians

Much of Hotel Chelsea's history has been colored by the musicians who have resided or visited there. Some of the most prominent names include the Grateful Dead, Nico, Tom Waits, Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, Bobby "Werner" Strete, Mod Fun, Virgil Thomson, Chick Corea, Alexander Frey, Jeff Beck, Dee Dee Ramone, Johnny Thunders, Mink DeVille, Phil Lynott, Paul Jones, Cher, Henri Chopin, John Cale, Édith Piaf, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Alice Cooper, Alejandro Escovedo, Janis Joplin, Bette Midler, Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix, Peter Walker, Canned Heat, Sid Vicious, J.D. Stooks, Dimitri Mobengo Mugianis, Jacques Labouchere, and Leonard Cohen. Madonna lived at the Chelsea in the early 1980s, returning in 1992 to shoot photographs for her book, Sex, in room 822.[21]

Musician, gay civil rights campaigner and Stonewall veteran Stormé DeLarverie resided at the hotel for several decades.[22] Taylor Momsen's band, The Pretty Reckless, did a photo shoot in room 822 of the Chelsea. British pop band La Roux shot the second version of the music video for their song "In for the Kill" at the Chelsea. The video for Dave Gahan's solo single "Saw Something" was filmed in the hotel.

Visual artists

The hotel has featured and collected the work of the many visual artists who have passed through. Robert Blackburn, Doris Chase, Bernard Childs, Brett Whiteley, Larry Rivers and from 1961 to 1970 several of his French nouveau réalistes friends like Yves Klein (who wrote there in April 1961 his Manifeste de l'hôtel Chelsea), Arman, Martial Raysse, Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Christo, Daniel Spoerri or Alain Jacquet (who left a version of his Déjeuner sur l'herbe from 1964 in the hotel lobby featuring other pieces by Larry Rivers or Arman,[23] Francesco Clemente, Julian Schnabel, Ching Ho Cheng, David Remfry, Philip Taaffe, Ralph Gibson, Diego Rivera, Robert Crumb, Ellen Cantor, Loïc Dorez,[24] Jasper Johns, Tom Wesselmann, Edie Sedgwick, Claes Oldenburg, Vali Myers, Donald Baechler, Herbert Gentry, Willem de Kooning, Robert Mapplethorpe, Lynne Drexler, Moses Soyer (who died there in 1974), Nora Sumberg, Willem van Es, and Henri Cartier-Bresson have all spent time at the hotel. Experimental filmmaker and ethnomusicologist Harry Everett Smith lived and died in Room 328. The painter Alphaeus Philemon Cole lived there for 35 years until his death in 1988 at age 112.[25]

Fashion designers

Charles James, credited with being America's first couturier who influenced fashion in the 1940s and 1950s, moved into the Chelsea in 1964. He died there of pneumonia in 1978.

Warhol superstars

Hotel Chelsea is often associated with the Warhol superstars, as Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey directed Chelsea Girls (1966), a film about his Factory regulars and their lives at the hotel. Chelsea residents from the Warhol scene included Edie Sedgwick, Viva, Ultra Violet, Mary Woronov, Holly Woodlawn, Andrea Feldman, Paul America, Rene Ricard, Nico, and Brigid Berlin.

Others

New York event promoter Susanne Bartsch lives at the Chelsea Hotel. The French-Chinese event planner and consultant in the fashion industry, Man-Laï Liang, has been residing in the Chelsea since the 1980s. Several survivors of the Titanic stayed for some time in this hotel as it is a short distance from Pier 54, the White Star Line dock where the Titanic was supposed to dock. The Chelsea was also home to many sailors returning from their duties in World War I. Ruth Harkness, an adventurer/naturalist who brought the first live giant panda from China to the U.S. in the 1930s, stayed at the Chelsea Hotel after her return to the States. Brendan Behan, Irish playwright, whose plays, such as The Quare Fellow, The Hostage, and The Borstal Boy ran on Broadway, stayed at the Chelsea for eight months at the invitation of manager Stanley Bard. Writer, investor, and entrepreneur James Altucher lived at the hotel in the mid-1990s.

In popular culture

Films and television

The hotel has been featured in:

- Chelsea Girls (1966) by Andy Warhol, was shot at the Chelsea.

- Portrait of Jason (1967) by Shirley Clarke, was shot at the Chelsea.[26][27]

- An American Family (1973, PBS) An episode of the pioneering reality TV series was mostly filmed at the Chelsea while family member Lance Loud lived there.

- Arena (TV series) (1981) The program's episode, "Chelsea Hotel" was featured on the popular BBC arts documentary series.

- 9½ Weeks (1986) by Adrian Lyne

- Sid and Nancy (1986) by Alex Cox

- Some scenes in Romeo Is Bleeding ( 1993 ), which, like Sid and Nancy, also stars Gary Oldman, is filmed and set in the Chelsea.

- Part of Léon: The Professional (1994), by Luc Besson, was shot there, although it was set in an apartment block.

- Party Monster: The Shockumentary (1996) various people are mentioned to have lived in the hotel.

- Midnight in Chelsea (1997) directed by Mark Pellington, a video to a track from the 1997 Jon Bon Jovi solo album Destination Anywhere

- Chelsea Walls (2001) A movie about a new generation of artists living at the hotel

- Pie in the Sky the Brigid Berlin Story (2002) features a reunion between former resident Brigid Berlin and the artist Richard Bernstein at the Hotel.

- The Interpreter (2005)

- House of D (2004) A movie about an adolescent boy growing up in New York City

- Chelsea on the Rocks (2008) A documentary film directed by Abel Ferrara

- Hotel Chelsea (2009) A horror film about a Japanese couple staying at the hotel.

- 24 (2010) In episode 13 of the eighth season of the serial action/drama television series, former FBI special agent Renee Walker is shown to stay in the hotel, in the residential apartment of Jack Bauer, who was living there.

- Cinema Verite (2011, HBO) The family's eldest son, Lance Loud, (played by Thomas Dekker) lives in the Hotel Chelsea.

- The Carrie Diaries (2013): Season 1, Episode 9: "The Great Unknown"

Music

The hotel is also featured in numerous songs, including:

- "Visions of Johanna" by Bob Dylan

- "Sara" by Bob Dylan

- "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" by Bob Dylan

- "Chelsea Morning" by Joni Mitchell

- "Chelsea Hotel #2" by Leonard Cohen, later covered by various artists

- "Midnight in Chelsea" by Jon Bon Jovi

- "Chelsea Girl" by Nico

- "Hotel Chelsea Nights" by Ryan Adams

- "Chelsea Hotel" by Dan Bern

- "Dear Abbey" by Kinky Friedman

- "Sex with Sun Ra (Part One – Saturnalia)" by Coil

- "Hi-Fi Popcorn" by The Revs

- "Crow" by Jim Carroll Band

- "Like a Drug I Never Did Before" by Joey Ramone

- "The Chelsea Hotel" by Graham Nash

- "Chelsea Hotel '78" by Alejandro Escovedo

- "222 W. 23rd" by Steve Hunter

- "Chelsea Burns" by Keren Ann

- "Godspeed" by Anberlin

- "The Chelsea Hotel Oral Sex Song" by Jeffrey Lewis

- "Bear" by The Antlers

- "Life Goes On" Noah and the Whale

- "Album of the Year" by The Good Life

- "Bruce Wayne Campbell Interviewed on the Roof of the Chelsea Hotel, 1979" by Okkervil River

- "Third Week in the Chelsea" by Jefferson Airplane

- "Why Should I Worry?" from Oliver & Company, performed by Billy Joel

- "Chelsea Hotel" by Richard Müller

Books

- Tippins, Sherill (2013). Inside the Dream Palace: the Life and Times of New York's Legendary Chelsea Hotel. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743295617.

- Ramone, Dee Dee. Chelsea Horror Hotel: A Novel. ISBN 1-56025-304-5.

- Vowell, Sarah. Take the Cannoli: Stories From the New World. ISBN 0-7432-0540-5.

- Madonna. Sex. ISBN 0-446-51732-1.

- Hamilton, Ed. Legends of the Chelsea Hotel: Living with the Artists and Outlaws at New York's Rebel Mecca. ISBN 978-1-56858-379-2.

- O'Neill, Joseph. Netherland. ISBN 978-0-307-37704-3.

- Hayter, Sparkle. The Chelsea Girl Murders. ISBN 978-0-14-200010-6.

- Wielaert, Jeroen. Chelsea Hotel, een Biografie van een Hotel (in Dutch). ISBN 90-76927-02-2.

- Smith, Patti. Just Kids. ISBN 978-0-06-093622-8.

- Moody, Hank. God Hates Us All. ISBN 978-1-4165-9823-7.

- Turner, Florence. At The Chelsea. ISBN 978-0151097807.

- Lough, James. This Ain't No Holiday Inn: Down and Out at the Chelsea Hotel 1980–1995. ISBN 1936182521.

- McNeill, Elizabeth. Nine and a Half Weeks: A Memoir of a Love Affair. ISBN 1-56849-171-9.

- Green, Anna, The Heart Rate of a Mouse Volume 2

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Regier, Hilda. "Chelsea Hotel" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995), The Encyclopedia of New York City, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300055366, p.210

- 1 2 3 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S. (text); Postal, Matthew A. (text) (2009), Postal, Matthew A., ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1, p.70

- ↑ Gobrecht, Lawrence E. (April 20, 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Hotel Chelsea". Retrieved February 21, 2010. and Accompanying three photos, exterior, from 1977

- ↑ Rovzar, Chris (July 27, 2013). "Hotel Chelsea No Longer Taking Reservations". New York. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ↑ Miller, Arthur, "The Chelsea Affect", Granta #78: "Bad Company", Summer 2002

- 1 2 3 White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000), AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.), New York: Three Rivers Press, ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5, p.181

- 1 2 3 4 Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X p.151

- ↑ Rich, Nathaniel (October 8, 2013). "Where The Walls Still Talk". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- 1 2 Federal Writers' Project (1939), New York City Guide, New York: Random House, ISBN 0-403-02921-X (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City), p.153

- ↑ Carmin, Craig (May 16, 2011). "Hotel Chelsea's New Proprietor". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ↑ Buckley, Cara (July 31, 2011). "A Last Night Among the Spirits at the Chelsea Hotel". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- 1 2 Kilgannon, Corey. "City Room: First, No More Guests; Now, Chelsea Hotel Says No More Art" The New York Times (November 4, 2011)

- ↑ Prendergast, Daniel; Connor, Tracy (October 22, 2011). "Chelsea Hotel demolition sparks Buildings Dept. probe after complaints from furious residents". New York Daily News.

- ↑ "DOB finds no major violations in Hotel Chelsea renovation" The Real Deal (October 27, 2011)

- ↑ "A New View at Chelsea Hotel" The Wall Street Journal (August 27, 2013)

- ↑ The Real Deal: "King & Grove reneges on Hotel Chelsea eviction vow: Tenants" September 17, 2013

- ↑ http://www.chelseahotels.com/us/new-york/hotel-chelsea/coming-soon

- 1 2 3 4 Chamberlain, Lisa. "Change at the Chelsea, Shelter of the Arts", The New York Times, June 19, 2007. Accessed December 16, 2007. "For six decades the Bard family has managed the Hotel Chelsea, overseeing a bohemian enclave that has been a long-term home for writers, artists and musicians including Mark Twain, O. Henry, Tennessee Williams, Dylan Thomas, Andy Warhol, and Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen."

- 1 2 "10 great places to get on the road and feel the Beat", USA Today, March 10, 2006. Accessed December 16, 2007. "On the West Side, Kerouac and then-wife Joan Haverty lived at 454 W. 20th St., where he began writing her a long letter about his recent travels while she waited tables to support them: The letter became On the Road, "the bible of the Beat generation." He wrote the book itself at the Hotel Chelsea, later the last home of Herbert Huncke."

- ↑ Hamilton, Ed (2007). Legends of the Chelsea Hotel. p. 368. ISBN 1-56858-379-6.

- ↑ "An interview with lesbian Stonewall veteran Stormé DeLarverie". afterellen.com. July 26, 2010.

- ↑ Chelsea Hotel by Carter Tomassi, messyoptics.com

- ↑ July 22, 2010, Le Télégramme,"Little New York stories" exhibition about residence in Chelsea Hotel vs Coney Island, suite 603, author of the paper : Isabelle Nivet

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael. "Alphaeus Cole, a Portraitist, 112", The New York Times, November 26, 1988. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Portrait of Jason: Project Shirley Volume 2". milestonefilms.com/.

- ↑ "One Man, Saved From Invisibility". The New York Times. April 14, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hotel Chelsea. |

- Chelsea Hotel – New York Architecture Images

- 360° Panoramas of Chelsea Hotel before 2011–2012 renovations

- Chelsea's New Proprietor – Wall Street Journal

- "Ed Hamilton: One of the last Chelsea Hotel Bohemians". The Somerville News. January 30, 2013.