Battle of Madagascar

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Madagascar was the British campaign to capture Vichy French-controlled Madagascar during World War II. It began with Operation Ironclad, the seizure of the port of Diego Suarez near the northern tip of the island, on 5 May 1942. A subsequent campaign to secure the entire island, Operation Streamline Jane, was opened on 10 September. Fighting ceased and an armistice was granted on 6 November.[5]

Background

Geopolitical

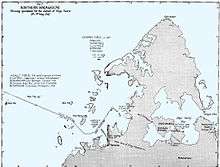

Antsiranana is a large bay with a fine harbour near the northern tip of the island of Madagascar and has an opening to the east through a narrow channel called Oronjia Pass. The naval base of Antsirane lies on a peninsula between two of the four small bays enclosed within the Antsiranana bay. Antsiranana Bay cuts deeply into the northern tip of Madagascar (Cape Amber), almost severing it from the rest of the island.[6] In the 1880s, the bay was coveted by France, which claimed it as a coaling station for steamships travelling to French possessions further east. The colonization was formalized after the first Franco-Hova War when Queen Ranavalona III signed a treaty on 17 December 1885 giving France a protectorate over the bay and surrounding territory, as well as the islands of Nosy Be and St. Marie de Madagascar. The colony's administration was subsumed into that of French Madagascar in 1897.[7]

In 1941, Antsiranana town, the bay and the channel were well protected by naval shore batteries.[6]

Axis

Following the Japanese conquest of South East Asia east of Burma by the end of February 1942, submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy were moving freely throughout the north and eastern expanses of the Indian Ocean. In March 1942, Japanese aircraft carriers conducted the Indian Ocean raid upon shipping in the bay of Bengal and bases in Colombo and Trincomalee in Ceylon. This raid drove the British Eastern Fleet out of the area and they were forced to relocate to a new base at Kilindini, near Mombasa, in Kenya.

The move made the British fleet more vulnerable to attack. The possibility of Japanese naval forces using forward bases in Madagascar had to be addressed. The potential use of these facilities particularly threatened Allied merchant shipping, the supply route to the British Eighth Army and also the Eastern Fleet.

Japanese submarines had the longest range of any Axis forces' subs at the time — more than 10,000 miles (16,000 km) in some cases, but being challenged by the U.S. Navy's then-relatively new Gato-class fleet submarines' 11,000 nautical mile (20,370 km) top range figures. If the IJN's subs were able to utilise bases on Madagascar, Allied lines of communications would be affected across a region stretching from the Pacific and Australia, to the Middle East and as far as the South Atlantic.

On 17 December 1941, Vice Admiral Fricke, Chief of Staff of Germany's Maritime Warfare Command (Seekriegsleitung), met Vice Admiral Naokuni Nomura, the Japanese Naval Attaché, in Berlin to discuss the delimitation of respective operational areas between the Kriegsmarine and Imperial Japanese Navy forces. At another meeting on 27 March 1942, Fricke stressed the importance of the Indian Ocean to the Axis powers and expressed the desire that the Japanese begin operations against the northern Indian Ocean sea routes. Fricke further emphasized that Ceylon, the Seychelles and Madagascar should have a higher priority for the Axis navies than operations against Australia.[8] By 8 April, the Japanese announced to Fricke that they intended to commit four or five submarines and two auxiliary cruisers for operations in the western Indian Ocean between Aden and the Cape, but they refused to disclose their plans for operations against Madagascar and Ceylon, only reiterating their commitment to operations in the area.[9]

Allies

The Allies had heard the rumours of Japanese plans for the Indian Ocean and on 27 November 1941, the British Chiefs of Staff discussed the possibility that the Vichy government might cede the whole of Madagascar to Japan, or alternatively permit the Japanese navy to establish bases on the island. British naval advisors urged the occupation of the island as a precautionary measure.[10] On 16 December, General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French in London, sent a letter to the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, in which he also urged a Free French operation against Madagascar.[11] Churchill recognised the risk of a Japanese-controlled Madagascar to Indian Ocean shipping, particularly to the important sea route to India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and considered the port of Diego Suarez as the strategic key to Japanese influence in the Indian Ocean. However, he also made it clear to planners that he did not feel Britain had the resources to mount such an operation and, following experience in the Battle of Dakar in September 1940, did not want a joint operation launched by British and Free French forces to secure the island.[11]

By 12 March, Churchill had been convinced of the importance of such an operation and the decision was reached that the planning of the invasion of Madagascar would begin in earnest. It was agreed that the Free French would be explicitly excluded from the operation. As a preliminary battle outline, Churchill gave the following guidelines to the planners[12] and the operation was designated Operation Bonus:[13]

- Force H, the ships guarding the Western Mediterranean, should move south from Gibraltar and should be replaced by an American Task Force

- The 4,000 men and ships proposed by Lord Mountbatten for the operation, should be retained as the nucleus around which the plan should be built

- The operation should commence around 30 April 1942

- In the event of success, the commandos recommended by Mountbatten should be replaced by Garrison Troops as soon as possible[12]

On 14 March, "Force 121" was constituted under the command of Major-General Robert Sturges of the Royal Marines with Rear-Admiral Edward Syfret being placed in command of Naval Force H and the supporting sea force.[14]

Allied preparations

Force 121 left the Clyde in Scotland on 23 March and joined up with South African-born Admiral Syfret's ships at Freetown in Sierra Leone, proceeding from there in two convoys to their assembly point at Durban on the South African east coast. Here they were joined by the 13th Brigade Group of the 5th Division – General Sturges' force consisting of three infantry brigades, while Admiral Syfret's squadron consisted of the flag battleship HMS Ramillies, the aircraft carriers HMS Illustrious and HMS Indomitable, the cruisers HMS Hermione and HMS Devonshire, eleven destroyers, six minesweepers, six corvettes and auxiliaries. It was a formidable force to bring against the 8,000 men (mostly Malagasy) at Diego Suarez, but the Chiefs of Staff were adamant that the operation was to succeed, preferably without any fighting.[14]

This was to be the first British amphibious assault since the disastrous landings in the Dardanelles twenty-seven years before.[15]

During the assembly in Durban, Field-Marshal Jan Smuts pointed out that the mere seizure of Diego Suarez would be no guarantee against continuing Japanese aggression and urged that the ports of Majunga and Tamatave be occupied as well. This was evaluated by the Chiefs of Staff, but it was decided to retain Diego Suarez as the only objective due to the lack of manpower.[14] Churchill remarked that the only way to permanently secure Madagascar was by means of a strong fleet and adequate air support operating from Ceylon and sent General Archibald Wavell (India Command), a note stating that as soon as the initial objectives had been met, all responsibility for safeguarding Madagascar would be passed on to Wavell. He added that when the Commandos were withdrawn, garrison duties would be performed by two African brigades and one brigade from the Belgian Congo or west coast of Africa.[16]

In March and April, the South African Air Force (SAAF) had conducted reconnaissance flights over Diego Suarez and No. 32, 36 and 37 Coastal Flights were withdrawn from maritime patrol operations and sent to Lindi on the Indian Ocean coast of Tanganyika, with an additional eleven Bristol Beauforts and six Martin Marylands to provide close air support during the planned operations.[6]

Campaign

Allied commanders decided to launch an amphibious assault on Madagascar. The task was Operation Ironclad and executed by Force 121; it would comprise allied naval, land and air forces and be commanded by Major-General Robert Sturges of the Royal Marines. The British Army landing force comprised 29th Independent Infantry Brigade Group, No 5 (Army) Commando and two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division, the latter en route to India with the remainder of their division. The Allied naval contingent consisted of over 50 vessels, drawn from Force H, the British Home Fleet and the British Eastern Fleet, commanded by Rear Admiral Edward Neville Syfret. The fleet included the aircraft carrier Illustrious, her sister ship Indomitable and the aging battleship Ramillies to cover the landings.

Landings (Operation Ironclad)

Following many reconnaissance missions by the SAAF, the first wave of the British 29th Infantry Brigade and No. 5 Commando landed in assault craft on 5 May 1942, follow-up waves were by two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division and Royal Marines. All were carried ashore by landing craft to Courrier Bay and Ambararata Bay, just west of the major port of Diego Suarez (later known as Antsiranana), at the northern tip of Madagascar. A diversionary attack was staged to the east. Air cover was provided mainly by Fairey Albacore and Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers which attacked Vichy shipping. They were supported by Grumman Martlets (known by the Americans as the F4F Wildcat) fighters from the Fleet Air Arm. A small number of SAAF planes assisted.

The defending Vichy forces, led by Governor General Armand Léon Annet, included about 8,000 troops, of whom about 6,000 were Malagasy tirailleurs (colonial infantry). A large proportion of the rest were Senegalese. Between 1,500 and 3,000 Vichy troops were concentrated around Diego Suarez. However, naval and air defences were relatively light and/or obsolete: eight coastal batteries, two armed merchant cruisers, two sloops, five submarines, 17 Morane-Saulnier 406 fighters and 10 Potez 63 bombers.

The French defence was highly effective in the beginning and the main Allied force was brought to a halt by the morning of 6 May. The deadlock was broken when the old destroyer HMS Anthony dashed straight past the harbour defences of Diego Suarez and landed 50 Royal Marines amidst the Vichy rear area. The Marines created "disturbance in the town out of all proportion to their numbers" and the Vichy defence was soon broken. Diego Suarez was surrendered on 7 May, although substantial Vichy forces withdrew to the south.[17]

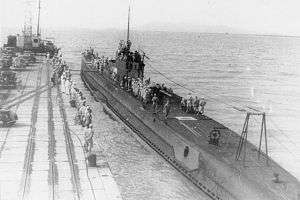

The Japanese submarines I-10, I-16 and I-20 arrived three weeks later on 29 May. I-10's reconnaissance plane spotted HMS Ramillies at anchor in Diego Suarez harbour but the plane was spotted and Ramillies changed her berth. I-20 and I-16 launched two midget submarines, one of which managed to enter the harbour and fired two torpedoes while under depth charge attack from two corvettes. One torpedo seriously damaged Ramillies, while the second sank the 6,993 ton oil tanker British Loyalty (later refloated). Ramillies was later repaired in Durban and Plymouth.

The crew of one of the midget submarines, Lieutenant Saburo Akieda and Petty Officer Masami Takemoto, beached their craft (M-20b) at Nosy Antalikely and moved inland towards their pick-up point near Cape Amber. They were informed-upon when they bought food at the village of Anijabe and both were killed in a firefight with Royal Marines three days later; one Marine was killed in the action as well. The second midget submarine was lost at sea and the body of one of its crew was found washed ashore a day later.

Ground campaign (Operation Streamline Jane)

Hostilities continued at a low level for several months. After 19 May two brigades of the 5th Infantry Division were transferred to India. On 8 June, the 22nd (East Africa) Brigade Group arrived on Madagascar[18] The 7th South African Motorized Brigade arrived on 24 June.[19] The 27th (North Rhodesia) Infantry Brigade (including forces from East Africa) landed on 8 August.[20]

On 10 September the 29th Brigade and 22nd Brigade Group made an amphibious landing at Majunga, in the northwest, to re-launch Allied offensive operations ahead of the rainy season. Progress was slow for the Allied forces though. In addition to occasional small-scale clashes with enemy forces, they also encountered scores of obstacles erected on the main roads by Vichy soldiers. The Allies eventually captured the capital, Tananarive, without much opposition, and then the town of Ambalavao. The last major action was at Andramanalina on 18 October. An armistice was signed in Ambalavao on 6 November, and Annet surrendered near Ihosy, in the south of the island, on 8 November 1942.[21]

The Allies suffered about 500 casualties in the landing at Diego Suarez, and 30 more killed and 90 wounded in the operations which followed on 10 September.

Aftermath

Free French General Paul Legentilhomme was appointed High Commissioner for Madagascar. Like many colonies, Madagascar sought its independence following the war. In 1947, the island experienced the Malagasy Uprising, a costly revolution that was crushed in 1948. It was not until 26 June 1960, about twelve years later, that the Malagasy Republic successfully proclaimed its independence from France.

Campaign service in Madagascar did not qualify for the British and Commonwealth Africa Star. It was instead covered by the 1939–1945 Star.[22]

Order of battle

Allied Forces

Naval forces

- Battleships

- HMS Ramillies

- HMS Warspite

- Aircraft Carriers

- HMS Illustrious

- HMS Indomitable

- Cruisers

- HMS Birmingham[23]

- HMS Dauntless[23]

- HMS Gambia[23]

- HMS Hermione

- HMS Devonshire

- HNLMS Jacob van Heemskerck

- Minelayer

- HMS Manxman[23]

- Monitor

- HMS Erebus[23]

- Seaplane Carrier

- HMS Albatross[23]

- Destroyers

- HMS Active

- HMS Anthony

- HMS Arrow[23]

- HMS Blackmore[23]

- HMS Duncan

- HMS Fortune[23]

- HMS Foxhound[23]

- HMS Inconstant

- HMS Hotspur[23]

- HMS Javelin

- HMS Laforey

- HMS Lightning

- HMS Lookout

- HMAS Napier[23]

- HMAS Nepal[23]

- HMAS Nizam

- HMAS Norman

- HMS Pakenham

- HMS Paladin

- HMS Panther

- HNLMS Van Galen[23]

- HNLMS Tjerk Hiddes[23]

- Corvettes

- HMS Freesia

- HMS Auricula

- HMS Nigella

- HMS Fritillary

- HMS Genista

- HMS Cyclamen

- HMS Thyme

- HMS Jasmine

- Minesweepers

- HMS Cromer

- HMS Poole

- HMS Romney

- HMS Cromarty

- Assault transports

- HMS Winchester Castle

- HMS Royal Ulsterman

- HMS Keren

- HMS Karanja

- MS Sobieski (Polish)

- Special ships

- HMS Derwentdale (LCA)

- HMS Bachaquero (LST)

- Troop ships...

- SS Oronsay

- SS Duchess of Atholl

- RMS Franconia

- Stores and MT ships

- SS Empire Kingsley

- M/S Thalatta

- SS Mahout

- SS City of Hong Kong

- SS Mairnbank

- SS Martand II[24]

Ground forces

- 29th Infantry Brigade (independent) arrived via amphibious landing near Diego Suarez on 5 May 1942

- 2nd South Lancashire Regiment

- 2nd East Lancashire Regiment

- 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers

- 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers

- 455th Light Battery (Royal Artillery)

- MG company

- 'B' Special Service Squadron with 6 Valentine and 6 Tetrarch tanks

- Commandos arrived via amphibious landing near Diego Suarez on 5 May 1942

- No. 5 Commando

- British 17th Infantry Brigade Group (of 5th Division) landed near Diego Suarez as second wave on 5 May 1942

- 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers

- 2nd Northamptonshire Regiment

- 6th Seaforth Highlanders

- 9th Field Regiment (Royal Artillery)

- British 13th Infantry Brigade (of 5th Division) landed near Diego Suarez as third wave on 6 May 1942. Departed 19 May 1942 for India

- 2nd Cameronians

- 2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers

- 2nd Wiltshire Regiment

- East African Brigade Group arrived 22 June to replace 13 and 17 Brigades

- South African 7th Motorised Brigade

- Rhodesian 27th Infantry Brigade arrived 8 August 1942; departed 29 June 1944

- 2nd Northern Rhodesia Regiment

- 3rd Northern Rhodesia Regiment

- 4th Northern Rhodesia Regiment

- 55th (Tanganyika) Light Battery

- 57th (East African) Field Battery[24]

Fleet Air Arm

- Aboard HMS Illustrious

- 881 Squadron - 12 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat (Martlet Mk.II)

- 882 Squadron - 8 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat (Martlet Mk.II) 1 Fairey Fulmar

- 810 Squadron - 10 Fairey Swordfish

- 829 Squadron - 10 Fairey Swordfish

- Aboard HMS Indomitable

- 800 Squadron - 8 Fairey Fulmar

- 806 Squadron - 4 Fairey Fulmar

- 880 Squadron - 6 Hawker Sea Hurricane Mk IA

- 827 Squadron - 12 Fairey Albacore

- 831 Squadron - 12 Fairey Albacore[24]

Vichy France

Naval Forces

- Merchant Cruiser Bougainville 2

- Sloop D'Entrecasteaux

- Submarines

- Bévéziers

- Héros

- Monge[24]

Land forces

The following order of battle represents the Malagasy and Vichy French forces on the island directly after the initial Ironclad landings.[27]

.jpg)

- West coast

- Two platoons of reservists and volunteers at Nossi-Bé

- Two companies of the Régiment Mixte Malgache (RMM – Mixed Madagascar Regiment) at Ambanja

- One battalion of the 1er RMM at Majunga

- East coast

- One battalion of the 1er RMM at Tamatave

- One artillery section (65mm) at Tamatave

- One company of the 1er RMM at Brickaville

- Centre of the island

- Three battalions of the 1er RMM at Tananarive

- One motorised reconnaissance detachment at Tananarive

- Emyrne battery at Tananarive

- One artillery section (65mm) at Tananarive

- One engineer company at Tananarive

- One company of the 1er RMM at Mevatanana

- One company of the BTM at Fianarantsoa

- South of the island

- Other

- One company of the BTM at Fort Dauphin

- One company of the BTM at Tuléar

Japan

Naval forces

- Submarines I-10 (with reconnaissance aircraft), I-16, I-18 (damaged by heavy seas and arrived late), I-20

- Midget submarines M-16b, M-20b

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Blyfield, Judith A.; Brown, Carolyn A.; Parsons, Timothy; Sikainga, Ahmad Alawad (2015), "1: The Military Experiences of Ordinary Africans in World War II", Africa and World War II, Cambridge University Press, p. 71, ISBN 9781107630222

- 1 2 3 Wessels 1996.

- ↑ Stapleton, Timothy J. A Military History of Africa p. 225

- ↑ Winston Churchill, Prime Minister (10 November 1942). http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1942/nov/10/madagascar-operations#column_2259

|chapter-url=missing title (help). Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. - ↑ Thomas 1996.

- 1 2 3 Turner 1961, p. 133.

- ↑ "History of Madagascar". History World. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ↑ Turner 1961, p. 116.

- ↑ Turner 1961, p. 117.

- ↑ Turner 1961, p. 131.

- 1 2 Churchill 1950, p. 223.

- 1 2 Churchill 1950, p. 225.

- ↑ Churchill 1950, p. 229.

- 1 2 3 Turner 1961, p. 132.

- ↑ Churchill 1950, p. 230.

- ↑ Churchill 1950, p. 231.

- ↑ Combined Operations: the Official Story of the Commandos. Great Britain: Combined Operations Command. 1943. pp. 101–109. ISBN 9781417987412.

- ↑ Joslen 2003, pp. 421–422.

- ↑ http://books.stonebooks.com/armies/unit/SA110/

- ↑ Joslen 2003, pp. 425–426.

- ↑ "World Battlefronts: Madagascar Surrenders". Time Magazine. November 16, 1942.

- ↑ "Medals: campaigns, descriptions & eligibility", Guidance, UK: Government.

- 1 2 3 4 "Operation Ironclad: Invasion of Madagascar". Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ↑ Nafziger, George. "Operation Ironclad Invasion of Madagascar 5 May 1942" (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Research Library. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ Nafziger, George. "British Infantry Brigades 1st thru 215th 1939-1945" (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Research Library. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ "Madagascar, Ordres de bataille" (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2013.

References

- Churchill, Winston (1950). The Hinge of Fate. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 396148.

- Joslen, H.F. (2003). Orders of Battle, United Kingdom and Colonial Formations and Units in the Second World War, 1939–1945. I. London; Uckfield: HM Stationery Office; Naval & Military. ISBN 1843424746.

- Thomas, Martin (December 1996). "Imperial Backwater or Strategic Outpost? The British Takeover of Vichy Madagascar, 1942". The Historical Journal. Cambridge University Press. 39 (4): 1049–74. doi:10.1017/s0018246x00024754. JSTOR 2639867.

- Turner, Leonard Charles Frederick; Gordon-Cummings, H.R; Betzler, J.E. (1961). Turner, L.C.F., ed. War in the Southern Oceans: 1939–1945. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. OCLC 42990496. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Wessels, André (June 1996). "South Africa and the War against Japan, 1941–1945". Military History Journal. South African Military History Society. 10 (3).

- Jennings, Eric T. (2001). Vichy in the Tropics: Petain's National Revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe, and Indochina, 1940-44. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804750475.

Further reading

- Harrison, E.D.R. (April 1999). "British Subversion in French East Africa, 1941–42: SOE's Todd Mission". English Historical Review. 114 (456): 339–369. doi:10.2307/580082. JSTOR 580082.

- Nativel, Eric (1998). "La "guérilla" des troupes vichystes à Madasgar en 1942". Revue Historique des Armées. 1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Ironclad. |

- exordio.com, ?, "Operación Ironclad" (Spanish language)

- Outline of Japanese involvement

- BBC History Magazine podcast about the Battle of Madagascar