Neveryóna

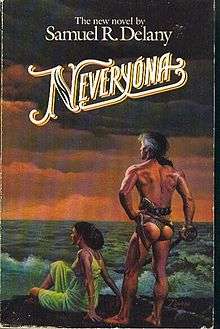

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Samuel R. Delany |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Rowena Morrill |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Return to Nevèrÿon |

| Genre | Sword and Sorcery |

| Publisher | Bantam Books |

Publication date | 1983 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 385 pp |

| ISBN | 0-553-01434-X |

| OCLC | 9969945 |

| 813/.54 19 | |

| LC Class | PS3554.E437 N4 1983 |

| Preceded by | Tales of Nevèrÿon |

| Followed by | Flight from Nevèrÿon |

Neveryóna, or: The Tale of Signs and Cities is a sword and sorcery novel by Samuel R. Delany. It is the second of the four-volume Return to Nevèrÿon series. This article discusses the novel itself. Discussions of overall plot, setting, characters, themes, structure, and style of the series are found in the main series article.

Plot summary

Neveryóna (a full-length novel), the sixth and longest tale of the Return to Nevèrÿon series, focuses on fifteen-year-old Pryn, who is extraordinary in this culture because she can read and write. Pryn is the great niece of an unsung genius of Nevèrÿon, a woman who invented both the loom and the spindle. Because she did not have the good fortune also to discover that wool made the best and strongest cloth, however, all the credit for her work tends to be given to other people. Pryn’s travels take her (and the reader) not only to explore the revolutionary forces of Gorgik’s campaign—and some of its internal squabbles—but also through the homes of several wealthy conservatives. In the first half of the novel, Pryn finds herself in Neveryóna, an upper class suburb of Port Kolhari, an uneasy guest in the emotionally embattled gardens of a wealthy merchant woman, Madame Keyne, whom we first met in the third story, “The Tale of Potters and Dragons,” and who is now actively financing a crackpot group of counter rebels who want to put an end to Gorgik’s project. In the second half, once Pryn travels into the south, she is taken up by the powerful Jue Gruten family, who represent the far more lethal and aristocratic forces of the nation who want to end this rebellion. Here the webs of power are almost too complex and wide reaching for Pryn to comprehend, even though she now realizes that one can fight them, a single incident at a time, as she manages to free a single slave from their grip, whom the Earl has tried to use as a scapegoat. But Pryn and the reader now have a far clearer picture of what Gorgik is up against.

Between the novel’s first part and its second part, Pryn spends some time with a good-hearted but sadly limited peasant family, who live in the little town of Enoch and who represent the working classes that Gorgik will have to enlist somehow if he is to succeed. (A city name that appears several times throughout Delany’s non-Nevèrÿon work, notably in The Mad Man [1994], "Enoch" is mentioned in Genesis as the first city built by man, specifically by Cain’s son, Adam and Eve’s grandson, after whom it was named. In Delany's work, “Enoch” is never a big city. Rather it is a very old and small city—often much older than it thinks it is—which has forgotten its own historical origins.) These are the people who have the least sense of their own history. Their perfectly sensible wants conspire, nevertheless, to defeat their own best interests, and the only role they can conceive of in which Pryn can stay among them is that of the town prostitute. It is the most devastating section of the novel.

An added irony is that this section is written using all the characters from that central myth of romanticism, “Tristan and Isolde” (with Pryn playing the part of Isolde), employing elements from many of the versions, including the story of “Tristan’s Leap,” and the tales of Malot, King Mark, and Bragenge from Wagner, and even the dwarf Frocsin, from Jean Cocteau’s film version from the forties, “The Eternal Return” (1943). In Delany’s version, apathy and despair have replaced passion and romance. Only the power of Pryn’s own imagination gives her a weapon to fight free from the seductions of these simple people’s basic goodness and her own ensnarement in their fundamental hopelessness.

References

- "The Internet Speculative Fiction Database". Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Brown, Charles N.; William G. Contento. "The Locus Index to Science Fiction (1984-1998)". Retrieved 2008-01-02.

Further reading

- Tucker, Jeffery A. A Sense of Wonder: Samuel R. Delany, Race, Identity and Difference, chapter 3: "The Empire of Signs: Slavery, Semiotics, and Sexuality in the Return to Nevèrÿon Series". Wesleyan University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8195-6689-6