Military history of Myanmar

| History of Myanmar |

|---|

_peacock.svg.png) |

|

|

|

|

The military history of Myanmar (Burma) spans over a millennium, and is one of the main factors that have shaped the history of the country, and to a lesser degree the histories of the country's neighbours. At various times in history, successive Burmese kingdoms were also involved in warfare against their neighbouring states in the surrounding regions of modern Burmese borders—from Bengal, Manipur and Assam in the west, to Yunnan (the southern China) in the northeast, to Laos and Siam in the east and southeast.

The Royal Burmese Army was a major Southeast Asian armed force between the 11th and 13th centuries and between 16th and 19th centuries. It was the premier military force in the 16th century when Toungoo kings built the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia.[1] The centuries-long warfare between Burma and Siam (1547–1855) shaped not only the history of both countries but also that of mainland Southeast Asia. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, highly militaristic Konbaung kings had built the largest empire in mainland Southeast Asia until they ran into the British in present-day northeast India.[2][3] Prior to the three Anglo-Burmese wars (1824–1885), previous existential threats to the country had come from China in the form of Mongol invasions (1277–1301) and Manchu invasions (1765–1769).

The country was a major battle front in the Southeast Asian theatre of World War II. Since independence in 1948, the country's various political and ethnic factions have been locked in one of the longest civil wars today, with myriad insurgencies receiving implicit and explicit help from various external states.[4]

Early history

The military history in the early era is sketchy. The Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu, the earliest inhabitants of the Irrawaddy valley in recorded history, founded several city states that thrived between the 1st century BCE and the early 9th century CE. Eighth-century Chinese records identify 18 Pyu states throughout the Irrawadddy valley, and describe the Pyu as a humane and peaceful people to whom war was virtually unknown and who wore silk cotton instead of actually silk so that they would not have to kill silk worms.[5] To be sure, this peaceful description by the Chinese was a snapshot of the Pyu realm, and may not represent the life in the city-states in general.

The earliest extant record of warfare in the Pyu realm is the early 9th century when the Pyu states came under constant attacks by the armies of the Kingdom of Nanzhao (from present-day Yunnan). Nanzhao had just become a major military power in the region by defeating the Tibetan Empire in 801. The Nanzhao warriors then pressed down southward into the present-day Shan Hills and into the Irrawaddy valley. Ancient city-states one by one surrendered or were overrun by the "powerful mounted archers from the north". In 832, Nanzhao destroyed the city-state of Halin, close to old Tagaung, returning again in 835 to carry off many captives. The Nanzhao cavalry is said to have swept down all the way to the Bay of Bengal despite stiff resistance.[6]

Pagan period

Following the Nanzhao raids, another Tibeto-Burman-speaking people called the Mranma (Burmans or Bamar), who had come down with the Nanzhao raids, began to settle the central Irrawaddy valley, near the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers, en masse. The Burmans founded a small fortified city of Pagan (Bagan) c. 849, probably to help the Nanzhao pacify the surrounding country side.[7] The early Pagan army consisted mainly of conscripts raised just prior to or during the times of war. The main weaponry of the infantry largely consisted of swords, spears and bow and arrows. The infantry units were supported by cavalry and elephantry corps. The Pagan army would later be known to the world for their war elephants as reported by Marco Polo.

Pagan Empire

By King Anawrahta's accession in 1044, the small principality had gradually grown to include its immediate surrounding area—to about 200 miles north to south and 80 miles from east to west.[8] Over the next 30 years, Anawrahta went on to unify for the first time the regions that would later constitute the modern-day Burma. Anawrahta began his campaigns in the nearer Shan Hills, and extended conquests to Lower Burma down to the Tenasserim coast to Phuket and North Arakan.[7] Anawrahta's conquest of Tenasserim checked the Khmer Empire's encroachment in the Tenasserim coast, and secured control of the peninsula ports, which were transit points between the Indian Ocean and China.[9]

After a flurry of military campaigns by Anawrahta, Pagan entered a gilded age that would last for the next two centuries. Aside from a few occasional rebellions, the kingdom was largely peaceful during the period. The most serious was the 1082–1084 rebellion by Pegu (Bago), which nearly toppled the Pagan regime. In the 1110s, Pagan sent two separate expeditions to Arakan to place its claimant Letya Min Nan on the Arakanese throne. The first expedition failed but the second in 1118 succeeded.[10] Sinhalese Mahavamsa Chronicles mention a dispute over trade in elephants between Burma and Sri Lanka that prompted the Ceylonese forces to raid Lower Burma in 1180.[9][11]

The authority of Pagan continued to grow, peaking in the reign of King Narapatisithu (r. 1174–1211). The king formally founded the Royal Palace Guards in 1174, the first extant record of a standing army. Pagan's influence reached further south into the upper Malay peninsula, at least to the Salween river in the east, below the current China border in the farther north, and to the west, northern Arakan and the Chin Hills.[12] Up to the first half of the 13th century, much of mainland Southeast Asia was under some degree of control of either the Pagan Empire or the Khmer Empire.

Late 13th century rebellions

The Pagan military power was closely intertwined with the kingdom's economic prowess. The kingdom went into decline in the 13th century as the continuous growth of tax-free religious wealth—by the 1280s, two-thirds of Upper Burma's cultivable land had been alienated to the religion—affected the crown's ability to retain the loyalty of courtiers and military servicemen. This ushered in a vicious circle of internal disorders and external challenges by Mons, Mongols and Shans.[13]

The first signs of disorder appeared soon after Narathihapate's accession in 1256. The inexperienced king faced revolts in Arakanese state of Macchagiri (present-day Kyaukpyu District)[14] in the west, and Martaban (Mottama) in the south. The Martaban rebellion was easily put down but Macchagiri required a second expedition before it too was put down.[15] The calm did not last long. Martaban again revolted in 1281.

Mongol invasions

.png)

This time, Pagan could not do anything to retake Martaban because it was facing an existential threat from the north. The Mongols demanded tribute, in 1271 and again in 1273. When Narathihapate refused both times, the Mongols systematically invaded the country. The first invasion in 1277 defeated the Burmese at the battle of Ngasaunggyan, and secured their hold of Kanngai (modern-day Yingjiang, Yunnan, 112 km north of Bhamo). In 1283–1285, their forces moved south and occupied down to Tagaung and Hanlin. The king fled to Lower Burma in 1285 before agreeing to submit to the Mongols in June 1286.[16][17] Soon after the agreement was finalised, the king was assassinated in July 1287. The Mongols once again invaded south toward Pagan.[17]

Recent research indicates that Mongol armies may not have reached Pagan itself, and that even if they did, the damage they inflicted was probably minimal.[18] But the damage was already done. All the vassal states of Pagan revolted right after the king's death, and went their own way. In the south, Wareru, the man who had seized the governorship of Martaban in 1281, consolidated Mon-speaking regions of Lower Burma, and declared Ramannadesa (Land of the Mon) independent. In the west too, Arakan stopped paying tribute.[19] The 250-year-old Pagan Empire had ceased to exist.

Warring states period

The political vacuum created by the sudden collapse of Pagan triggered constant warfare that would engulf the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery for the next 350 years. In retrospect, the two centuries of peace and order maintained by the Pagan Empire turned out to be rather remarkable. The main cause for warfare was that no strong polity emerged to reunite the kingdom. After their 1287 invasion, the Mongols moved farther south to Tagaung but refused to fill in the power vacuum they had created. Indeed, Emperor Kublai Khan never sanctioned an actual occupation of Pagan.[19] His real aim appeared to have been "to keep the entire region of Southeast Asia broken and fragmented."[20]

Last Mongol invasion

At Pagan, the new king Kyawswa controlled just a small area outside the capital. Instead, the real power rested with three former Pagan commanders of nearby Myinsaing. It was the brothers, not the nominal sovereign Kyawswa, that sent a force to retake Lower Burma in 1294 after Wareru had decided to become a vassal of the Sukhothai Kingdom. Wareru drove back the Myinsaing forces.[21]

Concerned by the increasing power of the three brothers, Kyawswa submitted to the Mongols in January 1297, and was recognised by the Mongol emperor Temür Khan as viceroy of Pagan on 20 March 1297. In December 1297, the three brothers overthrew Kyawswa, and founded the Myinsaing Kingdom. In January 1300, the Myinsaing forces led by Athinhkaya seized the southernmost Mongol garrisons named Nga Singu and Male, just north of modern Mandalay. On 22 June 1300, the Mongol Emperor declared that Kumara Kassapa, one of Kyawswa's sons, was the rightful king of Burma, and sent in a 12,000-strong army from Yunnan. The Mongol army reached Male on 15 January 1301, and Myinsaing on 25 January. But they could not break through. The besiegers took the bribes given by the three brothers, and began their retreat on 6 April. But the commanders were executed by the Yunnan government when they got back.[22] The Mongols sent no more invasions, and withdrew entirely from Upper Burma on 4 April 1303.[23][24]

First Shan raids

The Mongols left but the Shan people, who had come down with the Mongols did not—just as the Burmans who came down with the Nanzhao invasions stayed behind four centuries earlier. The Shans built an array of small states in the entire northwestern to eastern arc of central Burma, thoroughly surrounding the valley. They continued to raid the Irrawaddy valley throughout the 14th century, taking advantage of the split of Myinsaing into Pinya and Sagaing kingdoms in 1315. Starting in 1359, then the most powerful Shan state of Mogaung (in present-day Kachin State) began a series of sustained assaults on central Burma. In 1364, its forces sacked both Sagaing and Pinya in succession, and left off with the loot.

The power vacuum did not last long. In the same year, Thado Minbya, a Sagaing prince, emerged to reunify Upper Burma and founded the Ava Kingdom. Nonetheless, Shan raids into Upper Burma continued off-and-on in spurts. The raids were led by different Shan states at different times. Mogaung's devastating raids (1359–1368) were replaced in the 1370s and 1390s by Mohnyin's raids that reached as far south as Sagaing. After Ava conquered Mohnyin in 1406, the mantle was picked up by Theinni (Hsweni) which raided Avan territory from 1408 to 1413.

The intensity and frequency of the raids lessened in the 15th century due to both the rise of Ava and indeed the arrival of the Ming Chinese in Yunnan in the 1380–1388.[25]

Chinese expeditions against Shan states

Though hemmed in by two powerful kingdoms, the Shan states were able to create a space for themselves for another century and a half, ironically by using state-of-the-art Chinese military technology. Chinese firearms reached northern mainland Southeast Asia by way of Chinese traders and renegade soldiers, who despite the Ming government's prohibition, actively smuggled primitive handguns, gunpowder, cannon and rockets. True metal barrelled handguns, first developed in 1288, and metal barrelled artillery from the first half of the 14th century had also spread. The Shans soon learned to replicate Chinese arms and military techniques, and were able to strengthen their position not only against Ava but also against Ming China itself.[26][27]

Attempts to impose order in the unruly Shan states proved difficult even for the Chinese. The Ming government's four campaigns (1438–1449) failed to achieve any lasting order. The Chinese troops fruitlessly chased Shan rebels, who simply returned when the Chinese troops left. The Chinese even chased the Shan rebels into Burmese territory, and left only after the Burmese gave up the dead body of the chief. (The event took place in either 1445–1446 according to the Burmese chronicles or 1448–1449, according to the Chinese records.)[28][29] Faced with more pressing rebellions elsewhere, the Ming government gave up trying to impose imperial order in the Yunnan borderlands, and had to be content with receiving nominal tribute.[28] The Shan states would maintain their space until the mid-16th century.

Hanthawaddy–Sukhothai

In the south too, the Mon-speaking kingdom based out of Martaban had slowly come into its own. It formally broke away from its overlord Sukhothai in 1330. The southern kingdom's relationship with Sukhothai had always been an opportunistic arrangement from the beginning, designed to secure its rear in case of invasions from Upper Burma. In March 1298, just four years after he became a vassal of Sukhothai, when the Upper Burma ceased to be a threat, Wareru conveniently asked for and received recognition directly from the Mongol emperor as governor even though Sukhothai itself was already a vassal of the Mongols.[23] Indeed, when Sukhothai grew weaker, Martaban seized the Tenasserim coast from Sukhothai in 1319. A decade later, Sukhothai tried to reassert control, reoccupying Tenasserim, and attacking Martaban in 1330. Martaban's defences held. It threw off any formal ties with Sukhothai.

Nonetheless, the kingdom remained fragmented into three power centres: the Irrawaddy delta in the west, Pegu in the middle and Martaban in the southeast, each with its own chief, who pledged nominal allegiance to the high king. In 1363, Martaban revolted, and outlasted Pegu's armies. After six years, Pegu gave up. Martaban would be independent for another 20 years until 1389.

Forty Years' War

Ava's first kings believed that Ava was the rightful successor to Pagan, and would try to restore the empire. In the south, in 1366, it defeated Toungoo, which had been independent (from Pinya) since 1347. In the northwest, the Shan state of Kale (Kalay) became a tributary in 1371. In the west, Ava's candidate to Arakan's throne became king in 1374. In 1385, Ava looked south where the throne of Hanthawaddy Pegu had just been filled by a 16-year-old Razadarit, and launched a war that would go on for another 40 years.

Razadarit proved quite able, however, to meet Ava's challenge. By 1391, he had not only repelled Ava's invasions but also recaptured Martaban which had been in revolt since 1363. Ava and Pegu entered into a truce in 1391. But in the early 15th century when Ava's new king Minkhaung I was facing multiple rebellions, Razadarit invaded the upcountry with a large naval force. But Ava's defences held, and the two sides reached another truce in early 1406.

After the second truce with Pegu, Ava resumed its acquisition spree elsewhere. By late 1406, its armies had taken Arakan in the west and Mohnyin in the north. It proved too much for Pegu as it could not get Ava to get too strong. Razadarit again broke the truce in late 1407 by driving out Ava's garrison in Arakan. He also got the Shan state of Theinni (Hswenwi) to attack Ava from the north. Ava fought off attacks from both sides, and by 1410, under the leadership of Crown Prince Minye Kyawswa, began to gain an upper hand. Minye Kyawswa decisively defeated Theinni and its Chinese troops in 1413. With the rear secure, the prince invaded the Hanthawaddy country in full force in 1414. He was on the cusp of victory when he was killed in action in 1415. The war lost steam after Minye Kyawswa's death, and ended soon after both Minkhaung and Razadarit died in 1422.

Rise of Mrauk-U

Another key development in the wake of the Forty Years' War was the emergence of a unified and powerful Arakan. The western littoral between the Arakan Yoma and the Bay of Bengal remained politically fragmented even after Pagan's fall. The coast was divided between at least two power centres at Launggyet in the north and Sandoway (Thandwe) in the south. The weakness became exposed between 1373 and 1429 when the region was first subject first to Avan and then to Peguan interference.[30] Arakan was Pegu's vassal from 1412 at least until Razadarit's death in 1421.

The restoration came in 1429 when the last king of Arakan, Saw Mon III, in exile since 1406, came back with an army provided by Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah of Bengal. Narameikhla again became king, though as a vassal of Bengal. The vassalage was brief. In 1437, Saw Mon's brother Khayi annexed Sandoway and Ramu, his overlord's territory, unifying the Arakan littoral for the first time in history.[31] An ascendant Arakan seized Chittagong in 1459, and received tribute from the Ganges delta.[32]

Ava's internal rebellions

_Myanmar(Burma).jpg)

After the end of Forty Years' War in 1424, Ava gave up its dream of rebuilding the Pagan Empire. Instead, for the next six decades, it would struggle to hold on to its vassal states. Rebellions arose every time a new king came to power. The new king would have to reestablish his power all over again by gaining the fealty of all the vassal states, usually by show of force. Of these, the remote vassal state of Toungoo (Taungoo), tucked away in the southeastern corner across the Pegu Yoma range, proved most troublesome to successive kings at Ava. Toungoo lords rebelled against Ava in 1426–1440, 1451–1459 and 1468–1470, usually with Pegu's implicit or explicit support.[33] Ava also faced rebellions at Mohnyin (1450) and Prome (1469).

The beginning of the end of Ava came in 1480. The new king Minkhaung II was greeted with a multitude of rebellions but it proved to be different this time. The most serious rebellion was by his younger brother, lord of Yamethin. With a serious rebellion so close to Ava, vassal states broke away one by one. The Yamethin rebellion went on until 1500. In 1482, Minkhaung's uncle at Prome successfully revolted, the Prome Kingdom sprang into existence. Ava's vassal Shan states of Mohnyin, Mogaung, Momeik and Kale also broke away in the 1490s. Surprisingly, Ava's steadfast ally during this period was the usually restive vassal of Toungoo which remained loyal to Ava until Minkhaung's death in 1501.

Second Shan raids

Ava's authority deteriorated further in Shwenankyawshin's reign (1501–1527). Three of the king's own brothers openly raised a rebellion in 1501. Mohnyin, Ava's former vassal, now began to raid its territory. In 1507, Ava ceded to Mohnyin all northern Avan territory down to present-day Shwebo in the vain hope that the raids would stop. It did not. Ava desperately tried to retain Toungoo's loyalty by ceding the key Kyaukse granary to Toungoo but it too failed. Toungoo took the region but formally broke away in 1510.

Ava's only ally was the Shan state of Thibaw (Hsipaw), which too was fighting Mohnyin's raids on its territory. Mohnyin was attacking other Shan states when it was not raiding Ava. It seized Bhamo from Thibaw in 1512 in the east, and raiding Kale in the west. The Ava-Thibaw alliance was able to retake Shwebo for a time but Mohnyin proved too strong. By the early 1520s, Chief Sawlon of Mohnyin had assembled a confederation of Shan states (Mogaung, Bhamo, Momeik, and Kale) under his leadership. Prome had also joined the confederation. The confederation wiped out Ava's defences in Shwebo in 1524. Finally on 25 March 1527, the forces of the confederation and Prome took Ava.[34]

The Confederation later sacked Prome in 1533 because Sawlon felt that Prome had not given sufficient help.[35]

Toungoo period

Toungoo Empire

_in_1530.png)

Beginnings

Located in a remote, hard-to-reach corner east of the Pegu Yoma range, Toungoo had always been a troublesome province. It raised repeated rebellions throughout the 14th and 15th centuries against its overlords at Pinya and Ava, usually with Hanthawaddy Pegu's help. In 1494, Toungoo raided Pegu's territory without its overlord Ava's permission, and barely survived a strong counterattack by Pegu in 1495–1496. Mingyi Nyo, viceroy of Toungoo, would not make war against the larger neighbour for the remainder of his life.[36] Mingyi Nyo declared independence from Ava in 1510, and largely stayed out of the fighting raging between Ava and the Confederation of Shan States. When Ava fell to the combined forces of the Confederation and Prome in 1527, many people fled to Toungoo, the only region in Upper Burma at peace.[36][37]

Lower Burma and Central Burma (1534–1545)

.png)

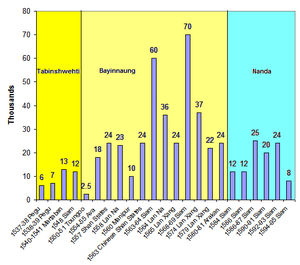

When Tabinshwehti came to power in 1530, Toungoo was now the only ethnic Burman-led kingdom, and one surrounded by much larger kingdoms. Fortunately for Toungoo, the Confederation was distracted by internal leadership disputes, and Hanthawaddy, then the most powerful kingdom of all post-Pagan kingdoms, was weakly led.

Tabinshwehti decided not to wait until the larger kingdoms' attention turned to him. Tabinshwehti and his deputy Bayinnaung selected a weakly led Hanthawaddy as their first target. Their initial dry-season raids in 1534–1535, 1535–1536, and 1536–1537 all failed against Pegu's fortified defences aided by foreign mercenaries and Portuguese firearms. Toungoo armies had only 6,000 to 7,000 men, and did not yet have access to firearms.[38] Finally, Toungoo used a stratagem to create a split in the Hanthawaddy camp, and took Pegu without firing a shot. After the Battle of Naungyo, much of Lower Burma came under Toungoo rule by early 1539.[39] Toungoo forces then sacked the last Hanthawaddy holdout, Martaban in May 1541, after a siege of seven months. After the mass execution at Martaban, southern territories (present-day Mon State) to the Siamese frontier submitted.[39][40]

The conquest of Martaban now gave the upstart regime of Tabinshwehti complete control of the maritime trade and ports of the Hanthawaddy Kingdom. More importantly, Toungoo now had access to Portuguese firearms, which would prove crucial in its future campaigns.[40]

Toungoo forces next attacked the Prome Kingdom, and drove back Prome's overlord Confederation and ally Arakan. After a five months' siege, Prome was mercilessly sacked in May 1542.[41][42] In retaliation, the Confederation, consisted of seven Shan states, launched a major land and naval invasion in November 1543.[43] But the invasion force was driven back, and was followed up by Toungoo forces which took as far north as the old imperial capital of Pagan. Tabinshwehti was crowned king at Pagan in July 1544.[42][44] Ava did raid Salin in late 1544/early 1545 but the attack was easily repulsed.[44]

Arakan (1545–1547)

Tabinshwehti then turned to Arakan, ally of Prome, invading the western kingdom by sea and land in October 1546. The combined forces quickly advanced to Mrauk-U but could not make any headway against the heavily fortified capital for the next three months. Hearing that the Siamese forces were raiding the frontier, Tabinshwehti agreed to a truce, and withdrew in February 1547.[45]

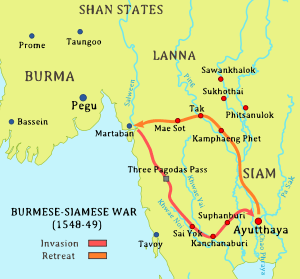

Siam (1547–1549)

Back from Arakan, Tabinshwehti looked east to Siam, which had occupied what he considered his territory. His response to "Siamese incursions" would launch the centuries-long Burmese–Siamese Wars between Burma and Siam. Siamese sources deny that Siam began the hostilities; rather, it was Burma's attempt to expand its territory eastwards taking advantage of a political crisis in Ayutthaya that started the hostilities.[46] (Either side's claim cannot be discounted since frontiers in the pre-modern period were less defined and often overlapped.[47] The Tavoy frontier remained a contested region well into the 18th century.) The Burmese king sent a sizeable force (4000 naval, 8000 land troops) led by Gen. Saw Lagun Ein of Martaban to drive out the Siamese forces from Ye and Tavoy in late 1547.[48][note 1] Saw Lagun Ein's forces defeated Siamese forces led by the governor of Kanchanaburi, and retook down to Tavoy.[49]

Tabinshwehti was not satisfied, and planned an invasion of Siam itself. Next year, near the end of the rainy season on 14 October 1548, (13th waxing of Tazaungmon 910 ME), 12,000 strong Toungoo forces led by Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung invaded Siam via the Three Pagodas Pass.[50][51] The Burmese forces overcame Siamese defences, and advanced to the capital city of Ayutthaya. But they could not take the heavily fortified city. One month into the siege, in January 1549, Siamese counterattacks broke the siege, and drove back the invasion force. On retreat, the Burmese tried to take Kamphaeng Phet, but it too was well defended by Portuguese mercenaries. Fortunately for the Burmese, they caught two important Siamese nobles (the heir apparent Prince Ramesuan, and Prince Thammaracha of Phitsanulok) in some open fighting, and negotiated a safe retreat in exchange for the nobles in February 1549.[52][note 2]

Lower Burma (1550–1552)

After Tabinshwehti was assassinated on 30 April 1550, the kingdom he and Bayinnaung had built up in the last 15 years instantly unravelled. Instead of acknowledging Bayinnaung as the next king, all the governors of the kingdom, including Bayinnaung's own kinsmen, set up their own fiefdoms.

Bayinnaung then set out to reclaim the kingdom. Starting with a small army of 2500 loyal followers, Bayinnaung first attacked native city of Toungoo where his brother Minkhaung had proclaimed himself king. After a siege of four months, Minkhaung surrendered, and was pardoned by his brother. On 11 January 1551, Bayinnaung was formally proclaimed king.[53] Bayinnaung then received tribute from fiefs throughout central Burma, and Martaban in the south.[54] Only Prome and Pegu in Lower Burma remained defiant. Bayinnaung captured Prome on 30 August 1551 after a five months' siege.[55][56] On 12 March 1552, Bayinnaung defeated Pegu's ruler Smim Htaw in single combat on elephants, and the victor's forces brutally sacked the city.[57][58]

Confederation of Shan states (1554–1557)

The Confederation-controlled Ava was next. Bayinnaung made extensive preparations, assembling a large invasion force (18,000 men, 900 horses, 80 elephants, 140 war boats). In December 1554, the Toungoo land and naval forces invaded. Within a month, the invasion forces held complete command of the river and the country. On 22 January 1555, the southern forces took the city.[59][60]

Bayinnaung then planned to follow up to the Confederation's home states to prevent future Shan raids into Upper Burma. With the entire Irrawaddy valley under his control, he was able to raise a large army of 24,000 men, 1200 horses and 60 elephants, and invaded the Shan states in January 1557. The massive show of force worked. Shan states one after another submitted with minimal resistance. By March 1557, Bayinnaung in one stroke controlled all cis-Salween (Thanlwin) Shan states from the Patkai range at the Assamese border in the northwest to Mohnyin (Mong Yang), Mogaung (Mong Kawng) in present-day Kachin State to Momeik (Mong Mit) Thibaw (Hsipaw), and Mone (Mong Nai) in the east.

Lan Na (1558)

Mone, one of the largest Shan states controlling Nyaungshwe (Yawnghwe) and Mobye (Mong Pai), revolted soon after the army left. Its sawbwa was a brother of the king of Lan Na (Chiang Mai). In November 1557, Bayinnaung's 23,000-strong forces reinvaded, and easily defeated Mone's forces. The sawbwa fled to Chiang Mai.[61]

Bayinnaung pursued the fugitive sawbwa, and arrived at the gates of Chiang Mai after 45 days of arduous march. The king of Lan Na surrendered without a fight on 2 April 1558.[62] By having acquired Mone and Lan Na, Bayinnaung had unknowingly become involved in the dynastic politics of middle Tai country. The ruler of Lan Xang Setthathirath was of Lan Na royalty, and wanted to regain his home kingdom. He attacked Chiang Mai in early 1559 but was repulsed.[62] Setthathirath would prove a thorn to Bayinnaung in years to come.

Manipur (1560)

The small kingdom of Manipur was next. A three-pronged invasion (10,000 men, 300 horses, 30 elephants) led by Gen. Binnya Dala faced minimal resistance, and achieved formal surrender c. February 1560.[63]

Farther Shan states (1562–1563)

In 1562, Bayinnaung looked to bring farther (trans-Salween) Shan states (present-day Kengtung in Shan State, and southern Yunnan) into his fold, ostensibly to prevent attacks on his territories. Again, he assembled a massive army (24,000 men, 1,000 horses, 80 elephants).[64] Prior to the invasion, on 16 December 1562, Kengtung submitted. By March 1563, a two-pronged invasion of the Taping valley had secured the allegiance of the farther Shan states.[65] (Note that these states at the Chinese border continued to pay dual tribute to both Burma and China down to the 19th century.)

Siam (1563–1564)

Bayinnaung now looked to Siam, which successfully fought off the first Burmese invasion in 1547–1549. However, Bayinnaung now had a far larger empire at his disposal. Knowing that Siam be much more difficult than Shan states and Lan Na campaigns, Bayinnaung assembled the largest army yet—60,000 men, 2400 horses and 360 elephants,[66] two and a half times larger than his previous high. The army would have been larger but the ruler of Chiang Mai, Mekuti, did not send in his share of the levy.

Four Burmese armies invaded northern Siam in November 1563, and had overcome Siamese stands at Kamphaeng Phet, Sukhothai and Phitsanulok by January 1564. Armies then came down on Ayutthaya but were kept at bay for days by Portuguese warships and batteries at the harbour. Siamese defences collapsed after the Burmese captured the Portuguese ships on 7 February 1564 (Monday, 11th waning of Tabodwe 925 ME). King Maha Chakkraphat of Siam surrendered on 18 February 1564 (Friday, 8th waxing of Tabaung 925 ME).[67] The king and crown prince Ramesuan were brought back to Pegu as hostages. Bayinnaung left Mahinthrathirat, one of Maha Chakkraphat's sons as vassal king, along with a garrison of 3,000 men.[68]

Lan Na and Lan Xang (1564–1565)

Bayinnaung still needed to settle the affairs at Lan Na which was in revolt, as well as with Lan Xang which had encouraged Lan Na. His 36,000-strong armies recaptured Chiang Mai without a fight in November 1564. Bayinnaung installed Mahadewi as queen regnant of Lan Na.[69] The army then attacked Lan Xang, capturing Vientiane in early 1765. Burmese troops fruitlessly chased Setthathirath's men, and many died of starvation and disease. By 1567, Setthathirath had retaken the capital.[68]

Siam (1568–1569)

In early 1568, the captive Siamese king, Maha Chakkraphat, who had become a monk, successfully convinced Bayinnaung to allow him to go back to Ayutthaya on pilgrimage. Upon his arrival, in May 1568, he disrobed and revolted. He also entered into an alliance with Setthathirath of Lan Xang. On 30 May 1568, a dismayed Bayinnaung sent an army of 6,000 to reinforce the defences at Phitsanulok, whose ruler had remained loyal to him. Phitsanulok withstood the siege by joint Siamese and Lan Xang forces till October when the besiegers withdrew to avoid what was to come. On 27 November 1568, 55,000-strong Burmese armies arrived at Phitsanulok.[70] Reinforced at Phitsanulok, combined armies of 70,000 marched down to Ayutthaya, and laid siege to the city in December 1568.

A month into the siege, Maha Chakkraphat died, and was succeeded by Mahin in January 1564.[71] Setthathirath tried to break the siege but his army was severely defeated northeast of the city on 23 April 1569.[72] Mahin finally offered to surrender but the offer was not accepted.[73] The city finally fell on 8 August 1569.[71] Bayinnaung appointed Maha Thammaracha, the viceroy of Phitsanulok, as vassal king on 30 September 1569.[74] The Burmese rule would not be challenged for another 15 years, until after Bayinnaung's death.

Lan Xang (1569–1574)

For Bayinnaung, the work was not yet done. On 15 October 1569, Bayinnaung at Ayutthaya led several regiments of his wounded army to invade Lan Xang via Phitsanulok. Setthathirath again fled Vientiane. Bayinnaung's men pursued but could not find him. Tired by long marches in a mountainous country, the Burmese army gave up and left Vientiane in May 1570.[75] Another expedition in 1572 after Setthathirath's death also failed to bring order. Finally, the king himself led another expedition, and put his nominee on the Lan Xang throne in November 1574. Aside from a minor rebellion in 1579, Lan Xang gave no trouble for the rest of Bayinnaung's reign.[76]

Arakan (1580–1581)

On 9 September 1580, Bayinnaung sent a large land and naval invasion force to bring Arakan, which was not yet part of his realm, the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia.[77] The combined forces (24,000 men, 1,200 horses, 120 elephants, 1,300 vessels) easily took Sandoway but did not proceed, awaiting the king's orders. The royal orders never came. The invasion forces withdrew in November 1581 after Bayinnaung's death.

Collapse of Toungoo Empire

Ava (1583–1584)

Bayinnaung's massive empire began to unravel soon after his death. He had controlled his vast empire not only by exercising his massive military power but also by establishing personal connections with the vassal kings. The vassal kings were loyal to him as the universal ruler, Cakkavatti, not to the Kingdom of Toungoo. Bayinnaung's eldest son Nanda succeeded but faced an impossible task of keeping the ties together. The problems began close to home. Bayinnaung's three brothers, viceroys of Ava, Prome and Toungoo, only nominally acknowledged their nephew. In October 1583, Nanda discovered a plot by Thado Minsaw of Ava to overthrow him, and after an extensive preparation, marched to Ava in March 1584. On 24 April 1584, Nanda defeated Thado Minsaw in their elephant duel, and took Ava.[78][79]

Siam (1584–1593)

Just nine days after the Ava rebellion was put down, on 3 May 1584, Siam also revolted. A few weeks earlier, the crown prince of Siam Naresuan's 6,000-strong army was hovering around Pegu instead of marching to Ava, as ordered. When Nanda retook Ava, Naresuan withdrew and at Martaban, declared independence. A hastily planned expedition followed Naresuan in the midst of the rainy season. The 12,000-strong Burmese army was caught unprepared by the flooded countryside by the Chao Phaya, and was nearly wiped out by Siamese on their war canoes.[80][81]

Another expedition was launched from Lan Na in March 1586. Mingyi Swa's 12,000-strong army could not take a heavily fortified Lampang, and had to withdraw in June. On 19 October 1586, Nanda himself led an army of 25,000, and invaded again. After several futile attacks on the heavily fortified Ayutthaya, the Burmese retreated in April 1587 after having suffered heavy casualties.[82] The failures at Siam began to affect Pegu's ability to hold on to other regions. Pegu faced other rebellions in Shan states, at Inya (1587–1588) and at Mogaung (1590–1592). In December 1590, Mingyi Swa's 20,000-strong army invaded again. Like in 1586, he could not get past the Siamese fort at Lampang, and was driven back in March 1591.

In December 1592, another invasion force of 24,000 tried again. The armies penetrated to Suphan Buri near Ayutthaya where they were met by Siamese forces led by Naresuan. On 8 February 1593, the two sides fought a battle in which Mingyi Swa was slain. The Burmese chronicles say Swa was killed by a Siamese mortar round[83] while the Siamese sources he was killed by Naresuan in a duel on their war elephants.[84] The Burmese forces retreated. It was the last of Pegu's Siamese campaigns. The main reason for Nanda's failure was that unlike his father who raised armies of 60,000 and 70,000, Nanda could never muster a force larger than 25,000 at any one time. Worse yet, he had frittered away Pegu's manpower. About 50,000 of the total of 93,000 men that marched in the five Siamese campaigns had perished.[81]

Unraveling of the empire

Pegu was now a completely spent force, vulnerable to internal rebellions and external invasions. In December 1594, Siamese armies invaded, and laid siege to Pegu in January 1595. Burmese armies from Toungoo and Chiang Mai relieved the siege in April 1595. However, the entire Tenasserim coast to Martaban now belonged to Siam.[85]

During the Siamese siege of Pegu, the viceroy of Prome, Mingyi Hnaung, revolted against his father. Nanda was powerless to take any action. Others soon followed. In early 1597, vassal kings of Toungoo and Chiang Mai also revolted. Another key viceroy, Nyaungyan of Ava nominally stayed loyal but offered no support.[86] Instead, Nyaungyan consolidated his position in Upper Burma throughout 1597.[87]

More chaos ensued. In September 1597, the rebellious Mingyi Hnaung of Prome was assassinated. Toungoo tried to pick off Prome but failed. Toungoo then formed an alliance with Arakan to attack Pegu. Combined Arakan and Toungoo forces laid siege to Pegu in April 1599. Nanda surrendered on 19 December 1599. The victors looted all the gold, silver and valuables that had been collected in the last 60 years by Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung. Before they left in late February 1600, the Arakanese burned down the city, including Bayinnaung's once-glittering Grand Palace.[88][89]

When Naresuan and his Siamese army showed up at Pegu to join the free-for-all, they found a smoldering city with the loot already taken away.[89] Naresuan hastily followed up to Toungoo, laying siege to the city in April 1600. But his supply lines were cut by the Arakanese from the rear, forcing the Siamese king to withdraw on 6 May 1600.[90] The Siamese forces suffered heavy losses in retreat. Only a small portion finally got back to Martaban.[91] It was the last time the Siamese ever invaded mainland Burma.

After the 1600 debacle, Naresuan turned north to Lan Na. In early 1602, King Nawrahta Minsaw of Lan Na who was facing attacks from Lan Xang agreed to become a Siamese tributary.[92]

Arakan

At the beginning of the 17th century, Arakan was at the height of its powers. Its dominion extended across a thousand miles of coastline from Chittagong to Syriam. In the previous century, the Arakanese with the help of Portuguese mercenaries had extended their grip of the trade through the Arakanese littoral up to Chittagong. It had grown wealthy from trade, including trade in slaves, which it actively raided from the Ganges delta.[93]

Portuguese insurrections

But its success depended greatly on the use of Portuguese mercenaries who proved unreliable and troublesome. Arakan lost the port city of Syriam in Lower Burma in 1603 when its Portuguese governor Filipe de Brito e Nicote declared that he was now loyal to the Portuguese viceroy of Goa. After two failed expeditions by the Arakanese navy to retake the port in 1604 and 1605, Arakan gave up its claims on the Lower Burma coastline.

Arakan's Portuguese troubles were not yet over. In 1609, its northern territories at the edge of Ganges delta and off Chittagong came under threat by the Portuguese mercenaries and the Mughal government in Bengal. In March 1609, 400 Portuguese mercenaries, led by Sebastian Gonzales Tibao, seized the Sandwip island. Meanwhile, the Mughal governor of Bengal tried to take over Noakhali District. Min Yazagyi was forced to enter into an alliance with the Portuguese to drive out the Mughals. After the Mughals were driven out, Gonzales promptly seized the Arakanese navy, and began raiding as far south as Lemro river. Later, the Portuguese viceroy at Goa sanctioned an attack on Mrauk-U itself. In November 1615, a fleet of 14 Portuguese galliots and 50 smaller war boats led by Francis de Meneses sailed up the Lemro. Alas, the fleet was driven back by Arakanese defences, which included broadsides of a few Dutch ships. Two years later, King Min Khamaung finally captured Sandwip, and put most of its inhabitants to death.[94][95]

Raids of Ganges Delta

Arakan grew even stronger, raiding the entire Sundarbans delta to Calcutta to the west and Murshidabad in the north. Tripura became a tributary. The Arakanese sacked Dhaka in 1625, after which the Mughal government withdrew to safer ground inland. Until 1666, when the Mughals came back with a vengeance, the Arakanese terrorised the entire delta, rounding up slaves whom they sold to the Europeans for a handsome profit.[95]

Decline of Arakan

In 1665, the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb decided to take action on the Arakanese marauders and launched the Mughal conquest of Chittagong. He also wanted to avenge for his brother Shah Shuja who was killed in exile by the Arakanese king. The Mughal viceroy of Bengal first lured the Portuguese mercenaries in the service of King Sanda Thudhamma guarding the Chittagong region to defect by giving them fiefs. Then the Mughal fleet took Sandwip in late 1665. In January 1666, a Mughal force of 6500 men and 288 boats took Chittagong after a 36-hours' siege. They subsequently took as far south as Ramu. Arakan had lost the Chittagong province which it had held since 1459.[96]

Arakan would not recover from the loss of Chittagong, and went into rapid decline. Central authority collapsed in the late 17th century. Sanda Wizaya (r. 1710–1731) briefly revived the kingdom. He went to war with Tripura, and raided Sandwip, Prome and Malun. But after his death, Arakan reverted to chaos where king after king was murdered and central authority barely existed. It was easily overrun by the Konbaung armies in 1784–1785.[96]

Nyaungyan restoration

While the interregnum that followed the fall of Pagan Empire lasted over 250 years (1287–1555), that following the fall of Pegu was relatively short-lived. One of Bayinnaung's sons, Nyaungyan, immediately began the reunification effort, successfully restoring central authority over Upper Burma and Shan States by 1606. Nyaungyan's successor Anaukpetlun had restored Bayinnaung's empire (except Siam and Lan Xang) by 1624.

Upper Burma and nearer Shan states (1597–1606)

After the fall of Pegu in December 1599, Lower Burma was in utter chaos, and politically fragmented among Toungoo, Prome, Arakanese/Portuguese Syriam and Siamese Martaban. In Upper Burma, however, Nyaungyan, viceroy of Ava, had been quietly consolidating his holdings since 1597. Though nominally loyal to Nanda, Nyaungyan provided no support to his overlord. In October 1599, just as Toungoo and Arakanese were laying siege on Pegu, Nyaungyan sent a force to reclaim Mohnyin, Mogaung, and Bhamo. After Pegu fell, Nyaungyan declared himself king on 25 February 1600.[97]

Nyaungyan then systematically reacquired nearer Shan states. He captured Nyaungshwe in February 1601, and the large strategic Shan state of Mone in July 1603, bringing his realm to the border of Siamese Lan Na.[98] In response, Naresuan of Siam marched in early 1605 to attack Mone but died at the border in April after which Siam ceased to be a military concern to Burma. In early 1606, his 7,000-strong forces took Theinni, Thibaw and Momeik but the king died during the campaign on 3 March 1606.

Lower Burma (1607–1613)

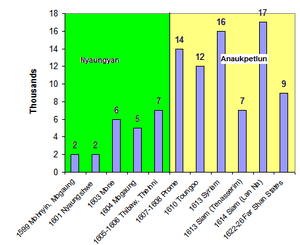

With Upper Burma securely under his control, Nyaungyan's successor Anaukpetlun marched south. His 14,000-strong land and naval forces sacked Prome on 13 July 1608 after a bloody siege of eight months.[99] His 12,000-strong forces then attacked Toungoo, then ruled by his cousin, Natshinnaung, in August 1610. After a siege of 23 days, Natshinnaung agreed to become a vassal on 4 September 1610.[100] But Natshinnaung was deeply unhappy with his reduced status, and secretly invited de Brito of Syriam to attack Toungoo. In July 1612, Syriam and Martaban forces ransacked the city for ten days, and left, taking Natshinnaung to Syriam.[101]

In response, Anaukpetlun's army of 13,000 (700 horses, 60 elephants) left Ava for Syriam on 26 December 1612. A flotilla of 80 war boats and 30 cargo boats (3,000 men) was also sent down the Irrawaddy to blockade the port. The Burmese forces overcame Portuguese outer defences, and finally blockaded the port on 24 February 1613. But Portuguese gunners and musketeers kept the Burmese at bay for 34 days while waiting for reinforcements from Goa to arrive. On 29 March 1613, however, the Burmese successfully brought down a section of the walls, from their tunnels below. The city was sacked. On 7 April 1613, de Brito his son and Natshinnaung were all executed by impalement.[102]

A month later, on 14 May 1613, Binnya Dala of Martaban, submitted. The ruler was nominally tributary to Siam but had ruled the region like a sovereign since the death of Naresuan in 1605. Alarmed, the Siamese sent an army to Ye, south of Martaban, to prevent the Burmese from marching down the coast. But the Siamese did not try to retake Martaban.[101]

Siam (1613–1614)

Anaukpetlun would not spend his scarce resources on subjugating Siam. His strategy was to pick off Siam's peripheral regions rather than launch a full-scale invasion. On 30 November 1613, he sent a small army of 4,000 (100 horses, 10 elephants) to drive out the Siamese from upper Tenasserim coast. On 26 December 1613, the army defeated the Siamese at Tavoy. The Burmese followed down to Tenasserim port itself. But the Burmese were driven back with heavy losses by the wealthy port's Portuguese broadsides in March 1614. The Siamese tried to retake Tavoy but failed.[103][104]

Anaukpetlun then switched theatres to Lan Na, which like Martaban before was only a nominal vassal of Siam. His armies of 17,000 invaded Lan Na on 30 April 1614 from Martaban in the south and Mone in the north. Lan Na's ruler, Thado Kyaw, desperately sought help. Help came from Lan Xang, not his overlord Siam. Despite the logistical troubles and the rainy season conditions, the Burmese armies finally achieved encirclement of Lan Na and Lan Xang forces in the Chiang Mai and Lanphun pocket in August 1614. After nearly five months, on 22 December 1614, the city surrendered.[105]

Siam would not make any attempts to recover Lan Na until 1663.

Farther Shan States (1622–1626)

Anaukpetlun then brought trans-Salween Shan states under his rule in the 1620s. In February 1622, his forces (4,000 men, 150 horses, 15 elephants) took Kengtung, which had been held by an ally of Lan Xang, after a fierce battle. Reinforced Burmese armies led by the king's brothers Thalun and Minye Kyawswa II invaded the Chinese Shan states in present-day southern Yunnan in May 1622. For the next 20 months, Burmese forces chased Kenghung troops. Finally in January 1624, Kenghung and Kengyun both surrendered. Kengyun promptly rebelled the following year but it was put down in December 1626 by the king's brothers.[106]

By then, Nyaungyan and Anaukpetlun had restored much of Bayinnaung's empire. Only Siam and Lan Xang remained outside the Restored Toungoo Empire. But the Burmese would not overstretch again. They would not launch major invasions against these neighbours until the 1760s.

Ming incursions (1651–1662)

In the 1650s, Burma became entangled in the dynastic changes in China. In 1651, Ming armies fleeing from the Qing forces entered Kengyun (east of Bhamo), which had paid tribute to both China and Burma. King Pindale sent five regiments to the front in October 1651. But the armies were driven back by the Ming in December 1651.[107] Pindale would not contest again.

In 1658, Zhu Youlang, one of the sons of the last Ming emperor, and his 700 followers were given permission to stay at Sagaing. In early 1659, other fleeing Ming armies entered the Shan states, and occupied Nyaungshwe and Mone with the intention to set up a kingdom for their emperor.[108] For the next two years, the Ming forces proved a menace to Upper Burma. Not only Pindale could not drive out the Ming but it was the Ming that continually threatened the Burmese capital itself, and ransacked Upper Burma districts. On 4 June 1661, Pye Min overthrew his ineffectual brother, and took over the command. He finally drove out the Ming by November 1661.[109]

The problems were not yet over for the Burmese. On 21 December 1661, a Qing army of 20,000 under Gen. Wu Sangui showed up at Ava, demanding the surrender of the Ming emperor. The emperor was handed over on 15 January 1662, and the Qing forces left a week later.[110]

Siamese invasions (1662–1664)

While Burma had its hands full with the Ming Chinese invasions, Siam's King Narai attempted to pick off the upper Tenasserim coast and Lan Na. He got Martaban to switch sides in March 1662, and occupied the coast. Fortunately for the Burmese, their troubles with the Ming were over. Their land and naval units recaptured Martaban and Tavoy by December 1662. They followed up on the retreating Siamese but were driven back near Kanchanaburi with heavy losses.[111][112]

Meanwhile, a much larger Siamese army invaded Lan Na, catching the Burmese command completely off guard. The Siamese captured Chiang Mai on 10 February 1663, and drove back Burmese forces that arrived belatedly. In November 1663, Siam launched a two-pronged invasion of the Tenasserim coast: Martaban and Moulmein in the north and Tavoy in the south. Burmese defences withstood several Siamese onslaughts until May 1664 when the invaders retreated before the rainy season arrived. Meanwhile, the Siamese garrison at Chiang Mai was holed up in a deserted city, and its troops were constantly ambushed by resistance forces whenever they ventured out of the city. In late November 1664, the Siamese evacuated Chiang Mai, and returned.[113]

This was the last major war between the two kingdoms until 1760 although they traded small raids in 1675–1676, and in 1700–1701.

Fall of Toungoo Dynasty

Lan Na (1727–1732)

In October 1727, the Burmese governor of Lan Na was assassinated because of high taxation. An army was rushed to Chiang Mai via Mone. The army retook the city after a fierce battle. But the army was ambushed by the rebels as the troops left the city in early 1728. Another expedition in 1731–1732 could not overcome the defences at Chiang Mai.[114] Southern Lan Na (Ping valley) was now independent of Ava.

Manipuri raids (1724–1749)

Manipur was a tributary to Burma in the 16th century (1560–1596) but had gone its own way since.[115][116] It raided Upper Chindwin region in 1647 and 1692.[115] However, in 1704, the raja of Manipur presented his daughter to Ava. Starting in the 1720s, Manipur under the leadership of Pamheiba (Gharib Nawaz) became a thorn to Upper Burma. In early 1724, the Manipuris raided Upper Burma. In response, an expedition force of 3,000 men marched to Manipur in November 1724. The army was ambushed in the swamps at Heirok, and retreated in haste.[117]

The Manipuris then returned ten years later. From 1735 to 1741, Manipuris raided the Upper Chindwin regions, increasingly deeper with each raid. Burmese defences were simply bypassed the Manipuris on their horseback. In December 1739, they reached as far as Sagaing, and looted and burned everything insight. The Burmese defences finally stopped them at Myedu in early 1741, with each side agreeing to an uneasy truce.[118] But the Manipuris had annexed the Kabaw valley.

The truce did not last. Another raid came all the way down to Ava in 1744. The last raid came in 1749. Upon arrival at Ava, the Manipuri chief found a large Burmese army, and presented his 12-year-old daughter instead, and left.[119]

Restored Hanthawaddy (1740–1752)

While Ava had its hands full with the Manipuri raids in Upper Burma, a rebellion broke out at Pegu in November 1740. Ethnic Mon officials selected Smim Htaw Buddhaketi, a cousin of the king at Ava, as their king. The court at Pegu consolidated its hold in Lower Burma. Starting in 1742, Pegu, with renegade Dutch and Portuguese musketeers, began its annual raids of the upcountry. Because of the Manipuri threat, Ava could only send small armies to the south in 1743 and 1744, neither of which made any mark.[120] The war "carried on languidly", with neither side achieving any lasting advantage until 1747.[121]

In December 1747, Binnya Dala came to power in Pegu, and the new king was determined to finish the war. He was not satisfied to gain independence for Lower Burma itself but determined to make Upper Burma its tributary. He stopped the annual raids and began planning for a decisive invasion. He sought and received French East India Company's support in firearms. Alarmed, Ava too sought support from China but no help materialised.[120]

In November 1751, Pegu launched a full-scale invasion by land and by river with a total strength of 30,000. Ava had prepared an extensive defensive line around Ava—a riverside fort at Sinbyukyun on the Irrawaddy, and a series of forts at Sintgaing, Tada-U and Pinya en route to Ava. By mid-January, the invasion forces had overcome Ava's defences, and laid siege to the city. On 21 March 1752, the invaders broke through the city's outer walls. Two days later, they breached the inner walls and took the city. The 266-year-old Toungoo Dynasty had fallen.[120][122]

Konbaung period

Konbaung Empire

Restored Hanthawaddy (1752–1757)

After the fall of Ava, many independent resistance movements sprang up across a panicked Upper Burma. Yet the Hanthawaddy command left less than 10,000 troops to pacify all of Upper Burma. Alaungpaya, who founded the Konbaung Dynasty, quickly emerged as the main resistance leader, and by taking advantage of Hanthawaddy's low troop levels, went on to conquer all of Upper Burma by the end of 1753. Hanthawaddy belatedly launched a full invasion in 1754 but it faltered. Konbaung forces invaded Lower Burma in January 1755, capturing the Irrawaddy delta and Dagon (Yangon) by May. The French defended Syriam held out for another 14 months but eventually fell in July 1756, ending French involvement in the war. The fall of the 17-year-old southern kingdom soon followed in May 1757 when Pegu was sacked.

Lan Na, Martaban, Tavoy and Sandoway all submitted after Pegu's fall.[123]

Manipur (1756–1758)

Alaungpaya, who grew up watching the Manipuri raids ransacking his home region year after year, was determined to return the favour as soon as he was able. In early 1756, he sent an expedition force to Manipur to "instill respect". The Burmese army defeated the Manipuri army, and ransacked the entire country, which the Manipuris call the First Devastation.[124][125] After Lower Burma was conquered, Alaungpaya himself led another expedition in November 1758, this time to place the Burmese nominee to the Manipuri throne. His armies invaded by the Khumbat route in the Mainpur valley, and overcame fierce Manipuri resistance at Palel, on their march to Imphal, the Manipuri capital. After Palel, the Burmese entered Imphal without firing a shot. The Konbaung armies, according to the Manipuris, then inflicted "one of the worst disasters in its history".[126] He brought back many Manipuri cavalry, who became an elite cavalry corps (the Cassay Horse) in the Burmese army.[127]

The Manipuri raja Ching-Thang Khomba (Jai Singh) fled into English Bengal, and would attempt to regain his kingdom for the next 24 years. With English East India Company's arms support, he invaded Manipur in 1763 but was driven back by Hsinbyushin in early 1764.

Negrais (1759)

The English East India Company had seized Negrais (Haigyi Island) at the southwestern tip of the Irrawaddy delta since April 1753 because they were concerned about the French influence over Pegu, and wanted their own foothold in Lower Burma. During the war with Hanthawaddy, Alaungpaya even offered to cede the island to England in return for military help. But no military help materialised. The English claimed they could not spare any arms because they too were engaged in their own bitter Seven Years' War against the French.[128] Yet the Company's agents sold ammunition and muskets to the Mon rebels in 1758. On 6 October 1759, a 2,000-strong Konbaung battalion overran the English fort, ending the first English colonial establishment in Burma for the time being.[129]

Siam (1759–1767)

_map_-_EN_-_001.jpg)

By 1759, Alaungpaya had reunified all of Burma plus Manipur and Lan Na. However, his hold on Lan Na and Tenasserim coast was still nominal. The Siamese who originally were concerned about the rising power of Restored Hanthawaddy now actively supported the ethnic Mon rebels operating in the upper Tenasserim coast. In December 1759, Alaungpaya and his 40,000-strong armies invaded the Tenasserim coast. They crossed over the Tenasserim Hills, and finally reached Ayutthaya on 11 April 1760. But only five days into the siege, the Burmese king suddenly fell ill and the Burmese withdrew. The king died three weeks later, ending the war.

The 1760 war was inconclusive. Although Burma had regained the upper Tenasserim coast to Tavoy, they still had to deal with Siamese supported rebellions in Lan Na (1761–1763) and at Tavoy (1764). The warfare resumed in August 1765, when two Burmese armies invaded again in a pincer movement on the Siamese capital. The Burmese armies took Ayutthaya in April 1767 after a 14-months' siege. The Burmese armies sacked the city and committed atrocities that mar the Burmese-Thai relations to the present. The Burmese were forced to withdraw a few months later due to the Chinese invasions of their homeland. Burma however had annexed the lower Tenasserim coast.

Laotian states (1765)

Between the two Siamese wars, Burma acquired the Laotian states of Vientiane and Luang Prabang. Vientiane was acquired without a fight in January 1765. Luang Prabang put up a fight but was defeated in March 1765. The move was to outflank Siam in their upcoming invasion. The Laotian states remained Burmese tributaries until 1778.

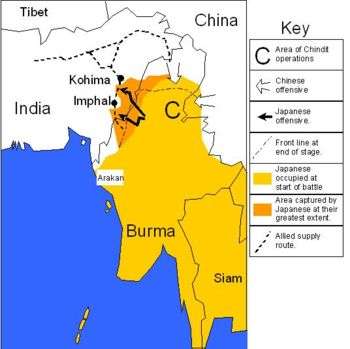

China (1765–1769)

Concerned by the Burmese consolidation of Shan states and Laotian states, China launched four invasions of Burma between 1765 and 1769. At first, the Qianlong Emperor envisaged an easy war, and sent in only the Green Standard troops stationed in Yunnan. The Qing invasion came as the majority of Burmese forces were deployed in their latest invasion of Siam. Nonetheless, battle-hardened Burmese troops defeated the first two invasions of 1765–1766 and 1766–1767 at the border. The regional conflict now escalated to a major war that involved military manoeuvres nationwide in both countries. The third invasion (1767–1768) led by the elite Manchu Bannermen nearly succeeded, penetrating deep into central Burma within a few days' march from Ava. But the Bannermen of northern China could not cope with unfamiliar tropical terrains and lethal endemic diseases, and were driven back with heavy losses. After the close-call, Hsinbyushin redeployed his armies from Siam to the Chinese front. The fourth and largest invasion got bogged down at the frontier. With the Qing forces completely encircled, a truce was reached between the field commanders of the two sides in December 1769.[130][131]

The Qing kept a heavy military line-up in the border areas of Yunnan for about one decade in an attempt to wage another war while imposing a ban on inter-border trade for two decades. When Burma and China resumed a diplomatic relationship in 1790, the Qing unilaterally viewed the act as Burmese submission, and claimed victory.[130] The war, which claimed the lives of over 70,000 Chinese soldiers and four commanders is sometimes described as "the most disastrous frontier war that the Qing Dynasty had ever waged",[130] and one that "assured Burmese independence and probably the independence of other states in Southeast Asia".[132] It has also been called the "greatest" of Burmese military victories.[133]

Nonetheless, the war took a heavy toll on the Burmese war capabilities. While Burmese losses were light compared to Chinese losses, when considered in proportion to the population, they were heavy.[134]

Siam (1775–1776)

In December 1774, a Siamese supported rebellion broke out at Lampang in Lan Na, and soon spread. On 15 January 1775, the rebels took Chiang Mai, and overthrew the Burmese installed government.[135] In November 1775, two Burmese armies of 35,000 were to invade Lan Na and Siam. But because of a mutiny by a senior commander, the southern army lost a significant portion of the troops. The remaining Burmese armies fought their way in. The northern army managed to capture Chiang Mai, albeit at a great cost, and the southern army took Sukhothai and Phitsanulok in central Siam. However, the invasion forces were too small to overcome the Siamese defences, and were bogged down. The armies withdrew in June 1776 after Hsinbyushin died.

Hsinbyushin's successor Singu stopped the war with Siam, and demobilised much of the army. The decision was well received by the war-torn country. The people had grown tired of constant conscriptions to fight in "ever-lasting wars" in remote regions they had never heard of.[136] But the king had unwittingly given up Chiang Mai, which proved to be the end of two centuries of Burmese rule there. Likewise, Singu took no action in 1778 when Vientiane and Luang Prabang stopped paying tribute, and came under Siam's sphere of influence.[137]

Manipur (1775–1782)

The only region in which Singu maintained military action was Manipur, where he inherited another war from his father. The former Manipuri king Jai Singh, whom the Burmese last drove out in 1770, made four more attempts to oust the Burmese nominee between 1775 and 1782 from his base in Cachar. The Burmese drove him back each time but were unable to capture him. The army gained "barren victories" in Cachar and Jaintia where the rajas of the two small states agreed to pay a token tribute. But the tribute came at a high cost: the army lost 20,000 men, partly by fever over the years.[138] After Singu's dethronement in 1782, the new king, Bodawpaya stopped the invasions. Manipur was again independent.

Arakan (1784–1785)

By the 1770s, Arakan was a shadow of her former self. Central authority had not existed since 1731. Desperate Arakanese nobles asked King Singu to intervene but Singu refused.[139] In 1784, the Arakanese nobles again asked the new king Bodawpaya, who agreed. An invasion force of over 20,000 men (2500 horses and 200 elephants) consisted of land and naval units invaded on 2 December 1784. The combined forces faced little opposition en route to Mrauk-U, and took the capital on 2 January 1785, ending five centuries of Arakanese independence.[140][141]

The army was originally welcomed by the populace who actually greeted them with music along the invasion route. But they soon discovered to their horror, the invasion army's wanton destruction, killings, and especially, the unconscionable removal of their national symbol, the Mahamuni Buddha. They soon organised a resistance movement that would eventually lead the Burmese to the first war with the British in 1824.[139]

Siam (1785–1812)

The relative ease with which Arakan was taken whetted Bodawpaya's appetite for war. Only a few months after Arakan, in early 1785, he sent an expedition force to take Junkceylon (Phuket) to prevent foreign arms shipment to Siam but the invasion force was driven back. In mid-October 1785, he launched a four-pronged invasion towards Chiang Mai, Tak, Kanchanaburi and Junkceylon. The combined strength was about 50,000 men. The hastily planned invasion had not made proper arrangements for transportation or supplies, and was a total disaster. Aside from the northern army which took Chiang Mai and swept down to Lampang, the southern armies were driven back, or in one case, nearly annihilated. The invasion armies withdrew in disarray in late January 1786.[142] So severe was the defeat that the invasion turned out to be the last full-scale invasion of Siam by Burma.

Siam was now on the offensive, and tried to regain the Tenasserim coast they had lost since 1765. In 1787, its forces laid siege to Tavoy but were unsuccessful. In March 1792, they got the governor of Tavoy to switch sides, and sent in a large army to retake Tenasserim. But the Siamese could not take Mergui and had to lay siege to the city. Initial Burmese efforts to retake Tavoy failed. The Burmese sent in another force after the rainy season and in December, recovered Tavoy and relieved Mergui which had held on for nine months.[143]

Having failed in the south, Siam then tried north. After the 1786 war, Siam consolidated its control of Lan Na, and in 1794, took over the Laotian state of Luang Prabang, its erstwhile ally against the Burmese. In response, Burma sent in a small expedition in 1797 to Chiang Mai and Luang Prabang to check the Siamese but it failed to make any impression. Undeterred, the Siamese army invaded Burmese territories of Kengtung and Kenghung (Sipsongpanna) in November 1803, laying siege to both towns. They withdrew in early 1804, taking back many conscripts with them.[144] Burmese forces followed up on the retreating Siamese into Lan Na but were driven back at Chiang Saen at the border. Siam did not give up. In 1807–1808, Siamese troops based out of their vassal Luang Prabang tried to take over Sipsongpanna but were driven back. (In 1822, they again encouraged the ruler of Sipsongpanna to revolt. Burmese troops from Kengtung arrested the rebel sawbwa.)[145]

While Siam was focused on extending its northern border, Burma was focused on extending its southern border. Burma sent four expeditions between 1809 and 1812 to take the tin rich Junkceylon island. Aside from a few temporary victories and the sacking of Thalang, the army was driven back each time.[144][146][147]

Manipur (1814–1820)

After the four failed expeditions on Junkceylon, Bodawpaya gave up on wars with Siam, and now looked to the small states to the west. The first target was Manipur, which had regained independence from Burma since 1782. In February 1814, he sent an expedition force to place his nominee Marjit Singh to the Manipuri throne. The Manipuri army was defeated after heavy fighting, and its raja Chourjit Singh fled into Cachar.[148][149]

However, Marjit Singh revolted after Bodawpaya died in June 1819. The new king Bagyidaw sent an expedition force of 25,000 (3,000 horses) in October 1819. Gen. Maha Bandula reconquered Manipur but the raja escaped to neighbouring Cachar. In November 1820, the fallen raja's forces laid siege to the Burmese garrison at Imphal, and withdrew only when Burmese reinforcements were approaching. Nonetheless, the raja continued to raid Manipur with British support using his bases from Cachar and Jaintia, which had been declared as British protectorates, to the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824.[150]

Assam (1816–1822)

The kingdom of Assam was the last conquest of Bodawpaya. In December 1816, he sent a 16,000-strong force to Assam to install his nominee, Chandra Kanta Singh, to the Assamese throne. From their northernmost forts in Hukawng Valley in present-day northern Kachin State, the Burmese army crossed the 9,000-foot high Himalayan Patkai range, and finally entered Assam in early 1817. The army decisively defeated the Assamese army at the battle of Kathalguri, near the Assamese capital Jorhat. A pro-Burmese minister Badan Chandra was installed, with Singh as the nominal king.[151] The army left in April 1817 but instabilities resumed soon after, and Singh had to flee Jorhat. The army had to return in February 1819, and reinstated Singh. A large portion of the army remained in Assam to hunt down the rebels in Upper Assam. The authority rested with the Burmese commanders, not the nominal king.[152]

Unhappy with the arrangement, Singh switched his allegiance to the British in April 1821, and tried to drive out the Burmese. His first attack on the Burmese garrison at Gauhati in September 1821 failed. But reinforced by British arms and personnel, Singh took Gauhati in January 1822, and marched to Jorhat. But the capital had been reinforced by a 20,000-strong army led by Bandula, who had just arrived. Bandula defeated Singh on 17 April 1822 at Mahgarh near Jorhat.[152] Singh fell back to Gauhati but was defeated by Gen. Maha Thilawa on 3 June 1822. The fallen king fled to the British territory, and continued to make raids in the years leading to the First Anglo-Burmese War.

Fall of Burmese monarchy

First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826)

By 1822, the conquests of Manipur and Assam had brought a long border between British India and Burma. The British at Calcutta had their own designs on the region, and actively supported rebellions in Manipur, Assam and Arakan. Calcutta unilaterally declared Cachar and Jaintia British protectorates, and sent in troops. Cross border raids into Arakan, Manipur and from British territories vexed the Burmese.[153] In January 1824, Bandula allowed Burmese troops into Cachar and Jaintia in pursuit of the rebels. The British sent in their own force to meet the Burmese in Cachar, resulting in the first clashes between the two. The war formally broke out on 5 March 1824, following border clashes in Arakan.

At first, battle hardened Burmese forces were able to push back the British forces in Cachar, Jaintia and East Bengal.[154] Instead of fighting in the difficult terrain, which represented "a formidable obstacle to the march of a European force", the British took the fight to the Burmese mainland. On 11 May 1824, a British naval force of 11,000 took Rangoon (Yangon), taking the Burmese by surprise. The Burmese forces tried multiple times to retake the city but failed. In April 1825, Bandula fell at the battle of Danubyu, and the British took up to Prome. The Burmese tried to retake Prome in a last-ditch attempt but were driven back in December. On 24 February 1826, the Burmese had to agree to British terms without discussion. Per the Treaty of Yandabo, Burma was forced to cede Arakan, Manipur, Assam and Tenasserim and pay a large indemnity of one million pounds sterling.

The war was the longest and most expensive war in British Indian history. Fifteen thousand European and Indian soldiers died, together with an unknown number of Burmese army and civilian casualties. The campaign cost the British five million pounds sterling to 13 million pounds sterling (roughly 18.5 billion to 48 billion in 2006 US dollars) that led to a severe economic crisis in British India in 1833.[155][156] For the Burmese, it was the beginning of the end of their independence. The Third Burmese Empire, for a brief moment the terror of British India, was crippled and no longer a threat to the eastern frontier of British India. The Burmese would be crushed for years to come by repaying the large indemnity.[157]

Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852)

By 1851, Burma had been greatly weakened, and the British were ready to pounce again. Using a fine of two British ships by the mayor of Rangoon as the excuse, Lord Dalhousie, governor-general of India, sent an ultimatum to rescind the fine, remove the offending mayor, and pay a fine of a one thousand pounds. The Burmese neither wanted nor were ready for a war. They quickly accepted the British demands. But the British officer on the scene, Commodore George Lambert, blockaded the port of Rangoon anyway. On 18 February 1852, Dalhousie increased the demand a hundredfold to one hundred thousand pounds sterling. On 12 April 1852, the British navy invaded Rangoon.[158][159]

King Pagan sent four armies to meet the enemy. The Burmese put up tough resistance at Bassein (Pathein) and Pegu but by June, much of Lower Burma belonged to the invaders. After the end of the rainy season, in November, the British took Prome, and pushed up to Myede on the Irrawaddy, and took Toungoo on the Sittaung, facing minimal Burmese resistance. In December, Prince of Mindon raised a rebellion against his brother the king. On 20 December 1852, the British issued a proclamation of annexation, taking Lower Burma, up to the latitude running directly east-west across the country to the borders of Karenni states, 6 miles (9.65 km) north of Myede (and Toungoo).[160] It took three years to "pacify" the province. Burmese resistance leader Myat Tun, with 4,000 followers, waged guerrilla warfare, repulsing three British attacks before succumbing to a fourth one led by a brigadier general.[161] In 1857, an ethnic Karen leader began another round of guerrilla warfare in the Irrawaddy delta, and was put down only after 8 years.[162]

Siam (1849–1855)

Although it failed to dislodge the Burmese from Kengtung and Sipsongpanna at the beginning of the century (1803–1808), Siam never gave up its claims on these lands. They tested the waters in 1849, by raiding as far north as Kengtung. But when the Second Anglo-Burmese War started, the Siamese viewed it as their opportunity to take over the trans-Salween states. In late 1852, a large infantry and elephant force marched from Chiang Mai and launched a two-pronged invasion of Kengtung. Burma could respond only after the new king Mindon had seized power in February 1853. Because he was still concerned about the British threat, Mindon could only send several thousand infantry troops from the Mone (Mong Nai) garrison to relieve the Siamese siege of Kengtung. With the troops by Kenghung sawbwa, the Burmese eventually drove out the Siamese but only after heavy loss of life. In 1854, the largest Siamese invasion force, consisted of Laotian levies, tried once more. But this time, with the British front quiet, the Burmese were ready. Mindon had deployed a larger, well-equipped army (with artillery corps and 3,000 cavalry). The Siamese forces again reached Kengtung but could not break through.[163][164] The Siamese forces withdrew to the border in May 1855.[165]

Karenni states (1875)

In the early 1870s, the British again eyed Burmese territories north, this time, the Karenni states, which were the southernmost part of the Shan states, and ruled by its hereditary Shan sawbwas. In 1873, Mindon had to send troops to quell a British supported rebellion. The British were adamant, demanding that Mandalay recognise the "independence" of the Karenni states, and that anything less would be deemed an act of war. Facing a certain defeat, the king chose to swallow a "bitter pill", and signed away the territory in March 1875. Per treaty, the Burmese troops withdrew from the territory but the British troops remained in the newly "independent" territory, causing Mindon to lose considerable prestige at home.[166][167] (Indeed, the British would conveniently drop the pretense that the Karenni states were independent in 1892 after the Third Anglo-Burmese War).

Shan states rebellions (1878–1885)

In October 1878, Thibaw, a junior prince, succeeded the throne, and soon proved an ineffectual king. His authority quickly waned, especially in the hill regions, which had paid nominal tribute even during his father's reign. Indeed, Mindon had held on to the fealty of Shan states not by force but by maintaining personal relationships. But Thibaw did not command any respect. The Shan state of Mone first revolted, refusing to attend the king's coronation. Soon, the rebellion spread eastward. For six years, thousands of Thibaw's troops were sent to put down the revolt, "trying in vain to resurrect a long-dead empire".[168]

Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885)

In 1885, the British sought to annexe the rest of the kingdom. They had been concerned by the Burmese efforts to form an alliance with the French, who were consolidating their holdings in nearby French Indochina. Burma was trying to pursue the same strategy as Siam, as a buffer between the British and the French. But the British viewed Burma as their sphere of influence, and sent in an invasion force on 7 November 1885. The invaders easily overcame minimal Burmese resistance, and took Mandalay on 29 November 1885. The Burmese king Thibaw and the royal family were taken away to India. Burma was formally annexed by the British on 1 January 1886. The millennium old Burmese monarchy had ended.

Although it took less than a month to occupy Mandalay, the British spent another 10 years to pacify the rest of the country. Over a year into the annexation, the country was still in chaos. In 1887, a 32,000-strong army led by two major generals and six brigadier generals was dispatched to quell the instabilities, and to annexe the hill regions.[169] The Burmese resistance in the low country was hammered down by 1890 but the hill regions proved particularly troublesome for the colonizers. A five-month expedition in 1887–1888 brought cis-Salween Shan states under control as British protectorates. The army was then forced to put down insurgencies all over the region. It finally brought Kengtung into the fold in March 1890, completing the annexation of Shan states. But rebellions broke out again in northern Shan states at Hsenwi, Lashio and Bhamo in 1892. In 1894, the British also had to chase down rebels in the Karenni states, which they had formally annexed since 1892.[170] In the west, it took the British forces 15 months to overcome the Chin resistance before taking Falam in March 1891. But the British had to spend another five difficult years in the unfamiliar hill country to finish off the Chin resistance. Finally, in 1896, the British proclaimed the Chin Hills to be a part of Burma.[171]

Colonial era

The British had used mainly Indian and Gurkha troops to conquer and pacify the country. In a divide-and-rule manoeuvre, the British enforced their rule in the province of Burma mainly with Indian troops later joined by indigenous military units of three indigenous ethnic minorities: the Karen, the Kachin and the Chin. The British did not trust the Burmans. Before 1937, with few exceptions, no Burmans were allowed to serve in the military.[172]

World War I and interwar period