Jaco Pastorius

| Jaco Pastorius | |

|---|---|

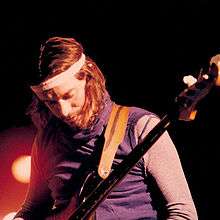

Pastorius in concert in 1986 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Francis Anthony Pastorius III |

| Born |

December 1, 1951 Norristown, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died |

September 21, 1987 (aged 35) Wilton Manors, Florida |

| Genres | Jazz, jazz fusion, big band, folk-jazz, funk |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, producer |

| Instruments | Bass |

| Years active | 1964–1987 |

| Labels | Epic, Warner Bros., Columbia, ECM, CBS, Elektra |

| Associated acts | Pat Metheny, Joni Mitchell, Weather Report, Word of Mouth |

| Website |

jacopastorius |

John Francis Anthony "Jaco" Pastorius III (/ˈdʒɑːkoʊ pæsˈtɔːriəs/, December 1, 1951 – September 21, 1987) was an American jazz musician, composer, big band leader and electric bass player. He is best known for his work with Weather Report from 1976 to 1981, as well as work with artists including Joni Mitchell, Pat Metheny, and his own solo projects.[1]

As a musician, he developed an influential approach to bass playing that combined the use of complex harmony with virtuosic technique. His signature approach employed Latin-influenced funk, lyrical solos on fretless bass, bass chords, and innovative use of harmonics. He was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame in 1988, one of only seven bassists so honored (and the only electric bassist).

Early life

Pastorius was born December 1, 1951, in Norristown, Pennsylvania,[2] to Jack Pastorius (big band singer and drummer) and Stephanie Katherine Haapala Pastorius;[3] and was the first of their three children. Jaco's grandmother was a Finn, named Kaisa Eriika Isojärvi. Jaco Pastorius was of Finnish, Sami,[4] German, Swedish and Irish ancestry.[5]

Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Oakland Park, Florida (near Fort Lauderdale). Pastorius went to elementary and middle school at St. Clement's Catholic School in Wilton Manors, and he was an altar boy at the adjoining church.[6]

Pastorius formed his first band named the Sonics (not the Seattle-based band of the same name), along with John Caputo and Dean Noel. He went to high school at Northeast High in Oakland Park, Florida.[7] He was a talented athlete with skills in football, basketball, and baseball, and he picked up music at an early age. He took the name "Anthony" at his confirmation.[7]

He loved baseball and often watched it with his father. Pastorius's nickname was influenced by his love of sports and also by the umpire Jocko Conlan.[7] He changed the spelling from "Jocko" to "Jaco" after the pianist Alex Darqui sent him a note. Darqui, who was French, assumed "Jaco" was the correct spelling. Pastorius liked the new spelling.[7] Jaco Pastorius had a second nickname, given to him by his younger brother Gregory: "Mowgli", after the wild young boy in Rudyard Kipling's children's classic, The Jungle Book. Gregory gave him the nickname in reference to his seemingly endless energy as a child.[7] Pastorius later established his music publishing company as Mowgli Music.

Career

.jpg)

Pastorius started out following in the footsteps of his father Jack, playing the drums until he injured his wrist playing football at age 13. The damage to his wrist was severe enough to warrant corrective surgery and ultimately inhibited his ability to play drums.[7] At the time, he had been playing with a local band, Las Olas Brass. When the band's bass player, David Neubauer, decided to quit the band, Pastorius bought an electric bass from a local pawn shop for $15 and began to learn to play[8] with drummer Rich Franks, becoming the bassist for the band.[9]

By 1968–1969, at the age of 17, Pastorius had begun to appreciate jazz and had saved enough money to buy an upright bass. Its deep, mellow tone appealed to him, though it strained his finances. Pastorius had difficulty maintaining the instrument, which he attributed to the humidity of his Florida home. He woke one day to find that his costly upright bass had cracked. Following this development, he traded it in for a 1962 Fender Jazz Bass.[10]

Pastorius's first real break came when he became bass player for Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders. He also played on various local R&B and jazz records during that time, such as with Little Beaver and Ira Sullivan.

In 1973 at the age of 22, Pastorius was teaching bass at the University of Miami. While at UM he made contact with many of the great music students who were going through the program at that time, including Pat Metheny, who enrolled in 1972 but was too advanced a player to remain a student and likewise became part of the UM music faculty at the age of 18.

In 1974, Pastorius began playing with Metheny. They recorded together, first with Paul Bley as leader and Bruce Ditmas on drums, on an album later titled "Jaco," for pianist Paul Bley and Carol Goss's Improvising Artists label (it was Metheny's recording debut), then with drummer Bob Moses on a trio album on the ECM label, entitled Bright Size Life (1976).

Debut album

In 1975, Pastorius was introduced to Blood, Sweat & Tears drummer Bobby Colomby, who had been asked by Columbia Records to find "new talent" for their jazz division.[11] Pastorius's first album, produced by Colomby, was Jaco Pastorius (1976), a breakthrough album for the electric bass.[2] Many consider this the finest bass album ever recorded;[2] it was widely praised by critics. The album also boasted a lineup of heavyweights in the jazz community at the time – including Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, David Sanborn, Lenny White, Hubert Laws, Don Alias, and Michael Brecker. Even the soul singers Sam & Dave reunited to appear on the track "Come On, Come Over".[12]

Weather Report

.jpg)

Some time prior to the sessions for his debut album, he attended a concert in Miami by the jazz band Weather Report. After the concert, he approached keyboardist Joe Zawinul, who fronted the band. According to Zawinul, Pastorius walked up to him after the concert and talked about the performance, saying that it was all right but that he had expected more.[13] He then went on to introduce himself, adding that he was the greatest bass player in the world. An unamused Zawinul at first told him to "get the fuck outta here."[14] According to Zawinul (quoted in Milkowski's book), Pastorius persisted and as they talked the Austrian found himself reminded of his own younger self, the "brash young man" in Cannonball Adderley's band. Pastorius's attitude that night made Zawinul admire the unknown young bassist after all; he asked for a demo tape, which he received at his hotel room the next day. Zawinul listened to some of the tape and realized at once that the young man had considerable technical skills and real potential.[7] He gave him an address to get in touch by mail, and thus began a correspondence between the two. In time, Pastorius sent Zawinul an early rough mix of his solo album.

Pastorius joined Weather Report during the recording sessions for Black Market (1976), and he became a vital part of the band by virtue of the unique qualities of his bass playing, his skills as a composer (and, in time, arranger) and his exuberant showmanship on stage.

Guest appearances

Pastorius guested on many albums by other artists, as for example in 1976 with Ian Hunter of Mott the Hoople fame, on All American Alien Boy, which again featured David Sanborn as well as Aynsley Dunbar. Other recordings included Joni Mitchell's Hejira album, and a solo album by Al Di Meola, both released in 1976. Soon after that, Weather Report bass player Alphonso Johnson left to start his own band. Zawinul invited Pastorius to join the band, where he played alongside Zawinul and Shorter until 1981. During his time with Weather Report, Pastorius made his mark on jazz, notably by being featured on the Grammy Award-nominated Heavy Weather (1977). Not only did this album showcase Pastorius's bass playing and songwriting, he also received a co-producing credit with Zawinul and even played drums on his self-composed "Teen Town". The song was recorded by Marcus Miller on his (1993) studio album, The Sun Don't Lie, as well as composing a song, "Mr. Pastorius" on the same album, in tribute to his friend and colleague.[15]

In the course of his musical career, Pastorius played on dozens of recording sessions for other musicians, both in and out of jazz circles. He also collaborated with jazz figures Flora Purim and Airto Moreira. Pastorius can be heard on Moreira's 1977 release I'm Fine, How Are You? His signature sound is prominent on Purim's 1978 release Everyday Everynight, on which he played the bass melody for a Michel Colombier composition entitled "The Hope", and performed bass and vocals on one of his own compositions, entitled "Las Olas".

Near the end of his career, he guested on low-key releases by jazz artists including guitarist Mike Stern, guitarist Bireli Lagrene and drummer Brian Melvin. In 1985, he recorded an instructional video, Modern Electric Bass, hosted by bassist Jerry Jemmott.

Solo projects

Pastorius left Weather Report in late 1981[7] as he began pursuing his interest in creating a big band solo project named Word of Mouth, one that found its debut aurally on his second solo release, Word of Mouth. This 1981 album also featured guest appearances by several jazz musicians: Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Peter Erskine, harmonica player Toots Thielemans, and Hubert Laws. The album evidenced Pastorius's composing talent alongside the focus on his instrumental performance. It also demonstrated his skills in production and his ability to deal with the studio logistics of a project that was recorded not only on both coasts of the United States, but also overseas: he recorded Thielemans's contributions in Belgium. However, according to Milkowski and company boss Bruce Lundvall, the sessions and production became painfully expensive and the album that emerged was very advanced listening and without appeal to the wider jazz audiences at the time; also, these audiences were moving away from the more loose, improvising and "chamber-like" jazz-rock styles of the seventies towards sounds and stylings that emphasized compressed power soloing and a more commercial and sheeny sound. Warner Bros had signed Pastorius on a very favorable contract due to his groundbreaking playing and his star quality at the time, in the late seventies, but now found themselves with a very difficult-to-sell second album on their hands, and the next year they released Pastorius from his contract. He was not signed by anyone else for quite some time.[7]

On his 30th birthday, December 1, 1981, he held a party at a club in Fort Lauderdale, flew in some of the artists from his Word of Mouth project, and other musicians that included Don Alias, and Michael Brecker. The event was recorded by his friend and engineer Peter Yianilos, who intended it as a birthday gift. The concert remained unreleased until 1995.

Pastorius toured in 1982; his visit to Japan was the highlight, and it was at this time that bizarre tales of Pastorius's deteriorating behavior first surfaced. He shaved his head, painted his face black and threw his bass into Hiroshima Bay at one point.[7] This tour recording was released in Japan as Twins I and Twins II and later condensed for an American release, which was known as Invitation.

In 1982, he recorded a third solo album, which made it as far as some unpolished demo tapes, a steelpans-tinged release entitled Holiday for Pans, which once again showcased him as a composer and producer rather than a performer. He could not find a distributor for the album and the album was never released; however, it has since been widely bootlegged. In 2003, a cut from Holiday for Pans, entitled "Good Morning Anya", was included on Rhino Records' Pastorius anthology Punk Jazz.

Health problems

In his early career Pastorius had avoided alcohol and drugs. With Weather Report he increasingly used alcohol and other drugs,[16] the abuse of which exacerbated his mental issues and led to increasingly erratic and sometimes anti-social behavior.[17]

Pastorius was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in late 1982 following his Word of Mouth tour of Japan, during which his erratic behavior had become an increasing source of concern for his band members.[18] Drummer Peter Erskine's father, Dr. Fred Erskine, suggested that Pastorius was showing signs of the condition and, on his return from the tour, his wife, Ingrid, had Pastorius committed to Holy Cross hospital under the Florida Mental Health Act, where he was diagnosed and prescribed lithium to stabilize his moods.[19]

Pastorius had shown numerous features of the condition long before his initial diagnosis, though they were too mild to diagnose at the time as mental illness; they were regarded instead as eccentricities or character flaws.[20] Hypomania, a psychiatric diagnosis for a milder form of mania characterized by periodic hyperactivity and elevated mood, has been associated with enhanced creativity.[21] According to friends and family, these periods may have been a driving force behind his creation of music.[22]

By 1986, Pastorius's health had further deteriorated and he began living on the streets after being evicted from his New York apartment.[23] In July 1986, following intervention by his then ex-wife Ingrid with the help of his brother Gregory, he was admitted to Bellevue Hospital in New York, where he was prescribed carbamazepine in preference to lithium.[19] He moved back to Fort Lauderdale in December of that year, and again lived on the streets for weeks at a time.[23]

Death

After sneaking onstage at a Carlos Santana concert on September 11, 1987 and being ejected from the premises, Pastorius made his way to the Midnight Bottle Club in Wilton Manors, Florida.[24] After reportedly kicking in a glass door, having been refused entrance to the club, he was engaged in a violent confrontation with the club bouncer, Luc Havan.[25] Pastorius was hospitalized for multiple facial fractures and injuries to his right eye and left arm and fell into a coma.[26]

Initially, there were encouraging signs that he would come out of the coma and recover, but they soon faded. A massive brain hemorrhage a few days later led to brain death. Pastorius died on September 21, 1987, aged 35, at Broward General Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale and was buried at Our Lady Queen of Heaven Cemetery in North Lauderdale.[27]

In the wake of Pastorius's death, Havan was charged with second degree murder but later pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Because he had no prior convictions, and recognizing time served while waiting for the verdict, the court sentenced him to 22 months in prison and five years' probation. After four months in prison, he was paroled for good behavior.[28]

Musical style

Pastorius was noted for his virtuosic bass lines which combined Afro-Cuban rhythms, inspired by the likes of Cachao López, with R&B to create 16th-note funk lines syncopated with ghost notes. He played these with a floating thumb technique on the right hand, anchoring on the bridge pickup while playing on the E and A strings and muting the E string with his thumb while playing on higher strings. Examples include "Come On, Come Over" from the album Jaco Pastorius and "The Chicken" from The Birthday Concert.

|

Jaco Pastorius, "Portrait of Tracy" from Jaco Pastorius (1976)

Sample from "Portrait of Tracy" with extensive use of harmonics. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

He was also known for popularizing the fretless electric bass, with which he was able to achieve an almost horn-like tone while playing in the upper register. Examples include the melodies on "Birdland" from the Weather Report album Heavy Weather and "Three Views of a Secret" from the Weather Report album Night Passage, as well as his line on the Joni Mitchell song "Refuge of the Road" from her album Hejira.

One of Pastorius's innovations was in the use of harmonics, which isolate the overtones of a note by muting the string at a harmonic node, resulting in a much higher note than would otherwise be sounded. He used this technique extensively to construct melodies, such as in his composition Portrait of Tracy from his eponymous album, and the melody from the popular Weather Report tune "Birdland," which is often mistaken for guitar.

Equipment

Basses and strings

Jaco is most frequently associated with the 1962 Fender Jazz Bass nicknamed the Bass of Doom, which had its frets removed. Pastorius claimed to have removed the frets himself[29] but later said he had bought it with the frets already removed. Pastorius finished the fretboard with marine epoxy (Pettit's PolyPoxy) to protect the wood from the roundwound Rotosound Swing 66 strings he used.[29] The Bass of Doom was heavily worn and was repaired several times, most notably in the mid-1980s when the bass was smashed into a number of pieces and rebuilt with figured maple veneers added to the front and back to improve the structural integrity.[30]

Though he played both fretted and fretless, he preferred the fretless, because he felt frets were a hindrance, once calling them "speed bumps". However, he said in the instructional video that he never practiced with the fretless because the strings "eat the neck up".

In 1986, shortly before he entered Bellevue hospital, Jaco's Fender bass was stolen. In 1993, the bass was in the hands of a New York City music shop. In 2008, it was subsequently acquired by Robert Trujillo, bassist with Metallica. Although Trujillo currently owns the instrument, the Metallica bassist agreed in writing to relinquish the instrument to the family at any time for the same purchase price.[31]

Amplification and effects

Jaco Pastorius used the "Variamp" EQ (equalization) controls on his two Acoustic 360 amplifiers[32] (made by the Acoustic Control Corporation of Van Nuys, California) to boost the midrange frequencies, thus accentuating the natural growling tone of his fretless passive Fender Jazz Bass and roundwound string combination. He also controlled his tone color with a rackmount MXR digital delay unit that fed a second Acoustic amp rig.

At times, he used Hartke cabinets during the final three years of his life because of the bright character of aluminum speaker cones (as opposed to paper speaker cones). These provided a bright, clear sound. He typically used the delay in a chorus-like mode, providing a shimmering stereo doubling effect. He often used the fuzz control built in on the Acoustic 361. For the bass solo "Slang" on Weather Report's live album 8:30 (1979), Pastorius used the MXR digital delay to layer and loop a chordal figure and then soloed over it; the same technique, with a looped bass riff, can be seen during his solo spot on the Joni Mitchell concert video Shadows and Light.

Legacy

He has been called "arguably the most important and ground-breaking electric bassist in history" and "perhaps the most influential electric bassist today".[33][34] William C. Banfield, director of Africana Studies, Music and Society at Berklee College, describes Jaco as one of the few original American virtuosos who defined a musical movement, alongside Jimi Hendrix, Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Christian, Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Sarah Vaughan, Bill Evans, Charles Mingus and Wes Montgomery.[35]

Awards and tributes

Pastorius received two Grammy Award nominations in 1977 for his self-titled debut album, including Best Jazz Performance by a Group and Best Jazz Performance by a Soloist for "Donna Lee".[36] He received another nomination in 1978, Best Jazz Performance by a Soloist, for his work on Weather Report's Heavy Weather.[37] In 1988, following his death, Jaco was elected by readers' poll for inclusion in the Down Beat Hall of Fame, the second bassist honored in this way. To date, only seven bassists have been inducted, the others being Jimmy Blanton, Ray Brown, Ron Carter, Charles Mingus, Charlie Haden and Milt Hinton.[38]

Numerous artists have recorded tributes to Jaco, including the Pat Metheny Group track "Jaco" on their album Pat Metheny Group (1978);[39] the Marcus Miller composition "Mr. Pastorius" on Miles Davis's album Amandla;[40] Victor Bailey (who replaced Jaco in Weather Report)'s cover of "Continuum" on his Low Blow album; several tracks on Victor Wooten and Steve Bailey's Bass Extremes album; John McLaughlin's "For Jaco" on his album Industrial Zen (2006) among others.

Since 1997, an annual birthday event takes place around December 1 in South Florida, hosted by his sons Julius and Felix Pastorius.

On December 2, 2007, the day after his birthday, a concert called "20th Anniversary Tribute to Jaco Pastorius" was held at The Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, featuring performances by the award-winning Jaco Pastorius Big Band with special guest appearances by Peter Erskine, Randy Brecker, Bob Mintzer, David Bargeron, Jimmy Haslip, Gerald Veasley, Pastorius's sons John and Julius Pastorius, Pastorius's daughter Mary Pastorius, Ira Sullivan, Bobby Thomas, Jr., and Dana Paul. Also shown were exclusive home movies and rare concert footage as well as video appearances by Pat Metheny, Joni Mitchell, and other luminaries from Pastorius's life. Almost 20 years after his death, Fender released the Jaco Pastorius Jazz Bass, a fretless instrument in its Artist Series.

On December 1, 2008, on his birthday, the park in Oakland Park's new downtown redevelopment was formally named 'Jaco Pastorius Park' in honor of the area's former resident.[41]

Discography

See also

- Jaco, a 2014 documentary film.

- List of jazz bassists

Notes

- ↑ Harrison, Angus (2015-03-06). "Jaco Pastorius Is the Most Important Musician You Might Have Never Heard Of | NOISEY". Noisey.vice.com. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- 1 2 3 Jaco Pastorius official website

- ↑ Ingrid's Jaco Cyber Nest; FAQ

- ↑ Haapala Family Genealogical Research by Cynthia Pannell

- ↑ Ingrid's Jaco Cybernest; FAQ

- ↑ GQ, 1988

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Milkowski, 2005

- ↑ BBC radio 3 profile; Jaco Pastorius official website biography

- ↑ Rich Franks; Jaco Pastorius official website biography

- ↑ Bob Bobbing (2007), Jaco and the upright bass; Jaco Pastorius Official Website biography

- ↑ Bobby Colomby

- ↑ AllMusic; Jaco Pastorius credits

- ↑ Zawinul, Josef on the Portrait of Jaco cd

- ↑ GQ

- ↑ "The Sun Don't Lie". Album review. Allmusic. 2016. pp. Marcus Miller review. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Milkowski, 2005; Flynn

- ↑ Torn Moon 1987; United Press 1987

- ↑ Mary Pastorius; Daddy, just Daddy to me

- 1 2 Ingrid's Jaco Cybernest; Mind II

- ↑ Milkowski, 2005; Grayson, 2003

- ↑ Santosa, 2006; Redfield 1993

- ↑ Ingrid's Jaco Cybernest; Ken Gemmer's Insight; Torn Moon (1987)

- 1 2 Torn Moon (1987)

- ↑ Stanton, p.195

- ↑ Jeff Stratton (November 30, 2006). "browardpalmbeach.com". browardpalmbeach.com. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- ↑ "Noted Musician Listed As Critical After Altercation". Sun Sentinel. September 16, 1987. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ↑ Stanton

- ↑ Broward Palm Beach News (2006)

- 1 2 Rosen, 1978

- ↑ Jisi, Chris (March 2008), "Jaco's Bass found", Bass Player

- ↑ Robert-trujillo-helps-pastorius-family-reclaim-jacos-bass-of-doom

- ↑ "Acoustic 360 amplifiers". Acoustic.homeunix.net. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- ↑ Belew, Adrian (1986), New Directions in Modern Guitar, Hal Leonard Publications

- ↑ Starr, Eric; Starr, Nelson (2008), The Everything Bass Guitar Book, F&W Publications Inc

- ↑ Banfield, William C (2009), Cultural Codes: Makings of a Black Music Philosophy, p. 161

- ↑ "Grammy Awards 1977", Awards and Shows, retrieved July 1, 2013

- ↑ "Grammy Awards 1978", Awards and Shows, retrieved July 1, 2013

- ↑ "DownBeat Hall of Fame", DownBeat, retrieved July 1, 2013

- ↑ Metheny, Pat. Pat Metheny Songbook. Appendix: Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 439. ISBN 0-634-00796-3.

- ↑ Perspectives on Jaco; Cole p297

- ↑ Oakland Park Main Street

References

- "Jaco Pastorius official website". Jacopastorius.co.uk. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- "Jaco Pastorius: 20 Years Later". NPR. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- United Press (September 22, 1987). "Jazz Musician Jaco Pastorius Dies". JoniMitchell.com. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "Jaco Pastorius credits". Allmusic. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- Billboard (October 26, 2002). "Come on, come over". Jazz Notes. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- "Oakland Park to cut ribbon for Jaco Pastorius Park on December 1st" (PDF). oaklandparkmainstreet.com. October 31, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 7, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Torn Moon (September 20, 1987). "Dark Days for a Jazz Genius". Miami Herald. JoniMitchell.com. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "Radio 3 Jazz Profiles: Jaco Pastorius". BBC. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- "Jaco Incorporated". New Times. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Robert Trujillo Assists Pastorius Family in Recovering the Infamous Bass of Doom". Metallica.com. May 28, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- Bobbing, Bob (2008). "Bill Milkowski's Jaco Biography". JacoPastorius.com forums. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Bobbing, Bob (2007). "Jaco and the upright bass". JacoPastorius.com forums.

- Cole, George (2005). The Last Miles: The music of Miles Davis, 1980–1991. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-03260-0.

- Colomby, Bobby (2005). "Bobby Columby Story....True?". JacoPastorius.com forums.

- Currin, Grayson (August 6, 2003). "Continuum". IndyWeek.com. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- Flynn, Mike. "Pat Metheny – A man and machine in perfect harmony". munkio.com. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- Franks, Trane. "Untitled". threeviews.com. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Gemmer, Ken. "Ken Gemmer's Insight". jacop.net. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- Ginell, Richard S. All Music Jaco Pastorius biography. Allmusic. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- Jamison, Kay Redfield (1993). Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Creative Temperament. New York: The Free Press.

- Jisi, Chris (March 2008). "Jaco's 1962 Fender Jazz Bass "Bass of Doom" Found!". Bass Player Online. New Bay Media, LLC. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- Jordan, Pat (1988). "Who Killed Jaco Pastorius?". GQ (May). Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- Kelman, John. "Brian Bromberg – "Jaco" – Jazz Review". indiejazz.com. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Metheny, Pat (2000). "The Life and Music of Jaco Pastorious". Liner Notes to Jaco's eponymous debut album. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- Miller, Marcus (2002). "Perspectives on Jaco". JacoPastorius.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Milkowsi, Bill (1984). "Bass Revolutionary: Jaco Pastorius Interview". Guitar Player (August 1984).

- Milkowski, Bill (1995). Jaco: the extraordinary and tragic life of Jaco Pastorius (1st ed.). Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-361-1.

- Milkowski, Bill (2005). Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius (2nd ed.). Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-361-1.

- Pastorius, Ingrid. Frequently asked questions. Ingrid's Jaco Cyber Nest. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- Pastorius, Ingrid. "Book". Ingrid's Jaco Cybernest. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Pastorius, Ingrid. "Book Corrections". Ingrid's Jaco Cybernest. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Pastorius, Ingrid. "Mind II". Ingrid's Jaco Cybernest. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- Pastorius, Mary (1994). "Daddy, just Daddy to me". jacopastorius.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Prasad, Anil (1997). "Joe Zawinul, Man of the people". Innerviews. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- Rosen, Steve (1978). "Portrait of Jaco". JacoPastorius.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- Santosa, C.M.; Strong, C.M.; Nowakowska, C.; Wang, P.W.; Rennicke, C.M.; Ketter, T.A. (2006). "Enhanced creativity in bipolar disorder patients: A controlled study.". Journal of Affective Disorders. 100 (1–3): 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.013. PMID 17126406.

- Salloum, I.M.; Thase, M.E. (2000). "Impact of substance abuse on the course and treatment of bipolar disorder". Bipolar Disorders. 2 (3 Pt 2): 269–80. doi:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20308.x. PMID 11249805.

- Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7434-6330-7.

External links

- Jaco Pastorius – official site

- Jaco Pastorius discography at Discogs

- Jaco Pastorius at Find a Grave

- Jaco Pastorius discography at MusicBrainz

- Jaco Pastorius at Myspace

- Jacob Pastorius profile at NNDB

- Pastorius family site

- Jaco Pastorius 1978 radio interview

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jaco Pastorius. |