Atheroma

| Atheroma | |

|---|---|

|

Atherosclerotic plaque from a carotid endarterectomy specimen. This shows the bifurcation of the common into the internal and external carotid arteries. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | cardiology |

| ICD-10 | I70.9 |

| ICD-9-CM | 440 |

| DiseasesDB | 1039 |

| MeSH | C14.907.137.126.307 |

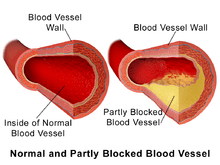

An atheroma (plural: atheromata or atheromas) is an accumulation of degenerative material in the tunica intima (inner layer) of artery walls. The material consists of (mostly) macrophage cells,[1][2] or debris, containing lipids (cholesterol and fatty acids), calcium and a variable amount of fibrous connective tissue. The accumulated material forms a swelling in the artery wall, which may intrude into the channel of the artery, narrowing it and restricting blood flow. Atheroma occurs in atherosclerosis, which is one of the three subtypes of arteriosclerosis (which are atherosclerosis, Monckeberg's arteriosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis).[3]

In the context of heart or artery matters, atheromata are commonly referred to as atheromatous plaques. It is an unhealthy condition found in most humans.[4]

Veins do not develop atheromata, unless surgically moved to function as an artery, as in bypass surgery. The accumulation (swelling) is always in the tunica intima, between the endothelium lining and the smooth muscle tunica media (middle layer) of the artery wall. While the early stages, based on gross appearance, have traditionally been termed fatty streaks by pathologists, they are not composed of fat cells, i.e. adipose cells, but of accumulations of white blood cells, especially macrophages, that have taken up oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL). After they accumulate large amounts of cytoplasmic membranes (with associated high cholesterol content) they are called foam cells. When foam cells die, their contents are released, which attracts more macrophages and creates an extracellular lipid core near the center to inner surface of each atherosclerotic plaque. Conversely, the outer, older portions of the plaque become more calcified, less metabolically active and more physically stiff over time.

Signs and symptoms

For most people, the first symptoms result from atheroma progression within the heart arteries, most commonly resulting in a heart attack and ensuing debility. However, the heart arteries, because (a) they are small (from about 5 mm down to microscopic), (b) they are hidden deep within the chest and (c) they never stop moving, have been a difficult target organ to track, especially clinically in individuals who are still asymptomatic. Additionally, all mass-applied clinical strategies focus on both (a) minimal cost and (b) the overall safety of the procedure. Therefore, existing diagnostic strategies for detecting atheroma and tracking response to treatment have been extremely limited. The methods most commonly relied upon, patient symptoms and cardiac stress testing, do not detect any symptoms of the problem until atheromatous disease is very advanced because arteries enlarge, not constrict in response to increasing atheroma.[5] It is plaque ruptures, showing debris & clots which obstruct blood flow downstream, sometime also locally (as seen on angiograms), which reduce/stop blood flow. Yet these events occur suddenly & are not revealed in advance by either stress testing, stress tests or angiograms.

History of research

In developed countries, with improved public health, infection control and increasing life spans, atheroma processes have become an increasingly important problem and burden for society. Atheromata continue to be the primary underlying basis for disability and death, despite a trend for gradual improvement since the early 1960s (adjusted for patient age). Thus, increasing efforts towards better understanding, treating and preventing the problem are continuing to evolve.

According to United States data, 2004, for about 65% of men and 47% of women, the first symptom of cardiovascular disease is myocardial infarction (heart attack) or sudden death (death within one hour of symptom onset.)

A significant proportion of artery flow-disrupting events occur at locations with less than 50% lumenal narrowing. Cardiac stress testing, traditionally the most commonly performed noninvasive testing method for blood flow limitations, generally only detects lumen narrowing of ~75% or greater, although some physicians advocate nuclear stress methods that can sometimes detect as little as 50%.

The sudden nature of the complications of pre-existing atheroma, vulnerable plaque (non-occlusive or soft plaque), have led, since the 1950s, to the development of intensive care units and complex medical and surgical interventions. Angiography and later cardiac stress testing was begun to either visualize or indirectly detect stenosis. Next came bypass surgery, to plumb transplanted veins, sometimes arteries, around the stenoses and more recently angioplasty, now including stents, most recently drug coated stents, to stretch the stenoses more open.

Yet despite these medical advances, with success in reducing the symptoms of angina and reduced blood flow, atheroma rupture events remain the major problem and still sometimes result in sudden disability and death despite even the most rapid, massive and skilled medical and surgical intervention available anywhere today. According to some clinical trials, bypass surgery and angioplasty procedures have had at best a minimal effect, if any, on improving overall survival. Typically mortality of bypass operations is between 1 and 4%, of angioplasty between 1 and 1.5%.

Additionally, these vascular interventions are often done only after an individual is symptomatic, often already partially disabled, as a result of the disease. It is also clear that both angioplasty and bypass interventions do not prevent future heart attack.

The older methods for understanding atheroma, dating to before World War II, relied on autopsy data. Autopsy data has long shown initiation of fatty streaks in later childhood[6] with slow asymptomatic progression over decades.[5]

One way to see atheroma is the very invasive and costly IVUS ultrasound technology; it gives us the precise volume of the inside intima plus the central media layers of about 2.5 cm (1 in) of artery length. Unfortunately, it gives no information about the structural strength of the artery. Angiography does not visualize atheroma; it only makes the blood flow within blood vessels visible. Alternative methods that are non or less physically invasive and less expensive per individual test have been used and are continuing to be developed, such as those using computed tomography (CT; led by the electron beam tomography form, given its greater speed) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The most promising since the early 1990s has been EBT, detecting calcification within the atheroma before most individuals start having clinically recognized symptoms and debility. Interestingly, statin therapy (to lower cholesterol) does not slow the speed of calcification as determined by CT scan. MRI coronary vessel wall imaging, although currently limited to research studies, has demonstrated the ability to detect vessel wall thickening in asymptomatic high risk individuals.[7] As a non-invasive, ionising radiation free technique, MRI based techniques could have future uses in monitoring disease progression and regression. Most visualization techniques are used in research, they are not widely available to most patients, have significant technical limitations, have not been widely accepted and generally are not covered by medical insurance carriers.

From human clinical trials, it has become increasingly evident that a more effective focus of treatment is slowing, stopping and even partially reversing the atheroma growth process. There are several prospective epidemiologic studies including the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), which have supported a direct correlation of Carotid Intima-media thickness (CIMT) with myocardial infarction and stroke risk in patients without cardiovascular disease history. The ARIC Study was conducted in 15,792 individuals between 5 and 65 years of age in 4 different regions of the US between 1987 and 1989. The baseline CIMT was measured and measurements were repeated at 4- to 7-year intervals by carotid B mode ultrasonography in this study. An increase in CIMT was correlated with an increased risk for CAD. The CHS was initiated in 1988, and the relationship of CIMT with risk of myocardial infarction and stroke was investigated in 4,476 subjects ≤65 years of age. At the end of approximately 6 years of follow-up, CIMT measurements were correlated with cardiovascular events.

Paroi artérielle et Risque Cardiovasculaire in Asia Africa/Middle East and Latin America (PARC-AALA) is another important large-scale study, in which 79 centers from countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America participated, and the distribution of CIMT according to different ethnic groups and its association with the Framingham cardiovascular score was investigated. Multi-linear regression analysis revealed that an increased Framingham cardiovascular score was associated with CIMT, and carotid plaque independent of geographic differences.

Cahn et al. prospectively followed-up 152 patients with coronary artery disease for 6–11 months by carotid artery ultrasonography and noted 22 vascular events (myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, stroke, and coronary angioplasty) within this time period. They concluded that carotid atherosclerosis measured by this non-interventional method has prognostic significance in coronary artery patients.

In the Rotterdam Study, Bots et al. followed 7,983 patients >55 years of age for a mean period of 4.6 years, and reported 194 incident myocardial infarctions within this period. CIMT was significantly higher in the myocardial infarction group compared to the other group. Demircan et al. found that the CIMT of patients with acute coronary syndrome were significantly increased compared to patients with stable angina pectoris.

It has been reported in another study that a maximal CIMT value of 0.956 mm had 85.7% sensitivity and 85.1% specificity to predict angiographic CAD. The study group consisted of patients admitted to the cardiology outpatient clinic with symptoms of stable angina pectoris. The study showed CIMT was higher in patients with significant CAD than in patients with non-critical coronary lesions. Regression analysis revealed that thickening of the mean intima-media complex more than 1.0 was predictive of significant CAD our patients. There was incremental significant increase in CIMT with the number coronary vessel involved. In accordance with the literature, it was found that CIMT was significantly higher in the presence of CAD. Furthermore, CIMT was increased as the number of involved vessels increased and the highest CIMT values were noted in patients with left main coronary involvement. However, human clinical trials have been slow to provide clinical & medical evidence, partly because the asymptomatic nature of atheromata make them especially difficult to study. Promising results are found using carotid intima-media thickness scanning (CIMT can be measured by B-mode ultrasonography), B-vitamins that reduce a protein corrosive, homocysteine and that reduce neck carotid artery plaque volume and thickness, and stroke, even in late-stage disease.

Additionally, understanding what drives atheroma development is complex with multiple factors involved, only some of which, such as lipoproteins, more importantly lipoprotein subclass analysis, blood sugar levels and hypertension are best known and researched. More recently, some of the complex immune system patterns that promote, or inhibit, the inherent inflammatory macrophage triggering processes involved in atheroma progression are slowly being better elucidated in animal models of atherosclerosis.

Disease progression

The healthy epicardial coronary artery consists of three layers, the intima, media, and adventitia.[8][9] Atheroma and changes in the artery wall usually result in small aneurysms (enlargements) just large enough to compensate for the extra wall thickness with no change in the lumen diameter. However, eventually, typically as a result of rupture of vulnerable plaques and clots within the lumen over the plaque, stenosis (narrowing) of the vessel develops in some areas. Less frequently, the artery enlarges so much that a gross aneurysmal enlargement of the artery results. All three results are often observed, at different locations, within the same individual.

Stenosis and closure

Over time, atheromata usually progress in size and thickness and induce the surrounding muscular central region (the media) of the artery to stretch out, termed remodeling, typically just enough to compensate for their size such that the caliber of the artery opening lumen) remains unchanged until typically over 50% of the artery wall cross-sectional area consists of atheromatous tissue "Compensatory Enlargement of Human Atherosclerotic Coronary Arteries"New England Journal of Medicine, 05/28/1987.

If the muscular wall enlargement eventually fails to keep up with the enlargement of the atheroma volume, or a clot forms and organizes over the plaque, then the lumen of the artery becomes narrowed as a result of repeated ruptures, clots & fibrosis over the tissues separating the atheroma from the blood stream. This narrowing becomes more common after decades of living, increasingly more common after people are in their 30s to 40s.

The endothelium (the cell monolayer on the inside of the vessel) and covering tissue, termed fibrous cap, separate atheroma from the blood in the lumen. If a rupture (see vulnerable plaque) of the endothelium and fibrous cap occurs, then both (a) a shower of debris from the plaque combined with (b) a platelet and clotting response (to both the debies and at the rupture site) occurs within fractions of a second.

The rupture results in both (a) a shower of debris occluding smaller downstream vessels (debris larger than 5 microns are too large to pass through capillaries)) combined with (b) platelet and clot accumulation over the rupture (an injury/repair response) resulting in narrowing, sometimes closure, of the lumen.

Downstream tissue damage occurs due to (a) closure of downstream microvascular and/or (b) closure of the lumen at the rupture, both resulting in loss of blood flow to downstream capillary microvasulature. This is the principal mechanism of myocardial infarction, stroke or other related cardiovascular disease problems.

While clots at the rupture site typically shrink in volume over time, some of the clot may become organized into fibrotic tissue resulting in narrowing of the artery lumen; the narrowings sometimes seen on angiography examinations, if severe enough. Since angiography methods can only reveal larger lumens, typically >>200 microns, angiography after a cardiovascular event commonly does not reveal what happened.

Artery enlargement

If the muscular wall enlargement is overdone over time, then a gross enlargement of the artery results, usually over decades of living. This is a less common outcome. Atheroma within aneurysmal enlargement (vessel bulging) can also rupture and shower debris of atheroma and clot downstream. If the arterial enlargement continues to 2 to 3 times the usual diameter, the walls often become weak enough that with just the stress of the pulse, a loss of wall integrity may occur leading to sudden hemorrhage (bleeding), major symptoms and debility; often rapid death. The main stimulus for aneurysm formation is pressure atrophy of the structural support of the muscle layers. The main structural proteins are collagen and elastin. This causes thinning and the wall balloons allowing gross enlargement to occur, as is common in the abdominal region of the aorta.

Diagnosis

Because artery walls enlarge at locations with atheroma,[5] detecting atheroma before death and autopsy has long been problematic at best. Most methods have focused on the openings of arteries; highly relevant, yet totally miss the atheroma within artery walls.

Historically, arterial wall fixation, staining and thin section has been the gold standard for detection and description of atheroma, after death and autopsy. With special stains and examination, micro calcifications[10] can be detected, typically within smooth muscle cells of the arterial media near the fatty streaks within a year or two of fatty streaks forming.

Interventional and non-interventional methods to detect atherosclerosis, specifically vulnerable plaque (non-occlusive or soft plaque), are widely used in research and clinical practice today.

Carotid Intima-media thickness Scan (CIMT can be measured by B-mode ultrasonography) measurement has been recommended by the American Heart Association as the most useful method to identify atherosclerosis and may now very well be the gold standard for detection.

IVUS is the current most sensitive method detecting and measuring more advanced atheroma within living individuals, though it is typically not used until decades after atheroma begin forming due to cost and body invasiveness.

CT scans using state of the art higher resolution spiral, or the higher speed EBT, machines have been the most effective method for detecting calcification present in plaque. However, the atheroma have to be advanced enough to have relatively large areas of calcification within them to create large enough regions of ~130 Hounsfield units which a CT scanner's software can recognize as distinct from the other surrounding tissues. Typically, such regions start occurring within the heart arteries about 2–3 decades after atheroma start developing. Hence the detection of much smaller plaques than previously possible is being developed by some companies, such as Image Analysis. The presence of smaller, spotty plaques may actually be more dangerous for progressing to acute myocardial infarction.[11]

Arterial ultrasound, especially of the carotid arteries, with measurement of the thickness of the artery wall, offers a way to partially track the disease progression. As of 2006, the thickness, commonly referred to as IMT for intimal-medial thickness, is not measured clinically though it has been used by some researchers since the mid-1990s to track changes in arterial walls. Traditionally, clinical carotid ultrasounds have only estimated the degree of blood lumen restriction, stenosis, a result of very advanced disease. The National Institute of Health did a five-year $5 million study, headed by medical researcher Kenneth Ouriel, to study intravascular ultrasound techniques regarding atherosclerotic plaque.[12] More progressive clinicians have begun using IMT measurement as a way to quantify and track disease progression or stability within individual patients.

Angiography, since the 1960s, has been the traditional way of evaluating for atheroma. However, angiography is only motion or still images of dye mixed with the blood with the arterial lumen and never show atheroma; the wall of arteries, including atheroma with the arterial wall remain invisible. The limited exception to this rule is that with very advanced atheroma, with extensive calcification within the wall, a halo-like ring of radiodensity can be seen in most older humans, especially when arterial lumens are visualized end-on. On cine-floro, cardiologists and radiologists typically look for these calcification shadows to recognize arteries before they inject any contrast agent during angiograms.

Proxy measurement

Since the 1990s, both small clinical and several larger-scale pharmaceutical trials have used carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) as a surrogate endpoint for evaluating the regression and/or progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Many studies have documented the relationship between the carotid intima-media thickness and the presence and severity of atherosclerosis. In 2003, the European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology recommended the use of IMT measurements in high-risk patients to help identify target organ damage not revealed by other exams such as the electrocardiogram.

Though carotid intima-media thickness seems to be strongly associated with atherosclerosis, not all of the processes of thickening of the intima-media are due to atherosclerosis. Intimal thickening is in fact a complex process, depending on a variety of factors, not necessarily related to atherosclerosis. Local hemodynamics play an important role, higher blood pressure and changes in shear stress being potential causes of intimal thickening. Changes in shear stress and blood pressure may cause a local delay in lumenal transportation of potentially atherogenic particles, which favors the penetration of particles into the arterial wall and consequent plaque formation. However non-atherosclerotic reactions may also exist, as in intimal hyperplasia and intimal fibrocellular hypertrophy, two different compensatory reactions of the arterial wall to changes in shear stress, which also consist in thickening of the arterial wall. In some cases, more than one of these reactions may be present, and indeed as all of these are associated to particular flow conditions, they are often found in common areas, such as the inflow side of branches, the inner curvature at bends and opposite the flow divider at bifurcations. However, changes in the IMT above thresholds of around 900 μm almost certainly are indicative of an atherosclerotic pathology.

Mechanisms such as these may explain, at least in part, why the carotid artery seems to be a preferential site for analyzing the relation between wall thickness and atherosclerosis. In general, wall thickening may be in the intimal layer or in the muscular medial layer. As the carotid artery is an elastic artery, the muscular media is relatively small. Hence, thickening of the carotid arterial wall is due essentially to intimal thickening. In muscular arteries wall thickening may imply instead (or also) a thickening of the medial wall. Whether or not wall thickening in the carotid artery and the femoral artery (or other muscular arteries) have the same meaning is as yet uncertain. Several studies seem to suggest that the mechanisms underlying their evolution may at least in part differ, with consequently possibly different clinical implications.

Another issue to consider, once the choice to examine the carotid artery has been defined, is on which segment of the carotid artery to perform the measurement. Often, the measurement of the IMT is measured in three tracts: in the common carotid, at one or two cm from the flow divider, at the bifurcation and in the internal carotid artery.

From an academic standpoint, the region to select for IMT measurement is still an object of study. IMT measurements of the deep wall by ultrasound are generally more reliable than measurements performed on the outer wall. This difference in the accuracy of near and far wall measurements may be a problem, as some studies have used both measurements to quantify the IMT.

A practical approach to tracking disease presence and progression on any given individual is to select and track those regions with the greatest thickness, i.e. greatest disease burden, as opposed to arbitrarily selecting a particular segment in which the individual may not have much pathology.

Classification of lesions

- Type I: Isolated macrophage foam cells[8][13]

- Type II: Multiple foam cell layers[8][13]

- Type III: Preatheroma, intermediate lesion[8][13]

- Type IV: Atheroma[8][13]

- Type V: Fibroatheroma[8][13]

- Type VI: Fissured, ulcerated, hemorrhagic, thrombotic lesion[8][13]

- Type VII: Calcific lesion[8][13]

- Type VIII: Fibrotic lesion[8][13]

Treatment

Many approaches have been promoted as methods to reduce atheroma progression:

- eating a diet of raw fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, berries, and grains;

- consuming foods containing omega-3 fatty acids such as fish, fish-derived supplements, as well as flax seed oil, borage oil, and other non-animal-based oils;

- abdominal fat reduction;

- aerobic exercise;

- inhibitors of cholesterol synthesis (known as statins);

- low normal blood glucose levels (glycosylated hemoglobin, also called HbA1c);

- micronutrient (vitamins, potassium, and magnesium) consumption;

- maintaining normal, or healthy, blood pressure levels;

- aspirin supplement

- cyclodextrin can solubilize cholesterol, removing it from plaques[14]

Put simply, take steps to live a healthy, sustainable lifestyle.

See also

- Angiogram

- ApoA-1 Milano

- Atherosclerosis

- Atherothrombosis

- Coronary circulation

- Coronary catheterization

- EBT

- Hemorheologic-Hemodynamic Theory of Atherosclerosis

- Lipoprotein

- LDL, HDL, IDL and VLDL

References

- ↑ Hotamisligil GS (2010). "Endoplasmic reticulum stress and atherosclerosis". Nature Medicine. 16 (4): 396–9. doi:10.1038/nm0410-396. PMC 2897068

. PMID 20376052.

. PMID 20376052. - ↑ Oh J, Riek AE, Weng S, Petty M, Kim D, Colonna M, Cella M, Bernal-Mizrachi C (2012). "Endoplasmic reticulum stress controls M2 macrophage differentiation and foam cell formation". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (15): 11629–41. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.338673. PMC 3320912

. PMID 22356914.

. PMID 22356914. - ↑ http://www.mercksource.com[]

- ↑ Lusis AJ (September 2000). "Atherosclerosis". Nature. 407 (6801): 233–41. doi:10.1038/35025203. PMC 2826222

. PMID 11001066.

. PMID 11001066. - 1 2 3 4 http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM198705283162204

- ↑ https://www.google.com/search?q=fatty+streaks+in+later+childhood

- ↑ Kim 2002, Circulation

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis at eMedicine

- ↑ Waller BF, Orr CM, Slack JD, Pinkerton CA, Van Tassel J, Peters T (June 1992). "Anatomy, histology, and pathology of coronary arteries: a review relevant to new interventional and imaging techniques—Part I". Clin Cardiol. 15 (6): 451–7. doi:10.1002/clc.4960150613. PMID 1617826.

- ↑ Roijers RB, Debernardi N, Cleutjens JP, Schurgers LJ, Mutsaers PH, van der Vusse GJ (2011). "Microcalcifications in early intimal lesions of atherosclerotic human coronary arteries". Am. J. Pathol. 178: 2879–87. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.004. PMC 3124018

. PMID 21531376.

. PMID 21531376. - ↑ Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, et al. (November 2004). "Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study". Circulation. 110 (22): 3424–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000148131.41425.E9. PMID 15557374.

- ↑ "Dr. Kenneth Ouriel (biography)" (PDF). New York-Presbyterian Hospital. 2009-09-22. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stary, Herbert C. (2003). Atlas of atherosclerosis: progression and regression. Parthenon Pub. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84214-153-3.

- ↑ Zimmer Sebastian; Grebe Alena; Bakke Siril S.; et al. "Cyclodextrin promotes atherosclerosis regression via macrophage reprogramming". Science Translational Medicine. 8 (333): 333–50. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6100.

Further reading

- Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. (July 1990). "Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial". Lancet. 336 (8708): 129–33. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)91656-U. PMID 1973470.

- Gould KL, Ornish D, Scherwitz L, et al. (September 1995). "Changes in myocardial perfusion abnormalities by positron emission tomography after long-term, intense risk factor modification". JAMA. 274 (11): 894–901. doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03530110056036. PMID 7674504.

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. (December 1998). "Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease". JAMA. 280 (23): 2001–7. doi:10.1001/jama.280.23.2001. PMID 9863851.

- Ornish D (November 1998). "Avoiding revascularization with lifestyle changes: The Multicenter Lifestyle Demonstration Project". The American Journal of Cardiology. 82 (10B): 72T–76T. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00744-9. PMID 9860380.

- Dod HS, Bhardwaj R, Sajja V, et al. (February 2010). "Effect of intensive lifestyle changes on endothelial function and on inflammatory markers of atherosclerosis". The American Journal of Cardiology. 105 (3): 362–7. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.038. PMID 20102949.

- Silberman A, Banthia R, Estay IS, et al. (2010). "The effectiveness and efficacy of an intensive cardiac rehabilitation program in 24 sites". American Journal of Health Promotion. 24 (4): 260–6. doi:10.4278/ajhp.24.4.arb. PMID 20232608.

- Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ (May 1987). "Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries". The New England Journal of Medicine. 316 (22): 1371–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM198705283162204. PMID 3574413.

- Sparks RA (July 1976). "Letter: Fomites in vaginitis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 115 (1): 19. PMC 1878585

. PMID 1277053.

. PMID 1277053.