Ma'ale Adumim

Ma'ale Adumim

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | ||

| • ISO 259 | Maˁle ʔadummim | |

| • Also spelled | Ma'ale Adummim (official) | |

| ||

| ||

Ma'ale Adumim | ||

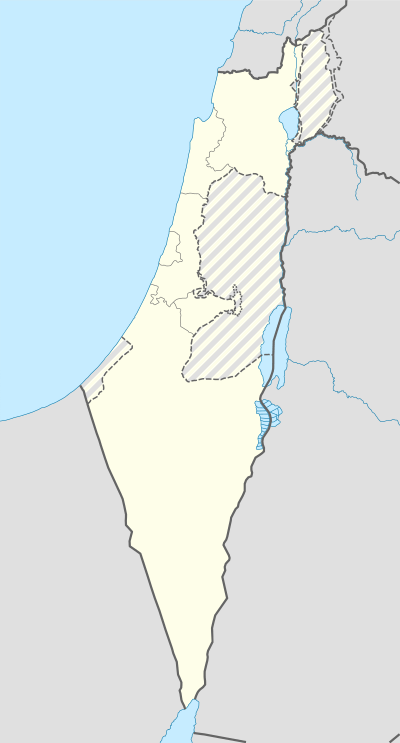

| Coordinates: 31°46′30″N 35°17′53″E / 31.77500°N 35.29806°ECoordinates: 31°46′30″N 35°17′53″E / 31.77500°N 35.29806°E | ||

| Region | West Bank | |

| District | Judea and Samaria Area | |

| Founded | September 21, 1975 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | City (from 1991) | |

| • Mayor | Benny Kashriel | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 49,177 dunams (49.177 km2 or 18.987 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015)[1] | ||

| • Total | 37,525 | |

| Name meaning | Red ascent | |

Ma'ale Adumim (Hebrew: מַעֲלֵה אֲדֻמִּים, Arabic: معالي أدوميم) is an urban Israeli settlement and a city in the West Bank, seven kilometers (4.3 miles) from Jerusalem.[2] Ma'ale Adumim achieved city status in 1991. In 2015 its population was 37,525. Located along Highway 1, which connects it to Jerusalem and the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area, Ma'ale Adumim is one of the most prominent and well known settlements in the West Bank.

The international community considers Israeli settlements in the West Bank illegal under international law, but the Israeli government disputes this.[3]

Etymology

The town name "Ma'ale Adumim" is taken from the Joshua 15:7 and Joshua 18:17:[4] The boundary [of the tribe of Judah] ascended from the Valley of Achor to Debir and turned north to Gilgal, facing the Ascent of Adumim, which is south of the wadi. Literally "Ascent of Red", it takes its name from the red rock lining the ascent from the Dead Sea.[5]

History

Ma'ale Adumim was originally a Nahal outpost.[2] It was designed as a planned community and suburban commuter town for nearby Jerusalem, to which many residents commute daily.[6] In the early 1970s, Israel's Labor government discussed a plan to expand the boundaries of Jerusalem eastward by founding an industrial zone and a workers' village on the Jericho road.[7] In the winter of 1975, on the seventh night of Hanukkah, a Gush Emunim group of 23 families and six singles erected a prefabricated concrete structure and two wooden huts at the site now known as "Founder's Circle" in Mishor Adumim. The group was evicted several times. In 1977, after Menachem Begin took office, Ma'ale Adumim was granted official status as a permanent settlement.[7] In the late 1990s, approximately 1,050 Palestinian Jahalin Bedouins were forced to move from land that now forms part of the settlement.[8] Court orders required compensation by the Israeli government and they received cash, electricity and water supplies.[8] According to the residents, they had to sell most of their livestock and their Bedouin way of life ended.[8]

The chief urban planner was architect Rachel Walden. In March 1979, Maaleh Adumim achieved local council status.[9] The urban plan for Ma'ale Adumim, finalized in 1983, encompasses a total of 35 square kilometres (14 sq mi), of which 3.7 square kilometres (1.43 sq mi) have been built so far, in a bloc that includes Ma'ale Adumim, Mishor Adumim, Kfar Adumim, and Allon.[10]

The mayor of Ma'ale Adumim is Benny Kashriel, who was recently elected to a third term by a large majority.

Geography

The city is surrounded on four sides by the Judean Desert[2] and is linked to Jerusalem and the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area via Highway 1. Due to its strategic location between the northern and southern parts of the West Bank, Palestinians see this as a threat to the territorial continuity of a future Palestinian state. This claim is disputed by mayor Benny Kashriel, who claims that continuity would be attained by circling Ma'ale Adumim to the east.[11] Israeli drivers use a bypass road that exits the city to the west, entering Jerusalem through the French Hill Junction or a tunnel that goes under Mt. Scopus. These routes were built in the wake of the First and Second Intifadas when Palestinian militants shot at motorists and cars were stoned. The previous road passed through al-Eizariya and Abu Dis.

Land ownership

Peace Now initially claimed that 86.4% of Ma'ale Adumim was privately owned Palestinian land, basing the figure on data leaked from a government report.[12][13] After Peace Now petitioned the Israeli courts to have the official data released, the group revised the figure to 0.5 percent of the settlement is built on private land. Israel maintains that Maale Adumin was built on "state lands," or areas not registered in anyone's name, and that no private property was being seized for building.[13] Palestinians claim lands from the villages of Abu Dis, al-Eizariya, Al-Issawiya, At-Tur and 'Anata were expropriated for building in Ma'aleh Adumim.[14]

According to B'Tselem, an Israeli human rights organization, "The expropriation procedure used in Ma'ale Adummim is unprecedented in the settlement enterprise. Expropriation of land for settlement purposes is forbidden, not only under international law but also according to the long-standing, official position of Israeli governments. Most settlements were built on area that was declared state land or on land that was requisitioned - ostensibly temporarily - for military purposes. It appears that in Ma'ale Adummim, the government decided to permanently expropriate the land because it viewed the area as an integral part of Jerusalem that would forever remain under Israeli control."[15]

Economy

Many residents of Maaleh Adumim are employed in Jerusalem. Others work in Mishor Adumim, Ma'ale Adumim's industrial park, which is located on the road to the Dead Sea, about ten minutes from Jerusalem. The industrial zone houses 220 businesses,[2] among them textile plants, garages, food manufacturers, aluminum and metalworking factories, and printing companies.[16]

Demographics

In 2004, over seventy percent of the residents were secular. According to the municipal spokesman, the overwhelming majority moved to the city not for ideological reasons but for lower-cost housing and higher living standards. In 2004, 48 percent of residents were under the age of 18. Ma'aleh Adumim's unemployment rate was 2.1 percent, far below the national average.[7]

Education and culture

In 2011, Ma'ale Adumim had 21 schools and 80 kindergartens.[2] A large portion of Ma'ale Adumim's budget is spent on education. Schools offer after-school programs, class trips, and tutoring where needed. A special program has been developed for new immigrant children. Additional resources are invested in special education and classes for gifted children, including a special after-school program for honors students in science and math.[16] Ma'ale Adumim College was situated in the city, but is currently defunct. Religious elementary schools in Ma'ale Adumim include Ma'aleh Hatorah, Sde Chemed, and Tzemach Hasadeh. Religious high schools are Yeshiva Tichonit, Tzvia and Amit. The city has over 40 synagogues and several yeshivas, among them Yeshivat Birkat Moshe.[17] Ma'aleh Adumim has won the Israel Ministry of Education prize for excellence twice. It has also won the national prize for environmental quality in recognition of its emphasis on urban planning, green space, playgrounds and outdoor sculptures.[7]

Healthcare

Medical services are provided in the city through all four Health maintenance organizations (kupot holim). There is also a large geriatric hospital, Hod Adumim, also providing care for recuperating patients and chronic patients. It is also used for senior citizens residence. It has facilities for nursing, the elderly, the handicapped, through the most extreme needs.

Legal issues

In 2005, a report by John Dugard for the United Nations Commission on Human Rights stated that the "three major settlement blocs—Gush Etzion, Ma'ale Adumim and Ariel—will effectively divide Palestinian territory into cantons or Bantustans."[19] Israel says the solution is a bypass road similar to those used daily by Israelis to avoid driving through hostile Arab areas. The 2007 development project in east Ma'ale Adumim was supported by Ariel Sharon in 2005.[20] Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesman Mark Regev denied the 2007 extension plan is a violation of the roadmap peace plan, under which Israel agreed to freeze all building in the settlements.

In 2008, a project to link Ma'ale Adumim and Jerusalem, known as the E1 project—short for "East 1", as it appears on old zoning maps—was criticized by the Palestinian Authority, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and US President George W. Bush.[21] As a result, a plan for 3,500-5,000 homes in Mevaseret Adumim was frozen.[22] The new Judea and Samaria District police headquarters, formerly located in the Ras el-Amud neighborhood of Jerusalem, was completed in May 2008.[23]

Ma'ale Adumim is widely regarded by the international community as illegal under international law according to the Fourth Geneva Convention (article 49), which prohibits an occupying power transferring citizens from its own territory to occupied territory. Israel maintains that international conventions relating to occupied land do not apply to the West Bank because they were not under the legitimate sovereignty of any state in the first place.[24] This view was rejected by the International Court of Justice and the International Committee of the Red Cross.[25]

Housing shortage

One of the purposes of establishing Ma'aleh Adumim was to supply affordable housing for young couples who could not afford the high cost of homes in Jerusalem. Although the municipal boundaries cover 48,000 dunams, the city has been suffering from an acute housing shortage since 2009 due to the freeze on new construction. As of 2011 most of the real estate market was in second-hand properties.[2]

Archaeology

The Byzantine monastery of Martyrius, once the most important monastic centre in the Judean Desert in the early Christian era, is located in Ma'ale Adumim.[26] Other archeological sites on the outskirts of Ma'ale Adumim include the Khan el-Hatruri,[27] also known as the Inn of the Good Samaritan (cited in a parable by Jesus, in Luke 10:30–37),[28] and the remains of the Monastery of St. Euthymius built in the 5th century and destroyed by the Mamluk sultan Baybars.[29] Khan al-Ahmar is a 13th-century travelers inn for pilgrims on the route between Jerusalem and Mecca via Nabi Musa.[30]

Landmarks

The Moshe Castel Museum showcases the work of Israeli artist Moshe Castel.[31] Mizpe Edna is a lookout at the Shofar and Hallil junction.

Twin towns – Sister cities

References

- ↑ "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Unsettled Market, Jerusalem Post, In Jerusalem, May 13, 2011

- ↑ "The Geneva Convention". BBC News. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ Bitan, Hanna: 1948–1998: Fifty Years of 'Hityashvut': Atlas of Names of Settlements in Israel, Jerusalem 1999, Carta, p. 41, ISBN 965-220-423-4 (Hebrew)

- ↑ "Ma'aleh Adumim - History". Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ The Olive Trees of Ma'ale Adumim

- 1 2 3 4 Growing to Jerusalem, The Jerusalem Report

- 1 2 3 Abdalla, Jihan. "Israel eyes landfill site for Bedouin nomads". Reuters. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ "Municipality of Ma'ale Adumim". Toshav.co.il. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ a b "The Expansion of Ma'ale Adumim". Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem (ARIJ). Archived from the original on 2006-01-08. Retrieved 2006-02-10.

- ↑ Berg, Raffi (2005-11-12). "Israel's 'Linchpin' Settlement". BBC. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/6168752.stm "According to the report, 86.4% of the Maale Adumim settlement block, the largest in the West Bank, is built on private Palestinian land"

- 1 2 Shragai, Nadav (2007-03-14). "Peace Now: 32% of land held for settlements is private Palestinian property". Haaretz. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ↑ http://mondediplo.com/1999/11/08israel "Maaleh Adumim was established on lands taken from Palestinians, from the villages of Abu Dis, Al Izriyyeh, Al Issawiyyeh, Al Tur and Anata. Other lands had been inhabited for dozen of years by the Jahalin and Sawahareh Bedouin tribes."

- ↑ "The Hidden Agenda: The Establishment and Expansion Plans of Ma'ale Adummim and their Human Rights Ramifications | B'Tselem". Btselem.org. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- 1 2 "Maaleh Adumim real-estate". Buyit in Israel. 2010.

- ↑ Kehillot Tehilla: Finding the Right Community Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem

- ↑ Dugard, John (2005-03-03). "Question of the Violation of Human Rights in the Occupied Arab Territories, Including Palestine" (PDF). Report to the Commission on Human Rights. United Nations. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ "Sharon Pledges Settlement Growth". BBC. 2005-04-05. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ Benhorin, Yitzhak (2005-03-25). "Rice Slams Israel's Settlements Plans". Ynetnews. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ Lis, Jonathan (January 7, 2008). "Police delay move into new E-1 headquarters, but deny link to presidential visit". Haaretz.

- ↑ Middle East Progess

- ↑ Berg, Raffi (2005-11-12). "Israel's 'linchpin' settlement". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory International Court of Justice, 9 July 2004. pp. 44–45

- ↑ "The Monastery of Martyrius at Ma'ale Adummim", Yitzhak Magen, Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem 1993

- ↑ Rossner, Rena (2004-06-14). "Jerusalem Report Article". Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ "Tours from Jerusalem". Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ "Historical Sites". Jericho Municipality. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford University Press US. p. 335. ISBN 0-19-923666-6.

- ↑ "Moshe Castel Museum".

- ↑ Alexander, Amanda (December 16, 2010). "Maale Adumim becomes Williamsport's sister city".

External links

- Official municipal website

- Unofficial city website

- Americans for Peace Now report on E-1 and Ma'ale Adumim

- The Establishment and Expansion Plans of Ma'ale Adummim and their Human Rights Ramifications

- History of Ma'aleh Adummim

- UrbanIsrael Site: About Ma'ale Adumim: Historical, Social and Cultural Links

- Peace Now's Blunder: Erred on Ma'ale Adumim Land by 15,900 Percent

- Nefesh B'Nefesh Community Guide for Ma'ale Adumim, Israel

- Tehilla Community Guide for Ma'ale Adumim, Israel

- Places To Visit In Israel - Ma'ale Adumim

- There is water under the desert

- MAchat - Ma'ale Adumim English Speakers Community Website

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ma'ale Adumim. |