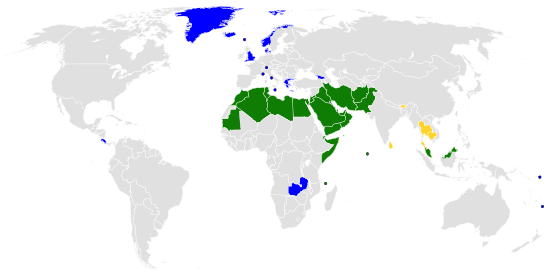

State religion

.svg.png)

A state religion (also called an established religion, state church, established church, or official religion) is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state. A state with an official religion, while not secular, is not necessarily a theocracy – a country whose rulers have in their hands both secular and spiritual authority.

Official religions have been known throughout human history in almost all types of cultures. They were adopted by most ancient states, both monoethnic and polyethnic, and observing them was a requirement made to all citizens, and especially public officials.

Official religions justified and reinforced the type of government existing in a society. Sanctifying it as the most, or the only, correct (divine) one, they often put forward and/or supported ideas of its expansion to other lands, whether the latter already follow the same religion or, sometimes not.

As the term church is typically applied to a Christian place of worship and organizations incorporating such ones, the term state church is associated with Christianity, historically the state church of the Roman Empire in the last centuries of the Empire's existence, and is sometimes used to denote a specific modern national branch of Christianity. Closely related to state churches are what sociologists call ecclesiae, though the two are slightly different.

State religions are official or government-sanctioned establishments of a religion, but neither does the state need be under the control of the religion (as in a theocracy), nor is the state-sanctioned religion necessarily under the control of the state.

The institution of state-sponsored religious cults is ancient, reaching into the Ancient Near East and prehistory. The relation of religious cult and the state was discussed by Varro, under the term of theologia civilis ("civic theology"). The first state-sponsored Christian church was the Armenian Apostolic Church, established in 301 AD.[1]

In the Near East and Middle East, many states with mostly Islamic population have Islam as their state religion in its Shiite and Sunni variety, though the degree of religious restrictions on the citizen's everyday life varies. On the one hand, rulers of Saudi Arabia join secular and religious power in their hands, and Iran's secular presidents since the revolution of 1979 are supposed to follow decisions of religious authorities. Turkey, which also has mostly Muslim population, after its 1920s revolution became a secular country, though unlike Russian revolution of the same decade, it did not make the country atheistic.

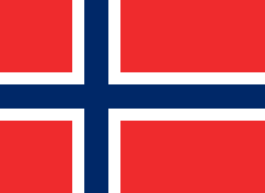

The degree that an official religion is imposed upon citizens in contemporary society varies considerably from total as in Saudi Arabia to not at all as in Norway.

Types of state religion

The degree and nature of state backing for denomination or creed designated as a state religion can vary. It can range from mere endorsement (with or without financial support) with freedom for other faiths to practice, to prohibiting any competing religious body from operating and to persecuting the followers of other sects. In Europe, competition between Catholic and Protestant denominations for state sponsorship in the 16th century evolved the principle cuius regio eius religio ("states follow the religion of the ruler") embodied in the text of the treaty that marked the Peace of Augsburg, 1555. In England, Henry VIII broke with Rome in 1534, being declared the "Supreme Head on earth of the Church of England",[2] the official religion of England continued to be "Catholicism without the Pope" until after his death in 1547,[3] while in Scotland the Church of Scotland opposed the religion of the ruler.

In some cases, an administrative region may sponsor and fund a set of religious denominations; such is the case in Alsace-Moselle in France under its local law, following the pre-1905 French concordatry legal system and patterns in Germany.[4]

In some communist states, notably in North Korea and Cuba, the state sponsors religious organizations, and activities outside those state-sponsored religious organizations are met with various degrees of official disapproval. In these cases, state religions are widely seen as efforts by the state to prevent alternate sources of authority.

State churches

There is also a difference between a "state church" and the broader term of "state religion". A "state church" is a state religion created by a state for use exclusively by that state. An example of a "state religion" that's not also a "state church" is Roman Catholicism in Costa Rica, which was accepted as the state religion in the 1949 Constitution, despite the lack of a national church. In the case of a "state church", the state has absolute control over the church, but in the case of a "state religion", the church is ruled by an exterior body; in the case of Catholicism, the Vatican has control over the church. In either case, the official state religion has some influence over the ruling of the state. As of 2012, there are only seven state churches left, as most countries that once featured state churches have separated the church from their government.

Disestablishment

Disestablishment is the process of repealing a church's status as an organ of the state. Opponents of disestablishment of the Church of England were known as antidisestablishmentarians.

Current state religions

Currently, the following religions have been established as state religions in some countries. All are versions of Christianity, Islam or Buddhism.

Christian countries

The following states recognize some form of Christianity as their state or official religion (by denomination):

Roman Catholicism

Jurisdictions where Roman Catholicism has been established as a state or official religion:

-

Costa Rica: article 75 of the constitution of Costa Rica confirms that "The Roman Catholic and Apostolic Religion is the religion of the State, which contributes to its maintenance, without preventing the free exercise in the Republic of other forms of worship that are not opposed to universal morality or good customs."[5]

Costa Rica: article 75 of the constitution of Costa Rica confirms that "The Roman Catholic and Apostolic Religion is the religion of the State, which contributes to its maintenance, without preventing the free exercise in the Republic of other forms of worship that are not opposed to universal morality or good customs."[5] -

Liechtenstein: the constitution of Liechtenstein describes the Catholic Church as the state religion and enjoying "the full protection of the State". The constitution does however ensure that people of other faiths "shall be entitled to practise their creeds and to hold religious services to the extent consistent with morality and public order."[6]

Liechtenstein: the constitution of Liechtenstein describes the Catholic Church as the state religion and enjoying "the full protection of the State". The constitution does however ensure that people of other faiths "shall be entitled to practise their creeds and to hold religious services to the extent consistent with morality and public order."[6] -

Malta: Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta declares that "the religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion"[7]

Malta: Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta declares that "the religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion"[7] -

Monaco: article 9 of the constitution of Monaco describes "La religion catholique, apostolique et romaine" [the catholic, apostolic and Roman religion]" as the religion of the state.[8]

Monaco: article 9 of the constitution of Monaco describes "La religion catholique, apostolique et romaine" [the catholic, apostolic and Roman religion]" as the religion of the state.[8] -

Vatican City: the Vatican is an Elective, Theocratic, or sacerdotal Absolute Monarchy[9] ruled by the Pope, who is also the Vicar of the Catholic Church. The highest state functionaries are all Catholic clergy of various national origins. It is the sovereign territory of the Holy See (Latin: Sancta Sedes) and the location of the Pope's official residence, referred to as the Apostolic Palace.

Vatican City: the Vatican is an Elective, Theocratic, or sacerdotal Absolute Monarchy[9] ruled by the Pope, who is also the Vicar of the Catholic Church. The highest state functionaries are all Catholic clergy of various national origins. It is the sovereign territory of the Holy See (Latin: Sancta Sedes) and the location of the Pope's official residence, referred to as the Apostolic Palace.

Jurisdictions that give various degrees of recognition in their constitutions to Roman Catholicism without establishing it as the state religion:

-

Andorra

Andorra -

Argentina – article 2 of the Constitution explicitly states that the government supports the Catholic Church, but the constitution does not establish a state religion.[10][11]

Argentina – article 2 of the Constitution explicitly states that the government supports the Catholic Church, but the constitution does not establish a state religion.[10][11] -

Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic -

El Salvador

El Salvador -

Panama – the Constitution recognizes Catholicism as "the religion of the majority" of citizens but does not designate it as the official state religion.[12]

Panama – the Constitution recognizes Catholicism as "the religion of the majority" of citizens but does not designate it as the official state religion.[12] -

Paraguay[13]

Paraguay[13] -

Peru[14]

Peru[14] -

Poland[15]

Poland[15]

Eastern Orthodoxy

The jurisdictions below give various degrees of recognition in their constitutions to Eastern Orthodoxy, but without establishing it as the state religion:

-

Greece: The Church of Greece is recognized by the Greek Constitution as the prevailing religion in Greece.[16] However, this provision does not give official status to the Church of Greece, while all other religions are recognized as equal and may be practiced freely.[17] Therefore, this provision is considered a dead letter and can only be interpreted as a nationalistic historical remnant.

Greece: The Church of Greece is recognized by the Greek Constitution as the prevailing religion in Greece.[16] However, this provision does not give official status to the Church of Greece, while all other religions are recognized as equal and may be practiced freely.[17] Therefore, this provision is considered a dead letter and can only be interpreted as a nationalistic historical remnant. -

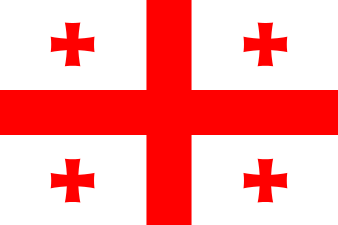

Georgia: Georgian Orthodox Church is not the state church of Georgia but has a special constitutional agreement with the state, with the constitution recognising "the special role of the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia in the history of Georgia and its independence from the state."[18] (See also Concordat of 2002)

Georgia: Georgian Orthodox Church is not the state church of Georgia but has a special constitutional agreement with the state, with the constitution recognising "the special role of the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia in the history of Georgia and its independence from the state."[18] (See also Concordat of 2002) -

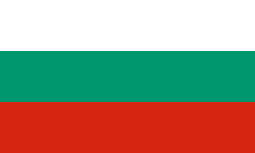

Bulgaria: in the Bulgarian Constitution, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church is recognized as "the traditional religion" of the Bulgarian people, but the state itself remains secular.

Bulgaria: in the Bulgarian Constitution, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church is recognized as "the traditional religion" of the Bulgarian people, but the state itself remains secular.

Protestantism

Anglicanism

-

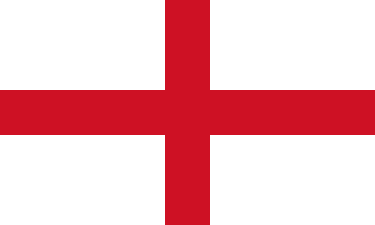

England: the Church of England is the established church in England, but not in the United Kingdom as a whole.[19] It is the only established Anglican church worldwide. The Anglican Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church and the Church of Ireland are not established churches and they are independent from the Church of England. The British monarch is the titular Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The 26 most senior bishops in the Church of England are Lords Spiritual and have seats in the House of Lords of the UK Parliament. Scottish, Welsh and Irish Anglican bishops do not sit in the House of Lords.

England: the Church of England is the established church in England, but not in the United Kingdom as a whole.[19] It is the only established Anglican church worldwide. The Anglican Church in Wales, the Scottish Episcopal Church and the Church of Ireland are not established churches and they are independent from the Church of England. The British monarch is the titular Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The 26 most senior bishops in the Church of England are Lords Spiritual and have seats in the House of Lords of the UK Parliament. Scottish, Welsh and Irish Anglican bishops do not sit in the House of Lords.

In the 19th century, there was a campaign by Liberals, dissenters and nonconformists to disestablish the Church of England. The campaign for disestablishment was revived in the 20th century when Parliament rejected the 1928 revision of the Book of Common Prayer, leading to calls for separation of church and state to prevent political interference in matters of worship. Nevertheless, the Church of England remained the state church.

Calvinism

-

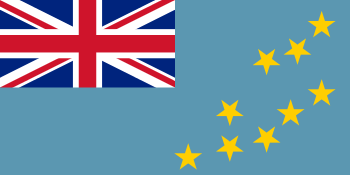

Tuvalu: The Church of Tuvalu is the state religion, although in practice this merely entitles it to "the privilege of performing special services on major national events".[20] The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees freedom of religion, including the freedom to practice, the freedom to change religion, the right not to receive religious instruction at school or to attend religious ceremonies at school, and the right not to "take an oath or make an affirmation that is contrary to his religion or belief".[21]

Tuvalu: The Church of Tuvalu is the state religion, although in practice this merely entitles it to "the privilege of performing special services on major national events".[20] The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees freedom of religion, including the freedom to practice, the freedom to change religion, the right not to receive religious instruction at school or to attend religious ceremonies at school, and the right not to "take an oath or make an affirmation that is contrary to his religion or belief".[21] -

Scotland: The Church of Scotland is recognized as the national church of Scotland, but is not a state church and thus differs from the Church of England. Its constitution, which is recognised by acts of the British Parliament, gives it complete independence from the state.

Scotland: The Church of Scotland is recognized as the national church of Scotland, but is not a state church and thus differs from the Church of England. Its constitution, which is recognised by acts of the British Parliament, gives it complete independence from the state.

Lutheranism

Jurisdictions where a Lutheran church has been established as a state religion include the Nordic countries.

-

Denmark: section 4 of the Danish constitution confirms the Church of Denmark as the state church.[22]

Denmark: section 4 of the Danish constitution confirms the Church of Denmark as the state church.[22]

-

Faroe Islands: the Church of the Faroe Islands is the state church of the Faroe Islands, an autonomous country within the Danish Realm.

Faroe Islands: the Church of the Faroe Islands is the state church of the Faroe Islands, an autonomous country within the Danish Realm. -

Greenland: the Church of Denmark is the state church of Greenland, an autonomous country within the Danish Realm.

Greenland: the Church of Denmark is the state church of Greenland, an autonomous country within the Danish Realm.

-

-

Iceland: the Icelandic constitution confirms the Church of Iceland as the state church of Iceland.[23]

Iceland: the Icelandic constitution confirms the Church of Iceland as the state church of Iceland.[23] -

Norway: the Constitution of Norway stipulates that "The Church of Norway, an Evangelical-Lutheran church, will remain the Established Church of Norway and will as such be supported by the State."[24] This was amended in 2012, from "Evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State". The church is granted autonomy in doctrine and appointment of bishops.[25][26][27] A bill passed in 2016 creates the Church of Norway as an independent legal entity from 1 January 2017.[28][29]

Norway: the Constitution of Norway stipulates that "The Church of Norway, an Evangelical-Lutheran church, will remain the Established Church of Norway and will as such be supported by the State."[24] This was amended in 2012, from "Evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State". The church is granted autonomy in doctrine and appointment of bishops.[25][26][27] A bill passed in 2016 creates the Church of Norway as an independent legal entity from 1 January 2017.[28][29] -

Finland: the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland has a special relationship with the Finnish state, its internal structure being described in a special law, the Church Act.[30] The Church Act can be amended only by a decision of the synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and subsequent ratification by the Parliament of Finland. The Church Act is protected by the Finnish Constitution and the state can not change the Church Act without changing the constitution. The church has a power to tax its members and all corporations unless a majority of shareholders are members of the Finnish Orthodox Church. The state collects these taxes for the church, for a fee. On the other hand, the church is required to give a burial place for everyone in its graveyards.[31] The President of the Republic of Finland also decides the themes for intercession days. The church does not consider itself a state church, as the Finnish state does not have the power to influence its internal workings or its theology, although it has a veto in those changes of the internal structure which require changing the Church Act. Neither does the Finnish state accord any precedence to Lutherans or the Lutheran faith in its own acts. The Union of Freethinkers of Finland has criticized the official endorsement of the two churches by the Finnish state, and has campaigned for the separation of church and state.[32]

Finland: the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland has a special relationship with the Finnish state, its internal structure being described in a special law, the Church Act.[30] The Church Act can be amended only by a decision of the synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and subsequent ratification by the Parliament of Finland. The Church Act is protected by the Finnish Constitution and the state can not change the Church Act without changing the constitution. The church has a power to tax its members and all corporations unless a majority of shareholders are members of the Finnish Orthodox Church. The state collects these taxes for the church, for a fee. On the other hand, the church is required to give a burial place for everyone in its graveyards.[31] The President of the Republic of Finland also decides the themes for intercession days. The church does not consider itself a state church, as the Finnish state does not have the power to influence its internal workings or its theology, although it has a veto in those changes of the internal structure which require changing the Church Act. Neither does the Finnish state accord any precedence to Lutherans or the Lutheran faith in its own acts. The Union of Freethinkers of Finland has criticized the official endorsement of the two churches by the Finnish state, and has campaigned for the separation of church and state.[32] -

Sweden: the Church of Sweden was until 2000 the official state church of Sweden, and Lutheranism was therefore the state religion of Sweden. In spite of the separation between the state and the church in 2000, the Church of Sweden still has a special status in Sweden. Sweden is therefore often seen as a midway between having a state religion and not. The church has its own legal regulation in the 1998 Church of Sweden Act, which regulates the church's basic structure, creeds and right to tax members of the church. According to the Act, the Church of Sweden must be a democratic, Lutheran people's church. Only the Swedish Riksdag can change this fact. The connections to the Swedish royal family are complicated. For example, the Swedish constitution stipulates that the Monarch of Sweden must be a true Lutheran, accepting the doctrine of the Church of Sweden. All members of the royal house must accept the same doctrine to be able to inherit the Throne of Sweden. The parishes of the Church of Sweden were the smallest administrative entities in Sweden and were used as civil registration and taxation units until 1 January 2016.[33]

Sweden: the Church of Sweden was until 2000 the official state church of Sweden, and Lutheranism was therefore the state religion of Sweden. In spite of the separation between the state and the church in 2000, the Church of Sweden still has a special status in Sweden. Sweden is therefore often seen as a midway between having a state religion and not. The church has its own legal regulation in the 1998 Church of Sweden Act, which regulates the church's basic structure, creeds and right to tax members of the church. According to the Act, the Church of Sweden must be a democratic, Lutheran people's church. Only the Swedish Riksdag can change this fact. The connections to the Swedish royal family are complicated. For example, the Swedish constitution stipulates that the Monarch of Sweden must be a true Lutheran, accepting the doctrine of the Church of Sweden. All members of the royal house must accept the same doctrine to be able to inherit the Throne of Sweden. The parishes of the Church of Sweden were the smallest administrative entities in Sweden and were used as civil registration and taxation units until 1 January 2016.[33]

Methodism

In 1928, Queen Salote Tupou III, who was a member of the church, established the Free Wesleyan Church as the state religion of Tonga. The chief pastor of the Free Wesleyan Church serves as the representative of the people of Tonga and of the Church at the coronation of a King or Queen of Tonga where he anoints and crowns the Monarch. In Opposition to the establishment of the Free Wesleyan Church as a state religion, the Church of Tonga separated from the Free Wesleyan Church in 1928.

Other/Mixed

-

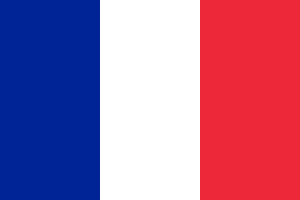

France: The local law in Alsace-Moselle accords official status to four religions in this specific region of France: Judaism, Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism. The law is a remnant of the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801, which was abrogated in the rest of France by the law of 1905 on the separation of church and state. However, at the time, Alsace-Moselle had been annexed by Germany. The Concordat therefore remained in force in these areas, and it was not abrogated when France regained control of the region in 1918. The Concordat recognises four religious traditions in Alsace-Moselle: the Jewish religion and three branches of Christianity: Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed. Therefore, the separation of church and state, part of the French concept of Laïcité, does not apply in this region.[34]

France: The local law in Alsace-Moselle accords official status to four religions in this specific region of France: Judaism, Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism. The law is a remnant of the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801, which was abrogated in the rest of France by the law of 1905 on the separation of church and state. However, at the time, Alsace-Moselle had been annexed by Germany. The Concordat therefore remained in force in these areas, and it was not abrogated when France regained control of the region in 1918. The Concordat recognises four religious traditions in Alsace-Moselle: the Jewish religion and three branches of Christianity: Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed. Therefore, the separation of church and state, part of the French concept of Laïcité, does not apply in this region.[34] -

Hungary: The preamble to the Hungarian Constitution of 2011 describes Hungary as "part of Christian Europe" and acknowledges "the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood", while Article VII provides that "the State shall cooperate with the Churches for community goals". However, the constitution also guarantees freedom of religion and separation of church and state.[35]

Hungary: The preamble to the Hungarian Constitution of 2011 describes Hungary as "part of Christian Europe" and acknowledges "the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood", while Article VII provides that "the State shall cooperate with the Churches for community goals". However, the constitution also guarantees freedom of religion and separation of church and state.[35] -

Zambia: The preamble to the Zambian Constitution of 1991 declares Zambia to be "a Christian nation", while also guaranteeing freedom of religion.[36]

Zambia: The preamble to the Zambian Constitution of 1991 declares Zambia to be "a Christian nation", while also guaranteeing freedom of religion.[36]

Muslim countries

Many Muslim-majority countries have constitutionally established Islam, or a specific form of it, as a state religion. Proselytism (converting people to another religion) is often illegal.

Islam (non-denominational)

States which define Islam as the state religion, but do not specify either Sunni or Shia.

-

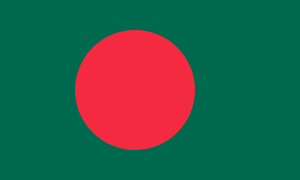

Bangladesh : The 1972 constitution did not include any religion as the state religion. However, in 1988, general Ershad inserted Islam as the state religion by the Eighth Amendment Act. 1988; section 2A specifies "The state religion of the Republic is Islam, but other religions may be practiced in peace and harmony in the Republic.".[37] As part of a series of rulings, on 4 October 2010 the High Court ruled that Bangladesh is a secular state.[38] Section 12 of part II of the constitution identifies Secularism and freedom of religion as fundamental principles of state policy[39]

Bangladesh : The 1972 constitution did not include any religion as the state religion. However, in 1988, general Ershad inserted Islam as the state religion by the Eighth Amendment Act. 1988; section 2A specifies "The state religion of the Republic is Islam, but other religions may be practiced in peace and harmony in the Republic.".[37] As part of a series of rulings, on 4 October 2010 the High Court ruled that Bangladesh is a secular state.[38] Section 12 of part II of the constitution identifies Secularism and freedom of religion as fundamental principles of state policy[39] -

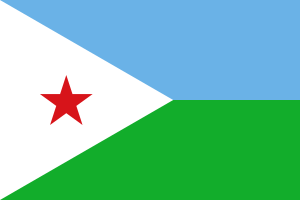

Djibouti[40]

Djibouti[40] -

Iraq : Article 2 of the Constitution of Iraq confirms Islam as the official religion of the State.

Iraq : Article 2 of the Constitution of Iraq confirms Islam as the official religion of the State. -

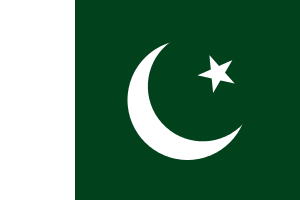

Pakistan : article 2 of the Constitution of Pakistan confirms Islam as the state religion.[41]

Pakistan : article 2 of the Constitution of Pakistan confirms Islam as the state religion.[41] -

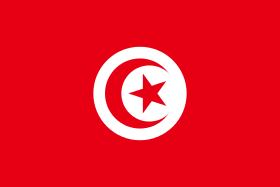

Tunisia: Art. 1, Constitution of Tunisia

Tunisia: Art. 1, Constitution of Tunisia

Sunni Islam

-

Afghanistan: Article 1 & 2, Constitution of Afghanistan

Afghanistan: Article 1 & 2, Constitution of Afghanistan -

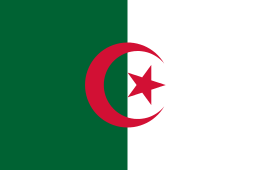

Algeria: Art. 2, Constitution of Algeria

Algeria: Art. 2, Constitution of Algeria -

Brunei: Art. 3, Constitution of Brunei

Brunei: Art. 3, Constitution of Brunei -

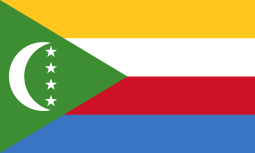

Comoros

Comoros -

Egypt: Article 2, Egyptian Constitution of 2014

Egypt: Article 2, Egyptian Constitution of 2014 -

Jordan: Article 2, Constitution of Jordan

Jordan: Article 2, Constitution of Jordan -

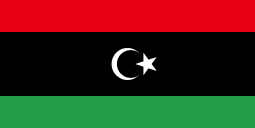

Libya

Libya -

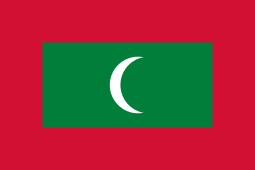

Maldives

Maldives -

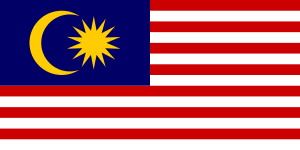

Malaysia: Article 3, Constitution of Malaysia

Malaysia: Article 3, Constitution of Malaysia -

Mauritania: Article 5, Constitution of Mauritania

Mauritania: Article 5, Constitution of Mauritania -

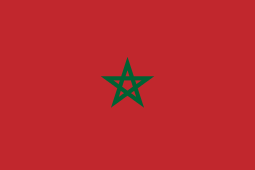

Morocco

Morocco -

Qatar: Article 1, Constitution of Qatar

Qatar: Article 1, Constitution of Qatar -

Saudi Arabia: Article 1, Basic Law of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia: Article 1, Basic Law of Saudi Arabia -

Somalia: Article 2, Constitution of Somalia

Somalia: Article 2, Constitution of Somalia -

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

Shiʾa Islam

-

Iran Theocratic-Republican hybrid. See Politics of Iran.

Iran Theocratic-Republican hybrid. See Politics of Iran.

Ibadi

Mixed Shia and Sunni

Buddhist countries

Governments where Buddhism, either a specific form of, or the whole, has been established as an official religion:

Theravada Buddhism

-

Cambodia[42]

Cambodia[42] -

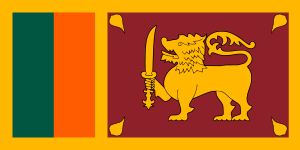

Sri Lanka: the constitution of Sri Lanka accords Buddhism the "foremost place", although it does not identify it as a state religion.[43]

Sri Lanka: the constitution of Sri Lanka accords Buddhism the "foremost place", although it does not identify it as a state religion.[43] -

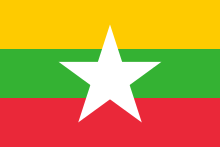

Myanmar: Section 361 of the constitution states that "The Union recognizes special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union.".[44]

Myanmar: Section 361 of the constitution states that "The Union recognizes special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union.".[44]

Vajrayana Buddhism

-

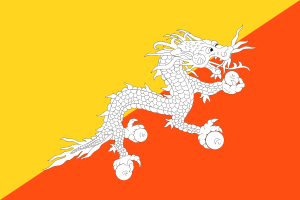

Bhutan: (Drukpa Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism)[45]

Bhutan: (Drukpa Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism)[45]

Status of religion in Israel

Israel is defined in several of its laws as a "Jewish and democratic state" (medina yehudit ve-demokratit). However, the term "Jewish" is a polyseme that can describe the Jewish people as either an ethnic or a religious group. The debate about the meaning of the term "Jewish" and its legal and social applications is one of the most profound issues with which Israeli society deals. The problem of the status of religion in Israel, even though it is relevant to all religions, usually refers to the status of Judaism in Israeli society. Thus, even though from a constitutional point of view Judaism is not the state religion in Israel, its status nevertheless determines relations between religion and state and the extent to which religion influences the political center.[46]

The State of Israel supports religious institutions, particularly Orthodox Jewish ones, and recognizes the "religious communities" as carried over from those recognized under the British Mandate - in turn derived from the pre-1917 Ottoman system of Millets. These are: Jewish and Christian (Eastern Orthodox, Latin [Catholic], Gregorian-Armenian, Armenian-Catholic, Syrian [Catholic], Chaldean [Uniate], Greek Catholic Melkite, Maronite, and Syrian Orthodox). The fact that the Muslim population was not defined as a religious community is a vestige of the Ottoman period during which Islam was the dominant religion and does not affect the rights of the Muslim community to practice their faith. At the end of the period covered by the 2009 U.S. International Religious Freedom Report, several of these denominations were pending official government recognition; however, the Government has allowed adherents of not officially recognized groups freedom to practice. In 1961, legislation gave Muslim Shari'a courts exclusive jurisdiction in matters of personal status. Three additional religious communities have subsequently been recognized by Israeli law: the Druze (prior under Islamic jurisdiction), the Evangelical Episcopal Church, and the Bahá'í.[47] These groups have their own religious courts as official state courts for personal status matters (see millet system).

The structure and goals of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel are governed by Israeli law, but the law does not say explicitly that it is a state Rabbinate. However, outspoken Israeli secularists such as Shulamit Aloni and Uri Avnery have long maintained that it is that in practice. Non-recognition of other streams of Judaism such as Reform Judaism and Conservative Judaism is the cause of some controversy; rabbis belonging to these currents are not recognized as such by state institutions and marriages performed by them are not recognized as valid. As pointed out by Avnery and Aloni, the essential problem is that Israel carries on the top-down Ottoman Millet system, under which the government reserves the complete discretion of recognizing some religions groups and not recognizing others. As of 2015 marriage in Israel provides no provision for civil marriage, marriage between people of different religions, marriages by people who do not belong to one of nine recognised religious communities, or same-sex marriages, although there is recognition of marriages performed abroad.

Political religions

In some countries, there is a political ideology sponsored by the government that may be called political religion.[48]

-

North Korea: the North Korean government has promulgated Juche as a political alternative to traditional religion. The doctrine advocates a strong nationalist propaganda basis and is fundamentally opposed to Christianity and Buddhism, the two largest religions on the Korean peninsula. Juche theoreticians have, however, incorporated religious ideas into the state ideology. According to government figures, Juche is the largest political religion in North Korea. The public practice of all other religions is overseen and subject to heavy surveillance by the state.

North Korea: the North Korean government has promulgated Juche as a political alternative to traditional religion. The doctrine advocates a strong nationalist propaganda basis and is fundamentally opposed to Christianity and Buddhism, the two largest religions on the Korean peninsula. Juche theoreticians have, however, incorporated religious ideas into the state ideology. According to government figures, Juche is the largest political religion in North Korea. The public practice of all other religions is overseen and subject to heavy surveillance by the state.

Additional notes

-

Indonesia does not declare or designate a state religion. However, the government does only recognize 6 religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism. The Constitution of Indonesia guarantees the freedom of religion and the practice of other religions and beliefs, including the animistic indigenous ones, is not prohibited by any laws. Indonesians practicing traditional polytheistic and animistic beliefs are often counted as "Hindu" for government purposes. Atheism or agnosticism, although not prosecuted, is discouraged by the state ideology of Pancasila. In addition, the province of Aceh receives a special status and a higher degree of autonomy, in which it may enact laws (qanuns) based on the Sharia and enforce it, especially to its Muslim residents.

Indonesia does not declare or designate a state religion. However, the government does only recognize 6 religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism. The Constitution of Indonesia guarantees the freedom of religion and the practice of other religions and beliefs, including the animistic indigenous ones, is not prohibited by any laws. Indonesians practicing traditional polytheistic and animistic beliefs are often counted as "Hindu" for government purposes. Atheism or agnosticism, although not prosecuted, is discouraged by the state ideology of Pancasila. In addition, the province of Aceh receives a special status and a higher degree of autonomy, in which it may enact laws (qanuns) based on the Sharia and enforce it, especially to its Muslim residents. -

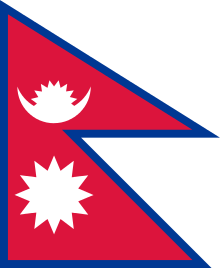

Nepal was once the world's only Hindu state, but has ceased to be so following a declaration by the Parliament in 2006.

Nepal was once the world's only Hindu state, but has ceased to be so following a declaration by the Parliament in 2006. - Many countries indirectly fund the activities of different religious denominations by granting tax-exempt status to churches and religious institutions which qualify as charitable organizations.[49][50] However, these religions are not established as state religions.

- In World Order of Bahá'u'lláh, first published in 1938, Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, described the anticipated world government of that religion as the "world’s future super-state" with the Bahá'í Faith as the "State Religion of an independent and Sovereign Power."[51]

Former state religions

Pre-modern era

Egypt and Sumer

The concept of state religions was known as long ago as the empires of Egypt and Sumer, when every city state or people had its own god or gods. Many of the early Sumerian rulers were priests of their patron city god. Some of the earliest semi-mythological kings may have passed into the pantheon, like Dumuzid, and some later kings came to be viewed as divine soon after their reigns, like Sargon the Great of Akkad. One of the first rulers to be proclaimed a god during his actual reign was Gudea of Lagash, followed by some later kings of Ur, such as Shulgi. Often, the state religion was integral to the power base of the reigning government, such as in Egypt, where Pharaohs were often thought of as embodiments of the god Horus.

Sassanid Empire

Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Sassanid dynasty which lasted until 651, when Persia was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate. However, it persisted as the state religion of the independent state of Hyrcania until the 15th century.

The tiny kingdom of Adiabene in northern Mesopotamia converted to Judaism around 34 CE.

Greek city-states

Many of the Greek city-states also had a god or goddess associated with that city. This would not be its only god/dess, but the one that received special honors. In ancient Greece, the city of Athens had Athena, Sparta had Ares, Delphi had Apollo and Artemis, Olympia had Zeus, Corinth had Poseidon and Thebes had Demeter.

Roman religion and Christianity

In Rome, the office of Pontifex Maximus came to be reserved for the Emperor, who was often declared a god posthumously, or sometimes during his reign. Failure to worship the Emperor as a god was at times punishable by death, as the Roman government sought to link emperor worship with loyalty to the Empire. Many Christians and Jews were subject to persecution, torture and death in the Roman Empire, because it was against their beliefs to worship the Emperor.

In 311, Emperor Galerius, on his deathbed, declared a religious indulgence to Christians throughout the Roman Empire, focusing on the ending of anti-Christian persecution. Constantine I and Licinius, the two Augusti, by the Edict of Milan of 313, enacted a law allowing religious freedom to everyone within the Roman Empire. Furthermore, the Edict of Milan cited that Christians may openly practice their religion unmolested and unrestricted, and provided that properties taken from Christians be returned to them unconditionally. Although the Edict of Milan allowed religious freedom throughout the Empire, it did not abolish nor disestablish the Roman state cult (Roman polytheistic paganism). The Edict of Milan was written in such a way as to implore the blessings of the deity.

Constantine called up the First Council of Nicaea in 325, although he was not a baptised Christian until years later. Despite enjoying considerable popular support, Christianity was still not the official state religion in Rome, although it was in some neighboring states such as Armenia, Iberia, and Aksum.

Roman Religion (Neoplatonic Hellenism) was restored for a time by Julian the Apostate from 361 to 363. Julian does not appear to have reinstated the persecutions of the earlier Roman emperors.

Catholic Christianity, as opposed to Arianism and other ideologies deemed heretical, was declared to be the state religion of the Roman Empire on 27 February 380[52] by the decree De Fide Catolica of Emperor Theodosius I.[53]

Han dynasty Confucianism

In China, the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) advocated Confucianism as the de facto state religion, establishing tests based on Confucian texts as an entrance requirement into government service—although, in fact, the "Confucianism" advocated by the Han emperors may be more properly termed a sort of Confucian Legalism or "State Confucianism". This sort of Confucianism continued to be regarded by the emperors, with a few notable exceptions, as a form of state religion from this time until the overthrow of the imperial system of government in 1911. Note however, there is a debate over whether Confucianism (including Neo-confucianism) is a religion or purely a philosophical system.[54]

Yuan dynasty Buddhism

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271 – 1368 AD), Tibetan Buddhism was established as the de facto state religion by the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty. The top-level department and government agency known as the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Xuanzheng Yuan) was set up in Khanbaliq (modern Beijing) to supervise Buddhist monks throughout the empire. Since Kublai Khan only esteemed the Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhism, other religions became less important. Before the end of the Yuan dynasty, 14 leader of the Sakya sect had held the post of Imperial Preceptor (Dishi), thereby enjoy special power.[55]

Golden Horde and Ilkhanate

Shamanism and Buddhism were once the dominant religions among the ruling class of the Mongol khanates of Golden Horde and Ilkhanate, the two western khanates of the Mongol Empire. In the early days, the rulers of both khanates increasingly adopted Tibetan Buddhism, similar to the Yuan dynasty at that time. However, the Mongol rulers Ghazan of Ilkhanate and Uzbeg of Golden Horde converted to Islam in 1295 AD because of the Muslim Mongol emir Nawruz and in 1313 AD because of Sufi Bukharan sayyid and sheikh Ibn Abdul Hamid respectively. Their official favoring of Islam as the state religion coincided with a marked attempt to bring the regime closer to the non-Mongol majority of the regions they ruled. In Ilkhanate, Christian and Jewish subjects lost their equal status with Muslims and again had to pay the poll tax; Buddhists had the starker choice of conversion or expulsion.[56] In Golden Horde, Buddhism and Shamanism among the Mongols were proscribed, and by 1315, Uzbeg had successfully Islamicized the Horde, killing Jochid princes and Buddhist lamas who opposed his religious policy and succession of the throne.

Modern era

Europe

-

Netherlands: Article 133 of the 1814 Constitution stipulated the Sovereign Prince should be a member of the Reformed Church; this provision was dropped in the 1815 Constitution.[57] The 1815 Constitution also provided for a state salary and pension for the priesthood of established religions at the time (Protestantism, Catholicism and Judaism). This settlement, nicknamed de zilveren koorde (the silver cord), was abolished in 1983.[58][59][60]

Netherlands: Article 133 of the 1814 Constitution stipulated the Sovereign Prince should be a member of the Reformed Church; this provision was dropped in the 1815 Constitution.[57] The 1815 Constitution also provided for a state salary and pension for the priesthood of established religions at the time (Protestantism, Catholicism and Judaism). This settlement, nicknamed de zilveren koorde (the silver cord), was abolished in 1983.[58][59][60]

Former state churches in British North America

Protestant colonies

- The colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, New Haven, and New Hampshire were founded by Puritan Calvinist Protestants.

- The colonies of New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia maintained the Church of England as the established church.

- The Colony of Maryland was founded by a charter granted in 1632 to George Calvert, secretary of state to Charles I, and his son Cecil, both recent converts to Roman Catholicism. Under their leadership many English Catholic gentry families settled in Maryland. However, the colonial government was officially neutral in religious affairs, granting toleration to all Christian groups and enjoining them to avoid actions which antagonized the others. On several occasions, low-church dissenters led insurrections which temporarily overthrew the Calvert rule. In 1689, when William and Mary came to the English throne, they acceded to demands to revoke the original royal charter. In 1701, the Church of England was proclaimed, and in the course of the 18th century Maryland Catholics were first barred from public office, then disenfranchised, although not all of the laws passed against them (notably laws restricting property rights and imposing penalties for sending children to be educated in foreign Catholic institutions) were enforced, and some Catholics even continued to hold public office.

Catholic colonies

- When New France was transferred to Great Britain in 1763, the Roman Catholic Church remained under toleration, but Huguenots were allowed entrance where they had formerly been banned from settlement by Parisian authorities.

- When Spanish Florida was ceded to Great Britain in 1763, the British divided Florida into two colonies, East and West Florida, which both continued a policy of toleration for the Catholic residents.

Colonies with no established church

- The Province of Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers, but the colony never had an established church.

- The Province of New Jersey, without official religion, had a significant Quaker lobby, but Calvinists of all types also had a presence.

- Delaware Colony had no established church, but was contested between Catholics and Quakers.

- The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, founded by religious dissenters forced to flee the Massachusetts Bay colony, is widely regarded as the first polity to grant religious freedom to all its citizens, although Catholics were barred intermittently. Baptists, Seekers/Quakers and Jews made this colony their home. The King Charles Charter of 1663 guaranteed "full liberty in religious concernments".

Tabular summary

| Colony | Denomination | Disestablished[note 1] |

|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | Congregational | 1818[62] |

| Georgia | Church of England | 1789[note 2] |

| Maryland | Church of England | 1776 |

| Massachusetts | Congregational | 1834 (parish church system)[note 3] |

| New Brunswick | Church of England | |

| New Hampshire | Congregational | 1790[note 4] |

| Newfoundland | Church of England | |

| North Carolina | Church of England | 1776[note 5] |

| Nova Scotia | Church of England | 1850 |

| Prince Edward Island | Church of England | |

| South Carolina | Church of England | 1790 |

| Canada West | Church of England | 1854 |

| West Florida | Church of England[note 6] | 1783[note 7] |

| East Florida | Church of England[note 6] | 1783[note 7] |

| Virginia | Church of England | 1786[note 8] |

| West Indies | Church of England | 1868 (Barbados, not until 1969) |

- ↑ In several colonies, the establishment ceased to exist in practice at the Revolution, about 1776;[61] this is the date of permanent legal abolition.

- ↑ In 1789 the Georgia Constitution was amended as follows: "Article IV. Section 10. No person within this state shall, upon any pretense, be deprived of the inestimable privilege of worshipping God in any manner agreeable to his own conscience, nor be compelled to attend any place of worship contrary to his own faith and judgment; nor shall he ever be obliged to pay tithes, taxes, or any other rate, for the building or repairing any place of worship, or for the maintenance of any minister or ministry, contrary to what he believes to be right, or hath voluntarily engaged. To do. No one religious society shall ever be established in this state, in preference to another; nor shall any person be denied the enjoyment of any civil right merely on account of his religious principles."

- ↑ From 1780 to 1824, Massachusetts residents were all required to attend a parish church, the denomination of which was chosen by majority vote of town residents, but in effect this de facto established Congregationalism as the state religion. For details see Constitution of Massachusetts.

- ↑ Until 1877 the New Hampshire Constitution required members of the State legislature to be of the Protestant religion. Until 1968 the Constitution allowed for state funding of Protestant classrooms but not Catholic classrooms.

- ↑ The North Carolina Constitution of 1776 disestablished the Anglican church, but until 1835 the NC Constitution allowed only Protestants to hold public office. From 1835–1876 it allowed only Christians (including Catholics) to hold public office. Article VI, Section 8 of the current NC Constitution forbids "any person who shall deny the being of Almighty God" from holding public office. Such clauses were held by the United States Supreme Court to be unenforceable in the 1961 case of Torcaso v. Watkins, when the court ruled unanimously that the First and Fourteenth Amendment protections prohibiting federal religious tests also applied to the states under the doctrine of incorporation.

- 1 2 Religious tolerance for Catholics with an established Church of England was policy in the former Spanish Colonies of East and West Florida while under British rule.

- 1 2 In 1783 Peace of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War, the British ceded both East and West Florida back to Spain (see Spanish Florida).

- ↑ Tithes for the support of the Anglican Church in Virginia were suspended in 1776, and never restored. 1786 is the date of the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, which prohibited any coercion to support any religious body.

Non-British colonies

These areas were disestablished and dissolved, yet their presences were tolerated by the English and later British colonial governments, as Foreign Protestants, whose communities were expected to observe their own ways without causing controversy or conflict for the prevalent colonists. After the Revolution, their ethno-religious backgrounds were chiefly sought as the most compatible non-British Isles immigrants.

- New Netherland was founded by Dutch Reformed Calvinists.

- New Sweden was founded by Church of Sweden Lutherans.

State of Deseret

The State of Deseret was a provisional state of the United States, proposed in 1849, by Mormon settlers in Salt Lake City. The provisional state existed for slightly over two years, but attempts to gain recognition by the United States government foundered for various reasons. The Utah Territory which was then founded was under Mormon control, and repeated attempts to gain statehood met resistance, in part due to concerns over the principle of separation of church and state conflicting with the practice of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints of placing their highest value on "following counsel" in virtually all matters relating to their church-centered lives. The state of Utah was eventually admitted to the union on 4 January 1896, after the various issues had been resolved.[63]

States without a state religion

A state that does not profess a state religion is known as a secular state.

Established churches and former state churches

- ↑ Brazilian Laws - the Federal Constitution - The Organization of State. V-brazil.com. Retrieved 5 May 2012. Brazil had Roman Catholicism as the state religion from the country's independence, in 1822, until the fall of the Brazilian Empire. The new Republican government passed, in 1890, Decree 119-A "Decreto 119-A".

Prohibits federal and state authorities to intervene on religion, granting freedom of religion.

(still in force), instituting the separation of church and state for the first time in Brazilian law. Positivist thinker Demétrio Nunes Ribeiro urged the new government to adopt this stance. The 1891 Constitution, the first under the Republican system of government, abolished privileges for any specific religion, reaffirming the separation of church and state. This has been the case ever since – the 1988 Constitution of Brazil, currently in force, does so in its Nineteenth Article. The Preamble to the Constitution does refer to "God's protection" over the document's promulgation, but this is not legally taken as endorsement of belief in any deity. - ↑ In France the Concordat of 1801 made the Roman Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as Judaism.

- ↑ In Hungary the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the Roman Catholic, Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 Judaism was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.[65][66]

- ↑ In the Kingdom of Ireland the Church of Ireland was established in the Reformation.[67] The Act of Union 1800 created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with the United Church of England and Ireland established outside Scotland. The Irish Church Act 1869 demerged and disestablished the Church of Ireland,[67] and the island was partitioned in 1922. The Republic of Ireland's 1937 constitution prohibits an established religion.[68] Originally, it recognized the "special position" of the Roman Catholic Church "as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of the citizens", and recognized "the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Methodist Church in Ireland, the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland, as well as the Jewish Congregations and the other religious denominations existing in Ireland at the date of the coming into operation of this Constitution".[69] These provisions were deleted in 1973.[70]

- ↑ The Philippines was among several possessions ceded by Spain to the United States in 1898; religious freedom was subsequently guaranteed in the archipelago. This was codified in the Philippine Organic Act (1902), section 5: "... That no law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, and that the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed." A similarly-worded provision still exists in the present Constitution. Catholicism remains the predominant religion, wielding considerable political and cultural influence.

- ↑ Article 25 of the constitution states: "1. Churches and other religious organizations shall have equal rights. 2. Public authorities in the Republic of Poland shall be impartial in matters of personal conviction". Article 114 of the Polish March Constitution of 1921 declared the Roman Catholic Church to hold "the principal position among religious denominations equal before the law" (in reference to the idea of first among equals). The article was continued in force by article 81 of the April Constitution of 1935. The Soviet-backed PKWN Manifesto of 1944 reintroduced the March Constitution, which remained in force until it was replaced by the Small Constitution of 1947.

- ↑ The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution explicitly forbids the federal government from enacting any law respecting a religious establishment, and thus forbids either designating an official church for the United States, or interfering with State and local official churches — which were common when the First Amendment was enacted. It did not prevent state governments from establishing official churches. Connecticut continued to do so until it replaced its colonial Charter with the Connecticut Constitution of 1818; Massachusetts retained an establishment of religion in general until 1833.[75] As of 2010, Article III of the Massachusetts constitution still provided, "... the legislature shall, from time to time, authorize and require, the several towns, parishes, precincts, and other bodies politic, or religious societies, to make suitable provision, at their own expense, for the institution of the public worship of God, and for the support and maintenance of public Protestant teachers of piety, religion and morality, in all cases where such provision shall not be made voluntarily."[76] The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1868, makes no mention of religious establishment, but forbids the states to "abridge the privileges or immunities" of U.S. citizens, or to "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law". In the 1947 case of Everson v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court held that this later provision incorporates the First Amendment's Establishment Clause as applying to the States, and thereby prohibits state and local religious establishments. The exact boundaries of this prohibition are still disputed, and are a frequent source of cases before the U.S. Supreme Court — especially as the Court must now balance, on a state level, the First Amendment prohibitions on government establishment of official religions with the First Amendment prohibitions on government interference with the free exercise of religion. See school prayer for such a controversy in contemporary American politics. All current State constitutions do mention a Creator, but include guarantees of religious liberty parallel to the First Amendment. The constitutions of eight states (Arkansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas) also contain clauses that prohibit atheists from holding public office.[77][78] However, these clauses were held by the U.S. Supreme Court to be unenforceable in the 1961 case of Torcaso v. Watkins, where the court ruled unanimously that such clauses constituted a religious test incompatible with the religious test prohibition in Article 6 Section 3 of the United States Constitution. The Church of Hawaii was the state church of Hawaii from 1862–1893.

- ↑ The Church in Wales was split from the Church of England in 1920, by Welsh Church Act 1914; at the same time becoming disestablished.

See also

- List of state-established religions

- Confessional state

- Civil religion

- Political religion

- Separation of church and state

- Major religious groups

- Freedom of religion

- Status of religious freedom by country

- Religious toleration

- Secular state

- Secular religion

- Elite religion

- Cuius regio, eius religio

- Divine rule

Notes

References

- ↑ The Journal of Ecclesiastical History – Page 268 by Cambridge University Press, Gale Group, C.W. Dugmore

- ↑ The headship was administrative and jurisdictional but did not include the potestas ordinis (the right to preach, ordain, administer the sacraments and rites of the Church which were reserved to the clergy) –Bray, Gerald. Documents of the English Reformation James Clarke & Cº(1994), p.114

- ↑ Neill, Stephen. Anglicanism Penguin (1960), p.61

- ↑ The concerned religious communities are the dioceses of Metz and of Strasbourg, the Lutheran EPCAAL and the Reformed EPRAL and the three Israelite consistories in Colmar, Metz and Strasbourg.

- ↑ Super User. "Costa Rica Constitution in English - Constitutional Law - Costa Rica Legal Topics". costaricalaw.com.

- 1 2 Constitution Religion at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 March 2009) (archived from the original on 2009-03-26).

- ↑ "Constitution of Malta (Article 2)". mjha.gov.mt.

- ↑ CONSTITUTION DE LA PRINCIPAUTE at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 September 2011) (French): Art. 9., Principaute De Monaco: Ministère d'Etat (archived from the original on 2011-09-27).

- ↑ "Vatican City". Catholic-Pages.com. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "CONSTITUCION NACIONAL ARGENTINA". DIARIOS Y NOTICIAS DE ARGENTINA.

- ↑ "Argentina - Religión". argentina.gob.ar.

- ↑ Executive Summary - Panama, 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom, United States Department of State.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Paraguay".

The role played by the Catholic Church in the historical and cultural formation of the Republic is hereby recognized.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of Peru" (PDF).

Within an independent and autonomous system, the State recognizes the Catholic Church as an important element in the historical, cultural, and moral formation of Peru and lends it its cooperation. The State respects other denominations and may establish forms of collaboration with them.

- ↑ "The Constitution of the Republic of Poland". 1997-04-02.

The relations between the Republic of Poland and the Roman Catholic Church shall be determined by international treaty concluded with the Holy See, and by statute. The relations between the Republic of Poland and other churches and religious organizations shall be determined by statutes adopted pursuant to agreements concluded between their appropriate representatives and the Council of Ministers.

- 1 2 3 THE CONSTITUTION OF GREECE: SECTION II RELATIONS OF CHURCH AND STATE: Article 3, Hellenic Resources network.

- 1 2 THE CONSTITUTION OF GREECE: PART TWO INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL RIGHTS: Article 13

- ↑ Constitution of Georgia Article 9(1&2) and 73(1a1)

- ↑ "The History of the Church of England". The Archbishops' Council of the Church of England. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ↑ "2010 Report on International Religious Freedom - Tuvalu", United States Department of State

- ↑ Constitution of Tuvalu, article 23.

- ↑ Denmark – Constitution: Section 4 State Church, International Constitutional Law.

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Iceland: Article 62, Government of Iceland.

- ↑ The Constitution of Norway, Article 16 (English translation, published by the Norwegian Parliament)

- ↑ Løsere bånd, men fortsatt statskirke, ABC Nyheter

- ↑ Staten skal ikke lenger ansette biskoper, NRK

- ↑ Human-Etisk Forbund. "Ingen avskaffelse: / Slik blir den nye statskirkeordningen". Fritanke.no.

- ↑ Offisielt frå statsrådet 27. mai 2016 regjeringen.no «Sanksjon av Stortingets vedtak 18. mai 2016 til lov om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.) Lovvedtak 56 (2015-2016) Lov nr. 17 Delt ikraftsetting av lov 27. mai 2016 om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.). Loven trer i kraft fra 1. januar 2017 med unntak av romertall I § 3 nr. 8 første og fjerde ledd, § 3 nr. 10 annet punktum og § 5 femte ledd, som trer i kraft 1. juli 2016.»

- ↑ Lovvedtak 56 (2015–2016) Vedtak til lov om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.) Stortinget.no

- ↑ Finland – Constitution, Section 76 The Church Act, http://servat.unibe.ch/icl/fi00000_.html.

- ↑ "Status of the Finnish State Church in 2007—Privileges of the State Church". eroakirkosta.fi. 7 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Eroakirkosta.fi - Palvelun tavoite: Kirkko on erotettava valtiosta

- ↑ Cecilia Olla (12 June 2014). "Framtidens folkbokföring efter distrikt istället för församling" (in Swedish). Swedish National Heritage Board. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ "Church-state tie opens door for mosque". New York Times. 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

- ↑ Hungary's Constitution of 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ Constitution of Zambia. REtrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "THE CONSTITUTION OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH (As modified up to 17 May, 2004)". parliament.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06.

- ↑ Secularism is back in Bangladesh, rules High Court http://www.deccanherald.com/content/102192/secularism-back-bangladesh-rules-high.html

- ↑ FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/sections_detail.php?id=367§ions_id=24560

- ↑ "International Religious Freedom Report for 2012 - Djibouti". Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ "Part I: "Introductory"". Pakistani.org. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Constitution of Cambodia". cambodia.org. Retrieved 2011-04-13. (Article 43).

- ↑ "Chapter II — Buddhism". The Constitution of the Republic of Sri Lanka. The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 2007-10-18.fv

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Section 361: Buddhism as Majority Religion". berkleycenter.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ↑ "Draft of Tsa Thrim Chhenmo" (PDF). www.constitution.bt. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- Article 3, Spiritual Heritage

- Buddhism is the spiritual heritage of Bhutan, which promotes the principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance.

- The Druk Gyalpo is the protector of all religions in Bhutan.

- It shall be the responsibility of religious institutions and personalities to promote the spiritual heritage of the country while also ensuring that religion remains separate from politics in Bhutan. Religious institutions and personalities shall remain above politics.

- The Druk Gyalpo shall, on the recommendation of the Five Lopons, appoint a learned and respected monk ordained in accordance with the Druk-lu, blessed with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished in ked-dzog, as the Je Khenpo.

- His Holiness the Je Khenpo shall, on the recommendation of the Dratshang Lhentshog, appoint monks blessed with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished in ked-dzog as the Five Lopons.

- The members of the Dratshang Lhentshog shall comprise:

(a) The Je Khenpo as Chairman;

(b) The Five Lopons of the Zhung Dratshang; and

(c) The Secretary of the Dratshang Lhentshog who is a civil servant. - The Zhung Dratshang and Rabdeys shall continue to receive adequate funds and other facilities from the State.

- Article 3, Spiritual Heritage

- ↑ Trouble in Utopia: The Overburdened Polity of Israel, by Dan Horowitz and Moshe Lissak, p51-52

- ↑ International Religious Freedom Report 2009 : Israel and the occupied territories, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- ↑ Gentile, Emilio (2006) [2001]. Le religioni della politica. Fra democrazie e totalitarismi [Politics as Religion]. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Internal Revenue Service. "Tax guide for churches and Religious Institutions" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ↑ Internal Revenue Seervice. "Exemption Requirements". United States Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1938). "Local and National Houses of Justice". The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 7. ISBN 0-87743-231-7.

- ↑ "The Theodosian Code". THE LATIN LIBRARY at Ad Fontes Academy. Ad Fontes Academy. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ↑ Halsall, Paul (June 1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ↑ "Confucian Religiosity: A Partial Bibliography".

- ↑ History of civilizations of Central Asia.: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Part two : The achievements, p59

- ↑ Medieval Persia 1040–1797, David Morgan p.72

- ↑ https://www.denederlandsegrondwet.nl/9353000/1/j9vvihlf299q0sr/vi6ei64fdgg2

- ↑ https://www.denederlandsegrondwet.nl/9353000/1/j9vvihlf299q0sr/vi6jejckwezy

- ↑ http://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/14622151/Deontknopingvandezilverenkoorde21.pdf!null

- ↑ http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0003640/1994-01-01

- ↑ "The Roots of Religious Liberty". Rights of the People: Individual freedom and the Bill of Rights. US State Department. December 2003. Archived from the original on 2004-06-03. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

- ↑ See History of the Connecticut Constitution.

- ↑ Struggle For Statehood Edward Leo Lyman, Utah History Encyclopedia

- ↑ John Gunter, Inside Latin America (1941), p. 166

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Hungary at the Wayback Machine (archived 20 February 2008) (archived from the original on 2008-02-20)

- ↑ The right of thought, the freedom of conscience and religion –Hungary.hu at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 May 2007) (archived from the original on 2007-05-23)

- 1 2 Livingstone, E. A.; Sparks, M. W. D.; Peacocke, R. W. (2013-09-12). "Ireland". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 286. ISBN 9780199659623. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ "CONSTITUTION OF IRELAND". Irish Statute Book. pp. Article 44. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Keogh, Dermot; McCarthy, Dr. Andrew (2007-01-01). The Making of the Irish Constitution 1937: Bunreacht Na HÉireann. Mercier Press. p. 172. ISBN 9781856355612.

- ↑ "Fifth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1972.". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Andrea Mammone; Giuseppe A. Veltri (2010). Italy today: the sick man of Europe. Taylor & Francis. pp. 168 (Note 1). ISBN 978-0-415-56159-4.

- ↑ Luxembourg

- ↑ Under the 1967 Constitution, Roman Catholicism was the state religion as stated in Article 6: "The Roman Catholic Apostolic religion is the state religion, without prejudice to religious freedom, which is guaranteed in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution. Official relations of the republic with the Holy See shall be governed by concordats or other bilateral agreements." The 1992 Constitution, which replaced the 1967 one, establishes Paraguay as a secular state, as mentioned in section (1) of Article 24: "Freedom of religion, worship, and ideology is recognized without any restrictions other than those established in this Constitution and the law. The State has no official religion."

- ↑ The modern Church of Scotland has always disclaimed recognition as an "established" church. The Church of Scotland Act 1921 formally recognised the Kirk's independence from the state.

- ↑ James H. Hutson (2000). Religion and the new republic: faith in the founding of America. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 22. ISBN 978-0-8476-9434-1.

- ↑ CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS, malegislature.gov.

- ↑ "State Constitutions that Discriminate Against Atheists". www.godlessgeeks.com. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Religious laws and religious bigotry – Religious discrimination in U.S. state constitutions". www.religioustolerance.com. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

Further reading

- Rowlands, John Henry Lewis (1989). Church, State, and Society, 1827-1845: the Attitudes of John Keble, Richard Hurrell Froude, and John Henry Newman. Worthing, Eng.: P. Smith [of] Churchman Publishing; Folkestone, Eng.: distr. ... by Bailey Book Distribution. ISBN 1-85093-132-1

External links

- McConnell, Michael W. (April 2003). "Establishment and Disestablishment at the Founding, Part I: Establishment of Religion". William and Mary Law Review, provided by Questia.com. 44 (5): 2105. Retrieved 2006-11-23.