Libretto of The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute is a celebrated opera composed in 1791 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart employed a libretto written by his close colleague Emanuel Schikaneder, who was also the director of the Theater auf der Wieden at which the opera premiered in the same year. (He played the role of Papageno as well). Grout and Williams describe the libretto thus:

Schikaneder, a kind of literary magpie, filched characters, scenes, incidents, and situations from others' plays and novels and with Mozart's assistance organized them into a libretto that ranges all the way from buffoonery to high solemnity, from childish faerie to sublime human aspiration – in short from the circus to the temple, but never neglecting an opportunity for effective theater along the way.[1]

Sources

The sources for the work fall into (at least) four categories: works of literature, earlier productions of Schikaneder's theater company, Freemasonry, and the 18th century tradition of popular theater in Vienna.

Literary sources

- In work with D. D. Roy Owen, Peter Branscombe notes strong resemblances between the opening scenes of The Magic Flute and episodes of the medieval romance Yvain by Chrétien de Troyes (c. 1177). This work attracted attraction in Mozart and Schikaneder's time and appeared in a 1786–7 German translation by K. J. Michaeler, a member of the same Masonic lodge as Mozart. Yvain offers the following possible models: an imperiled hero in a desolate countryside, carrying a bow and rendered unconscious, is rescued by three ladies, who bring him to a high-born mistress who is in need of a hero's services. In another scene of Yvain (which Owen and Branscombe suggest Schikaneder conflated with the first), the hero encounters a sort of wild man in dress so outlandish that he doubts his humanity; like Papageno, this wild man must assure the hero that he is human.[2]

- A major source appears to have been the 1731 novel Sethos ("Life of Sethos, taken from private memoirs of the ancient Egyptians") by the French author Jean Terrasson. The work appeared in a German translation by Matthias Claudius in 1777–8. Branscombe sees this a possible source for the serpent that appears in the opening scene, for the trials of water and fire, for the words sung by the Two Armed Men, and for the text of Sarastro's hymn "O Isis und Osiris." The connection is sufficiently close that Branscombe even suggests that modern directors attempting a new production should consult Sethos carefully for the hints it provides concerning what Mozart and Schikaneder would have wanted in terms of production and stage design.[3]

- The long essay "Über die Mysterien der Ägypter" ("On the mysteries of the Egyptians"), published by the Vienna scientist and Freemason Ignaz von Born in the first issue of the Masonic journal Journal für Freymaurer in 1784. This work describes among other things the worship of Isis and Osiris, the gods to whom Sarastro and his priests pray. It also is a possible source for the passages of overt misogyny, discussed below, that often perturb modern readers of Schikaneder's libretto.[4]

- The series of three books entitled Dschinnestan published by Christoph Martin Wieland in 1786 to 1789 contains a total of 19 fairy tales. Some of these are retold stories, others were made up by Wieland or by his collaborator J. A. Liebeskind. Various of these stories – which were being separately published in Vienna at the time The Magic Flute was being written – are held to have influenced Schikaneder's Magic Flute libretto.

- "Adis und Dahy" contains a model for the character Monostatos; he is a black slave who watches over the heroine and is later punished by his master.[5]

- "Neangir und seine Brüder" ("Neangir and his brothers") provides a model for Tamino's famous aria "Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön": a hero falls in love with a woman merely by seeing her portrait and sets off to rescue her. As Branscombe notes, this situation is common enough in literature, but "Neangir" contains many of the actual words used in the text Schikaneder wrote for this aria.[6]

- "Die klugen Knaben" ("The clever boys") is perhaps the model for the Three Boys. They give wise advice to characters in the story, including a somewhat more verbose version of Schikaneder's "Sei standhaft, duldsam, und verschwiegen" ("Be steadfast, resolute, and discreet"). They also descend from the skies "on a white shining cloud to prevent a tragic outcome", perhaps the model for the Three Boys' interventions to prevent the intended suicides of Pamina and Papageno.[7]

- "Lulu, oder die Zauberflöte" ("Lulu, or the Magic Flute"). Branscombe takes the view that this story provided little more than the title of the opera.

Earlier theatrical productions

The Schikaneder troupe prior to the premiere of The Magic Flute had developed considerable experience with performing fairy tale operas with similar plots, characters, and singers. Two bear a particularly strong relationship to The Magic Flute:

- Oberon, a romantic Singspiel in five acts by Friederike Sophie Seyler, premiered in a plagiarized version by Karl Ludwig Giesecke, later the first First Slave in The Magic Flute. Its source is a verse epic of the same title by Wieland.[8]

- Der Stein der Weisen oder Die Zauberinsel, premiered 1790. This, too, was based on a source in Wieland's Dschinnestan".[8]

Freemasonry

A very long tradition asserts that Freemasonry plays a major role in the content of Schikaneder's libretto.[9] Mozart was an active Mason in Vienna, and wrote a substantial quantity of music for his own lodge, including in 1791 (see Mozart and Freemasonry). Schikaneder had been a Mason in Regensburg (1786–7) for a few months before his lodge suspended him.[10]

The simpler accounts of Masonic influence in The Magic Flute assume that Masonry provided a system of values, symbolism, and ritual for the opera, but no part of the narrative. More elaborate accounts suggest that the opera was intended as an allegory with a hidden Masonic agenda. For instance, the evil Queen of the Night is sometimes taken to be an emblem for the empress Maria Theresa, who was hostile to Freemasonry in Austria during her reign (1740–1780).

It remains a near-consensus that the opera is in a sense Masonic. However, the Mozart scholar David J. Buch has expressed a contrarian view, suggesting that Masonic interpretations have been oversold. His key point is that careful study of some of the other possible sources, such as those mentioned above, provides alternative origins for elements of the libretto thought to be Masonic. Buch is particularly skeptical of allegorical Masonic interpretations, since libretti with such hidden agendas do not appear to have been commonly created in Mozart and Schickaneder's day.[11]

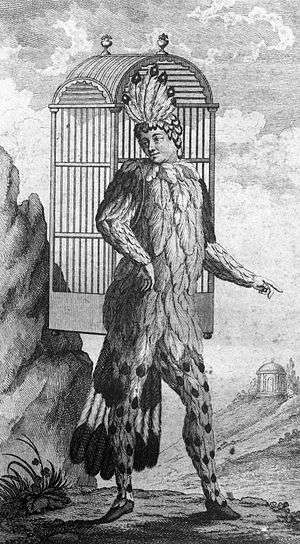

Viennese popular theater

The Hanswurst character was a mainstay of the popular theater tradition in Vienna, dating back decades before 1791. This character is earthy, wily, and charming, and Papageno survives in modern times as the best known representative of his type. During the period that the Schikaneder troupe was successfully mounting fairy tale operas, it also produced a series of musical comedies featuring Schikaneder in a Hanswurst-like role. These consisted of Der Dumme Gärtner aus dem Gebirge, oder Die zween Antons ("The Foolish Gardener from the Mountains, or The Two Antons"), premiered in July 1789, and a series of five sequels.[12] Mozart himself enjoyed attending these comedies, as a letter to his wife Constanze attests.[13]

Viennese popular theater in this tradition often included improvisation, and there is evidence that Schikaneder may have improvised some of his part when he premiered the role of Papageno. For instance, when Mozart played a practical joke on him during his performance of "Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen", Schikaneder quickly went off-script and turned the joke to his own advantage. Mozart related the story in a letter to his wife:

Today I had such a yen to play the Glockenspiel myself I went on stage. Just for fun, at the point where Schikaneder has a pause, I played an arpeggio. He was startled, looked into the wings and saw me. When he had his next pause I played no arpeggio. This time he stopped and refused to go on. I guessed what he was thinking and again played a chord. He then struck the magic bells and said, "Shut up!" This made everyone laugh.[14]

The physical comedy that was an element of Viennese popular theater is called for directly at one point in the libretto. The opening eight bars of orchestral introduction to the duet "Pa pa pa", at the moment when Papagena is revealed to Papageno as his future wife, includes the stage direction that Papageno and Papagena "both engage during the ritornello in comic play."[15]

Mozart's background

The experiences and background of the composer, who liked to have considerable input into the libretto (see The Abduction from the Seraglio for testimony), are also relevant.

- Mozart is known to have visited the Temple of Isis at Pompeii in 1769, just a few years after it was unearthed and when Mozart was himself just 13 years old. His visit and the memories of the site are considered to have inspired him 20 years later in his composition of The Magic Flute.[16]

- The play Thamos, King of Egypt by Tobias Philipp von Gebler, with themes similar to those in The Magic Flute, premiered in Vienna in 1774. Between 1773 and 1780, Mozart wrote incidental music, K. 345/336a, for this work.

Didactic poetry

Nedbal writes, "Moral maxims appear frequently in eighteenth-century German drama and contemporary German theorists of theater often discuss them in their treatises. The main function of maxims is to draw a generalized observation from the proceedings on stage in order to promote virtue or condemn vice."[17] Cairns attributes a taste for "didactic sentiment" specifically to the Viennese popular theater.[18] Concerning The Magic Flute specifically, Rosen writes that it "develops ... a conception of music as a vehicle for simple moral truths."[19] The opera's didacticism is concentrated in passages of poetry, set in the ensemble scenes, in which the characters cease to converse with each other and join in singing an edifying lesson to the audience.

.jpg)

One example is found in the first act, just after Monostatos and his slaves dance peaceably off the stage, enchanted by Papageno's magic bells and leaving Pamina and Papageno in freedom.[20] The two celebrate their escape by singing the following.

Könnte jeder brave Mann |

Could but every brave man |

The second act finale begins with a scene framed by didactic poetry.[21] First the Three Boys enter, singing:

Bald prangt, den Morgen zu verkünden, |

Soon, to herald the morning, |

.jpg)

The action then shifts to drama and dialogue: the Three Boys find Pamina in despair in the belief that Tamino has abandoned her, and she nearly commits suicide. The Three Boys succeed in dissuading her, explaining that Tamino truly loves her and indeed is willing to risk death for her. Pamina, once convinced, ardently sings "Ich möcht' ihn sehen" ("I want to see him") five times; then after a brief pause the four characters sing:

Zwei Herzen, die von Liebe brennen, |

Two hearts that burn with love |

Rosen suggests that not just the words of these passages, but even the music is didactic: "The morality of Die Zauberflöte is sententious, and the music often assumes a squareness rare in Mozart, along with a narrowness of range and an emphasis on a few notes very close together that beautifully illuminate the middle-class philosophy of the text." As an example Rosen cites the music for the passage beginning "Könnte jeder brave Mann", cited above.[22]

The didactic passages in Schikaneder's libretto attracted the admiration of Franz Liszt, who after attending a performance copied down several of them in a personal letter.[23] Ingmar Bergman in his 1975 film of the opera gave special treatment to the didactic poetry by having his characters hoist "a series of placards on which these moral sentiments are carefully lettered."[24]

The passage quoted above beginning "Zwei Herzen" has attracted particular admiration: Heartz called it "the loveliest of all the opera's beautiful moments";[25] Abert wrote of "a paradisal radiance unique in this work".[26] Liszt quoted Schikaneder's verse in his letter and appended, "Amen!".

Sexism and misogyny

A matter that perturbs many who encounter the opera is sexism and misogyny, particularly as expressed by the priests of Sarastro's order. (Racism, as expressed in the character of Monostatos, is also a matter of wide concern.)

Many critics have weighed in this question. Branscombe (1991), though deploring these elements in the libretto, might nevertheless be considered to represent something of an apologist view. Hunter (2008:109) offers a middle-of-the-road course, and Brown-Montesano (2007) provides a consistent and forcefully-expressed refutation of the apologists.[27] David Cairns takes yet another view, one that distinguishes Schikaneder's contributions from Mozart's. In Cairns's judgment, Schikaneder himself was an unredeemable sexist, in addition to being (as the historical record indicates; see Emanuel Schikaneder) a womanizer: "Schikaneder appreciated women, no doubt of that, but not exactly in a spirit of emancipation." But Mozart, according to Cairns, consistently worked at improving the libretto in this respect, by omitting the worst of what Schikaneder wrote and more generally by enriching and enobling the character of Pamina. The elevation of Pamina's character indeed matches Mozart's lifelong practice, as Cairns suggests:

How could Mozart have done otherwise? [His portrayal of Pamina] is one more example of the thread that runs through the operas – what Daniel Heartz has called Mozart's "infinite care to create strong and deeply moving female characters in [...] all of his operas."[28]

Authorship

Mainstream scholarship views Schikaneder as the highly probable author. For a marginally-supported alternative candidate, see Karl Ludwig Giesecke.

Assessment

It is not uncommon for critics to describe the libretto of The Magic Flute as being of dreadful quality. Thus Bauman writes, "The libretto has been generally regarded, in Dent's words, as "one of the most absurd specimens of that form of literature [i.e. libretti] in which absurdity is regarded as matter of course."[29] With occasional exceptions, critics voice harsh views on the quality of Schikaneder's German versification as well. Such critics generally do not defend it on its own terms (as if it could stand independently as a work of theater), but rather as a vehicle that served as a great inspiration for Mozart for composition, particularly in its assertion of high ideals and the portrayal of selfless love in the characters of Pamina and Tamino. The harsh assessment is not universal; see for instance the quotation with which this article begins. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe admired the work sufficiently to undertake writing a sequel.

See also

- Belmont und Constanze. Sources for another Mozart opera.

- Vestas Feuer. A libretto Schikaneder prepared for Ludwig van Beethoven.

Notes

- ↑ Donald Grout and Hermine Weigel Williams (2003) A Short History of Opera. New York: Columbia University Press. Page 327. Extracts on line at Google Books:

- ↑ D. D. Roy Owen and Branscombe, in Branscombe (1991:7–10)

- ↑ Branscombe (1991:10–18)

- ↑ Branscombe (1991:21–25)

- ↑ Branscombe (1991:26)

- ↑ Branscombe (1991:26)

- ↑ Branscombe (1991:27)

- 1 2 Branscombe (1991:28)

- ↑ A major reference is Chailley (1972). A review sharply attacking the quality of scholarship in Chailley's book is "P. J. B." (1972).

- ↑ Branscombe (1991:43–44)

- ↑ Buch (2004)

- ↑ Clive (1993, 136)

- ↑ "Yesterday I attended the second part of Una Cosa Rara but it didn't please me as much as the Antons." (“gestern war ich in dem zweÿten theil von der Cosa rara — gefällt mir aber nicht so gut wie die Antons.”). See W. A. Mozart. Briefe und Aufzeichnungen, ed. Wilhelm A. Bauer, Otto Erich Deutsch and Joseph Heinz Eibl, 7 vols. (Kassel, 1962–75), IV, 110 (No. 1129)

- ↑ Quoted from the English translation of Heartz (1990:267), who also provides the original German.

- ↑ German "beide haben unter dem Ritornell komisches Spiel". The page on the online NMA edition is .

- ↑ The Magic Flute, Matheus Franciscus & Maria Berk, p. 450, Brill, 2004, ISBN 90-04-13099-3

- ↑ See Nedbal (2009:125), who uses this fact as a caution to those who would interpret the didactic passages of The Magic Flute as intended ironically.

- ↑ Cairns (2006, 202)

- ↑ Rosen (1997:319)

- ↑ NMA score:

- ↑ In the NMA edition the scene begins on p. 267: .

- ↑ Rosen (1997:319)

- ↑ Letter to Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, 23 July 1857. See La Mara (ed.) Franz Liszt's briefe, Volume 4, Breitkopf & Härtel, 1900, p. 380. Viewable on line at Google Books: /

- ↑ Duncan (2004:239), part of an extended analysis and appreciation of Bergman's filmed version. See Nedbal (2009) for a much less sympathetic view of Bergman's placards.

- ↑ Heartz (2009:283)

- ↑ See Abert (1920/2007:1290), who discusses the scene in detail.

- ↑ Hunter, Mary (2008) Mozart's Operas: A Companion, New Haven:Yale University Press. Brown-Montesano, Kristi (2007) Understanding the Women of Mozart's Operas, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- ↑ Cairns reference: David Cairns (2006) Mozart and His Operas. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. The quotation is from page 210.

- ↑ Bauman, Thomas (1990) "At the north gate: instrumental music in Die Zauberflöte. In Heartz, Daniel (1990) Mozart's operas. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

References

- Abert, Hermann (1920/2007) W. A. Mozart. Revised 2007 edition, translated by Stewart Spencer and with commentary by Cliff Eisen. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Branscombe, Peter (1991) W. A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521319164

- Buch, David J. (2004) "Die Zauberflöte, masonic opera, and other fairy tales". Acta Musicologica 76:193–219. Available on line: .

- Cairns, David (2006) Mozart and His Operas. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Quoted material accessible on line at Google Books: .

- Chailley, Jacques (1972) The Magic Flute, Masonic Opera, translated from the original French by Herbert Weinstock. London: Gollancz.

- Clive, Peter (1993) Mozart and his Circle: A Biographical Dictionary. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Duncan, Dean (2004) Adaptation, enactment, and Ingmar Bergman's Magic Flute. BYU Studies 43:229–250. Available on line:

- Heartz, Daniel (1990) Mozart's Operas. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. The quoted section may be accessed on line at Google Books:

- Heartz, Daniel (2009) Mozart, Haydn and Early Beethoven, 1781–1802. New York: W. W. Norton. The quoted passage may be viewed on line at Google Books: .

- Nedbal, Martin (2009) Mozart as a Viennese moralist: Die Zauberflöte and its maxims. Acta Musicologica 81:123–157.

- Rosen, Charles (1997) The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. New York: Norton.

- "P. J. B. [Slater]" (1972) Review of Chailley (1972). Music & Letters, Vol. 53, No. 4 (October), pp. 434–436. On line at JSTOR: .