Vestas Feuer

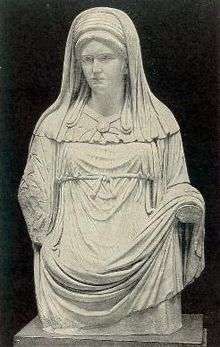

Vestas Feuer ("The Vestal Flame"[1]) is a fragment of an opera composed in 1803 by Ludwig van Beethoven to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The plot involves a romantic intrigue in which the heroine temporarily becomes a Vestal Virgin (a keeper of the Vestal Flame in Ancient Rome.) Beethoven set to music only the first scene of Schikaneder's libretto, then abandoned the project. The fragment (about ten minutes of music) is rarely performed.

Background

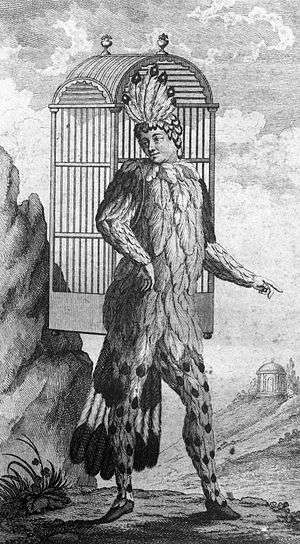

Emanuel Schikaneder (1751-1812) was not just a librettist but also an actor, singer, playwright, and theater director. He had already achieved a form of immortality in 1791 by authoring the libretto of (and generally sponsoring) Mozart's opera The Magic Flute, a tremendous success at its premiere and still an important part of his company's repertoire. According to Lockwood The Magic Flute was an opera that Beethoven "loved ... and knew like the back of his hand".[2] In 1801, Schikaneder's company had abandoned the Theater auf der Wieden in which The Magic Flute had premiered, and moved into a larger and grander theater he had built, the Theater an der Wien. This theater was well suited to Schikaneder's preference for theatrical spectacle, with elaborate scenery and stage effects. The theater opened with an opera about Alexander the Great, composed by Franz Teyber; the libretto had been offered by Schikaneder first to Beethoven, who had declined it.[3]

By 1803, the year of his Beethoven collaboration, the 51-year-old Schikaneder was already seeing his career go into decline (ultimately, it collapsed entirely), but at the time he was still an important figure in the Viennese theatrical and musical scene.[4] "Vestas Feuer" was his last libretto.[5]

For Beethoven, 1803 was a pivotal year.[6] He was 32, and during the eleven years he had spent in Vienna he had already established himself as a leading composer. He had recently begun an important shift in his compositional methods and goals, a shift that emphasized the musical portrayal of heroism and led to what today is often called his Middle Period. Already completed were important new works such as the Op. 31 piano sonatas,[7] and on his desk were massive new works representing the Middle Period in full flower: the Waldstein Sonata and the Third Symphony.

Schikaneder and Beethoven's collaboration

Beethoven's collaboration with Schikaneder was only the latest in a series of experiences he had had since arriving in Vienna in 1792 paralleling the life experiences (patrons, colleagues, performing venues, travel itineraries) of Mozart, who had died in 1791; for discussion see Mozart and Beethoven.

During the years he spent at the Theater auf der Wieden, Schikaneder had found it efficient to live where he worked; i.e. in the same apartment complex that included the theater; many of his colleagues lived there too. Schikaneder made sure he could continue this practice by incorporating into the new Theater an der Wien a four-story apartment house where he and a number of members of his theatrical company dwelt.

In early 1803 Schikaneder made another attempt to collaborate with Beethoven: he asked him to compose an opera for his theater, providing as a partial incentive free housing in the apartment complex. Beethoven agreed and moved into the complex, where he was to live from about April 1803 to May 1804, apart from some summer visits (his custom) to nearby rural locations in Baden and Oberdöbling. Beethoven's younger brother Johann, who was acting as his business manager at the time, also moved into one of the theater's apartments. Beethoven scheduled a concert of his works for the theater in April; and the theater was to continue as a favored venue for him.[8]

At first Beethoven was free of any obligations in the collaboration, since Schikaneder did not finish his libretto for Beethoven until late October. Beethoven was in event fully occupied with composing other works (see above).[3] He began work on Vestas Feuer in late November and kept at it for about a month.[4]

Plot and musical structure

Lockwood summarizes the plot of Vestas Feuer thus:

The plot centers on the heroine Volivia and her lover Sartagones, "a noble Roman," whose father is Porus's sworn enemy. Intrigues are hatched by the jealous slave Malo and by other characters led by Romenius, a Roman official. Romenius also loves Volivia and, for her, has abandoned his former lover, Sericia. Romenius manages to banish both Porus and Sartagones from Rome. Volivia seeks refuge from Romenius's advances by becoming a priestess in the Temple of Vesta, thus giving Romenius and his soldiers a reason to destroy the temple -- whereupon the sacred flame is extinguished. After various episodes, including the reappearance of Porus and Sartagones, Romenius has Malo drowned in the Tiber but is himself stabbed by his jealous lover Sericia. When all the evildoers are dead, the sacred flame miraculously reignites itself, the Vestal Virgins rejoice, and Volivia is reunited with Sartagones and Porus amid general rejoicing.[9]

The first scene was the only one set by Beethoven. The setting for this scene was given thus by Schikaneder:

The theater [i.e. stage ] is an enchanting garden of cypresses; a waterfall gushes forth in the center and runs into a brook at the right. On the left is a tomb with several steps leading down. Dawn is shining through the trees.[10]

Lockwood gives the action of the scene:

Malo has been spying on the lovers, Volivia and Sartagones, and he rushes on to tell Porus he has seen them together, presumably all night since it is not morning. Porus is furious, because he hates Sartagones, and declares he will disown his daughter. ... Porus and Malo hide as the lovers appear. Now Sartagones and Volivia swear to love each other, but she anxiously begs Sartagones to ask her father's blessing, assuring him that Porus is good hearted. Porus suddenly emerges and confronts Sartagones, evoking their ancient family feud. Volivia pleads, but Porus is adamant. Then Sartagones draws his sword, asking "Will not she be mine?" Porus refuses, whereupon Sartagones points the sword at his own breast. But Porus, whose anger turns in a flash to sympathy, strikes the sword at once from Sartagones's hand, singing with Volivia, "Halt ein!" ["Stop!"] ... Now Porus immediately turns magnanimous, ... declaring "Since you love her so much, I will bestow her upon you" and affirms his friendship with Sartagones. Malo, upset by all this, leaves the stage, whereupon the three main characters -- the father and the two lovers -- close the first scene in a joyful trio of mutual affection.[11]

As Lockwood notes, Beethoven set this stage action in four musical sections, with keys as noted:

- G minor: dialog of Malo and Porus

- E flat major: love duet of Volivia and Sartagonese

- C minor: "accompanied dialog recitative: confrontation of Sartagones and Porus, ending in their reconciliation"

- G major: final trio

The scoring of the work is for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, and strings.[12]

Influences of Mozart

Beethoven's music for Vestas Feuer sounds unmistakably Beethovenian, indeed, characteristic of the emerging Middle Period of his career. Yet clear influences from Mozart have nonetheless been discerned. Lockwood hears in the "Halt ein!" portion of the scene Beethoven set an echo of 'a parallel moment in The Magic Flute in which Papageno is saved by intervention of the Three Boys from suicide. The love duet between Volivia and Sartagones, in E flat major and 6/8 time, evokes Mozart's "Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen" (sung by Pamina and Papageno in The Magic Flute), which has the same key and time signature and was the subject of a set of variations for cello and piano by Beethoven (WoO 46),[13] written 1801.[14]

Lockwood also discerns a precedent set by Mozart involving formal structure: an Introduzione; i.e. Beethoven's scene forms a separable initial section of an opera having some degree of integrity of both plot and harmonic plan; Lockwood calls the Introduzione a "miniplay". Three of Mozart's operas begin with such an Introduzione: Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, and The Magic Flute.[15] Beethoven's Introduzione has a harmonic structure echoing that of The Magic Flute. The downward sequence of keys given above (g minor, E flat major, c minor, G major) echoes the upward sequence of similar keys in the Introduzione section of The Magic Flute: c minor, E flat major, G major, C major.[13]

Nedbal (2009) notes that Beethoven emphasizes moral over personal aspects of the libretto, an echo of the overt moralizing seen throughout The Magic Flute. In contrast, Joseph Weigl's setting of the same words (see below) emphasizes the feelings and experience of the characters.

Abandoning the project

Beethoven eventually felt as intolerable both the Vestas Feuer libretto and the task of collaborating with Schikaneder, and he dropped the project. He expressed his opinions in a letter to Johann Friedrich Rochlitz:

I have finally broken with Schikaneder, whose kingdom has been entirely eclipsed by the light of the clever and thoughtful French operas. Meanwhile he has held me back for fully six months, and I have let myself be deceived simply because, since he is undeniably good at creating stage effects, I hoped that he would produce something more clever than usual. How wrong I was. I hoped at least that he would have the verses and the contents of the libretto corrected and improved by someone else, but in vain. For it was impossible to persuade this arrogant fellow to do this. Well, I have given up my arrangement with him, although I had composed several numbers. Just picture to yourself a Roman subject (of which I had been told neither the scheme nor anything else whatever) and language and verses such as could come out of the mouths of our Viennese women apple-vendors.[16]

Lockwood speculates that Beethoven must have felt some empathy at this stage with the long-dead Mozart, who unlike him had managed to bring his Schikaneder collaboration to a successful conclusion.

Vestas Feuer as embryonic Fidelio

Early in 1804, after dropping Vestas Feuer, Beethoven began work on a different opera, then entitled Leonora;[3] which ultimately became Fidelio, now a cornerstone of the repertory. Lockwood explains why the Leonora libretto was everything to Beethoven that the Vestas Feuer libretto was not:

Giving up on Schikaneder's feeble libretto after two months, Beethoven turned gratefully to a drama that offered characters and actions he could take seriously: Leonore, Florestan, Pizarro, and his underling Rocco, along with the profoundly moving chorus of suffering political prisoners, confined in Pizarro's dungeons, who yearn for the light that symbolizes freedom. At the end appears the benevolent minister Don Fernando, who resolves all troubles. All these individuals, bearer of meanings far beyond operatic plots and intrigues, embody authentic human issues in way that permitted Beethoven to integrate operatic conventions into his moral vision.[17]

As there was no likelihood of any performance of the single scene of Vestas Feuer that he had composed, Beethoven was free to turn its music to other purposes. In particular, the final trio, in which Volivia and Sartagones celebrate their love (with the blessing of Volivia's father Porus) is audibly a first draft of the duet "O namenlose Freude", between the reunited Leonora and Florestan, a climactic point in the plot of Fidelio. Lockwood says of the Vestas Feuer version that is "is on a much higher level than all that has preceded it [in the scene Beethoven wrote]".[18]

Beethoven also made sketches for a second scene, which evidently was never fully composed. Musicologist Alan Gosman indicates that these sketches included "a solo aria for Malo ... reused ... for Pizarro’s Aria with chorus 'Ha! Welch’ ein Augenblick!' in Fidelio.[19] Both characters are villains.

Aftermath

Schikaneder did not give up on his libretto but offered it to Joseph Weigl, who set it to music in full; this opera was performed at the Theater an der Wien—by then no longer under Schikaneder's direction—in August 1805.[20] It disappeared from the repertory following a run of 15 performances[21] and was never published.[22]

For Schikaneder the events of the time were the beginning of the end. Jan Swafford narrates

... a shake-up that resolved Beethoven's sticky contract situation with his nominal employer and ex-librettist Schikaneder. In the beginning of 1804, Baron Peter Anton Braun, who managed both court theaters,[23] bought the Theater an der Wien. Shortly after, Braun fired Schikaneder as director of the theater, whose statue as Papageno presided over the entrance. At that point Beethoven's contract with Schikaneder for an opera was terminated, and he had to move out of the theater. That solved the friction over Vestas Feuer, but it was a setback for Leonore. Beethoven had been going at the opera full tilt ...[24]

The rest of Schikaneder's life involved a brief period rehired at the Theater an der Wien, followed by a period of playing the provinces, insanity, poverty, and his death in 1812 at age 61.

Critical assessment

In assessing Schikaneder's libretto, modern critics tend to agree with Beethoven (see above). Lockwood, in his Beethoven biography, calls it "a mediocre piece of hackwork."[25] Barry Cooper describes it as "lamentable."[26] Paul Robinson, after noting an old letter indicating that Beethoven was looking for a "reasonable text" says:

Vestas Feuer is not a reasonable text. It is a ponderously heroic affair set in ancient Rome (though the names of the characters suggest Parthia or India) and replete with tedious intrigue. Schikaneder had lapsed from pantomime into the stagnant backwash of Metastasio while retaining (in Beethoven's words to Rochlitz) 'language and verses such as could only proceed out of the mouths of our Viennese apple-women.'[27]

Westermann (1983) evidently finds the first scene tolerable but goes on to say, "from here on the text deteriorates into a quagmire of complicated theatricality which Beethoven did well to abandon."[28]

In contrast reviewers have expressed admiration for Beethoven's music. For instance, Alan Blythe, reviewing the 1997 Deutsche Gramophone recording for Gramophone, called it "really worth hearing" (in contradistinction to most of Beethoven's miscellaneous stage music).[29] In 1954, on the first publication of the work by Willy Hess (see below), the musicologist Donald MacArdle rejoiced: "For the concert-goer, Hess has brought back to life a melodious and dramatic composition which should be widely heard and enjoyed"[30] (the intervening decades have not, it seems, brought this wish to fulfillment).

Lockwood writes:

Vestas Feuer shows Beethoven advancing his knowledge of operatic technique for the first time. We see him carefully fashioning an opening scene on the Mozartean model, devoting himself to it with his usual concentration and creative seriousness, determined to give it his best despite the triviality of the text. This score and its sketches (the latter still unpublished) show him working to rescue something of value from Schikaneder's libretto. More than a few moments in the score -- Malo's running feet, the hero and heroine's quiet pledge of love, Sartagones' confrontation with Porus, and finally, the swiftly moving, well-knit Trio -- show the mature Beethoven endeavoring to make something emotionally and musically effective from the materials he had to work with. However modest its place in Beethoven's larger development, Vestas Feuer is valuable for what it reveals: Beethoven, in a crucial year of his artistic life, striving to master operatic technique, poised between one of his greatest models, The Magic Flute, and his own first complete opera to come.[31]

Publication history

Vestas Feuer was forgotten for decades. In 1865, Beethoven's biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer pointed out "that the archives of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde contained a draft, complete in all significant details, of an operatic movement by Beethoven" (quotation from MacArdle 1954). Gustav Nottebohm published extracts of the unidentified material in 1872.[32] In 1930 the work was identified by Raoul Biberhofer as being the opening scene of Vestas Feuer by Schikaneder.[33] Full publication of the work took place only in 1953, under the editorship of the musicologist Willy Hess. A further edition was prepared by Clayton Westermann and published in 1983; it was performed at the Spoleto Festival and in New York at Alice Tully Hall.[34] For publication details of the two editions see References below.

Editors creating an edition of the work must actually complete, to some degree, the task of composition. According to MacArdle, "in the autograph the vocal parts and the string parts were substantially complete; the wind instruments to be used were clearly indicated, but only occasional notes for them were given."

Discography

- (1980) Orchestra of Rundfunk im Amerikanischen Sektor Berlins (RIAS), Mario Venzago.

- (1997) Susan Gritton (soprano), David Kübler (tenor), Robin Leggate (tenor), Gerald Finley (bass), BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrew Davis. Part of the effort by Deutsche Grammophon to issue the composer's complete oeuvre. The catalog number is 4537132.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Translation from Lockwood (2008:82); a more literal translation would be "Vesta's Fire".

- ↑ Lockwood (2008:81)

- 1 2 3 Lockwood (2008:80)

- 1 2 Lockwood (2008:79)

- ↑ Kolb, Fabian (2006) Exponent des Wandels: Joseph Weigl und die Introduktion in seinen italienischen und deutschsprachigen Opern. Münster: LIT Verlag, p. 105 fn.

- ↑ This opinion is given, for instance, by Lockwood (2008:93).

- ↑ See articles on Op. 31, No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3.

- ↑ Source for this paragraph: Lockwood (2008:80). For Beethoven concerts at the Theater an der Wien, see the article on this theater.

- ↑ Lockwood (2008:82)

- ↑ Translation from Westermann's (1983) edition of the work.

- ↑ Lockwood (2008:83)

- ↑ Westermann (1983:2)

- 1 2 Lockwood (2008:84)

- ↑ Date taken from contents page of Complete sonatas and variations for cello and piano: from the Breitkopf & Härtel complete works edition. Courier Corporation, 1990.

- ↑ They narrate, respectively, the killing of the Commendatore, the conclusion of an ill-fated bet, and the Three Ladies' initial encounter with Tamino.

- ↑ Lockwood (2008:80-81); bracketed commentary is from Lockwood.

- ↑ Lockwood (2008:90-91)

- ↑ Lockwood (2008:87)

- ↑ "Beethoven’s Sketches for Vestas Feuer and their Relationship to the ‘Eroica’ Symphony and Leonore," talk given 1 November 2012 at the University of Alabama; abstract posted on line at .

- ↑ Nedbal (2009:279)

- ↑ Nedbal (2009:279 fn.)

- ↑ A partial libretto was printed in 1809; see . Nedbal (2009:419) was able to study Weigl's score by consulting the manuscript, still preserved in the Austrian National Library.

- ↑ These were the Burgtheater and the Kärntnertortheater.

- ↑ Swafford, Jan (2014) Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Excerpts on line at

- ↑ Lockwood, Lewis (2003) Beethoven: The Music and the Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 55.

- ↑ Barry Cooper (2008) Beethoven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. The cited material may be read on line:

- ↑ Robinson, Paul (1996) Ludwig Van Beethoven: Fidelio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Excerpted on line by Google: .

- ↑ Westermann (1983:1)

- ↑ Blythe's review is posted at .

- ↑ McArdle (1954:134)

- ↑ Lockwood 2008:91-93

- ↑ Gustav Nottebohm (1872) Beethoveniana. Leipzig: C. F. Peters. Reprinted 1970: Johnson Reprint Corporation, New York and London.

- ↑ MacArdle (1954:133). See also: Biberhofer, Raoul (1929-1930) Vestas Feuer. Beethovens erster Opernplan. Die Musik 22:409-414. Not seen; cited in Peter Clive (2001) Beethoven and his World, Oxford University Press; on line at .

- ↑ Westermann (1983:2)

- ↑ Link to the DG recording: .

References

- Scholarly work on Vestas Feuer

- Lockwood, Lewis (2008) Vestas Feuer: Beethoven on the path to Leonore. In Robert Curry, David Gable, and Robert Lewis Marshall (eds.) Variations on the Canon: Essays on Music from Bach to Boulez in Honor of Charles Rosen on His Eightieth Birthday. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. The article may be read in full on line at Google Books: .

- MacArdle, Donald W. (1954) Review of Szene aus Vestas Feuer, für Vokalquartett und Orchester, nach der Operndichtung von Emanuel Schikaneder by Ludwig van Beethoven, by Willy Hess. Notes 12:133-134.

- Nedbal, Martin (2009) Morals across the Footlights: Viennese Singspiel, National Identity, and the Aesthetics of Morality, c. 1770-1820. Ph.D. dissertation, Eastman School of Music. Available on line at .

- Editions of the score

- Hess, Willy (1953) Ludwig van Beethoven. Szene aus Vestas Feuer für Vokalquartett und Orchester nach der Operndichtung, von Emanuel Schikaneder. Nach dem Autograph erstveröffentlicht und ergänzt von Willy Hess. ["Ludwig van Beethoven. Scene from Vestas Feuer for vocal quartet and orchestra, after the libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder, first publication based on the autograph score, completed by Willy Hess"]. Wiesbaden : Bruckner-Verlag. Source: .

- Westermann, Clayton (1983) Vestas Feuer = Vesta's fire : scene from the opera / by Ludwig van Beethoven ; text by Emanuel Schikaneder; completed, edited, and translated by Clayton Westermann. New York: G. Schirmer.