Liberal, Missouri

| Liberal, Missouri | |

|---|---|

| City | |

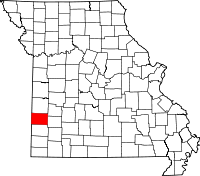

Location of Liberal, Missouri | |

| Coordinates: 37°33′32″N 94°31′14″W / 37.55889°N 94.52056°WCoordinates: 37°33′32″N 94°31′14″W / 37.55889°N 94.52056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Barton |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 0.84 sq mi (2.18 km2) |

| • Land | 0.83 sq mi (2.15 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 902 ft (275 m) |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 759 |

| • Estimate (2012[3]) | 753 |

| • Density | 914.5/sq mi (353.1/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 64762 |

| Area code(s) | 417 |

| FIPS code | 29-41906[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0720953[5] |

Liberal is a city in Barton County, Missouri, United States. The population was 759 at the 2010 census. George Walser founded the city as an atheist utopia in 1880. He named the city after the Liberal League in Lamar, Missouri, to which he belonged. It was to be a city without churches or saloons. Instead it offered experimental programs, such as liberal Sunday morning instruction for children and intellectual lectures for adults on Sunday evenings. Christians arrived as missionaries, first holding religious services in town and later moving to property just outside the city limits.

Geography

Liberal is located at 37°33′32″N 94°31′14″W / 37.55889°N 94.52056°W (37.558860, -94.520546).[6]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 0.84 square miles (2.18 km2), of which, 0.83 square miles (2.15 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[1]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 546 | — | |

| 1900 | 532 | −2.6% | |

| 1910 | 800 | 50.4% | |

| 1920 | 1,160 | 45.0% | |

| 1930 | 848 | −26.9% | |

| 1940 | 771 | −9.1% | |

| 1950 | 739 | −4.2% | |

| 1960 | 612 | −17.2% | |

| 1970 | 644 | 5.2% | |

| 1980 | 701 | 8.9% | |

| 1990 | 684 | −2.4% | |

| 2000 | 779 | 13.9% | |

| 2010 | 759 | −2.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 721 | [7] | −5.0% |

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 759 people, 319 households, and 203 families residing in the city. The population density was 914.5 inhabitants per square mile (353.1/km2). There were 364 housing units at an average density of 438.6 per square mile (169.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.9% White, 0.5% African American, 1.7% Native American, 0.1% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 3.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.8% of the population.

There were 319 households of which 36.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.4% were married couples living together, 12.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.4% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 3.07.

The median age in the city was 34.1 years. 30.3% of residents were under the age of 18; 6.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.9% were from 25 to 44; 21.6% were from 45 to 64; and 14.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.8% male and 52.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 779 people, 328 households, and 212 families residing in the city. The population density was 930.7 people per square mile (358.1/km²). There were 361 housing units at an average density of 431.3 per square mile (165.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 96.02% White, 0.26% African American, 1.54% Native American, 0.13% Asian, and 2.05% from two or more races. 1.16% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 328 households of which 36.6% housed children under the age of 18, 47.3% were married couples living together, 14.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.1% were non-families. 33.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 19.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.98.

In the city the population was spread out with 30.4% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 18.2% from 45 to 64, and 16.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females there were 82.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $24,375, and the median income for a family was $30,625. Males had a median income of $22,656 versus $21,406 for females. The per capita income for the city was $11,246. 19.6% of the population and 14.7% of families were below the poverty line. 30.7% of those under the age of 18 and 14.0% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

History

Founding and founder

Liberal, Missouri, named after the Liberal League in Lamar, Missouri (to which the town's organizer belonged), was started as an atheist, "freethinker" utopia in 1880 by George Walser, an anti-religionist, agnostic lawyer. He bought 2,000 acres (8 km2) of land and advertised across the country for atheists to come and

"found a town without a church, [w]here unbelievers could bring up their children without religious training," and where Christians were not allowed. "His idea was to build up a town that should exclusively be the home of Infidels...a town that should have neither God, Hell, Church, nor Saloon." Some of the early inhabitants of Liberal even encouraged other infidels to move to their town by publishing an advertisement which boasted that Liberal "is the only town of its size in the United States without a priest, preacher, church, saloon, God, Jesus, hell or devil."

From the December 1, 1938 edition of the The Sikeston Herald (Missouri):

The founder of this unique community experiment, George H. Walser, was born in Indiana in 1834. He went to Barton County, Missouri immediately after the war, where he was soon recognized as one of the best lawyers in southwest Missouri. He was elected prosecuting attorney there, and became a member of the 25th assembly. With an eye for future developments he purchased 2,000 acres (8 km2) of land and selected the site of Liberal as the home of an experiment in intellectual community living. He was an agnostic and placed himself in open opposition to organized religion. "With one foot upon the neck of priestcraft and the other upon the rock of truth," he declared, "we have thrown our banner to the breeze and challenge the world to produce a better cause for the devotion of man than that of a grand, noble and perfect humanity."

In harmony with the purpose for organizing the town a number of unusual institutions designed to promote the ideal community were tried during the 1880s and 1890s. The first of these was a Sunday Morning Instruction School, where children were taught from "Youth Liberal Guide" and from various works on physics, chemistry, and other sciences. In another class organized for older young people elementary experiments in the physical sciences were performed under the supervision of teachers whose avowed function was to encourage and direct free intelligent discussion. In the Mental Liberty Hall lectures were given each Sunday evening, and scientists, philosophers, socialists, atheists, Protestant ministers and Catholic priests were invited to speak—respectable decorum being the only limitation placed upon any speaker. Large enthusiastic crowds gathered each week in the interest of mental liberty.

The Liberal Normal School and Business Institute was another institution organized by Walser to promote liberal education free from the bias of Christian theology. This school was well advertised and soon had a large enrollment. According to a tract published in 1885, the Liberal Normal School and Business Institute was "located in the liberal town, taught by liberal teachers and courted only the patronage of liberal patrons." Out of this organization developed Free Thought University, which opened in 1886 with a staff of seven teachers.

Christian missionaries

Christians found Liberal to be a perfect mission field.

As news spread about Liberal, Christians came to convert the town. Walser tried to keep them out by posting his followers at the Liberal train station to tell passengers that if they were Christians they were not welcome, according to an 1896 article in The Kansas City Star. They came anyway. Some Christians quietly bought homes and began holding religious services. Walser would interrupt them and even put a stop to it after he proved to a court that the services were being held on properties he still partly owned. The Christians then bought land next to Liberal and moved more than a dozen houses there from Liberal. The last building had a sign attached that said: "And the Lord said: Get thee out of Sodom." Walser then built a barbed wire fence to keep them out of Liberal. It was time to fulfill the original aim of the town to "enjoy the full benefits of free American citizens without having some self-appointed bigot dictate to us what we should think." (Kansas City Star on Saturday, December 22, 2001)

Regarding the adjoining town that the Christians created:

In an effort to throw off the yoke of Walser, the Christians purchased an eighty-acre tract of land adjoining the town, called the place Pedro and moved their houses and places of business out of Liberal. ( The Sikeston Herald (Missouri), December 1, 1938)

Quality of life

There are a few out-of-print books that discuss the history of the town. They include:

- This strange town—Liberal, Missouri: Founded by G.H. Walser as a place set apart for freethinkers. A history of the early years of the town, 1880–1910, ... Christians, and other human interest stories by JP Moore

- The Story of Liberal Missouri by O.E. Harmon, 1925, a transcription of which is available online.

- George H.Walser and Liberal Missouri by Boyce Mouton who is a pastor.

Liberal's agnostic founder and spiritualism

Later in life, Walser looked into the contemporary issue of spiritualism;

Walser and others became ardent converts of spiritualism, and he spent $40,000 laying out a camp meeting ground of thirteen acres, with twenty cottages, and auditorium seating 800 people, and grounds landscaped with catalpa trees. In addition he built a magnificent home for himself and called it Catalpa Park. On these elaborate camp grounds a number of international conventions of spiritualism were held, attended by as many as 2,000 converts. Walser died in 1910, a firm believer in the spiritualistic. (The Sikeston Herald (Missouri), December 1, 1938)

Walser's later conversion to Christianity

It is not clear if Walser's later Christianity was a hybrid with his earlier spiritualism, but he did author a book entitled The Life and Teachings of Jesus.

When he died in May 1910, the funeral was held at his home and there were remembrances and music. Then there were excerpts read from a book titled The Life and Teachings of Jesus. It was published in 1909, and the author was Walser. He was, he wrote, a converted infidel.

By surviving accounts, he didn't try to push his new beliefs on others. But he did write the book, a remarkable document from someone who once said that Christianity and the Bible were the crude reasoning of primitive man. He had searched for hope during his life through materialism, atheism, agnosticism and spiritualism but had found none.

Walser wrote in the book that he had "wandered in the desert of disbelief, waded in the river of doubt, and in the sands of desolation." But near the end of his life he found hope. Jesus was the son of God, Walser concluded, and the Holy Ghost was the infinite spirit of our maker. "We should study the chart which Jesus has given us," Walser said. (The Kansas City Star on Saturday, December 22, 2001)

References

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

External links

- Barton County Library

- Historic maps of Liberal in the Sanborn Maps of Missouri Collection at the University of Missouri