Kingdom of Tondo

| Kingdom of Tondo | ||||||||||||||||||

| ᜃᜑᜍᜒᜀᜈ᜔ ᜅ᜔ ᜆᜓᜈᜇᜓ Kaharian ng Tondo Kaarian ning Tundo Pagarian ti Tondo Kahadean ini Tundo Kerajaan Tundun | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tondo (Now a modern district of Manila) | |||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Old Tagalog, Kapampangan, Bikol, Ilocano (local languages) Middle Chinese, Old Malay (business languages), Sanskrit and Pali (religious activities) | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism, Buddhism, Folk religion and Islam | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Lakanate | |||||||||||||||||

| Lakan | ||||||||||||||||||

| • | Iron Age – (pre 900 AD) | Amaron | ||||||||||||||||

| • | c. 900 | Jayadewa (First according to LCI) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1200–1245? | Rajah Alon | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1390?–1417? | Rajah Gambang | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1558–1571 | Banaw Lakan Dula | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1575–1587 | Magat Salamat (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age Classical Antiquity High Middle Ages | |||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | c. 900s | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Diplomacy with the Medang | 900 AD | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Fortified mandala | c. 1150 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Rajah Alon expanded the territories | 1200 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Majapahit–Luzon war | 1365 | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Diplomacy with Ming Dynasty – 1378 Annexed by Bruneian Empire – 1500 |

|||||||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1589 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Piloncitos, Gold rings and Barter | |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Brunei | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

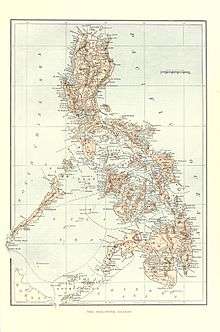

The Kingdom of Tondo (Filipino: Kaharian ng Tondo; Baybayin: Pre-Kudlit:ᜎᜓᜐᜓ (Lusu), Post-Kudlit: ᜃᜑᜍᜒᜀᜈ᜔ ᜅ᜔ ᜆᜓᜈᜇᜓ ; Kapampangan: Kaarian ning Tundo; Bikol: Kahadean ini Tundo; Ilocano: Pagarian ti Tondo; Chinese: 東都; pinyin: dōngdū; Malay: Kerajaan Tundun), also referred to as Tundo, Tundun, Tundok, Tung-lio, Lusung, or Ancient Tondo, was a mandala which was located in the Manila Bay area, specifically north of the Pasig River, on Luzon island.[3](p71)[4] It is one of the settlements mentioned by the Philippines' earliest historical record, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (900 CE). Its territories stretched from the mouth of the Pasig river to the Kapampangan chiefdoms[1] up to the Southern Luzon southwards to Bicolandia,[1] making it the largest [1] kingdom that covered the most of Luzon.[1]

Originally an Indianized kingdom in the 10th century, Tondo built upon and capitalized on being central to the long-existing ancient regional trading routes throughout the archipelago to include among others, initiating diplomatic and commercial ties with China during the Ming Dynasty. Thus it became an established force in trade throughout Southeast Asia and East Asia. (See Luções). Tondo's regional prominence further culminated during the period of its associated trade and alliance with Brunei's Sultan Bolkiah, when around 1500 its peak age as a thalassocratic force in the northern archipelago was realized. When the Spanish first arrived in Tondo in 1570 and defeated the local rulers in the Manila Bay area in 1591, Tondo came under the administration of Manila (a Spanish fort built on the remains of Kota Seludong), ending its existence as an independent polity. This subjugated Tondo continues to exist today as a district of the city of Manila.

Etymology

Numerous theories on the origin of the name "Tondo" have been put forward. Filipino National Artist Nick Joaquin suggested that it might be a reference to high ground ("tundok").[5] French linguist Jean-Paul Potet, however, has suggested that the River Mangrove, Aegiceras corniculatum, which at the time was called "tundok" ("tinduk-tindukan" today), is the most likely origin of the name.[6]

The bay area in which Tondo can be found was named Lusong or Lusung, a name thought to have been derived from the Tagalog word for a large wooden mortar used in dehusking rice.[7][8] This name was eventually used as the modern name of the entire island of Luzon.[9]

Records

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription

The first reference to Tondo occurs in the Philippines' oldest historical record — the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI). This legal document was written in Kawi, and dates back to Saka 822 (c. 900).

The first part of the document says that:

On this occasion, Lady Angkatan, and her brother whose name is Bukah, the children of the Honourable Namwaran, were awarded a document of complete pardon from the King of Tundun, represented by the Lord Minister of Pailah, Jayadewa.

Apparently, the document was a sort of receipt that acknowledged that the man named Namwaran had been cleared of his debt to the King of Tundun, which in today's measure would be about 926.4 grams of gold.[10]

The article mentioned that other places in the Philippines and their Rulers: Pailah (Lord Minister Jayadewa), Puliran Kasumuran (Lord Minister), Binwangan (unnamed). It has been suggested that Pailah, Puliran Kasumuran, and Binwangan are the towns of Paila, Pulilan, and Binwangan in Bulacan, but it has also been suggested that Pailah refers to the town of Pila, Laguna. More recent linguistic research of the Old Malay grammar of the document suggests the term Puliran Kasumuran refers to the large lake now known as Laguna de Ba'y (Puliran), citing the root of kasumuran, *sumur as Old Malay for well, spring or freshwater source. Hence ka-sumur-an defines a water-source (in this case the freshwater lake of Puliran itself).[11] While the document does not describe the exact relationship of the King of Tundun with these other rulers, it at least suggests that he was of higher rank.[12]

Expansionism

Rajah Alon (c.1200), King of Tondo and son of Lakan Timamanukum, expanded the Kingdom of Tondo by conquering neighboring territories such as Kapampangan chiefoms, Kumintang (Batangas) and Bicol. He was succeeded by his grandson Rajah Gambang. The Tondo Dynasty lasted until the end of the 15th century, when the Sultanate of Brunei conquered it so as to strengthen Brunei's Chinese trade links.[13]

Notable names of places changed through Tondo's history

Inside Modern day NCR

- Bitukang Manók - A realm founded by Dayang Kalangitan, Now called Santa Cruz, Manila.

- Sapa - now Santa Ana, Manila (Also the capital of the Namayan territory).

- Marikina

- Nabotas[14]

- Pandakan[15]

- Pasay[16]

- Tagig - Where BCG stand's today.[17]

Outside Modern NCR

- Kandaba , Pampanga[18]

- Pandakan[19]

- Paila (Pailah) - Now Pila, Laguna (Mentioned in LCI)[20]

- Binuangan (Binwangan) - Now part of Obando, Bulacan and San Lorenzo, Norzagaray, Bulacan. (Mentioned in LCI)

- Puliran - Now Pulilan, Bulacan (Mentioned in LCI)[20]

- The Kumintang Ilaya - Now or part the Batangas Province.[1]

- Tangway - Now called the province of Cavite.[1]

- Morong - Now Rizal Province.[2]

- Tayabas - Now Quezon Province.[2]

- Ibalon - What is now the Bicol region.[1]

- Rawis - An ancient settlement Somewhere in the area of Mt.Mayon, Albay in Bicol region (mentioned in the tale of Daragang Magayon) The area are now part of Legazpi, Albay.[1]

Uncertain places

- Misil- somewhere outside NCR

- Pagalangan - Somewhere in the modern Pila, Laguna[21]

- Polo - somewhere outside NCR

- Katanghalan- somewhere in manila?

Culture and Society

It is believed that the people of Tondo kingdom were related to Malay of Malay peninsula and Sumatra.[3](p71) Since at least the 3rd century, The people of Tondo had developed a culture which is predominantly Hindu and Buddhist Society, They are ruled by a Lakan which is belong to a Caste of Maharlika were the feudal warrior class in ancient Tagalog society in Luzon the Philippines translated in Spanish as Hidalgos, and meaning freeman, libres or freedman.[22] They belonged to the lower nobility class similar to the Timawa of the Visayan people.In modern Filipino, however, the term itself has erroneously come to mean "royal nobility", which was actually restricted to the hereditary Maginoo class.[23]

| Kingdom of Tondo | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 東都 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kyūjitai | 呂宋. | ||||||

| |||||||

Social Structure

The different type of culture prevalent in Luzon gave a less stable and more complex social structure to the pre-colonial Tagalog barangays of Manila, Pampanga and Laguna. Enjoying a more extensive commerce than those in Visayas, having the influence of Bornean political contacts, and engaging in farming wet rice for a living, the Tagalogs were described by the Spanish Augustinian friar Martin de Rada as more traders than warriors.[24]

The more complex social structure of the Tagalogs was less stable during the arrival of the Spaniards because it was still in a process of differentiating. A Jesuit priest Francisco Colin made an attempt to give an approximate comparison of it with the Visayan social structure in the middle of the 17th century. The term datu or lakan, or apo refers to the chief, but the noble class to which the datu belonged to was known as the maginoo class. Any male member of the maginoo class can become a datu by personal achievement.[25]

The term timawa referring to freemen came into use in the social structure of the Tagalogs within just twenty years after the coming of the Spaniards. The term, however, was being incorrectly applied to former alipin (commoner and slave class) who have escaped bondage by payment, favor, or flight. Moreover, the Tagalog timawa did not have the military prominence of the Visayan timawa. The equivalent warrior class in the Tagalog society was present only in Laguna, and they were known as the maharlika class.

At the bottom of the social hierarchy are the members of the alipin class. There are two main subclasses of the alipin class . The aliping namamahay who owned their own houses and served their masters by paying tribute or working on their fields were the commoners and serfs, while the aliping sa gigilid who lived in their masters' houses were the servants and slaves.

Pottery

Tondo had a rich tradition of pottery Japanese texts mentioned trading expeditions to the island of Rusun (Luzon) for the highly prized Rusun and Namban jars occurred. Japanese texts were very specific about these jars being made in Luzon 呂宋. The Tokiko, for example, calls the Rusun and Namban jars, Ru-sun tsukuru or Lu-sung ch'i (in Chinese), which means simply "made in Luzon."[26] These Rusun jars, which had rokuru (wheel mark), were said to be more precious than gold because of its ability to act as tea canisters and enhance the fermentation process.

clay jars used for storing green tea and rice wine with Japan flourished in the 12th century, and local Tagalog, Kapampangan and Pangasinense potters had marked each jar with Baybayin letters denoting the particular urn used and the kiln the jars were manufactured in. Certain kilns were renowned over others and prices depended on the reputation of the kiln.[27] Of this flourishing trade, the Burnay jars of Ilocos are the only large clay jar manufactured in Luzon today with origins from this time.

Economic activities

The people of Tondo were good agriculturists, they lived through farming, rice planting and aquaculture, (specially in lowland areas). A report during the time of Miguel López de Legazpi noted of the great abundance of rice, fowls, wine as well as great numbers of carabaos, deer, wild boar and goat husbandry in Luzon. In addition, there were also great quantities of cotton and colored clothes, wax, wine, honey and date palms produced by the native peoples, rice, cotton, swine, fowls, wax and honey abound.

The use of rice paddies in Pila can be traced to prehistoric times, as evidenced in the names of towns such as Pila, Laguna, whose name can be traced to the straight mounds of dirt that form the boundaries of the rice paddy, or "Pilapil."[28]

Duck culture was also practiced by the natives, particularly those around Pateros and where Taguig City stands today. This resembled the Chinese methods of artificial incubation of eggs and the knowledge of every phase of a duck's life. This tradition is carried on until modern times of making balut.[26]

Trade to "Silk road"

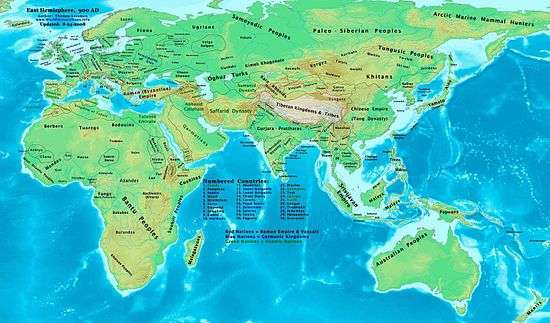

Many of the barangay municipalities were, to a varying extent, under the de jure jurisprudence of one of several neighboring empires, among them the Malay Srivijaya, Javanese Majapahit, Po-ni, Malacca, Indian Chola , Champa , Burma and Khmer empires.

Trading links with Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Malay Peninsula, Indochina, China, Japan, India and Arabia. A thalassocracy had thus emerged based on international trade.

Majapahit suzerainty

In mid 14th century, the Majapahit empire mentioned in its manuscript Nagarakretagama, written by Prapanca in 1365—that the area of Selurong (Majapahit term for Luzon or Maynila) and Solot (Sulu) were parts of the empire.[29][30] The true nature of this Majapahit influence is still a subject of study. As the geographical, logistical and political constraint of the era suggests, that instead of conventional colonization, Majapahit may only exercised minimal ceremonial suzerainty and only claimed trade monopoly of its tributaries. It is likely that Majapahit fleet seldom sailed to its peripheral realm as far north as Luzon. Most often Majapahit left polities of its farthest realm intact, without any further administrative integration.

The fact whether Tondo was a tributary state of Majapahit or not, is still a subject of debate. Those who doubted the validity of Nagarakretagama, pointed out that the manuscript was composed as a eulogy for their emperor Hayam Wuruk, thus not accountable as historical source.[31] Whether an actual battle between Tondo and Majapahit forces ever took place—or just a speculation, is still a subject of debate, due to scarcity of historical records and evidences. Nevertheless, the report of clash between naval forces of Sulu and Majapahit was recorded, when the pirates hailed from Sulu attacked Barune (Brunei) which was a Majapahit vassal, and subsequently repelled by Majapahit forces. Chinese source mentioned that in 1369, the pirates of Sulus attacked Po-ni (Brunei), looting it of treasure and gold. A fleet from Majapahit succeeded in driving away the Sulus, but Po-ni was left weaker after the attack.[32]

Lusung Warriors

Portuguese accounts

Pires noted that they (The Lucoes or people from Luzon) were "mostly heathen" and were not much esteemed in Malacca at the time he was there, although he also noted that they were strong, industrious, given to useful pursuits. Pires' exploration led him to discover that in their own country, the Luções had "foodstuffs, wax, honey, inferior grade gold," had no king, and were governed instead by a group of elders. They traded with tribes from Borneo and Indonesia and Philippine historians note that the language of the Luções was one of the 80 different languages spoken in Malacca[33] When Magellan's ship arrived in the Philippines and East Timor, Pigafetta noted that there were Luções there collecting sandalwood.[34]

The Luções' activities weren't limited to trade however. They also had a reputation for being fierce warriors.

When the Portuguese arrived in Southeast Asia in 1500 AD, they witnessed the Lucoes or the Lusung's active involvement in the political and economic affairs of those who sought to take control of the economically strategic highway of the Strait of Malacca. For instance, the former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 AD.[35]

Pinto noted that there were a number of them in the Islamic fleets that went to battle with the Portuguese in the Philippines during the 16th century. The Sultan of Aceh gave one of them (Sapetu Diraja) the task of holding Aru (northeast Sumatra) in 1540. Pinto also says one was named leader of the Malays remaining in the Moluccas Islands after the Portuguese conquest in 1511.[36] Pigafetta notes that one of them was in command of the Brunei fleet in 1521.[34]

However, the Luções did not only fight on the side of the Muslims. Pinto says they were also apparently among the natives of the Philippines who fought the Muslims in 1538.[36]

On Mainland Southeast Asia, Lusung/Lucoes warriors aided the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Lusung warriors fought alongside the Siamese king and faced the same elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya.[37]

|

|

| A Warrior equipped with Sibat and Kalasag (Sheild) | A Warrior equipped with Arquebuse. |

Diplomatic relations

Relations with the Medang Kingdom (900)

| Pre-hispanic History of the Philippines |

|

|---|

| Barangay government |

| Ten datus of Borneo |

| States in Luzon |

| Luyag na Kaboloan (Pangasinan) |

| Ma-i |

| Kingdom of Maynila |

| Namayan |

| Kingdom of Tondo |

| States in the Visayas |

| Kedatuan of Madja-as |

| Rajahnate of Cebu |

| States in Mindanao |

| Rajahnate of Butuan |

| Sultanate of Sulu |

| Sultanate of Maguindanao |

| Sultanate of Lanao |

| Key figures |

| Sulaiman II · Lakan Dula · Sulaiman III · Katuna |

| Tarik Sulayman · Tupas · Kabungsuwan · Kudarat |

| Humabon · Lapu-Lapu · Alimuddin I |

| History of the Philippines |

| Portal: Philippines |

The Dutch anthropologist and Hanunó'o script expert Antoon Postma has concluded that the Laguna Copperplate Inscription also mentions the places of Tondo (Tundun); Paila (Pailah), now an enclave of Barangay San Lorenzo, Norzagaray; Binuangan (Binwangan), now part of Obando; and Pulilan (Puliran); and Mdaŋ (the Javanese Kingdom of Medang), in present-day Indonesia.[38] Apparently, the Philippine Kingdom of Tondo and the Medang Kingdom of Indonesia were known allies and trading partners.

Diplomacy with the Ming dynasty (1373)

The next historical reference to Ancient Tondo can be found in the Ming Shilu Annals (明实录]),[39] which record the arrival of an envoy from Luzon to the Ming Dynasty (大明朝) in 1373.[39] Her rulers, based in their capital, Tondo (Chinese: 東都; pinyin: dōngdū) were acknowledged not as mere chieftains, but as kings (王).[40] This reference places Tondo into the larger context of Chinese trade with the aboriginals of the Philippine archipelago.

Theories such as Wilhelm Solheim's Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network (NMTCN) suggest that cultural links between what are now China and the nations of Southeast Asia, including what is now the Philippines, date back to the peopling of these lands.[41] But the earliest archeological evidence of trade between the Philippine aborigines and China takes the form of pottery and porcelain pieces dated to the Tang and Song Dynasties.[42]

The rise of the Ming dynasty saw the arrival of the first Chinese settlers in the archipelago. They were well received and lived together in harmony with the existing local population — eventually intermarrying with them so that today, numerous Filipinos have Chinese blood in their veins.[42]

This connection was important enough that when the Ming Dynasty emperors enforced the Hai jin laws which closed China to maritime trade from 1371 to about 1567, trade with the Kingdom of Tondo was officially allowed to continue, masqueraded as a tribute system, through the seaport at Fuzhou.[43] Aside from this, a more extensive clandestine trade from Guangzhou and Quanzhou also brought in Chinese goods to Luzon.[44]

Luzon and Tondo thus became a center from which Chinese goods were traded all across Southeast Asia. Chinese trade was so strict that Luzon traders carrying these goods were considered "Chinese" by the people they encountered.[44]

This powerful presence in the trade of Chinese goods in 16th-century East Asia was also felt strongly by Japan. The Ming Empire treated Luzon traders more favorably than Japan by allowing them to trade with China once every two years.

Diplomacy with Japan

Japan was only allowed to trade once every 10 years. Japanese merchants often had to resort to piracy in order to obtain much sought after Chinese products such as silk and porcelain. Famous 16th-century Japanese merchants and tea connoisseurs like Shimai Soushitsu (島井宗室) and Kamiya Soutan (神屋宗湛) established branch offices on the island of Luzon. One famous Japanese merchant, Luzon Sukezaemon (呂宋助左衛門), went as far as to change his surname from Naya (納屋) to Luzon (呂宋).

Attack by the Bruneian Empire (1500)

Around the year 1500, the Sultanate of Brunei under Sultan Bolkiah attacked the kingdom of Tondo and established a city with the Malay name of Selurong (later to become the city of Maynila)[45][46] on the opposite bank of Pasig River. The traditional Rajahs of Tondo, the Lakandula, retained their titles and property but the real political power came to reside in the House of Soliman, the Rajahs of Manila.[47]

Islamization by forced conversion of the citizens of Tondo and Manila divided the area into Muslim domains. The Bruneians installed the Muslim rajahs, Rajah Suleyman and Rajah Matanda in the south (now the Intramuros district) and the Buddhist-Hindu settlement under Raja Lakandula in northern Tundun (now Tondo.)[48] With the rise of Islam, other religions in the archipelago gradually disappeared.

Incorporation into the Sultanate of Brunei (1500)

Tondo became so prosperous that around the year 1500, the Sultanate of Brunei under Sultan Bolkiah merged it by a royal marriage of Gat Lontok, who later became Rajah of Namayan, and Dayang Kaylangitan to establish a city with the Malay name of Selurong (later to become the city of Maynila)[49][50]

on the opposite bank of Pasig River. The traditional rulers of Tondo, the Lakandula, retained their titles and property upon embracing Islam but the real political power transferred to the master trader House of Sulayman, the Rajahs of Manila.[51]

Spanish contact and decline (1570–1591)

Spanish colonizers from Mexico first came to the Manila Bay area and its settlements in June 1570, while Miguel López de Legazpi was searching for a suitable place to establish a capital for the new territory. Having heard from the natives of a prosperous Moro settlement on the island of Luzon, López de Legazpi had sent Martín de Goiti to investigate. When Maynila's ruler, Rajah Sulaiman II, refused to submit to Spanish sovereignty, de Goiti attacked. He eventually defeated Rajah Sulaiman, claimed Maynila in the name of the King of Spain, then returned to report his success to López de Legazpi, who was then based on the island of Panay.

López de Legazpi himself returned to take the settlement on 19 June 1571. When the Spanish forces approached, the natives burned Maynila down and fled to Tondo and other neighboring towns.

López de Legazpi began constructing a fort on the ashes of Maynila and made overtures of friendship to Lakandula of Tondo, who accepted. The defeated Sulaiman refused to submit to the Spaniards, but failed to get the support of Lakandula or of the Kapampangan and Pangasinan settlements to the north. When Sulaiman and a force of Muslim warriors attacked the Spaniards in the battle of Bangcusay, he was finally defeated and killed.

This defeat marked the end of rebellion against the Spanish among the Pasig river settlements, and Lakandula's Tondo surrendered its sovereignty, submitting to the authority of the new Spanish capital, Manila.[52]

Battle of Bankusay Channel

In the on June 3, 1571 marked the last resistance by locals to the occupation and colonization by the Spanish Empire of Manila in the The Battle of Bankusay Channel on June 3, 1571 marked the last resistance by locals to the occupation and colonization by the Spanish Empire of Manila, the Philippines. Tarik Sulayman, the chief of Macabebes, refused to ally with the Spanish and decided to mount an attack at Bankusay Channel on Spanish forces, led by Miguel López de Legazpi. Sulayman's forces were defeated, and he was killed. The Spanish victory in Bankusay and Legaspi's alliance with Lakandula of Kingdom of Tondo, enabled the Spaniards to establish themselves throughout the city and its neighboring towns. the Philippines. Tarik Sulayman, the leader of the Macabebes, refused to ally with the Spanish and decided to mount an attack at Bankusay Channel on Spanish forces, led by Miguel López de Legazpi. Sulayman's forces were defeated, and he was killed. The Spanish victory in Bankusay and Legaspi's alliance with Lakandula of the Kingdom of Tondo, enabled the Spaniards to establish themselves throughout the city and its neighboring towns.

Tondo Conspiracy

The Conspiracy of the Maharlikas, also referred to as the Revolt of the Lakans from 1587–1588 was a plot against Spanish colonial rule by the Tagalog and Kapampangan noblemen, or Datus, of Manila and some towns of Bulacan and Pampanga, in the Philippines. They were the indigenous rulers of their area or an area yet upon submission to the might of the Spanish was relegated as mere collector of tributes or at best Encomenderos that need to report to a Spanish Governor. It was led by Agustín de Legazpi, the son of a Maginoo of Tondo (one of the chieftains of Tondo), born of a Spanish mother given a Hispanized name to appease the colonizers, grandson of conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi, nephew of Lakan Dula, and his first cousin, Martin Pangan. The datus swore to rise up in arms. The uprising failed when they were betrayed to the Spanish authorities by Antonio Surabao (Susabau) of Calamianes.[53]

Historical theories associated with Ancient Tondo

Lakan as a title

While most historians think of Lakan Dula as a specific person, with Lakan meaning Lord, King or Paramount Ruler and Dula being a proper name, one theory suggests that Lakandula is a hereditary title for the Monarchs of the Kingdom of Tondo.[54]

The heirs of Lakan Banao Dula

In 1587, Magat Salamat, one of the children of Lakan Dula, and with his Spanish enforced name Augustin de Legazpi, Lakan Dula's nephew, and the lords of the neighboring areas of Tondo, Pandakan, Marikina, Kandaba, Nabotas and Bulakan were martryed for secretly conspiring to overthrow the Spanish colonizers. Stories were told that Magat Salamat's descendants settled in Hagonoy, Bulacan and many of his descendants spread from this area.[55]

David Dula y Goiti, a grandson of Lakan Dula with a Spanish mother escaped the persecution of the descendants of Lakan Dula by settling in Isla de Batag, Northern Samar and settled in the place now called Candawid (Kan David). Due to hatred for the Spaniards, he dropped the Goiti in his surname and adopted a new name David Dulay. He was eventually caught by the Guardia Civil based in Palapag and was executed together with seven followers. They were charged with planning to attack the Spanish detachment.[55]

Notable monarchs of Tondo

Legendary Rulers

- Legendary rulers can be found in the oral tradition in Philippine Mythology, which having a uncertain historical /archeological evidence of their reign.

| Image | Name | Title held/Notes | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ama-ron or Amaron | Amaron is like most of the male Filipino mythological heroes, he is described as an attractive well-built man who exemplifies great strength. Ama-ron is unique among other Filipino legends due to the lack of having a story on how he was born which was common with Filipino epic heroes. | Uncertain possibly Iron Age.[56] | ||

| Gat Pangil | Gat Pangil was a chieftain in the area now known as Laguna Province, He is mentioned in the origin legends of Bay, Laguna,Pangil, Laguna, Pakil, Laguna and Mauban, Quezon, all of which are thought to have once been under his domain. | Uncertain possibly Iron Age.[2] |

Historical Rulers of Tondo

| Image | Name | Title held/Notes | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jayadeva Jayadewa | Senapati (Admiral) (Known only in the LCI as the King who gave the pardon to Lord Namwaran and his wife Dayang Agkatan and their daughter named Bukah for their excessive debts in 900 AD.) [10] | 900? | ? | |

| Lakan Timamanukum | Father of Rajah Alon, he ruled when Tondo become a fortified Mandala at the mouth of Pasig River. | 1150? | ? | |

| Alon | Lakan Alon (Son of Lakan Timamanukum, he expanded the Tondo territory from Ilocandia to Bicolandia.) | 1200? | ? | |

| Gambang | Lakan Gambang another ruler who used the title Senapati or Admiral. | 1390? | 1417? | |

| Suko | Lakan Suko (or also known as Sukwu (朔霧) means "northern mist" , According to the Dongxi Yanggao (東西洋考) Abdicated .) | 1417? | 1430? | |

| Lontok | Lakan Lontok (later converted his faith to Islam.) | 1430? | 1450? | |

| Kalangitan | Dayang Kaylangitan, Queen of Namayan and Tondo. (the only recorded queen regnant of the pre-Hispanic Philippine Kingdom of Tondo. The eldest daughter of Rajah Gambang and co-regent with her husband, Rajah Lontok, she is considered one of the most powerful rulers in the kingdom's history.) | 1450? | 1515? | |

| Salalila | Rajah Salalila or Rajah Sulayman I (A puppet Rajah installed by Sultan Bolkiah .) | 1515? | 1558? | |

| Matanda | Rajah Matanda or Rajah Sulayman II or Rajah Ache, King of Namayan | 1558? | 1571 | |

| Lakan Dula | Banaw Lakandula, King of Tondo and Sabag | 1558? | 1571 | |

| Sulayman | Rajah Sulayman, King of Tondo | 1571 | 1585 | |

| Magat Salamat | The last ruler of Tondo dynasty after the monarchy was dissolved by the Spanish authorities due to the fact that he lead the Tondo conspiracy. | 1575 | 1587 |

Connection to Mayi

There was nearby state, Ma-i or Mayi, whose ruler used 30 people as human sacrifices in his funeral, the subordinates of Mayi were Baipuyan (Babuyan Islands), Bajinong (Busuanga), Liyin (Lingayen) and Lihan (present day Malolos City). Malolos is a coastal town and one of the ancient settlement around Manila Bay near Tondo.[57][58]

See also

Additional reading

- Joaquin, Nick (1988). Culture and History. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, Inc. p. 411. ISBN 971-27-1300-8.

- Jocano, F. Landa (2001). Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage. Quezon City: Punlad Research House, Inc. ISBN 971-622-006-5.

- Scott, William Henry (1992). Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0524-7.

- Ongpin Valdes, Cynthia, "Pila in Ancient Times", Treasures of Pila, Pila Historical Society Foundation Inc.

- Santiago, Luciano, "Pila: The Noble Town", Treasures of Pila, Pila Historical Society Foundation Inc.

Bolkiah Era

- "National Day of Brunei Darussalam (Editorial)", Manila Bulletin, February 23, 2006 Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - Laput, Ernesto. "The first invader was a neighbor: Ang Unang Conquistador". Pinas: Munting Kasaysayan ng Pira-pirasong Bayan. elaput.com. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

Spanish Era

- Alabastro, Tony (April 29, 2002). "Soul of the Walled City (Brief History of Intramuros)". Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- Flores, Wilson Lee (February 22, 2005), "Proud to be a Tondo Boy", The Philippine Star

- Joaquin, Nick (1983). The Aquinos of Tarlac: An Essay on History as Three Generations. Manila, Philippines: Solar Publishing Corporation.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/philippines/history-tondo.htm

- 1 2 3 4 http://elgu2.ncc.gov.ph/mauban/index.php?id1=3&id2=1&id3=0

- 1 2 Schliesinger, Joachim (2016). Origin of Man in Southeast Asia 4: Early Dominant Peoples of the Maritime Region. Volume 4 dari Origin of Man in Southeast Asia. Booksmango. ISBN 9781633237285.

- ↑ Abinales, Patricio N. and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005. as referred to in http://malacanang.gov.ph/75832-pre-colonial-manila/#_ftn1

- ↑ Joaqiun, Nick (1990). Manila, My Manila: A History for the Young. City of Manila: Anvil Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-9715693134.

- ↑ Potet, Jean-Paul G. (2013). Arabic and Persian Loanwords in Tagalog. p. 444. ISBN 9781291457261.

- ↑ Keat Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. p. 798. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- ↑ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 59.

- ↑ Zaide, Sonia M. The Philippines, a Unique Nation. p. 50.

- 1 2 Morrow, Paul (2006-07-14). "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription". Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Tiongson, Jaime (2006-11-29). "Pailah is Pila, Laguna". Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Santos, Hector (1996-10-26). "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription". Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Pike, John. "Tondo (Tongdo, Tongdo, Ytondo, Tundun, Tung-lio)". Globalsecurity.org.

- ↑ Fernando A. Santiago Jr., Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898, retrieved 2008-07-18

- ↑ Fernando A. Santiago Jr., Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898, retrieved 2008-07-18

- ↑ "About Pasay – History: Kingdom of Namayan". pasay city government website. City Government of Pasay. Archived from the original on 2008-01-20. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Fernando A. Santiago Jr., Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898, retrieved 2008-07-18

- ↑ Fernando A. Santiago Jr., Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898, retrieved 2008-07-18

- ↑ Fernando A. Santiago Jr., Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898, retrieved 2008-07-18

- 1 2 Tiongson, Jaime F. (2010-08-08). "Laguna Copperplate Inscription: A New Interpretation Using Early Tagalog Dictionaries". Bayang Pinagpala. Retrieved on 2011-11-18.

- ↑ "History of Pila - A Glorious Past". Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ↑ Scott, William Henry (1992). Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino and Other Essays in the Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0524-7.

- ↑ Paul Morrow (January 16, 2009). "Maharlika and the ancient class system". Pilipino Express. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 124-125.

- ↑ Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 125.

- 1 2 Ancient Philippine Civilization. Accessed January 7, 2013.(archived from the original on 2007-12-01

- ↑ Kekai, Paul. (2006-09-05) Quests of the Dragon and Bird Clan: Luzon Jars (Glossary). Sambali.blogspot.com. Retrieved on 2010-12-19.

- ↑ Ongpin Valdes, Cynthia, "Pila in Ancient Times", Treasures of Pila, Pila Historical Society Foundation Inc

- ↑ "A Complete Transcription of Majapahit Royal Manuscript of Nagarakertagama". Jejak Nusantara (in Indonesian)).

- ↑ Malkiel-Jirmounsky, Myron (1939). "The Study of The Artistic Antiquities of Dutch India". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 4 (1): 59–68. doi:10.2307/2717905. JSTOR 2717905.

- ↑ Day, Tony & Reynolds, Craig J. (2000). "Cosmologies, Truth Regimes, and the State in Southeast Asia". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 34 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003589. JSTOR 313111.

- ↑ History for Brunei 2009, p. 44

- ↑ Chinese Muslims in Malaysia, History and Development by Rosey Wang Ma

- 1 2 Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. "First voyage round the world". Translated by J.A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

- ↑ Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.

- 1 2 Pinto, Fernao Mendes (1989) [1578]. "The travels of Mendes Pinto.". Translated by Rebecca Catz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Ibidem, page 195.

- ↑ Antoon, Postma. "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Loyola Heights, Quezon City, the Philippines: Philippine Studies, Ateneo de Manila University. p. 200. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- 1 2 Ming Annals (Chinese (archived from the original on 2008-04-11)

- ↑ Volume 5 of 東西洋考 (A study of the Eastern and Western Oceans) mentions that Luzon first sent tribute to Yongle Emperor in 1406.

- ↑ Solheim, Wilhelm G., II (2006). Archaeology and Culture in Southeast Asia: Unraveling the Nusantao. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. p. 316. ISBN 971-542-508-9.

- 1 2 "Embassy Updates: China-Philippine Friendly Relationship Will Last Forever" (Press release). Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Republic of the Philippines. October 15, 2003. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 0-521-66991-X.

- 1 2 San Agustin, Gaspar de. Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas 1565–1615 (in Spanish and English). Translated by Luis Antonio Mañeru (1st bilingual ed [Spanish and English] ed.). Intramuros, Manila, 1998: Pedro Galende, OSA.

- ↑

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ↑ del Mundo, Clodualdo (September 20, 1999). "Ako'y Si Ragam (I am Ragam)". Diwang Kayumanggi. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ↑ Santiago, Luciano P.R., The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda, and Soliman [1571-1898]: Genealogy and Group Identity, Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 18 [1990]

- ↑ Teodoro Agoncillo, History of the Filipino People, p 22

- ↑

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ↑ del Mundo, Clodualdo (September 20, 1999). "Ako'y Si Ragam (I am Ragam)". Diwang Kayumanggi. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ↑ Santiago, Luciano P.R., The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda, and Sulayman [1571–1898]: Genealogy and Group Identity, Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 18 [1990]

- ↑ Gardner, Robert (1995-04-20). "Manila – A History". Philippine Journeys. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Tomas L., Magat Salamat, Archived from the original on October 27, 2009, retrieved 2008-07-14

- ↑ Santiago, Luciano P.R., The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda, and Soliman [1571–1898]:Genealogy and Group Identity, Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 18 [1990].

- 1 2 "lakandula". Archived from the original on 2008-02-24. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ http://www.ualberta.ca/~vmitchel/rev2.html

- ↑ Wang Zhenping (2008). "Reading Song-Ming Records on the Pre-colonial History of the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of East Asian Cultural Interaction Studies. 1: 249–260. ISSN 1882-7756.

- ↑ Informe sobre el estado de las Islas Filipinas en 1842, Tomo 1, Madrid 1843, p. 139

Coordinates: 14°37′38″N 120°58′17″E / 14.62722°N 120.97139°E