Religion in Taiwan

Religion in Taiwan (2005 census)[1]

Religion in Taiwan is characterized by a diversity of religious beliefs and practices, predominantly those pertaining to Chinese culture and Chinese traditional religions. Freedom of religion is inscribed in the constitution of the Republic of China. According to the census of 2005, 35% of the population is composed of Buddhists, 33% of Taoists (including local religion), 3.9% of Christians, 18.7% of people who identify as not religious, and approximately 10% of adherents to religious movements of Taoist or Confucian origin (among them 3.5% adhere to Yiguandao).

Surveys try to distinguish between Buddhism and Taoism in Taiwan, which, along with Confucianism, come under the general category "religion in China". However, a strict distinction is dubious because Taoist deities are worshiped along with Buddhist deities such as Goddess of Mercy in temples across the country.

History

Prior to the 17th century the island of Taiwan was inhabited by the Taiwanese aborigines of Austronesian stock, and there were small settlements of Chinese and Japanese maritime traders and pirates.[2] Taiwanese aborigines traditionally practiced an animistic ethnic religion. With the introduction of Dutch rule in 1624, Protestantism was spread to the Taiwanese aborigines. Two years later, with the transition to the Spanish rule, the Catholic Church was introduced to the island.

When the Han Chinese began to settle the island and form the Taiwanese Chinese ethnic group, exchanges between the indigenous religion of the Austronesian aborigines and the Chinese folk religion occurred.[3] For instance, Ali-zu, the Siraya god of fertility, has been incorporated into the Han pantheon in some places of Taiwan.[4]

17th and 18th centuries

A large influx of Han Chinese began in the 1660s with the transition of imperial power from the Ming dynasty to the Manchurian Qing dynasty.[5] Many Ming loyalists fled to the south, including Zheng Chenggong alias Koxinga, a military leader who fought against the Manchu dynasty.[5] He sailed into Taiwan in 1661 with thousands troops, and in a brief military endeavour he drove out the Dutch and established the Kingdom of Tungning, the first Chinese state on the island.[5] Chinese settlers mostly from Fujian and Guangdong began to migrate to the island.[5] The policy of migration to Taiwan was restrictive until 1788, even after the island came under political control of the Qing in 1683.[5]

Chinese migrants brought with them local cults from the mainland, which served to integrate communities around the worship of locality and community gods.[5] As the settlers were mostly males, came from different areas, and at first there weren't many people sharing the same surnames and belonging to the same kins, ancestral shrines of kinship gods didn't develop until 1790s when sufficient generations of families had established on the island.[6]

The first settlers in Koxinga and Qing periods brought with them images or incense ashes from mainland temples, installed them in homes or temporary thatched huts, and later in proper temples, as economic circumstances permitted to build them.[7] Prominent temples became the foci of religious, political and social life, often eclipsing Qing officials and state-sponsored temples in their influence.[7]

There is little evidence that the doctrinal and initiatory religions of Buddhism and Taoism were active during this period.[7] Taiwan, as a frontier land, was not attractive for Buddhist and Taoist religious leaders.[7]

19th century

During the mid-Qing period, sects of popular Buddhism which the Japanese authorities would have later lumped together with the religions of fasting (zhāijiāo) because of their vegetarian prescriptions, began to send missionaries from the mainland to Taiwan.[8] They were more successful in attracting converts than either pure Buddhism or Taoism.[8] Japanese researches of the early colonial period identified zhaijiao sects as a line of the Linji school of Chan Buddhism, although contemporary scholars know that they were centered on a female creator deity, Wusheng Laomu, and identify them as a branch of Luoism self-identifying as a form of Buddhism free of ordained clergy.[8] Zhaijiao sects identify the sangha as the community of believers, not as a separate clergy.[9]

Apart from zhaijiao Buddhist sects, other folk religious sects, that were mistakenly classed as Buddhist by the Japanese government, were active in Taiwan.[10] The most prominent were the three religions of fasting: the Jinchuang sect, the Longhua sect, and Xiantiandao (this last arrived in the mid-19th century).[10]

20th century—Japanese rule

In 1895 the Manchu government ceded Taiwan to Japan as part of the terms of surrender following the First Sino-Japanese War.[10] During the fifty-one years of Japanese rule, governors enacted regulations for the activities of "native religions".[11] During a first period from 1895 to 1915, the Japanese adopted a laissez-faire policy towards native religions.[11] During a second phase from 1915 to 1937, the government tried to vigorously investigate and regulate local religions.[11] A third period, coinciding with the outbreak of hostilities between Japan and mainland China, saw the Japanese government start a "Japanisation movement" (Japanese: 皇民化運動 Hepburn: kōminka undō) that included a "temple-restructuring movement" (寺廟整理運動 jibyō seiri undō).[11]

Buddhism, as a shared heritage of China and Japan, received better treatment than Chinese folk religion and Taoism.[12] Some Taiwanese Buddhist groups cooperated with the Japanese government, and Japanese Buddhist sects sent missionaries to Taiwan and even worked with zhaijiao Buddhist groups.[13] However, given the profound differences between Chinese and Japanese Buddhist traditions (among others, Japanese priests marry, eat meat and drink wine, all of which Chinese monks abstain from), the "Japanisation" of Chinese Buddhism was resisted by Taiwanese Buddhist communities.[14]

In 1915 Japanese religious policies in Taiwan changed after the "Xilai Hermitage incident".[14] The hermitage was a zhaijiao Buddhist hall where follower Yu Qingfang started an anti-Japanese uprising, in which many other folk religious and Taoist sects took part.[14] The Japanese government discovered the plot and Yu Qingfang was executed in a speedy trial together with ninety-four other followers.[14]

After the incident, the Japanese government became suspicious of what it called Taiwan's "old religious customs" (kyūkan shūkyō).[14] The government began to investigate, register and regulate local temples, and it created islandwide Buddhist religious associations—into which even zhaijiao Buddhist groups were enrolled—which charters recommended loyalty to the government.[15]

In 1937, after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Tokyo ordered the rapid acculturation of the peoples of Japan's colonies.[16] This included an effort to wean people away from Chinese traditional religion and into the nexus of State Shinto.[16] Many Shinto shrines were established in Taiwan. Chinese family altars were replaced with kamidana and butsudan, and a Japanese calendar of religious festivals was introduced.[16]

The subsequent "temples' restructuration movement" caused much consternation among the Chinese population and had far-reaching effects.[17] Its inception can be traced to the 1936 "Conference for Improving Popular Customs", that far from promoting a razing of temples discussed measures for a reform and standardisation of Taoist and folk temple practices.[16]

The outbreak of open war between China and Japan in 1937 led to a proscription of practices and even stronger measures, as Japanese officials saw the religious culture centered around folk temples as the major obstacle to Japanisation.[17] Consequently, some local officials began to close and to demolish temples, burning their images, confiscating their cash and real estates, a measure that they called "sending the gods to Heaven".[17] In 1940, when a new governor-general took office, the "temples' restoration movement" was halted.[18]

The Japanese persecution of Chinese folk religion led to an increase of skepticism and loss of faith among the Chinese.[19] As a result of this loss of faith in gods, Japanese police reported a general decline in public morals.[19] The policies also resulted in the disappearance of the small Muslim community until Islam was reintroduced by the Kuomintang with their retreat from mainland China to Taiwan after the end of Chinese Civil War in 1949.[20]

Another effect of the Japanese colonisation of Taiwan in the field of its religious life was produced by the modernisation of infrastructures.[21] Before the 20th century the travel infrastructure of Taiwan was not very developed, and it was difficult for people to move from a part of the island to another.[21] The Japanese quickly constructed a network of railroads connecting all regions of the island.[21] In the field of religion, this promoted the rise in importance of some Buddhist, Taoist or folk temples as island-wide pilgrimage sites.[21] During this time, some gods lost their locative and sub-ethnic nature and became more "pan-Taiwanese".[22]

Republic of China—1945 onwards

In 1945, after World War II, Taiwan was handed over to the Republic of China through the Japanese Instrument of Surrender. The People's Republic of China was established four years later in mainland China under the Communist Party of China.

The rapid economic growth of Taiwan since the 1970s and 1980s ("Taiwan Miracle") accompanied by a quick renewal of Chinese folk religion, challenging Max Weber's theories on secularisation and disenchantment, has led many scholars to investigate how the cultural factor of folk religion—with its emphasis on values like loyalty, its social network of temples and gods' societies—may have contributed to the economic development.[23] During the same period of time, folk religions have developed ties with environmental causes.[24] Chinese salvationist religions (such as earlier Xiantiandao) have become increasingly popular in Taiwan since 1945, although some of them were illegal until the 1980s.[25]

After the 1950s, and especially since the 1970s, there has also been a significant growth of Buddhism.[26] Chinese Buddhism has developed into distinctively new forms with the foundation of movements like the Tzu Chi, the Fo Guang Shan and the Dharma Drum Mountain, which follow the philosophy of Humanistic Buddhism which started in China in the early 20th century.[27] Tibetan Buddhism has also been imported to the island.[27] The most recent times have witnessed an increasing cooperation between religious groups in Taiwan and mainland China.[28][29]

Religions

Main religions

Chinese folk religion

Chinese traditional or folk religion define the collection of grassroots ethnic religious and spiritual experiences, disciplines, beliefs and practices of the Han Chinese. It is primarily focused on worship of the Chinese gods (shen) or spirits, which can be nature deities, city deities or tutelary deities of other human groups, national deities, cultural heroes and demigods, ancestors and progenitors, deities of the kinship. Holy narratives regarding some of these gods are codified into the body of Chinese mythology.[30][31]

Chinese folk religion in Taiwan is framed by the ritual ministry exerted by the Zhengyi Taoist clergy (sanju daoshi), independent orders of fashi (non-Taoist ritual masters), and tongji media. The Chinese folk religion of Taiwan has characteristic features, such as Wang Ye worship.[32] Even though Falun Gong is banned in China, people in Taiwan are free to practice it.[33]

Taoism and Confucianism

Taoism in Taiwan is almost entirely entwined with folk religion,[34] as it is mostly of the Zhengyi school in which priests function as ritual ministers of local communities' cults.[34] Taiwanese Taoism lacks a contemplative, ascetic and monastic tradition such as northern China's Quanzhen Taoism. The leadership of Celestial Masters has its see on the island, and nowadays it is split into at least three lines competing to head the Taoist community.[34]

Politicians of all parties appear at Taoist temples during campaigns, using them for political gatherings.[34] Despite this and the contention of sects for leadership, there is no overarching structure for authority over all Taoists in Taiwan.[34] According to the 2005 census, to that year 7.6 million people identified as Taoists (33% of the population).[1] As of 2015, there are currently 9,485 registered Taoist temples in Taiwan, or 78.35% of all registered temples.[35]

Confucianism is present in Taiwan in the form of many associations and temples and shrines for the worship of Confucius.[36] 0.7% of the population of Taiwan adheres to Xuanyuanism, which is a Confucian-based religion worshipping Huangdi as the symbol of God.[37]

Buddhism

.jpg)

Buddhism was introduced to Taiwan in the mid-Qing dynasty (18th century) through the zhaijiao popular sects.[8] Several forms of Buddhism have thrived on Taiwan ever since. During the Japanese occupation, Japanese schools of Buddhism (such as Shingon Buddhism, Jōdo Shinshū, Nichiren Shū) gained influence over many Taiwanese Buddhist temples as part of the Japanese policy of cultural assimilation.[13]

Although many Buddhist communities affiliated themselves with Japanese sects for protection, they largely retained Chinese Buddhist practices. For instance the Japanisation of Chinese Buddhism, the introduction of clerical marriage and the practice of eating meat and drinking wine, was not as successful as in the Buddhist tradition of occupied Korea.[13]

Following the end of World War II and the establishment of the Republic of China on the island, many monks from mainland China emigrated to Taiwan, including Yinshun (印順). They have given significant contribution to the development of Chinese Buddhism on the island.

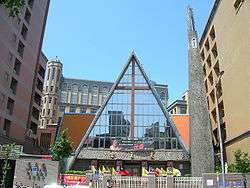

The Buddhist Association of the Republic of China remained the dominant Buddhist organization until the end of government restriction of religions in the 1980s. Today there are several large Humanistic Buddhist-oriented organisations in Taiwan, including the Dharma Drum Mountain (Făgŭshān 法鼓山) founded by Sheng Yen (聖嚴), Buddha's Light International (Fógŭangshān 佛光山) founded by Hsing Yun (星雲), and the Tzu Chi Foundation (Cíjì jījīnhùi 慈濟基金會) founded by Cheng Yen (證嚴法師).

The zhaijiao Buddhist groups maintain an influence in society. In the latest times, also non-Chinese forms of Buddhism, such as Tibetan Buddhism and Soka Gakkai Nichiren Buddhism have expanded in Taiwan.[27] Adherence to Buddhism has grown significantly in Taiwan since the 1980s.[26] From 800.000 in 1983, the number of Buddhists has expanded to 4.9 million in 1995 and subsequently to 8 million (35% of the population) in 2005.[38]

Minor religions

Bahá'í Faith

The history of the Bahá'í Faith (Chinese: 巴哈伊教; pinyin: Bāhāyījiào) in Taiwan began after the religion entered areas of China[39] and nearby Japan.[40] The first Bahá'ís arrived in Taiwan in 1949[41] and the first of these to have become a Bahá'í was Jerome Chu (Chu Yao-lung) in 1945 while visiting the United States. By May 1955 there were eighteen Bahá'ís in six localities across Taiwan. The first Local Spiritual Assembly in Taiwan was elected in Tainan in 1956. The National Spiritual Assembly was first elected in 1967 when there were local assemblies in Taipei, Tainan, Hualien, and Pingtung. Around 2005 the Bahá'ís showed up in the national census with 16,000 members and 13 assemblies.[1]

Christianity

Christianity in Taiwan constitutes 3.9% of the population according to the census of 2005.[1] Christians on the island include approximately 600,000 Protestants, 300,000 Catholics and a small number of Mormons.[1]

Despite its minority status, many of the early political leaders of the Republic of China were Christians. For instance, George Leslie Mackay was a Presbyterian and Nitobe Inazō was a Methodist later converted to Quakerism. Several Republic of China presidents have been at least nominal Christians, including Sun Yat-sen who was a Congregationalist, Chiang Kai-shek, Chiang Ching-kuo (both were Methodists), Lee Teng-hui who is a Presbyterian.

Indeed, Christianity in Taiwan has been on the decline in 1970s, after a strong growth from 1950 to the 1960s.[42]

Islam

Though Islam originated in the Arabian Peninsula, it had spread eastward to China as early as the 7th century AD. Muslim merchants married local Chinese women, creating a new Chinese ethnic group called the Hui people. Islam first reached Taiwan in the 17th century when Muslim families from the southern China's coastal province of Fujian accompanied Koxinga on his invasion to oust the Dutch from Taiwan.

During the Chinese Civil War, some 20,000 Muslims, mostly soldiers and civil servants, fled mainland China with the Kuomintang to Taiwan. Since the 1980s, thousands of Muslims from Myanmar and Thailand, who are descendants of soldiers who fled Yunnan as a result of the communist takeover, migrated to Taiwan in search of a better life. In more recent years, there has been a rise in Indonesian workers to Taiwan. According to the census of 2005, there are 58,000 Muslims in Taiwan.[1]

Judaism

There has been a Jewish community in Taiwan since the 1950s.[43] Since 2011, there has been a Chabad in Taipei.[44]

Census statistics

The table shows official statistics on religion issued by the Department of Civil Affairs, Ministry of the Interior ("MOI"), in 2005. The Taiwanese government recognizes 26 religions in Taiwan.[1] The statistics are reported by the various religious organizations to the MOI:[1][45]

| Religion | Members | % of total population | Temples & churches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhism (佛教) (including Tantric Buddhism) | 8,086,000 | 35.1% | 4,006 |

| Taoism (道教) | 7,600,000 | 33.0% | 18,274 |

| Yiguandao (一貫道) | 810,000 | 3.5% | 3,260 |

| Protestantism (基督新教) | 605,000 | 2.6% | 3,609 |

| Roman Catholic (羅馬天主教) | 298,000 | 1.3% | 1,151 |

| Tiandi teaching (天帝教) | 298,000 | 1.3% | 50 |

| Miledadao (彌勒大道) | 250,000 | 1.1% | 2,200 |

| Tiande teaching (天德教) | 200,000 | 0.9% | 14 |

| Zailiism/Liism (理教) | 186,000 | 0.8% | 138 |

| Xuanyuanism (軒轅教) | 152,700 | 0.7% | 22 |

| Islam (伊斯蘭教) | 58,000 | 0.3% | 7 |

| Mormonism (耶穌基督後期聖徒教會) | 51,090 | 0.2% | 54 |

| Tenriism (天理教) | 35,000 | 0.2% | 153 |

| Maitreya King of the Universe (宇宙彌勒皇教) | 35,000 | 0.2% | 12 |

| Haizidao (亥子道) | 30,000 | 0.1% | 55 |

| Scientology (山達基教會) | 20,000 | < 0.1% | 7 |

| Bahá'í Faith (巴哈伊教) | 16,000 | < 0.1% | 13 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses (耶和華見證人) | 9,256 | < 0.1% | 85 |

| True School of the Mysterious Door (玄門真宗) | 5,000 | < 0.1% | 5 |

| Chinese Holy Church (中華聖教) | 3,200 | < 0.1% | 7 |

| Mahikari (真光教團) | 1,000 | < 0.1% | 9 |

| Salvationism of the Ancient Heaven (先天救教) | 1,000 | < 0.1% | 6 |

| Huang Zhong (黃中) | 1,000 | < 0.1% | 1 |

| Dayi teaching (大易教) | 1,000 | < 0.1% | 1 |

| Total religious population | 18,724,823 | 81.3% | 33,223 |

| Total population | 23,036,087 | 100% | - |

The figures for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are not from the MOI rather they are based on self reported data from LDS Newsroom.[46]

The figures for Jehovah's Witnesses are not from the MOI rather they are based on the Witnesses own 2007 Service Year Report.[47]

See also

- Demographics of Taiwan

- Religion in China

- Chinese folk religion

- Religion in Hong Kong

- Religion in Macau

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Taiwan Yearbook 2006". Government of Information Office. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 11.

- ↑ Rubinstein (2014), p. 347.

- ↑ Shepherd, John R. (1986). "Sinicized Siraya Worship of A-li-tsu". Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica. Taipei: Academia Sinica (58): 1–81.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 12.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 13-14.

- 1 2 3 4 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 16.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 19.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Clart & Jones (2003), pp. 20-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 21.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), pp. 21-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 25.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 26.

- 1 2 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 27.

- ↑ Peter G. Gowing (July–August 1970). "Islam in Taiwan". SAUDI ARAMCO World. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Clart & Jones (2003), p. 29.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), pp. 29-31.

- ↑ Rubinstein (2014), p. 351.

- ↑ Rubinstein (2014), p. 355.

- ↑ Rubinstein (2014), p. 346.

- 1 2 Rubinstein (2014), p. 356.

- 1 2 3 Rubinstein (2014), p. 357.

- ↑ Rubinstein (2014), p. 360.

- ↑ Brown & Cheng (2012), passim.

- ↑ J. J. M. de Groot. Religion in China: Universism a Key to the Study of Taoism and Confucianism. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 141794658X

- ↑ P. Koslowski. Philosophy Bridging the World Religions. Book 5 in: A Discourse of the World Religions. Springer, 2003. ISBN 1402006489. p. 110.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), Ch. 5 (p. 98-124).

- ↑ 中央管法輪功廣告,台南市長認為不妥。 (in Chinese). Executive Yuan.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown & Cheng (2012), p. 68.

- ↑ Lee Hsin-fang; Chung, Jake (15 Jul 2015). "Tainan has most of nation's 12,106 temples". Taipei Times. p. 5.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 48.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 60.

- ↑ Clart & Jones (2003), p. 186.

- ↑ Hassall, Graham (January 2000). "The Bahá'í Faith in Hong Kong". Official Website of the Bahá'ís of Hong Kong. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Hong Kong. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ↑ Baldwin Alexander, Agnes; R. Sims, Barbara (ed.) (1977). "History of the Bahá'í Faith in Japan 1914-1938". Japan: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, Osaka, Japan.

- ↑ R. Sims, Barbara (1994). The Taiwan Bahá'í Chronicle: A Historical Record of the Early Days of the Bahá'í Faith in Taiwan. Tokyo: Bahá'í Publishing Trust of Japan.

- ↑ Murray A. Rubinstein. The Other Taiwan: 1945 To the Present. M. E. Sharpe, 1994. p. 94

- ↑ Yiu, Cody (14 Feb 2005). "Taipei's Jewish community has deep roots". Taipei Times. p. 2. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Cashman, Greer Fay (January 14, 2012). "Energetic Chabad rabbi nourishes Jewish Taipei". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "2006 Report on International Religious Freedom". U.S. Department of State. 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ↑ "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Taiwan Country Profile".

- ↑ "Jehovah's Witnesses: Interactive Map of the Worldwide Work".

Sources

- Rubinstein, Murray A. (2014). Taiwan: A New History. Routledge. ISBN 9780765614957.

- Clart, Philip; Jones, Charles B., eds. (2003). Religion in modern Taiwan: tradition and innovation in a changing society. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824825645.

- Clart, Philip; Ownby, David; Wang, Chien-chuan (2010). Text and Context: Redemptive Societies in the History of Religions of Modern and Contemporary China. University of Leipzig.

- Brown, Deborah A.; Cheng, Tun-jen (January 2012). "Religious Relations across the Taiwan Strait: Patterns, Alignments, and Political Effects" (PDF). Orbis. 56 (1): 60–81. doi:10.1016/j.orbis.2011.10.004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Religion in Taiwan. |