Kansas Turnpike

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by KTA | ||||

| Length: | 236 mi[1] (380 km) | |||

| Existed: | October 1956 – present | |||

| Component highways: | ||||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end: |

| |||

| East end: |

| |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

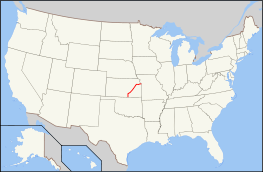

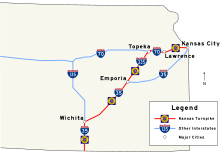

The Kansas Turnpike is a 236-mile-long (380 km), freeway-standard toll road that lies entirely within the U.S. state of Kansas. It runs in a general southwest–northeast direction from the Oklahoma border to Kansas City. It passes through several major Kansas cities, including Wichita, Topeka, and Lawrence. The turnpike is owned and maintained by the Kansas Turnpike Authority (KTA), which is headquartered in Wichita.

The Kansas Turnpike was built from 1954 to 1956, predating the Interstate Highway System. While not part of the system's early plans, the turnpike was eventually incorporated into the Interstate system in late 1956, and is designated today as four different Interstate Highway routes: I-35, I-335, I-470, and I-70. The turnpike also carries a piece of U.S. Routes 24 and 40 in Kansas City.

Because it predates the Interstate Highway System, the road is not engineered to current Interstate Highway standards, and notably lacks a regulation-width median. To reduce the risk of head-on collisions, the Kansas Turnpike now has a continuous, permanent Jersey barrier in the median over its entire length. On opening, there was no fixed speed limit on the highway; drivers were merely asked to keep to a "reasonable and proper" limit, although shortly afterward signs were erected in certain stretches indicating a maximum speed of 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). From 1970 to 1974 and again since 2011, the turnpike's speed limit has been set at 75 mph (120 km/h); that limit during the earlier period applied only during daytime hours.

Around 120,000 drivers use the turnpike daily. The road features numerous services, including a travel radio station and six service areas. One of these service areas is notable for the presence of a memorial to University of Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne, who died near the current highway's route. The turnpike is self-sustaining; it derives its entire revenue from the tolls collected and requires no tax money for maintenance or administration.

History

Early history

Early federal plans for a nationwide system of interregional highways did not include a route along or near the present turnpike, instead connecting Oklahoma City and Kansas City via southeastern Kansas and U.S. Route 69.[2] By the mid-1940s, this route had shifted to roughly the present Interstate 35 alignment, serving Wichita. The only major difference from the present route was between Wichita and Emporia, where the highway ran north to Newton before turning northeast along U.S. Route 50.[3]

In the early 1950s, toll roads were gaining in popularity as a mechanism for funding new superhighways. This trend started with the Pennsylvania Turnpike in 1940, which was mimicked by other toll roads in New York, New Jersey, several New England states, Ohio, and Colorado. In October 1951, the Highway Council of the Kansas Chamber of Commerce researched the possibility of integrating the state into a potential cross-country turnpike system. Eastern Kansas was also included in an interstate turnpike system stretching from Galveston, Texas to Saint Louis, Missouri, via Kansas City, that was proposed by Oklahoma governor Johnston Murray.[4] Many firms from construction industries, as well as those concerned about the state's economic development, worked to have legislation passed to allow the turnpike to be constructed. Governor Ed Arn and Gale Moss, the State Highway Director, were two major proponents of the turnpike concept.[5]

The turnpike idea was an attractive one because initial construction was to be financed by the private sector via sales of revenue bonds, allowing state highway funds to be used for other important projects. The new toll road would also reduce traffic, and thus maintenance costs, on existing roads. There was also a concern that if Kansas lagged behind in turnpike construction, it might be bypassed by toll roads in other states, leaving it at an economic disadvantage.[4] The toll concept also had the benefit of ultimately putting the financial burden on the drivers who actually used the road, instead of using tax revenue that had been collected from residents statewide.[5] There was a some opposition to the plan, from both government officials and citizens, due to concerns that the toll revenue might not cover the repayments to investors, bankrupting the turnpike authority and burdening the state government with the remaining debt. There were also worries about the possibility of the turnpike requiring maintenance before the bonds had been repaid. Some critics also felt that the high speeds typical of turnpike driving were unsafe.[4] As right-of-way for the project was obtained, the turnpike drew opposition from farmers and ranchers, who objected to the turnpike bisecting their property, making it difficult to access disjointed parcels of land.[5]

The Kansas Chamber of Commerce held "turnpike clinics" in several locations across Kansas in 1952, reporting an overwhelmingly positive reception from the public.[4] The Kansas Turnpike Act, defining a turnpike from Oklahoma to Kansas City, became effective April 7, 1953.[6] It created the Kansas Turnpike Authority, with Gale Moss selected as its first chairman. With a budget of only $25,000 (about $570,000 in 2015[7]), KTA's first office was a former barbershop in the Kansas State Capitol.[4]

Given Oklahoma's plans to build a turnpike north from Oklahoma City to the Kansas state line, and taking into account traffic flow maps prepared by the highway department, a preliminary route was chosen connecting the proposed Oklahoma turnpike to Kansas City via Wichita and Topeka. A second route extending from Topeka to Salina, and further west to the Colorado state line (the modern-day I-70 corridor) was also studied. Over 173,000 drivers were surveyed to determine how many of them would be willing to use the two proposed routes in order to establish their profitability. While the western Kansas route was determined not to be feasible, the Oklahoma–Kansas City route was projected to generate a total revenue of $9 million in 1957 (about $181 million in 2015 dollars[7]). After considering a number of different alignments, including one bypassing Topeka via the present route of I-35, the state decided on an "airline" route between Wichita and Topeka. From Wichita south, the turnpike was to parallel U.S. Route 81, continuing into Oklahoma; the interchange with U.S. Route 166 at South Haven was included to provide an outlet if Oklahoma lagged in its construction. The turnpike was to parallel U.S. Route 40 from Topeka to Kansas City. The Kansas City end was set at 18th Street and Muncie Boulevard, which was to be extended and upgraded to a freeway (the Muncie Expressway) to the Intercity Viaduct by the state.[4]

After a ruling from the Kansas Supreme Court that found that the KTA could issue bonds and oversee the construction and administration of the turnpike, the turnpike authority sold $160 million (around $3.22 billion in 2015 dollars[7]) in revenue bonds in September 1954. KTA bonds were quickly bought by investors, who were attracted by the Kansas Turnpike's low construction costs—only one-third of that of turnpikes in other states—and projections showing that enough tolls would be collected to pay off investors after nineteen years.[4]

Ground was broken on December 31, 1954 at the Kansas River bridge near Lawrence.[8] Construction of the entire length of the turnpike was scheduled to take place all at once, with the turnpike partitioned into 14 parts, and the overall length also divided into 43 smaller portions. The Turnpike Authority sent out letters en masse to the affected landowners, offering a price and referring appeals to the local district court, which typically valued the land at a lesser amount; this methodology was not without criticism.[9] During the construction period, the state highway department suffered a "brain drain" as many staffers resigned to take up KTA jobs, which paid better salaries (Chairman Moss's KTA salary was three times that of his salary as director of highways) and offered more exciting challenges.[4]

After almost 22 months of construction, the road was opened for a day of free travel on October 20, 1956 between 6 a.m. and 2 p.m.[10] An estimated 12,000 to 15,000 cars traveled on the turnpike. Many of those motorists traveled to Lawrence for a football game between the University of Kansas and University of Oklahoma.[11] Official opening ceremonies were held at interchanges in each of the three major cities on October 25. The Kansas City celebration included Gene Autry jumping his horse through a large paper map of the turnpike. John Masefield, the British Poet Laureate, wrote a tribute to commemorate the occasion.[4] On the first day after the official opening, 7,197 vehicles traveled the turnpike, with 81 toll collectors and 50 maintenance workers on duty.[9] The turnpike originally had 14 interchanges; by 2012, there were 22.[12]

The southern terminus

Despite Oklahoma's role in instigating the construction of the Kansas Turnpike, its plans for a connecting turnpike fell through. The Oklahoma Turnpike Authority (OTA) had not performed a traffic study, as KTA had, to prove that the proposed Oklahoma turnpike would be profitable. Oklahoma also suffered from a poorer credit rating than did Kansas. Additionally, by this time many states' turnpike authorities were competing in the bond markets for investor dollars. All of these issues combined made it difficult for OTA to issue bonds for its toll road. When funding had been obtained, political issues stalled the proposed toll road further.[4]

With no counterpart to the south, the Kansas Turnpike ended at the state line, at an at-grade intersection with E0010 Road.[lower-alpha 1][14] Just across the state line was an oat field, into which many inattentive motorists crashed. This abrupt end became nationally famous after Wyoming governor Milward L. Simpson and his wife crashed in mid-1957. The oat farmer plowed the field to provide a safer landing, and the KTA was persuaded to install a huge wooden barrier at the end of the highway. However, within a day, three more drivers had crashed and destroyed the barrier, so the KTA closed the turnpike south of the South Haven interchange. KTA provided the state of Oklahoma with financial aid to construct its portion of a temporary road leading to the interchange.[4] The lack of continuity in the highway was one of the primary reasons that the road did not generate much revenue in the years following the opening; another reason was a lack of education on the part of motorists as to the concept of a toll road.[15]

Although Oklahoma's plans to construct a toll road from the southern end of the Kansas Turnpike at the state line to Oklahoma City did not materialize, a year and a half after the opening of the turnpike, a 5-mile (8.0 km) connection to US 177 was put into service. Eventually I-35 was completed south to Oklahoma City.[15]

Recent history

While the initial turnpike was still being built, the KTA authorized four feasibility studies in October 1954. Three of them—a spur to Leavenworth and Saint Joseph, Missouri, a spur from Wichita to Hutchinson, Great Bend and Hays, and a new Intercity Viaduct to Kansas City, Missouri—did not go anywhere. But the fourth proposal, a toll bridge on 18th Street in Kansas City, was pushed through, and the KTA agreed to build the turnpike in early 1956. The 18th Street Expressway, running south from the turnpike's east end over the Kansas River, opened in 1959, improving access to northeast Johnson County.[4]

As the turnpike did not use any state tax revenue for maintenance, the pavement began to deteriorate rapidly, and crews faced difficulty keeping up with the snow in winter conditions in a winter storm during 1960. In the early 1960s, many senior positions in the Kansas Turnpike Authority were cut, and thanks to this and other austerity measures such as targeting maintenance to save costs in the future, the turnpike slowly became profitable.[15] By 1966, it was clear that the turnpike had not been built to the higher standards of the Interstate Highway system; the roadway had developed ruts and other issues due to deferred maintenance. To temporarily fix the problem, a layer of asphalt oil and a layer of sand and asphalt was used to fill in the ruts, and graded rock coated with asphalt was used to seal the road. Since the road had been originally constructed at the same time, and not built in segments over a period of time, similar maintenance issues appeared along the whole length of the road at the same time. Bridges and pavement were repaired on a rotating basis, to stagger the cost of needed repairs. The bridge over the Kansas River was widened and replaced after 1973. As economic conditions improved for the Authority, equipment was slowly replaced, and workers were given pay increases, both of which were badly needed.[16]

In June 1956, the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 was signed into law, granting funding to the nationwide Interstate Highway System. Without its Oklahoma link, the Kansas Turnpike was in danger of being bypassed by the Interstate System entirely. However, at the end of 1956, the Bureau of Public Roads and the state of Kansas agreed to route I-35 along the turnpike south of Emporia and I-70 along the piece east of Topeka. The state insisted on a separate Emporia–Kansas City alignment, and the mileage that would have been used to build I-35 from Wichita to Emporia via Newton was instead used for Interstate 35W (now Interstate 135) from Wichita via Newton to Salina.[4] Oklahoma's first piece of Interstate 35, from the state line to U.S. Highway 177 at Braman, opened April 22, 1958.[4][lower-alpha 2]

The East Topeka interchange was completely rebuilt in the late 1990s, with a goal of rerouting I-70 and improving access to the turnpike. The design was completed in 1997, and the project was finished in 2001 at a cost of $98.6 million in 1999 dollars.[19]

On the evening of April 6, 2002, a grease fire broke out in the Hardee's restaurant at the Belle Plaine service plaza. Exacerbated by heavy winds, the fire destroyed the building, which also contained a travel information center. Four fire departments responded to the scene. The assistant fire chief and fire chief of the Wellington Fire Department gave conflicting statements on whether the unavailability of the Wellington water tower, which had been emptied while it was being repainted, had hampered efforts to extinguish the blaze. The fire burned for three hours, with hot spots still smoldering the following day. No injuries were reported.[20][21] The fire caused $2 million in damages. The service plaza was rebuilt, with a reopening celebration occurring on July 24, 2003.[22]

A 390-year flood event took place on the night of August 30, 2003, at the Kansas Turnpike's crossing of Jacobs Creek, a tributary of the Cottonwood River 11 miles (18 km) southwest of Emporia (turnpike milepost 116). A thunderstorm that evening dropped large amounts of rain in the area, with a gauge at Plymouth reporting 7.1 inches (18 cm) of rainfall in a 24-hour period. The culvert carrying Jacobs Creek under the turnpike quickly exceeded its capacity, and water rose onto the turnpike. A pool of water four feet (1.2 m) deep formed on the northbound lanes; the concrete median barrier initially prevented most of the water from crossing to the southbound lanes. Seven cars, all headed northbound, stalled in the floodwater. The median barrier then gave way, sweeping the stalled cars across the southbound lanes and down the creek as far as 1 1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) from the highway. Six people died in the flood.[23][24]

Tolls

As of 2014, the passenger or passengers of two-axle vehicles (such as cars and motorcycles) pay a total of $12.00 to travel the entire length of the turnpike. Tolls are calculated based on the length of the route traveled, and the toll is as little as 30¢ for motorists driving only a short distance (3 miles (4.8 km), for example) on the turnpike. Drivers in vehicles with more than two axles, such as truckers, pay higher tolls.[25]

The turnpike runs on a ticket-based collection system. When entering the turnpike, either at one of the termini or at an interchange, a driver is issued a ticket which indicates the toll plaza at which they entered. When leaving the turnpike, this ticket is used to determine the amount of the toll. If a motorist presents a ticket at the same toll plaza it was issued from, the KTA charges a "per-minute" fare if the trip was more than fifteen minutes. Should the ticket be lost, or should the trip take over eighteen hours to complete, the driver must pay the highest possible toll for that exit.[12][26]

As an alternative to using tickets, motorists can order a transponder, known as a K-TAG. K-TAG customers can proceed slowly through the toll plaza without stopping to collect a ticket or pay toll. The toll is instead paid through one of two payment plans. K-TAG Classic, intended for frequent turnpike users, requires the customer to maintain a prepaid account, from which funds are drawn as needed. The plan intended for intermittent users, My K-TAG, requires an active credit card. My K-TAG keeps track of the tolls accrued by the customer, and automatically charges the user's credit card monthly. K-TAG Classic accounts are subject to a $1 monthly fee per tag, while My K-TAG account holders can get up to five tags for free. Tolls for K-TAG users are lower than for cash customers, so a two-axle vehicle with a K-TAG is charged only $10.20 to travel the entire length of the turnpike.[25] K-TAG Classic users also receive an additional 10-percent discount on tolls.[27] K-TAGs are available for purchase at select Walgreens, Dillons, and AAA locations.

K-TAG was introduced in 1995;[28] the system was internally designed and is internally run, instead of being contracted to another company, saving additional overhead costs.[19] The Kansas Turnpike is completely self-sustaining. All costs are paid for by the tolls collected; no tax money is used for construction, maintenance, or administration. KTA estimates that 120,000 drivers use the turnpike each day.[29]

Interoperability

The K-TAG is compatible with PikePass in neighboring Oklahoma. However, K-TAG is not compatible with any other systems, including the E-ZPass system in the Eastern United States.[30][31] Around the 3rd quarter of 2017, the K-TAG will become compatible with the Toll Tags in Texas; the Texas Department of Transportation (TxTag),[32] the Harris County Toll Road Authority (EZ TAG) [32] and the North Texas Tollway Authority (Toll Tag).[32]

Route description

The Kansas Turnpike is 236 miles (380 km) long.[1] As of 2014 the Kansas Turnpike has 22 interchanges and two barrier toll plazas.[12] Many of the interchanges are designed as trumpet interchanges with a connector road to the crossroad, for easy placement of a single toll plaza on the connector.[33]

Exit numbers were originally sequential[34] but are assigned today by mileage from south to east, the same numbering system used by the majority of U.S. states for their Interstate Highways as well. After passing the Bonner Springs interchange, exit numbers change to match the mileage of Interstate 70 (I-70) east from the Colorado border, which is also used on I-70 west of the turnpike.[33] This results in discontinuous exit numbers on I-70.

Oklahoma state line to Emporia

The first 127 miles (204 km) of the highway, between its southern terminus at the Oklahoma border and Emporia, Kansas, are designated as Interstate 35 (I-35). The Kansas Turnpike is the only tolled section on this Interstate. The turnpike runs due north and south between its southern terminus and Wichita. This stretch of the highway runs parallel to U.S. Route 81 (US-81), which lies to the west of the turnpike.[35]

The Kansas Turnpike begins at the Oklahoma state line north of Braman, Oklahoma. This is also the point at which I-35 crosses from Kay County to Sumner County. The turnpike proceeds due north from the state line, with no interchanges for its first four miles (6.4 km) in Kansas.[35] The southernmost interchange on the turnpike is Exit 4 (South Haven[36]), which serves US-166. US-166 heads east to Arkansas City and west to US-81 at South Haven. This interchange is a four-ramp folded diamond with ramps in the southeast and northwest quadrants. It has no toll plazas, as it lies south of the southern barrier toll. Northbound traffic must exit at US-166 to avoid paying a toll. Initially, the interchange provided only a southbound exit and northbound entrance,[37] forcing drivers who did not wish to pay a toll to leave I-35 in Oklahoma. By 1976 the other two ramps had been added.[36]

From Exit 4, the turnpike continues on a due north course, crossing Slate Creek, before coming to the Southern Terminal barrier toll plaza,[35] where tickets are issued for all northbound traffic and fares are collected from southbound traffic. The next interchange north of the toll plaza is Exit 19 (Wellington[38]), serving US-160, which heads west to Wellington, the county seat of Sumner County, and east to Winfield, the seat of adjoining Cowley County. It is the first of many trumpet interchanges, serving the surface road via a connector road with a toll plaza. When the turnpike first opened, the US-160 interchange was a reversed diamond with four loop ramps, so that all traffic using the interchange had to pass under the bridge and thus through the toll plaza.[38][39] The new configuration was built c. 1988.[40]

The freeway takes a brief jog to the northeast before crossing over a Burlington Northern Santa Fe rail line southeast of Riverdale. In the median at mile 26[41] is the Belle Plaine Service Area. North of the service plaza, the highway bridges the Ninnescah River and then K-55. No interchange is present to allow turnpike travelers to connect to the K-55.[35]

The turnpike's next interchange is Exit 33 (Mulvane[42]), which connects to K-53 via a trumpet ramp, just east of the west end of K-53 at US-81. The interchange was built c. 1985.[43] It was reconstructed in 2011 to serve the Kansas Star Casino with roundabouts on each side of the flyover. The east roundabout directs traffic to K-53. The west roundabout directs traffic to the casino. There is now a toll booth on the casino side of the intersection as well as the one on the entrance to K-53.[44] This interchange straddles the Sumner–Sedgwick county line.[35]

In southern Sedgwick County, the Kansas Turnpike enters the Wichita metropolitan area. Exit 39 (Haysville[42]) serves two of Wichita's southern suburbs. This exit is a diamond interchange with a connector road to Grand Avenue, which runs west to U.S. Route 81 and Haysville and east to Derby. It was built c. 1989.[45] Now in Wichita proper, the highway reaches exit 42 (South Wichita[46]), which is the south end of Interstate 135. I-135 heads north through Wichita, the largest city in Kansas, toward Salina; US-81 joins at the first interchange and I-235 begins at the second. The interchange is a simple trumpet with I-135, and opened in 1956 with the turnpike, but the connector ended at 47th Street (now US-81) until c. 1961.[13][47]

After passing exit 42, the turnpike curves away from US-81, turning northeast toward El Dorado and Emporia.[35] It crosses the Arkansas River between Exits 42 and 45. Exit 45 (Wichita, K-15)[48]) is a trumpet connection to K-15 in southern Wichita. It opened in 1956 as one of the original interchanges.[49] As the highway continues northeast through Wichita, it comes to Exit 50 (East Wichita[42]), a double-trumpet connection to the parallel Kellogg Avenue, which carries US-54 and US-400. It is one of the original 1956 interchanges.[50] Exit 53, the final Wichita exit, is a trumpet connection to the K-96 freeway. The connector road junctions K-96 at a four-ramp partial cloverleaf interchange and ends at 127th Street East. The interchange opened c. 1994 along with the nearby piece of K-96.[51]

East of Exit 53, the turnpike passes into Butler County. Exit 57 (Andover[42]) connects to 21st Street northeast of downtown Andover, an eastern suburb of Wichita. (This is the same "21st Street" that runs through Wichita.) The turnpike uses a diamond interchange with the connector road to 70th Street. This interchange opened c. 1985.[52] It crosses the Whitewater River southwest of the Towanda Service Area, located in the median at mile 65.[35][41] From the service area, the highway proceeds north east to Exit 71 (El Dorado[53]), a trumpet connection to K-254 just east of its junction with K-196. The connector originally directly intersected K-254,[53] but it now ends between K-254 and West 6th Avenue, just north of K-254. Exit 71 opened with the original turnpike in 1956.[54] North of El Dorado, Exit 76 (El Dorado) connects the Kansas Turnpike to U.S. Route 77 via a trumpet ramp. It opened c. 1986.[55]

After passing through El Dorado, the Kansas Turnpike crosses the northernmost arms of El Dorado Lake. This marks the turnpike's entry into the Flint Hills, a band of hills in eastern Kansas. The turnpike does not leave this region completely until it reaches Topeka.[33][56] As the highway continues northeast past El Dorado Lake, it runs roughly parallel to the Walnut River to the west, which feeds the reservoir, and K-177 to the east.[35] Northwest of the town of Cassoday, K-177 finally crosses the turnpike, with Exit 92 (Cassoday[57]), a diamond interchange, providing a connector to the state highway. The interchange was not present when the turnpike opened in 1956,[58] but was built soon after as an east-facing folded diamond with two separate toll plazas.[57] The present configuration was built c. 1995.[59] Near this interchange, the turnpike crosses the Walnut River.[35]

Northeast of the Cassoday interchange, the Kansas Turnpike enters Chase County. In the median at mile 97, just north of the county line, is the Matfield Green Service Area.[41] Approximately 13.7 miles (22.0 km) northeast of the service area, an interchange provides access to a set of cattle pens southeast of Bazaar.[60] Other than these two service exits, there are no interchanges within Chase County; upon leaving it, the turnpike passes into Lyon County.[35]

The next interchange along the turnpike is Exit 127 (Emporia[61]). At this trumpet interchange, Interstate 35 leaves the turnpike to head east through Emporia, the county seat of Lyon County, on its way northeast to Kansas City via Ottawa. Interstate 35 and U.S. Route 50. The interchange, as opened in 1956 with the original turnpike, connected directly to US-50 at Overlander Street;[61] a different configuration opened c. 1966 along with the connecting piece of I-35.[13] In 2005, KTA approved reconstruction of the Emporia interchange to improve connections to US-50, I-35, and the city of Emporia, resulting in the present configuration. This project, funded by the Turnpike Authority, the Kansas Department of Transportation, and the city of Emporia, was completed in 2008.[62]

Emporia to Topeka

| |

|---|---|

| Location: | Emporia–Topeka |

| Length: | 50.13 mi[63] (80.68 km) |

| Existed: | 1987–present |

After the split with I-35, the Kansas Turnpike continues northeast as I-335. However, its exits are numbered as if I-35 had continued along it. This highway exists entirely as a part of the Kansas Turnpike.[33] In fact, until 1987, this stretch of the turnpike was designated solely as the Kansas Turnpike without an Interstate number. It was only after a change in the National Maximum Speed Law, when state legislators were given the authority to raise the speed limits on rural Interstate Highways to 65 mph (105 km/h), that this segment of the Kansas Turnpike was given the I-335 designation so that it could fall under the new law.[64]

Northeast of Emporia, the Emporia service area is located in the median at mile 132.[41] The turnpike continues northeast through the northern reaches of the Flint Hills, coming to an interchange with US-56 near Admire. This interchange, Exit 147, is the only interchange along the I-335 section of the turnpike other than the two end junctions.[33] It is a trumpet connection to US-56, which heads west to Council Grove and east to Osage City, and was one of the original 1956 interchanges.[65]

From the Admire exit, the Kansas Turnpike continues northeast, passing through the southeast corner of Wabaunsee County and the northwestern part of Osage County. The turnpike enters Shawnee County and continues through rural land before it heads into the Topeka area. Here, the roadway has an interchange that serves I-470 and US-75. At this point, I-335 ends and I-470 joins the turnpike as it passes through suburban development in the southeastern part of Topeka. In the eastern portion of the city, the highway reaches an interchange with I-70, US-40, and K-4.[66][67]

Topeka to Kansas City

The remainder of the turnpike runs on I-70 from Topeka to the turnpike's eastern terminus in Kansas City. This is one of only two tolled sections of I-70; the other is on the Pennsylvania Turnpike with I-76.

The turnpike continues east along I-70 and crosses Tecumseh Creek. The Topeka Service Area is located on the north side of the road east of here at mile 188.[41] It is accessed by ramps on the right side of the highway in both directions. Just east of the service area, the turnpike enters Douglas County while passing over US-40 without an interchange. The route then curves to the southeast and runs roughly parallel to US-40. A series of curves takes the turnpike farther east as it reaches Exit 197 (Lecompton[68]), a folded diamond interchange with the western terminus of K-10. After this, the highway continues farther east and enters the city of Lawrence, where it shares a diamond interchange with McDonald Drive at Exit 202 (West Lawrence[69]). McDonald Drive leads to US-59 south of the turnpike. East of here, the highway bends east-northeasterly, crosses the Kansas River, and then intersects US-40 and US-59, which run concurrently, at Exit 204 (East Lawrence[70]).[71]

The Kansas Turnpike then leaves Lawrence and bends to the northeast before leaving Douglas County and entering Leavenworth. It overpasses Mud Creek before passing under K-32. Northeast of here at mile 209, the Lawrence Service Area is located in the median.[41] Afterward, the turnpike has a diamond interchange with 222nd Street, which is signed as Leavenworth County Road 1, at Exit 212 (Tonganoxie/Eudora).[72] The highway then travels northeast and passes through it eastern terminal toll booth. This is the final toll booth on the route travelling east and all vehicles must pay their final toll before continuing. The turnpike then enters Bonner Springs. It crosses Wolf Creek before leaving Leavenworth County and entering Wyandotte County. In Bonner Springs, the turnpike intersects K-7, westbound US-24, westbound US-40, and the southern terminus of US-73 at Exit 224 (Bonner Springs,[73] formerly Exit 223) with a trumpet interchange. The mileposts on the route switch to match those of I-70 after this interchange.[74]

US-24 and US-40 run concurrently with I-70 and the Kansas Turnpike as it heads east toward Kansas City. The first free exit on the turnpike is a diamond interchange with 110th Street at Exit 410. This interchange is located just south of the Kansas Speedway. Just east of here, the route intersects I-435 at Exit 411. This exit uses a cloverleaf interchange with one directional ramp and collector–distributor roads to avoid issues with traffic exiting immediately north of the turnpike. After this interchange, the highway enters Kansas City.[75]

The turnpike's first exit in the city is Exit 414, a diamond interchange with 78th Street. Next, the highway curves slightly to the northeast and intersects the Turner Diagonal at Exit 415, an interchange consisting of a half-cloverleaf for the western ramps and a Y-connection for the eastern ramps that intersects the Turner Diagonal at a trumpet interchange north of the turnpike. East of here, the route has a diamond interchange with 57th Street at Exit 417. Directly east of 57th Street, the turnpike crosses Brenner Heights Creek. After this, the turnpike continues due east to a fully directional interchange with I-635 at Exit 418.[76]

After this interchange, the freeway bends in a southeastern direction and reaches its final exit, Exit 420. This exit is a cloverleaf interchange with US-69, which is also known as the 18th Street Expressway. At this interchange, US-69 turns east to overlap I-70, US-40, and US-24, and the highways continue east of Exit 420 toward Kansas City, Missouri.[77]

Design

Because the Kansas Turnpike was built before the Interstate Highway System, it is not engineered to current Interstate Highway standards. The turnpike was originally constructed with lanes only 12 feet (3.7 m) wide.[4] Notably, the turnpike was built without a 36-foot (11 m) median. When it opened, the central reservation was a 20-foot (6.1 m) depressed median.[9] Starting in 1985,[16] Jersey barriers were installed along its entire length.[78] As with all other toll roads that predated the Interstate Highway System, the highway is grandfathered from Interstate standards.

Kansas Turnpike mileposts are continuous along the entire length of the turnpike. Mile markers begin at the point where I-35 enters Kansas at the southern border. These numbers are continued along the other three Interstates that make up the turnpike, rather than numbering each Interstate individually, leading to discontinuous numbering on I-70—the exit numbers on tolled I-70 are much lower than those on free I-70.[79]

The majority of the Kansas Turnpike, from the Oklahoma state line to Topeka, was constructed with four-inch (100 mm) asphalt. The 55 miles (89 km) from Topeka to Kansas City was built with Portland cement concrete.[78] Curves along the turnpike are limited to 3° and grades limited to 3%.[78] Early reports said that curves were designed to accommodate speeds of 70 to 75 mph (115 to 120 km/h).[4] When built, the turnpike was designed to allow 18,000-pound (8,200 kg) axle loads.[78] Minimum sight distances were kept at 725 feet (221 m).[78] The 300-foot (91 m) right of way featured fenced edges to prevent cattle from entering the roadway and to discourage toll evasion.[4]

Speed limits

When the turnpike was originally opened, it had no posted speed limit, however "drivers [would] be 'hailed down' if they exceed 80 miles an hour [130 km/h]."[80] In 1970, the speed limit was reduced to 75 mph (120 km/h) during the day and 70 mph (115 km/h) at night; authorities cited accidents caused by excess speed.[81] Nationwide, the speed limit was reduced to 55 mph (90 km/h) on January 2, 1974; Kansas delayed implementing the reduction until the deadline on March 2, 1974.[82]

When Congress allowed states to increase their speed limits to 65 mph (105 km/h), Kansas increased the speed limit on most of the turnpike; the Emporia–Topeka segment did not have an Interstate designation to allow for an increase there. Other sections through urban areas remained at the lower limits as well.[83] The Kansas Department of Transportation requested an Interstate designation for the Emporia–Topeka segment of the turnpike by May 1987,[84] which they received on October 23, 1987, when that section was given the I-335 designation to allow for a 65 mph (105 km/h) speed limit.[85] Later in November 1995, Congress repealed the National Maximum Speed Limit; Kansas initially left their limits alone after the repeal.[86] Legislation that raised the speed limits to 70 mph (115 km/h) took effect on March 22, 1996.[87]

On July 1, 2011, the speed limit on most of the Kansas Turnpike was raised once again to 75 mph (120 km/h) as part of a set of speed limit increases affecting several rural Interstates and U.S. routes throughout Kansas.[88] The minimum speed is 40 mph (65 km/h).[89]

Services

The Kansas Turnpike Authority provides a number of services to help motorists and provide incentives for using the turnpike. KTA broadcasts a travel radio station at 1610 AM from Wellington, Wichita, El Dorado, Cassoday, Emporia, Admire, East Topeka, and West Lawrence. Law enforcement is provided by a separate Turnpike Division of the Kansas Highway Patrol. Motorists needing assistance can use a roadside assistance hotline by dialing *KTA (*582) on a mobile phone. Statewide weather and traffic conditions can be accessed by dialing 511. KTA also provides weather and traffic information on their website.[12] The original service areas were spaced 45 miles (72 km) apart.[9]

There are six service areas located along the highway:

- The Belle Plaine service area (mile 26) opened on July 24, 2003, replacing a previous structure at the site that had been destroyed by a grease fire.[22] It contains a 24-hour gas station and convenience store, a fast food restaurant, a weather kiosk, a Kansas Travel Information Center, and a gift shop.[12]

- The Towanda service area (mile 65) provides a 24-hour gas station and convenience store, a fast food restaurant, and a weather kiosk.[12]

- The Matfield Green service area (mile 97) shares the design of the Towanda service area, and also provides a 24-hour gas station and convenience store, a fast food restaurant, and a weather kiosk.[12] The service area at Matfield Green also contains a 175-square-foot (16.3 m2)[90] memorial to Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne, who died in a 1931 plane crash near Bazaar, Kansas, a few miles north of the service area.[91]

- The Emporia service area (mile 132), like the two service areas to the south, includes a 24-hour gas station and convenience store and a fast food restaurant. Additionally, the facility provides an outdoor exercise area and playground for children.[12]

- The Topeka service area (mile 188) opened in May 2002. This service plaza features a choice of five restaurants (one of which is open 24 hours), as well as a gift shop and a 24-hour gas station and convenience store.[12] Prior to this plaza's opening, a service area was located in the median between exits 182 and 183. It closed in May 2002 when the present Topeka Service Area opened.[92][93]

- The Lawrence service area (mile 209) consists of a 24-hour gas station and convenience store, in addition to a 24-hour fast food restaurant.[12]

Exit list

| County | Location | mi[94] | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oklahoma–Kansas state line | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Sumner | Guelph Township | 4.07 | 6.55 | 4 | ||||

| Avon Township | Southern Terminal toll plaza | |||||||

| 19.21 | 30.92 | 19 | ||||||

| Harmon Township | 26 | 42 | Belle Plaine service area | |||||

| Sumner–Sedgwick county line | Belle Plaine–Salem township line | 33.41 | 53.77 | 33 | ||||

| Sedgwick | Salem Township | 38.31 | 61.65 | 39 | ||||

| Wichita | 43.38 | 69.81 | 42 | |||||

| 45.86 | 73.80 | 45 | ||||||

| 51.21 | 82.41 | 50 | ||||||

| 53.80 | 86.58 | 53 | ||||||

| Butler | Bruno Township | 57 | Andover | |||||

| Towanda Township | 65 | 105 | Towanda service area | |||||

| El Dorado | 71.71 | 115.41 | 71 | |||||

| 76.72 | 123.47 | 76 | ||||||

| Cassoday | 93.45 | 150.39 | 92 | |||||

| Chase | Matfield Township | 97 | 156 | Matfield Green service area | ||||

| Lyon | Emporia | 127.89 | 205.82 | 127 | Northern terminus of I-35 concurrency, Turnpike continues on I-335 | |||

| Fremont Township | 132 | 212 | Emporia service area | |||||

| Waterloo Township | 148.00 | 238.18 | 147 | |||||

| Wabaunsee |

No major junctions | |||||||

| Osage |

No major junctions | |||||||

| Shawnee | Topeka | 178.09 | 286.61 | 177 | I-335 ends and Turnpike continues east on I-470 | |||

| 182.95 | 294.43 | 182 183 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance: eastern terminus of I-470; Turnpike continues east on I-70; signed as exit 182 eastbound and exit 183 westbound | |||||

| Tecumseh Township | 188 | 303 | Topeka service area | |||||

| Douglas | Kanwaka Township | 198.51 | 319.47 | 197 | ||||

| Lawrence | 203.14 | 326.92 | 202 | |||||

| 204.47 | 329.06 | 204 | ||||||

| Leavenworth | Reno Township | 209 | 336 | Lawrence service area | ||||

| 212 | Tonganoxie, Eudora | |||||||

| Stranger Township | Eastern Terminal toll plaza | |||||||

| Wyandotte | Bonner Springs | 225.11 | 362.28 | 224 | Western terminus of US-24 / US-40 concurrency | |||

| Kansas City | 410 | 110th Street | ||||||

| 229.03 | 368.59 | 411 | Signed as exits 411A (south) and 411B (north) | |||||

| 414 | 78th Street | |||||||

| 232.94 | 374.88 | 415 | Turner Diagonal, College Parkway | Signed as exits 415A (Turner Diagonal) and 415B (College Parkway) eastbound | ||||

| 234.47 | 377.34 | 417 | 57th Street | |||||

| 236.08 | 379.93 | 418 | Signed as exits 418A (north) and 418B (south) eastbound; westbound exit is part of exit 419 | |||||

| 236.59 | 380.75 | 419 | Park Drive, 38th Street | |||||

| 237.88 | 382.83 | 420 | Signed as exits 420A (US 69) and 420B (18th Street north); east end of Kansas Turnpike; west end of US-69 overlap | |||||

| 237.98 | 382.99 | |||||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||||

See also

Kansas portal

Kansas portal U.S. Roads portal

U.S. Roads portal

Footnotes

- ↑ The National Bridge Inventory lists the bridge at the state line (CO RD 3604C) as 1958, which matches the other two bridges in Oklahoma north of U.S. Route 177, while the nearby bridges in Kansas are all from 1956. The bridges at and immediately south of US 177 are from 1959.[13]

- ↑ The 1958 Oklahoma State Highway Map, the first to show the turnpike, shows the freeway ending at US 177.[17] The 1959 map is the first to place an I-35 shield on the road.[18]

References

- 1 2 Kansas Turnpike Authority. "History of the Kansas Turnpike". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads (1939). Proposed Interregional Highway System (Map). Scale not given. Washington, DC: Bureau of Public Roads – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads (c. 1943). Routes of the Recommended Interregional Highway System (Map). Scale not given. Washington, DC: Bureau of Public Roads – via Wikimedia Commons.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Lamb, Sherry & Wilson, Theodore A. (1986). Milestones: A History of the Kansas Highway Commission and the Department of Transportation. Topeka: Kansas Department of Transportation. pp. 4–19 to 4–26. OCLC 19126368.

- 1 2 3 Kansas Turnpike Authority (2006). "Chapter 1: The Birth of the Pike" (PDF). Driven by Vision: The Story of the Kansas Turnpike. Wichita: Kansas Turnpike Authority. pp. 4–7. OCLC 147983227.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority (1955). Third Annual Report. Kansas Turnpike Authority. p. 8. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- 1 2 3 United States nominal Gross Domestic Product per capita figures follow the Measuring Worth series supplied in Johnston, Louis & Williamson, Samuel H. (2016). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 10, 2016. These figures follow the figures as of 2015.

- ↑ "Big Impact Seen for Local Area in Superhighway". Lawrence Daily Journal-World. October 24, 1956. pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 3 4 Kansas Turnpike Authority (2006). "Chapter 2: A Vision Builds" (PDF). Driven by Vision: The Story of the Kansas Turnpike. Wichita: Kansas Turnpike Authority. pp. 8–16. OCLC 147983227. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ↑ "KTA Officials Say Traffic Heavy on Pike This Morning". Lawrence Daily Journal-World. October 20, 1956.

- ↑ "Over 12,000 Cars on Turnpike for Special Opening Saturday". Lawrence Daily Journal-World. October 22, 1956.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Kansas Turnpike Authority Frequently Asked Questions". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Federal Highway Administration (1992). "Kansas". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Cover photo". Life. June 4, 1956. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Kansas Turnpike Authority (2006). "Chapter 3: The Early Years, Bumps and All" (PDF). Driven by Vision: The Story of the Kansas Turnpike. Wichita: Kansas Turnpike Authority. pp. 17–24. OCLC 147983227. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- 1 2 Kansas Turnpike Authority (2006). "Chapter 4: The Road Grows Smoother" (PDF). Driven by Vision: The Story of the Kansas Turnpike. Wichita: Kansas Turnpike Authority. OCLC 147983227.

- ↑ Oklahoma Department of Highways (1958). Oklahoma State Highway Map (PDF) (Map) (1958 ed.). Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Highways. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Oklahoma Department of Highways (1959). Oklahoma State Highway Map (PDF) (Map) (1959 ed.). Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Highways. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- 1 2 Kansas Turnpike Authority (2006). "Chapter 5: Rolling toward Tomorrow" (PDF). Driven by Vision: The Story of the Kansas Turnpike. Wichita: Kansas Turnpike Authority. pp. 33–39. OCLC 147983227. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ↑ Buselt, Lori O'Toole (April 7, 2002). "Blaze Guts Rest Stop: A Water Shortage Severely Hampers Fire Crews' Efforts to Battle the Fire at the Belle Plaine Service Area". Wichita Eagle. p. 1B.

- ↑ Abejo, Jerry (April 8, 2002). "Charred Rest Stop Tries to Regroup: Wellington's Fire Chief Says a Water Shortage Had No Effect on the Way the Blaze on the Kansas Turnpike Was Fought". Wichita Eagle. p. 1B.

- 1 2 Strongin, Dana (July 24, 2003). "Rebuilt Center Greets Visitors: Fifteen Months After a Grease Fire Caused More than $2 Million in Damage, the Belle Plaine Service Area Reopens—New and Improved". Wichita Eagle. p. 1B.

- ↑ Mann, Fred; McMillin, Molly (September 1, 2003). "Turnpike Flood Kills 4". Wichita Eagle. p. 1A.

- ↑ Hays, Jean (September 11, 2003). "Concrete Barriers Helped Dam I-35". Wichita Eagle. p. 1A.

- 1 2 Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Toll Schedule" (PDF). Kansas Turnpike Authority. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Self-Pay Lanes". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "K-Tag". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Retrieved February 28, 2008.

- ↑ Franke, Susan (February 3, 2002). "Toll Tags Apeed Traffic Through Booths and Maybe Drive-Through Lanes, Too". Kansas City Business Journal. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority (KTA pamphlet).

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Recent Developments & Turnpike News (September–October 2009)". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ↑ King, Mike (March 28, 2014). "Simplifying Travel: A Partnership between Kansas & Oklahoma". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Begley, Dug (June 19, 2016). "Local Toll Tags Going National, Eventually". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Google (November 19, 2012). "Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ↑ Champlin Refining Company; Rand McNally (1973). Kansas–Nebraska (Map). Champlin Refining Company.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kansas Department of Transportation (2013). Official State Transportation Map (PDF) (Map) (2013–14 ed.). Topeka: Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1976). "5 km E of South Haven, Kansas, United States" (Topographic map). Microsoft Research Maps. Microsoft. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ↑ State Highway Commission of Kansas, Department of Planning and Development (1968). General Highway Map: Sumner County, Kansas (PDF) (Map). Topeka: State Highway Commission of Kansas. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1981). "6 km E of Wellington, Kansas, United States" (Topographic map). Microsoft Research Maps. Microsoft. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (March 20, 1996). "5 km E of Wellington, Kansas, United States" (Aerial photograph). Microsoft Research Maps. Microsoft. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500961383". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kansas Turnpike Authority. "KTA Services". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Kansas Department of Transportation. "KDOT Interchange Sketches". Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500961343". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Exit 33 Mulvane Interchange". Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500874323". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1982). Derby, KS (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-607-00659-9.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999913500872333". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ State Highway Commission of Kansas, Highway Planning Department (1960). General Highway Map: Sedgwick County, Kansas (PDF) (Map). Topeka: State Highway Commission of Kansas. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500872433". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500872563". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500873573". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500081523". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1979). El Dorado SW, KS (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-607-20603-6.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500080913". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500081543". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Kansas Department of Transportation (2013). Official State Transportation Map (PDF) (Map) (2013–14 ed.). Topeka: Kansas Department of Transportation. Physiographic Provinces inset. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1967). Cassoday, KS (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ State Highway Commission of Kansas, Highway Planning Department (1964). General Highway Map: Butler County (PDF) (Map). Topeka: State Highway Commission of Kansas. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999903500081623". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Google (June 16, 2013). "Kansas Turnpike: Distance from Matfield Green Services to Cattle Pens" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1979). Emporia, KS (Topographic map). 1:24:000. 7.5 Minute. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Construction Updates". Kansas Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ↑ Adderly, Kevin (January 27, 2016). "Table 2: Auxiliary Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as of December 31, 2015". Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Kansans Can Drive at 65 on 680 Miles". Lawrence Journal-World. Associated Press. May 14, 1987. p. 1A. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (2012). "NBI Structure Number: 999933500561053". National Bridge Inventory. Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ Google (March 25, 2013). "Overview of Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ↑ Kansas Department of Transportation (2013). Kansas Official State Transportation Map (PDF) (Map) (2013–14 ed.). Topeka: Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "K-10 Closed Friday, May 12 Due to Cycling Race" (Press release). Kansas Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1991). Lawrence West, KS (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-607-20953-2.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1978). Lawrence East, KS (Topographic map). 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute. Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-607-20952-5.

- ↑ Google (June 13, 2013). "Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority (February 24, 2006). "KTA to Build New Interchange near Tonganoxie" (Press release). Kansas Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey (July 1, 1988). "Kansas City, Missouri, United States" (Topographic map). Microsoft Research Maps. Microsoft. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ↑ Google (June 13, 2013). "Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ Google (June 13, 2013). "Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ Google (June 13, 2013). "Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ Google (June 13, 2013). "Kansas Turnpike" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kansas Turnpike Authority. "The Story of the Kansas Turnpike" (SWF). Kansas Turnpike Authority. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ↑ Rand McNally (2010). United States–Canada–Mexico Road Atlas (Map). Chicago: Rand McNally.

- ↑ "New Kansas Turnpike Has No Speed Limit". Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. October 8, 1956. p. 4. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ "When Speed Limits Are Unsafe". Chicago Tribune. August 31, 1970. p. 16. Retrieved April 25, 2011. (subscription required)

- ↑ Cook, Louise (March 4, 1974). "55-Mile Per Hour Speed Limit Takes Effect". Lewiston Morning Journal. Associated Press. p. 7. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Some Turnpike Speed Limits to Rise". The Daily Union. Junction City, KS. Associated Press. April 12, 1987. p. 35. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ "State Works on Turnpike Speed Limit". Lawrence Journal-World. Associated Press. May 26, 1987. p. 9A. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Speed Limit Is Increased to 65 on Turnpike from Topeka to Emporia". The Daily Union. Junction City, KS. Associated Press. October 25, 1987. p. 8. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ Truell, Matt (December 1, 1995). "Governor Delays Speed Limit Increase on State Highways". The Daily Union. Junction City, KS. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ Peterson, John (March 6, 1996). "Graves Signs Bill Raising Speed Limits". Kansas City Star. p. C1. Retrieved April 25, 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Kansas Department of Transportation (June 21, 2011). "Kansas Routes Designated for 75 mph Speed Limit" (PDF) (Press release). Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ↑ Kansas Highway Patrol. "Facts & FAQs: Traffic Violations". Kansas Highway Patrol. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority (Spring 2004). "Rockne Memorial Reopens at Matfield Green Service Area". Turnpike Times. Kansas Turnpike Authority.

- ↑ Kansas Turnpike Authority. "Kansas Turnpike Authority 2003 Annual Report" (PDF). Kansas Turnpike Authority. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ↑ Kansas Department of Transportation (2001). Official State Transportation Map (PDF) (Map) (2001–02 ed.). Topeka: Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Kansas Department of Transportation (2003). Official State Transportation Map (PDF) (Map) (2003–04 ed.). Topeka: Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Federal Highway Administration (September 20, 2012). "National Highway Planning Network" (ESRI shapefile). Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kansas Turnpike. |

- Kansas Turnpike Authority

- Kansas Highway Maps: Current, Historic, KDOT

- Kansas Turnpike Authority Annual Reports (KGI Library)