Lawrence, Kansas

| Lawrence, Kansas | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

Massachusetts Street downtown | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): River City[1] | ||

| Motto: From Ashes to Immortality | ||

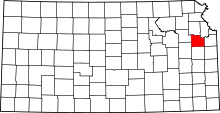

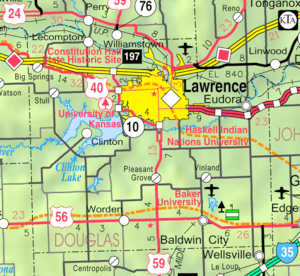

Location within Douglas County and Kansas | ||

KDOT map of Douglas County (legend) | ||

| Coordinates: 38°58′18″N 95°14′7″W / 38.97167°N 95.23528°WCoordinates: 38°58′18″N 95°14′7″W / 38.97167°N 95.23528°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Kansas | |

| County | Douglas | |

| Founded | 1854 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Mike Amyx [2] | |

| • Vice Mayor | Leslie Soden[2] | |

| • City Manager | Tom Markus[3] | |

| Area[4] | ||

| • Total | 34.26 sq mi (88.73 km2) | |

| • Land | 33.56 sq mi (86.92 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.70 sq mi (1.81 km2) | |

| Elevation[5] | 866 ft (264 m) | |

| Population (2010)[6] | ||

| • Total | 87,643 | |

| • Estimate (2015)[7] | 93,917 | |

| • Density | 2,600/sq mi (990/km2) | |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) | |

| ZIP code | 66044-66047, 66049 | |

| Area code | 785 | |

| FIPS code | 20-38900 [5] | |

| GNIS ID | 0479145 [5] | |

| Website |

lawrenceks | |

Lawrence is the sixth largest city in the state of Kansas and the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas. It is located in northeastern Kansas next to Interstate 70, along the banks of the Kansas and Wakarusa Rivers. As of the 2010 census, the city's population was 87,643.[8] Lawrence is a college town and is the home to the University of Kansas and Haskell Indian Nations University.

Lawrence was founded by the New England Emigrant Aid Company and was named for Amos Adams Lawrence who offered financial aid and support for the settlement.[9][10] Lawrence was central to the Bleeding Kansas era and was the site of the Wakarusa War, the sacking of Lawrence, and the Lawrence Massacre.[11]

Lawrence had its beginnings as a center of Kansas politics. However, its economy soon diversified into many industries including agriculture, manufacturing, and ultimately education, beginning with the founding of the University of Kansas in 1866, and later Haskell Indian Nations University in 1884.

History

Settlement

Prior to Kansas Territory being opened to settlement in May 1854, most of Douglas County was part of the Shawnee Indian Reservation.[12] The Oregon Trail followed the Kansas River through what would become Lawrence and Mount Oread was used as a landmark and an outlook.[12]

Dr. Charles Robinson and Charles Branscomb were sent by the New England Emigrant Aid Company to scout for a location for a city. They arrived in the vicinity of Lawrence in July 1854 and noted the beauty of the area and felt the area was well suited for a town.[12]

The original “pioneer party” left Massachusetts on July 17, 1854 and consisted of 29 men.[12] They arrived at the site Robinson and Branscomb selected on August 1. The second party arrived in Lawrence on September 9 after leaving August 9.[12] The town was officially named Lawrence City on October 6. Original names for the settlement were Wakarusa, Yankee Town, New Boston[12] and Plymouth but Lawrence was chosen to honor Amos A. Lawrence, a valuable benefactor of the Emigrant Aid Company and because “the name sounded well and had no bad odor attached to it in any part of the Union."[12] The main street of the town was named Massachusetts to commemorate the origins of the pioneer party.[13]

The first post office in Lawrence was established in January 1855.[14]

In March 1857, the Quincy School was started in the Emigrant Aid office before moving to the basement of the Unitarian Church in April. The Plymouth Congregational Church was started in September 1854 by Reverend S.Y. Lum, a missionary sent to Kansas.

Bleeding Kansas and the Civil War

Shortly after Lawrence’s founding, two newspapers were started: The Kansas Pioneer and the Herald of Freedom. Both papers touted the Free State mission which caused problems from the people of Lecompton, then the pro-slavery headquarters, located about ten miles northwest of Lawrence, and land squatters from Missouri. The Kansas Free State began in early January 1855.[15]

On November 21, 1855, Charles Dow was shot and killed by Franklin Coleman in Hickory Point about fourteen miles south of Lawrence. Shortly after, a small army of Missourians led by Douglas County Sheriff Samuel L. Jones entered Kansas to attack Lawrence. John Brown and James Lane had hustled Lawrence citizens into an army and erected barricades but no attack happened. A treaty was signed and the Missouri army reluctantly left.[16]

Harassment by Sheriff Jones and other Southern sympathizers continued unabated. The Herald of Freedom, the Kansas Free State and the Free State Hotel were indicted as being “nuisances.”[15] On April 23, 1856 Sheriff Jones was shot while trying to arrest free-state settlers.[17] On May 21, Sheriff Jones and a posse of 800 Southern sympathizers converged on Lawrence. Dr. Robinson’s house on Mount Oread was taken by the federal marshal as headquarters and the newspaper printing presses were damaged and thrown in the river. The Free State Hotel was also destroyed.[18]

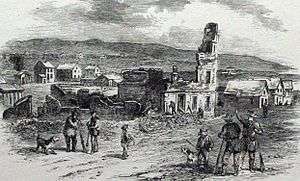

Despite the constant presence of impending war, Lawrence continued to grow. Its 1860 population was estimated at 2,500 although the official Census recorded 1,645.[19] Lawrence became the county seat of Douglas County in 1857, prior to that Lecompton had been the seat and even when the American Civil War broke out in April 1861, Lawrence was still a magnet to conflict. William Clarke Quantrill and 300-400 Confederate guerillas rode into Lawrence and sacked the city at dawn on August 21, 1863. Most houses and businesses in Lawrence were burned and between 150 and 200 men and boys were murdered.[20][21]

Post-Civil War

_(cropped).jpg)

Attempts to begin a university in Kansas were first undertaken in 1855,[22] but it was only after Kansas became a state in 1861 that those attempts saw any real fruition. An institute of learning was proposed in 1859 as The University of Lawrence, but it never opened. When Kansas became a state, provision was included in the Kansas Constitution for a state university.[22] From 1861 to 1863 the question of where the university would be located—Lawrence, Manhattan or Emporia—was debated. In February 1863, Manhattan was made the location of the state's land-grant college, leaving only Lawrence and Emporia as candidates. The fact that Lawrence had $10,000 plus interest donated by Amos Lawrence plus 40 acres (160,000 m2) to donate for the university had great weight with the legislature and Lawrence beat out Emporia by one vote. The University of Kansas officially opened in 1866 with 55 students.[22]

_(cropped).jpg)

Facing an energy crisis in the early 1870s, the city contracted with Orlando Darling to construct a dam across the Kansas River to help provide the city with power. Frustrated with the construction of the dam, Darling resigned and the Lawrence Land & Water Company completed the dam without him in 1873; however, only when J.D. Bowersock took over the dam in 1879 that the constant damage to the dam ceased and repairs held up. The dam made Lawrence unique which helped in winning business against Kansas City and Leavenworth. The dam closed in 1968 but was reopened in 1977 with help from the city, which wanted to build a new city hall adjacent to the Bowersock Plant.[23][24]

In 1884 the United States Indian Industrial Training School was opened in Lawrence. Boys were taught the trades of tailor making, blacksmithing, farming and others while girls were taught cooking and homemaking. In 1887 the name was changed to the Haskell Institute, after Dudley Haskell, a legislator responsible for the school being in Lawrence. In 1993 the name was changed again to Haskell Indian Nations University.[25]

North Lawrence

Grant Township, north of the Kansas River, was annexed to Douglas County in 1870 from southern Sarcoxie Township in Jefferson County. The largest city in the township was Jefferson, founded in 1866 just over the river from Lawrence. Jefferson was renamed North Lawrence in 1869 and it was attempted to annex the town to Lawrence proper but the motion failed. In 1870 the State Legislature annexed the town.[26]

Just northeast of North Lawrence was the site of Bismarck Grove, home to numerous picnics, temperance meetings and fairs. In 1870, "Bismarck" was organized and the first gathering was a temperance meeting in 1878. The last fair was held at the Grove in 1899 and the area became private property in 1900.[27]

20th century and beyond

In 1888, Watkins National Bank opened at 11th and Massachusetts. Founded by Jabez B. Watkins, the bank would last until 1929. Watkin’s wife Elizabeth donated the bank building to the city to use as a city hall. In 1970, the city built a new city hall and after extensive renovations, the bank reopened in 1975 as the Elizabeth M. Watkins Community Museum.[28]

In 1903, the Kansas River flooded causing property damage in Lawrence, especially North Lawrence. The water got as high as 27 feet and water marks can still be seen on some buildings especially at TeePee Junction at the U.S. 24-40 intersection and at Burcham Park.[29][30] Lawrence would be hit by other floods in 1951,[31] where the water rose over 30 feet,[30] and in 1993 but with the reservoir and levee system in place, Lawrence only had minimal damage compared to the other floods.[32]

Also in 1903, Theodore Roosevelt visited Lawrence on his way to Manhattan where he gave a short speech and dedicated a fountain at 9th & New Hampshire.[33] The fountain was later moved to South Park next to the gazebo. Roosevelt would visit Lawrence again in 1910 after visiting Osawatomie where he dedicated the John Brown State Historical Site and gave a speech on New Nationalism.[34]

In 1871, the Lawrence Street Railway Company opened and offered citizens easy access to hotels and businesses along Massachusetts Street. The first streetcar was pulled by horses and mules and the track just ran along Massachusetts Street. After the 1903 flood, the Kansas River bridge had to be rebuilt but was not considered safe for a streetcar to pass over. The Lawrence Street Railway Company closed later that year. In 1907, C.L. Rutter attempted to bring back a bus system, after having failed in 1902. In 1909, a new streetcar system was implemented putting Rutter out of business and lasting until 1935.[35]

In 1921, Lawrence Memorial Hospital opened in the 300 block of Maine Street. It started with only 50 beds but by 1980, the hospital would expand to 200.[36] LMH has been awarded several awards and recognitions for care and quality including The Hospital Value Index Best in Value Award and is ranked nationally in the top five percent for heart attack care by the American College of Cardiology.[37]

In 1929 Lawrence began celebrating its 75th anniversary. The city dedicated Founder’s Rock, commonly referred to as the Shunganunga Boulder, a huge red boulder brought to Lawrence from near Tecumseh. The rock honors the two parties of the Emigrant Aid Society who first settled in Lawrence.[38] Lawrence also dedicated the Lawrence Municipal Airport on October 14.[30]

In 1943, the federal government transported German and Italian prisoners of World War II to Kansas and other Midwest states to work on farms and help solve the labor shortage caused by American men serving in the war effort. Large internment camps were established in Kansas: Camp Concordia, Camp Funston (at Fort Riley), Camp Phillips (at Salina under Fort Riley). Fort Riley established 12 smaller branch camps, including Lawrence.[39] The camp in Lawrence was near 11th & Haskell Avenue near the railroad tracks. The camp would close by the end of 1945.

In 1947, Gilbert Francis and his son George opened Francis Sporting Goods downtown, selling mostly fishing and hunting gear. A decade later they moved across the street to larger retail space at 731 Massachusetts Street, enabling them to expand into other sporting goods. In November 2014, in the wake of the opening of a new Dick's Sporting Goods location in Lawrence, Francis Sporting Goods, announced its retail business, located within what had become Lawrence's Downtown Historic District, would be closed by the end of the year, allowing the Francis family to focus on supplying uniforms and equipment to teams.[40]

In the early 1980s, Lawrence grabbed attention from the television movie The Day After. The TV movie first appeared on ABC but was later shown in movie theaters around the world. The movie depicted what would happen if the United States were destroyed in a nuclear war. The movie was filmed in Lawrence, and hundreds of local residents appeared in the film as extras and in speaking roles.[41]

In 1989, the Free State Brewing Company opened in Lawrence becoming the first legal brewery in Kansas in more than 100 years.[42] The restaurant is in a renovated inter-urban trolley station in downtown Lawrence.

In 2007, Lawrence was named one of the best places to retire by U.S. News & World Report.[43] In 2011, the city was named one of America's 10 best college towns by Parents & Colleges.[44]

Geography

Downtown Lawrence is located at 38°58′18″N 95°14′7″W / 38.97167°N 95.23528°W (38.959902, −95.253199), approximately 25 miles (40 kilometers) east of Topeka, and 35 mi (56 km) west of Kansas City, Kansas. Though Lawrenece has a desigated elevation of 866 feet (264 m),[45] the highest elevation is Mount Oread on the University of Kansas campus with an elevation of 1,020 feet (310 m).[46][47]

The city lies on the southern edge of the Dissected Till Plains, bordering the Osage Plains to the south.[48][49] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 34.26 square miles (88.73 km2), of which, 33.56 square miles (86.92 km2) is land and 0.70 square miles (1.81 km2) is water,[4] and is split between Wakarusa Township and Grant Township with small portions in Lecompton, Kanwaka and Clinton Townships.

Lawrence is located between the Kansas and Wakarusa rivers. There are several major creeks that flow through Lawrence. Burroughs Creek in east Lawrence and Baldwin Creek in northwestern Lawrence that converge with the Kansas River. Yankee Tank Creek in southwest Lawrence and an unnamed creek that flows through central Lawrence converge with the Wakarusa River south of the city. Yankee Tank Creek is dammed to form Lake Alvamar, which was originally called Yankee Tank Lake.[50] The Wakarusa River is dammed to form Clinton Lake. Potter Lake is located on KU Campus and Mary’s Lake is located in southeastern Lawrence as part of Prairie Park. There are also the Haskell-Baker Wetlands maintained by Haskell University and Baker University.[51]

Lawrence has 54 parks which includes community parks, neighborhood parks, trails, cemeteries and nature preserves.[52] Community parks include South Park, Buford Watson Park, Broken Arrow Park, Riverfront Park, Holcomb Park, “Dad” Perry Park, Centennial Park and Prairie Park. Cemeteries include Oak Hill, Maple Grove and Memorial Park.[53] The first cemetery in Lawrence, Pioneer Cemetery, is on the University of Kansas campus and is maintained by KU.

Climate

Lawrence has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), typically experiencing hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters.[54] The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 28.4 °F (−2.0 °C) in January to 78.5 °F (25.8 °C) in July. The high temperature reaches or exceeds 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 32 days a year and 100 °F (38 °C) an average of 1.9 days. The minimum temperature falls to or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on an average 4.9 days a year.[55] Extreme temperatures range from 111 °F (44 °C) on July 13 and 14, 1954 down to −21 °F (−29 °C) on December 22, 1989.[56]

On average, Lawrence receives 39.9 inches (1,010 mm) of precipitation annually, most of which occurs in the warmer months, and records 96 days of measurable precipitation.[55] Measurable snowfall occurs an average of 8 days per year with 4.6 days receiving at least 1.0 inch (2.5 cm). Snow depth of at least one inch occurs an average of 15.8 days a year.

| Climate data for Lawrence, Kansas (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

82 (28) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

107 (42) |

111 (44) |

107 (42) |

108 (42) |

98 (37) |

84 (29) |

76 (24) |

111 (44) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38.5 (3.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

54.8 (12.7) |

64.6 (18.1) |

74.4 (23.6) |

83.4 (28.6) |

88.6 (31.4) |

87.8 (31) |

79.0 (26.1) |

67.5 (19.7) |

53.8 (12.1) |

40.6 (4.8) |

64.8 (18.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.3 (−7.6) |

22.0 (−5.6) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

54.1 (12.3) |

63.5 (17.5) |

68.4 (20.2) |

66.2 (19) |

56.9 (13.8) |

45.4 (7.4) |

32.7 (0.4) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

43.6 (6.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −18 (−28) |

−11 (−24) |

−7 (−22) |

13 (−11) |

30 (−1) |

44 (7) |

51 (11) |

42 (6) |

31 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

2 (−17) |

−21 (−29) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.98 (24.9) |

1.36 (34.5) |

2.71 (68.8) |

4.06 (103.1) |

5.36 (136.1) |

5.88 (149.4) |

4.14 (105.2) |

4.05 (102.9) |

4.20 (106.7) |

3.35 (85.1) |

2.20 (55.9) |

1.60 (40.6) |

39.89 (1,013.2) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.8 (9.7) |

4.3 (10.9) |

0.8 (2) |

0.2 (0.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.5) |

0.9 (2.3) |

3.2 (8.1) |

13.4 (34) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.2 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 96.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 8.0 |

| Source: NOAA[55] The Weather Channel[56] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Streets

Originally, north–south streets were named after the states in the order they were admitted to the union and east–west streets were named after people involved in the American Revolution. Massachusetts was selected for the main thoroughfare since the original settlers came from Massachusetts. Over the years, however, this plan became marred causing Oregon Street to be placed before Delaware, North and South Carolina being represented by a single Carolina Street near Lawrence High School and nine states not being included, as a few examples.[9] The state street naming was abandoned with Iowa Street, which runs through the center of Lawrence. In 1913, east-west streets, originally named for important people of the American Revolution, were renamed to numbered streets.[57]

Lawrence is split between east and west by Massachusetts Street and separated north and south by an imaginary line a block north of 2nd Street. North–south streets in North Lawrence are numbered from North 1st Street to North 9th Street, while east–west streets in Lawrence are numbered from 2nd Street to 34th Street.

Neighborhoods

Lawrence is designated by neighborhoods. Neighborhoods closest to Downtown are Old West Lawrence, East Lawrence, Oread, Hancock and Pinckney. The first neighborhood west of Iowa Street was Sunset Hills. There are several neighborhoods listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Old West Lawrence,[58] Oread,[59] Hancock,[60] Breezedale,[61] and most of Rhode Island Street[62][63] in East Lawrence.

Architecture

The architecture of Lawrence is greatly varied. Most buildings built before 1860 were destroyed in the Lawrence Massacre. Architectural styles represented in Old West Lawrence are Italianate, Victorian, Gothic Revival, Tudor, Richardson Romanesque and many others.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,645 | — | |

| 1870 | 8,320 | 405.8% | |

| 1880 | 8,510 | 2.3% | |

| 1890 | 9,997 | 17.5% | |

| 1900 | 10,862 | 8.7% | |

| 1910 | 12,374 | 13.9% | |

| 1920 | 12,456 | 0.7% | |

| 1930 | 13,726 | 10.2% | |

| 1940 | 14,390 | 4.8% | |

| 1950 | 23,351 | 62.3% | |

| 1960 | 32,858 | 40.7% | |

| 1970 | 45,698 | 39.1% | |

| 1980 | 52,738 | 15.4% | |

| 1990 | 65,608 | 24.4% | |

| 2000 | 80,098 | 22.1% | |

| 2010 | 87,643 | 9.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 93,917 | [7] | 7.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[64] | |||

Lawrence is the anchor city of the Lawrence, Kansas Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Douglas County.

2010 census

As of the census of 2010, there were 87,643 people, 34,970 households, and 16,939 families residing in the city.[6] The population density was 2,611.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,008.3/km2). There were 37,502 housing units at an average density of 1,117.5 per square mile (431.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 82.0% White, 4.7% African American, 3.1% Native American, 4.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.5% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.7% of the population.

There were 34,970 households of which 24.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.6% were married couples living together, 8.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 51.6% were non-families. 32.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.91.

In the city the population was spread out with 17.5% of residents under the age of 18; 28.7% of residents between the ages of 18 and 24; 27.4% from 25 to 44; 18.5% from 45 to 64; and 8% were 65 years of age or older. The median age in the city was 26.7 years. The gender makeup of the city was 50.2% male and 49.8% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 80,098 people, 31,388 households, and 15,725 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,849.4 people per square mile (1,100.2/km2). There were 32,761 housing units at an average density of 1,165.4 per square mile (450.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.80% White, 5.09% African American, 2.93% Native American, 3.78% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 1.36% from other races, and 2.97% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.65% of the population. 23.8% were of German, 10.6% English, 10.1% Irish and 7.1% American ancestry according to Census 2000. 91.0% spoke English, 2.9% Spanish and 1.0% Chinese or Mandarin as their first language.

Of the 31,388 households, 25.1% included children under the age of 18, 38.0% were married couples living together, 8.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 49.9% were non-families. 30.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city the population was spread out with 18.6% under the age of 18, 30.7% from 18 to 24, 28.5% from 25 to 44, 15.1% from 45 to 64, and 7.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 25 years. For every 100 females there were 98.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.2 males.

As of 2000 the median income for a household was $34,669, and the median income for a family was $51,545. Males had a median income of $33,481 versus $27,436 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,378. About 7.3% of families and 18.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.6% of those under age 18 and 7.7% of those age 65 or over. However, traditional statistics of income and poverty can be misleading when applied to cities with high student populations, such as Lawrence.[65][66]

Economy

Lawrence has a diverse economy spanning education, industrial, agricultural, government, finance and scientific research, most of these are related to the University of Kansas, which is the largest employer in Lawrence. The largest private employer in Lawrence is General Dynamics.[lower-alpha 1][67] Lawrence Public Schools, the City of Lawrence, Lawrence Memorial Hospital and Hallmark Cards round out the top six employers.[67]

Lawrence saw growth in the industrial sector in the 1980s in part to the development of the East Hills Business Park in 1986.[68] The industrial land opportunities provided by the East Hills Business Park provided space for national companies such as AMARR Garage Doors to house one of their two manufacturing facilities. The new industrial park also provided opportunities for Kansas City-based company's like PROSOCO to move their business operations to Lawrence.[69]

Historic sites and museums

South Park is a large park in Downtown Lawrence divided by Massachusetts Street just south of the county courthouse between North Park and South Park Streets. The park originally consisted of four separate parks—Lafayette, Hamilton, Washington and Franklin Parks—but was combined to form one park.[70] South Park was developed in 1854 as part of the original city plat. A gazebo was built in South Park in 1910 and is used for annual city band performances during the summer months.[70]

The Watkins Museum of History is located a block north of South Park and houses exhibits from Lawrence and Douglas County. The building is managed by the Douglas County Historical Society and used to be Watkins National Bank (1883–1929) and Lawrence City Hall (1929–1970). The third floor of the building was used as a home office and a bathtub and sink are still in place.[28] Next door to the museum is a Japanese Friendship Garden designed by the city and representatives from sister city Hiratsuka, Japan. An exhibit on the Bleeding Kansas era and the Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Area is located in the old Lawrence Public Library at 9th and Vermont Streets. Other museums are located on KU campus including the Natural History Museum in Dyche Hall, the Spencer Museum of Art and the Dole Institute of Politics among others.

Centennial Park, located between 6th and 9th Streets and Rockledge Road and Iowa Street, was established in 1954 for the city's 100th anniversary. The park features rolling hills, a skatepark, a disc golf course and a Polaris missile constructed during the Cold War.[71] Sesquicentennial Park is located near Clinton Lake and was established for Lawrence's 150th anniversary and is mostly undeveloped but features a timeline of Lawrence history and a time capsule to be opened in 2054.[72]

Liberty Hall was built when the Bowersock Opera House burned down in 1911.[73] Liberty Hall is a small theater typically showcasing independent movies and the occasional live act. Liberty Hall also runs a video rental next door.[74] The Granada Theater was originally built in 1928 as a vaudeville theater. It was renovated in 1934 as a movie theater until closing in 1989. It was renovated again in 1993 and opened as a venue for comedy acts and live music.

The Eldridge Hotel was first built in 1855 as the Free State Hotel by Colonel Shalor Eldridge. The hotel was destroyed during the sack of Lawrence. Col. Eldridge rebuilt the Free State and added an extra story, vowing to do so every time. The Free State was destroyed again during Quantrill's Raid but Eldridge rebuilt again and renamed the hotel The Eldridge. In 1925, due to deterioration, the Eldridge was demolished and rebuilt but was closed and converted into apartments in 1970. In 1985, work began to renovate the Eldridge back into a hotel and in 2004 the building was sold and completely renovated back to its 1925 look.[75] It is rumored that the ghost of Colonel Shalor Eldridge haunts the Eldridge and was featured on the Biography Channel's series My Ghost Story.[76]

Memorial Stadium and Allen Fieldhouse are located on KU campus. Memorial Stadium was built in 1920 for the Kansas Jayhawks football program. It was named to honor KU students who died in World War I. Allen Fieldhouse was built in 1955 for the basketball program and was named for Phog Allen, a coach at KU from 1907 to 1909 and 1919 to 1956. On November 4, 2010, the ESPN's online publication, The Magazine, named Allen Fieldhouse the loudest college basketball arena in the country,[77] whilst prominent sportswriter, Mark Whicker, has publicly declared that the fieldhouse is "the best place in America to watch college basketball."[78]

Oak Hill Cemetery in east Lawrence was established in 1866 and was called by William Allen White the "Kansas Arlington."[79] The cemetery features the burials of James Lane, Lucy Hobbs Taylor, Langston Hughes' grandparents, numerous veterans and many prominent Kansans.[79] Across the street is Memorial Park Cemetery which features a memorial for KU coach and inventor of basketball James Naismith. The memorial is a cenotaph but Naismith is buried in the mason section of Memorial Park.[80]

Lawrence is also the site of many historic houses related to the history of the city. The Robert Miller house survived Quantrill's Raid and was a stop on the Underground Railroad,[81] Ferdinand Fuller, an original settler of Lawrence, built his house atop of Windmill Hill in what is now the Hillcrest Neighborhood[82] and the John Roberts House, commonly called the Castle Tea Room, was designed by famed architect John G. Haskell in 1894 and is now used for various formal events.[83][84] There are many other houses of historic prominence in Lawrence, many of them on the National Register of Historic Places.

Arts and culture

The city is known for a thriving music and art scene. Rolling Stone named Lawrence one of the "best lil' college towns" in the country in its August 11, 2005, issue.[85] The New York Times said Lawrence had "the most vital music scene between Chicago and Denver" in a travel column on February 25, 2005.[86] Locally owned bar and music venue The Replay Lounge was named one of Esquire magazine's top 25 bars/venues in the country in 2007.[87]

In December 2005, the city announced International Dadaism Month, celebrating the early 20th century art movement. In the spirit of Dada, rather than select a typical calendar month for the occasion, Highberger set the dates for the "Month" as February 4, March 28, April 1, July 15, August 2, August 7, August 16, August 26, September 18, September 22, October 1, October 17, and October 26, determined by rolling dice and pulling numbers out of a hat.[88][89]

Lawrence is home to many bands and record labels. Many artists, such as Mansion, Mates of State, The New Amsterdams, Kansas, Fourth of July, White Flight, The Anniversary, Minus Story, The Appleseed Cast, La Guerre, Old Canes, Ad Astra Per Aspera, Ghosty, The Esoteric and The Get Up Kids originated in Lawrence or its surrounding areas. KJHK 90.7 FM, the University of Kansas's student-run radio station, is a staple of the local music scene. It won a CMJ award in 2006 for "most improved station" and was nominated for a Plug Award for best college radio station in 2007.

The Wakarusa Music and Camping Festival was a four-day-long weekend music festival held annually in early June just outside Lawrence, at Clinton State Park. After its inception in 2004, the festival had grown dramatically by 2006, with almost 60,000 tickets sold, while developing a nationwide following that accounted for 80% of ticket sales. The festival featured an eclectic mix of music, with artists like The Flaming Lips, Wilco, STS9, Medeski, Martin and Wood, Neko Case, and Widespread Panic taking the stage. The event is kept smaller than other festivals such as Bonnaroo by an agreement with the state.[90] Activities other than music include disc golf, yoga, hiking, and swimming in Clinton Lake. The festival was relocated to Mulberry Mountain due to a dispute between the organizers and the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks over limiting attendees and over rent payment.[91]

Sports

Lawrence is also the home of the University of Kansas athletic teams. The perennially highly ranked (1922, 1923, 1952, 1988, 2008 NCAA Champions) Kansas Jayhawks basketball team is closely followed by most residents during the winter. Massachusetts Street, the primary street of downtown Lawrence, flooded with fans in 2002, 2003, 2008, and 2012 after both KU's victories and defeats in the final rounds of the NCAA tournaments those years. KU's football team had their best record in their school history in 2007 going 12-1 and culminating with a victory in the Orange Bowl. The city honored the university's mascot, the Jayhawk, in 2003 when 30 statues of Jayhawks were commissioned by the Lawrence Convention and Visitors Bureau; these can be seen throughout the city as part of an art installation called "Jayhawks on Parade." The Jayhawks also field a soccer team, baseball and softball teams, track and field teams, cross country teams, and a men's hockey team. KU also has a Rugby team. It is run by the KU Rugby Football club, with a clubhouse in North Johnny's Tavern. They run the high school and the club team as well.

Government

Lawrence is run by a city commission and city manager. Commissioners consists of five individuals elected by the citizens. Three commissioner seats are up for reelection every two years. The two top vote-getters receive a four-year term, third-place finisher receives a two-year term. The commission elects a mayor and vice-mayor every year in April, usually the two top vote-getters, and also hires the city manager.[92]

While Kansas is a heavily Republican state, Lawrence since the late 20th century has tended to lean towards the Democrat party.[93] Douglas County, where Lawrence is situated, was one of only two counties in Kansas whose majority voted for John Kerry in the 2004 presidential election and one of only three that voted for Barack Obama in the 2008 election. Douglas County has supported the Democratic candidate the past six presidential elections.[94][95][96][97][98][99] Currently, Lawrence is served by Republican state representative Tom Sloan and Democratic state representatives John Wilson, Barbara Ballard and Dennis "Boog" Highberger; state senators Marci Francisco, Tom Holland and Anthony Hensley, all Democrats. Lawrence is represented federally by Republican Lynn Jenkins of the 2nd and U.S. Senators Pat Roberts and Jerry Moran, both Republicans. Prior to 2002, Lawrence sat entirely within the 3rd district until reapportionment which split Lawrence between the 2nd and 3rd districts until 2012 when Lawrence was placed entirely within the 2nd.[100]

Lawrence was the first city in Kansas to enact an ordinance (enacted in 1995, after a campaign called Simply Equal) prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. On October 4, 2011, Lawrence became the first city in Kansas to prohibit discrimination based on gender identity, the effort to pass the GIO was led by Scott Criqui from the Kansas Equality Coalition. Scott Criqui would go on to become the first openly gay candidate to run for office and win an election in Lawrence, KS. Douglas County is the only county in the state to reject the amendment to the Kansas Constitution prohibiting both gay marriage and civil unions in April 2005. The vote against the amendment was primarily in the city of Lawrence; outside the city, the amendment carried in the rest of Douglas County. Lawrence has an active chapter of the Kansas Equality Coalition, which persuaded the city commission to approve a domestic partner registry on May 22, 2007. The registry, which took effect on August 1, 2007, provides unmarried couples—both same-sex and other-sex—some recognition by the city for legal purposes.[101]

Education

Primary and secondary education

The Unified School District 497 includes fourteen public grade schools, four middle schools: Liberty Memorial Central, West, South, and Southwest, and two high schools: Lawrence High School and Lawrence Free State High School.[102] The athletic teams of the former are nicknamed the Chesty Lions, and those of the latter are the Firebirds. Both schools are Class 6A in enrollment size, and Lawrence High School leads the State of Kansas in most state championships won, with 107 championships. The Lawrence High School football team also leads the nation with most undefeated seasons at 31, though all of these occurred before Free State High School came into existence. Private high schools include Bishop Seabury Academy, which is affiliated with the Episcopal Church, and the interdenominational Veritas Christian School. There is also St. John Catholic School, which teaches grades Pre-K through eight and is funded by the Catholic communities of Lawrence and Corpus Christi Catholic School. Raintree Montessori School is a secular private school which teaches preschool through grade six. The Prairie Moon School is a Waldorf school near Lawrence. The city has 15 public schools: Langston Hughes Elementary, which is named after Langston Hughes; Quail Run Elementary, Broken Arrow Elementary, Cordley Elementary, Hillcrest Elementary, Kennedy (pre-K-6), Pinckney Elementary, Prairie Park Elementary, New York Elementary, Schwelger Elementary, Sunflower Elementary, Sunset Hill Elementary, Woodlawn Elementary, Deerfield Elementary.

Colleges and universities

The University of Kansas is the largest public university in the state with total enrollment of just more than 30,000 students (including approximately 3,000 students at the KU Medical Center in Kansas City, KS).[103] It has more than 170 fields of study and the nationally known Kansas Jayhawks athletics programs. Haskell Indian Nations University offers free tuition to members of registered Native American tribes. However, students are required to pay semester fees similar to many other colleges in the United States. It has an average enrollment of more than 1,000 students representing all 50 states and 150 tribes. Haskell University is the home of the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame and the Haskell Cultural Center.

In 2010, Lawrence was named one of America's 10 best college towns by Parents & Colleges. Lawrence also was included in lists of top college towns in 2010 by the American Institute for Economic Research, MSN and MSNBC.[44]

Libraries

The first library in Lawrence was started in October 1854 and was a subscription library costing $1 a year. After the Lawrence Massacre destroyed the library, a new one was started in 1865 and placed under city jurisdiction in 1871. In 1902, Peter Emery successfully got a grant from Andrew Carnegie to build a new library at 9th and Vermont Streets. The Lawrence Public Library opened in 1904. A new library to replace the aging and outdated Carnegie Building was completed in 1972 at 7th and Vermont Streets with voters approving a bond issue in 2010 to expand and update the building.[104] During construction, the library moved to 7th and New Hampshire in the former Borders bookstore. The new library opened in July 2014.[105]

Media

One of the first businesses established in Lawrence was a newspaper, the Herald of Freedom began in October 1854 and ceased publication in 1859. In August 1885, the Lawrence Daily Journal began and the Lawrence Daily World began in June 1895. These papers would merge in 1911 to become the Lawrence Journal-World although the masthead lists the founding as 1858, probably in reference to the Herald of Freedom. Other newspapers include The University Daily Kansan, an independent student newspaper from the University of Kansas and Change of Heart, a street newspaper sold by homeless vendors.

Radio stations in Lawrence include KLWN an AM station that began in 1951. FM stations are KU stations KJHK and KANU, which broadcast Kansas Public Radio, a NPR affiliate.[106] K241AR, a Christian station that broadcasts Air 1,[107] KCIU-LP, a religious station, KKSW, formerly KLZR, is a Top 40 station. KMXN, a country station, also broadcasts from Lawrence but is licensed to Osage City.[108]

Lawrence is in the Kansas City television market, but viewers can also receive stations from the Topeka market as well.[109] Television stations currently licensed and/or broadcasting from Lawrence are KUJH-LP, a University of Kansas student station, KMCI which broadcasts from Kansas City, Missouri,[110] and 6 News Lawrence, a local news station owned by Wide Open West (WOW).[111]

From 1947 until 1981, Lawrence was the location of the Centron Corporation, one of the major industrial and educational film production companies in the United States at the time. The studio was founded by two University of Kansas graduates and employed university students and faculty members as advisers and actors. Also, many talented local and area filmmakers were given their first chances to make movies with Centron, and some stayed for decades. Others went on to successful careers in Hollywood. One of these local residents, Herk Harvey, was employed by Centron as a director for 35 years and in the middle of his tenure there he made a full-length theatrical film, Carnival of Souls, a horror cult film shot mostly in Lawrence and released in 1962. The Centron Corporation soundstage and residing building is now called Oldfather Studios and houses the University of Kansas film program.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Interstate 70, as the Kansas Turnpike, runs east–west along the northern edge of the city, interchanging with U.S. Route 59 which runs north–south along North 2nd Street, 6th Street and Iowa Street. Another east–west route, U.S. Route 40, runs through northern Lawrence along 6th Street roughly 2 miles south of I-70. U.S. 40 runs concurrently east–west with U.S. 59 for approximately 1 mile between Iowa Street and Massachusetts Street. The two routes turn north before crossing I-70. One half mile north of I-70, U.S. 40 splits from U.S. 59 and turns east, running concurrently with U.S. 24, exiting the city.

K-10, an east–west state highway, enters the city from the east along 23rd Street, then turns south, running concurrently with U.S. 59 for 1.5 miles before splitting off and continuing west and finally north around western Lawrence as a bypass, terminating at an interchange with I-70 northwest of the city.[51] The K-10 South Lawrence Trafficway is a project with the goal to connect K-10 and the Kansas Turnpike. Currently, to transfer between K-10 and the Kansas Turnpike, drivers must use Lawrence city streets. The K-10 South Lawrence Trafficway, already partially built, was proposed as a solution to traffic, air quality, and safety concerns. However, the project has received criticism and been the subject of many protests for more than a decade because of opposition to the trafficway being built through the Haskell-Baker Wetlands.[112] More recently, it appears completion of the project is underway. In June 2011, the Kansas Department of Transportation announced it would provide $192 million to complete the trafficway[113] and in July 2012, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court's ruling that all necessary permits were properly obtained and that construction could commence.[114] As for the wetlands, about 56 acres will be taken for the construction of the South Lawrence Trafficway; because of this approximately 380 acres of manmade wetlands will be developed adjacent to the site.

Two bus systems operate in the city. Lawrence Transit, known locally as "The T", is a public bus system operated by the city, and KU on Wheels is operated by the University of Kansas.[115] Together, the two systems operate 18 bus routes in the city.[116] Both systems are free to KU students, faculty, and staff.[117] Both systems are owned and operated by MV Transportation. Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service with a stop in Lawrence.[118] In addition, the Johnson County, Kansas bus system provides inter-city transport between Lawrence and Overland Park college campuses in a route known as the K-10 Connector.[119]

Lawrence Municipal Airport is northeast of the city, immediately north of U.S. 40. Publicly owned, it has two runways and is used for general aviation.[120] The nearest airport with commercial airline service is Kansas City International Airport which is located approximately 50 miles northeast of downtown Lawrence.[121]

Two Class I railroads, BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad (UP), have lines which pass through Lawrence.[122] The BNSF line enters the city from the east and exits to the north, roughly following the course of the Kansas River. The UP line does the same on the north side of the river, running through the city's northeast corner.[51] Using the BNSF trackage, Amtrak provides passenger rail service on its Southwest Chief line between Chicago and Los Angeles.[50][123] Amtrak's Lawrence station is located a few blocks east of downtown.[124]

Sister cities

Lawrence has three sister cities through Sister Cities International:[125]

-

Eutin, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany - 1989

Eutin, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany - 1989 -

Hiratsuka, Japan - 1990

Hiratsuka, Japan - 1990 -

Iniades, Greece - 2009

Iniades, Greece - 2009

Notable people

In popular culture

In addition to serving as the setting for a number of science fiction writer James Gunn's novels, including The Immortals (1964), which was the basis for the ABC television movie and TV series The Immortal (1969–1971), Lawrence was also the setting for the 1983 television movie The Day After, and has figured into other recent science fiction and speculative works. Dean and Sam Winchester, brothers of the Supernatural TV series, hail from Lawrence, and the city has been referenced numerous times throughout the show's history. Lawrence was destroyed in the 2006 TV Series Jericho.[126]

American folk singer Josh Ritter's song entitled Lawrence KS is on the 2002 album Golden Age of Radio. Cross Canadian Ragweed's 2007 album Mission California features a song entitled "Lawrence," which was inspired by a homeless family the band encountered near Christmas while visiting the town.[127]

Lawrence is the default starting point for the map program Google Earth (2005). This location was set by Brian McClendon, a 1986 graduate of the University of Kansas and director of engineering for Google Earth.[lower-alpha 2][128]

See also

- Great Flood of 1951

- Jayhawker

- Lawrence Massacre

- Lied Center of Kansas

- Mount Oread Civil War posts

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Douglas County, Kansas

Notes

- ↑ "Pearson Government Solutions" was spun-out from Pearson PLC, and became "Vangent", which in turn was purchased by General Dynamics in 2011.

- ↑ Older versions of Google Earth have a default position that, when the program launches, is centered on the city of Lawrence; whereas newer versions of the program center on Lawrence on the initial run, but center on the user's own location on subsequent launches.

References

- ↑ "Lawrence, Kansas". City-Data.com. Onboard Informatics. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- 1 2 Lawhorn, Chad (August 18, 2015). "Signs Point to Amyx as Next Mayor; Questions About Whether Commissioners Need City Credit Cards; Neighbors Expressing Safety Concern Near New York Elementary". Lawrence Journal-World. The World Company. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ↑ "City Manager". LawrenceKS.org. City of Lawrence, Kansas. 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- 1 2 3 GNIS entry for Lawrence, Kansas; USGS; October 13, 1978.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- 1 2 "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "2010 City Population and Housing Occupancy Status". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- 1 2 "About Us | City of Lawrence, KS". Ci.Lawrence.KS.us. November 21, 1996. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "1883 Cutler's History of Kansas, Douglas County, Lawrence". A.T. Andreas. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ↑ James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Ballantine Books, 1989), p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "1883 Cutler's History of Kansas, Douglas County, Early Settlers". A.T. Andreas. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ↑ Brackman, Barbara (1997). Kansas Trivia. Thomas Nelson Inc. p. 22.

- ↑ "Kansas Post Offices, 1828-1961 (archived)". Kansas Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- 1 2 "1883 Cutler's History of Kansas, Douglas County, Kansas, Early Newspapers". Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Wakarusa War - KS-Cyclopedia - 1912". Skyways.Lib.KS.us. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "1883 Cutler's History of Kansas, Douglas County, Events of 1855". A.T. Andreas. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ↑ "The Sack of Lawrence, Kansas, 1856". EyeWitnessToHistory.com. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "1860 Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. April 20, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "The Lawrence Massacre, Part One". Kancoll.org. June 30, 1994. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "DOUGLAS County, Part 9". Kancoll.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "1883 Cutler's History of Kansas, Douglas County, University of Kansas". A.T. Andreas. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Our History". Bowersockpower.com. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Douglas County, Part 11". KanColl.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "HINU | About Haskell". Haskell.edu. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Douglas County, Part 11". Kancoll.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Kansas Historical Quarterly - Beautiful Bismarck - Kansas Historical Society". KSHS.org. September 6, 1987. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- 1 2 "The Watkins Building | Watkins Community Museum of History | Douglas County Kansas". WatkinsMuseum.org. April 14, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Flood of 1903 - Kansapedia - Kansas Historical Society". KSHS.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Dary, David. Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas: An Informal History. Lawrence: Allen Press, 1981.

- ↑ Juracek, Kyle E.; Perry, Charles A.; Putnam, James E. "USGS - The 1951 Floods in Kansas Revisited". KS.Water.USGS.gov. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "The Local Flood Hazard | City of Lawrence, KS - Planning & Development Services". LawrenceKS.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "South Park | City of Lawrence, Kansas - Parks and Recreation". LawrenceKS.org. August 31, 1910. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Kansas Historical Quarterly - Theodore Roosevelt's Osawatomie Speech - Kansas Historical Society". KSHS.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "History of Lawrence, Kansas". History.Lawrence.com. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Lawrence Memorial Hospital - History". LMH.org. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Hospital Quality Awards". Lawrence Memorial Hospital. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Lawrence Journal-World - Google News Archive Search". News.Google.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ List of Prisoner Of War (POW) Camps in Kansas, Genealogy Tracer

- ↑ Lawhorn, Chad (November 6, 2014). "Downtown Lawrence retailer of 67 years to close its doors". Town Talk. Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

Francis Sporting Goods is closing its downtown store after 67 years in business. The company is not going entirely out of business. Owner Jon Francis ...will solely focus on its team business, which sells uniforms and equipment to everybody from youth baseball teams to college football programs.

- ↑ Niccum, Jon (November 19, 2003). "Fallout from 'The Day After'". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "The Story of The Free State Brewing Co. | Free State Brewing Company". FreeStateBrewing.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ Best Places to Retire: Lawrence, KS

- 1 2 Lawrence again named a top-10 college town

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Blackmar, Frank W., ed. (1912). "Mount Oread". Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. 2. Chicago: Standard. p. 330.

- ↑ "TopoQuest Map Viewer". TopoQuest. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Geography". Geohydrology of Douglas County. Kansas Geological Survey. Dec 1960. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- ↑ "2003-2004 Official Transportation Map" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. 2003. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- 1 2 "General Highway Map - Douglas County, Kansas" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. May 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "City of Lawrence" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. January 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- ↑ "About Us · City of Lawrence, Kansas". web.archive.org. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Parks & Trails · City of Lawrence, Kansas". web.archive.org. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (March 1, 2007). "Updated Köppen-Geiger climate classification map" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions (4): 439–473. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Station Name: KS LAWRENCE". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- 1 2 "Average weather for Lawrence, KS". The Weather Channel. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ↑ E. U. Bond (Mayor); R. D. Brooks (City Clerk) (November 9, 2006). "Ordinance No 973 (manuscript)" (PDF). Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ↑ http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natregsearchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=41

- ↑ http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natregsearchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=42

- ↑ http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natregsearchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=26

- ↑ http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natregsearchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=8

- ↑ http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natregsearchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=37

- ↑ http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natregsearchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=56

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ "When Off-Campus College Students are Excluded, Poverty Rates Fall in Many College Towns - Poverty - Newsroom - U.S. Census Bureau". web.archive.org. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "A study in poverty, or how college towns skew Census data - Policy Blog NH". policyblognh.org. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- 1 2 "Kansas Top Employers - KS Major Employers". MBA-Today.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lawhorn, Chad (July 21, 2002). "Prosoco Sweeps into "Alliance"". Lawrence Journal World. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ↑ Slater, Lindsey (July 21, 2007). "History of East Hills Business Park" (PDF). LawrenceKS.org. City of Lawrence. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- 1 2 "South Park". LawrenceKS.org. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Centennial Park". LawrenceKS.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Sesquicentennial Point". LawrenceKS.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "100 Years Ago: New Bowersock Opera House Opens to Cheering Public". LJWorld.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Bowersock Opera House - From the Ground Up". Luna.KU.edu. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "History". EldridgeHotel.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Ghost". EldridgeHotel.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ Barker, Matt (December 10, 2011). "Roundball Preview: No. 2 Ohio State vs. No. 13 Kansas". BuckeyeBanter.com. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ↑ "KU Facilities :: Allen Fieldhouse". KUAthletics.com. CBS Interactive. 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- 1 2 "Oak Hill Cemetery". LawrenceKS.org. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Memorial Park Cemetery". LawrenceKS.org. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places—Nomination Form". Image1.NPS.gov. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "This Old House Full of Lawrence History". LJWorld.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form". Image1.NPS.gov. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ "History of The Castle - The Castle Tea Room". CastleTeaRoom.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Schools that rock" (PDF). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ "36 hours in Lawrence, Kan.". The New York Times. February 25, 2005. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Esquire's Best Bars in America". Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ Werthheimer, Linda (December 31, 2005). "'International Dadaism Month' in Lawrence, Kansas". NPR.

- ↑ "International Dadaism Month Begins Today". Huffington Post. February 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Wakarusa Officials Reflect On Event". Lawrence Journal-World. June 24, 2005. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ↑ Lawhorn, Chad (August 10, 2008). "Wakarusa Fest may not play on". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Lawrence City Commissioners

- ↑ Two Kansas counties stand alone...

- ↑ 2004 Presidential Election Results

- ↑ 2000 Presidential Election Results

- ↑ 1996 Presidential Election Results

- ↑ 1992 Presidential Election Results

- ↑ 2008 Presidential Election Results

- ↑ 2012 Presidential Election Results

- ↑ "Voters will see big changes from new redistricting plan / LJWorld.com". www2.ljworld.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lawhorn, Chad (August 1, 2007). "Domestic partnership registry opens today". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Lawrence Public Schools / HomePage". usd497.org. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "KU News - KU enrollment breaks 30,000; sets records in minority enrollment, ACT scores". news.ku.edu. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Lawrence Public Library". Lawrence.Lib.KS.us. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "New Lawrence Library's Grand Opening Dazzles Eager Readers". LJWorld.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "About KJHK 90.7 FM". KJHK. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Air 1 Stations". Air 1. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Contact Us". KMXN. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Kansas TV Markets". EchoStar Knowledge Base. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ↑ "About NBC Action News & 38 the Spot". E.W. Scripps Company. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Channel 6 Lawrence, KS - A Division of WOW". 6newslawrence.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "South Lawrence Trafficway". Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ "KDOT commits $192 million to complete South Lawrence Trafficway". Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ "South Lawrence Trafficway legal fight ends with passing of deadline". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "About Us". Lawrence Transit. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Route Map" (PDF). Lawrence Transit. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Fares & Bus Passes". KU on Wheels. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Locations : States : Kansas". Greyhound Lines. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "The Jo Routes". Johnson County Transportation. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ↑ "KLWC - Lawrence Municipal Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Travel". Lawrence Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Kansas Operating Division" (PDF). BNSF Railway. April 1, 2009. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Southwest Chief". Amtrak. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Lawrence, KS (LRC)". Amtrak. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved April 25, 2010. Sister Cities International.

- ↑ "N. Lawrence looking to benefit from publicity for CBS drama / LJWorld.com". www2.ljworld.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ Mass St. Muse

- ↑ "Lawrence is the center of the world for more than Jayhawk fans | Kansan.com". Kansan.com. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

Further reading

Lawrence

- History of Lawrence, Kansas: from the First Settlement to the close of the Rebellion; Richard Cordley; E.F. Caldwell; 360 pages; 1895. (Download 20MB PDF eBook)

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Lawrence (Kansas)". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Lawrence (Kansas)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Lawrence (Kansas)". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Lawrence (Kansas)". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Lawrence (Kansas)". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

Kansas

- History of the State of Kansas; William G. Cutler; A.T. Andreas Publisher; 1883. (Online HTML eBook)

- Kansas : A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc; 3 Volumes; Frank W. Blackmar; Standard Publishing Co; / 955 / 824 944 / 955 / 824 pages; 1912. (Volume1 - Download 54MB PDF eBook), (Volume2 - Download 53MB PDF eBook), (Volume3 - Download 33MB PDF eBook)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lawrence, Kansas. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lawrence, Kansas. |

- Official website

- Lawrence - Directory of Public Officials

- Lawrence - Chamber of Commerce

- Lawrence - Visitors Bureau

- Daily Record, Google news archive. —PDFs for 998 issues, dating from 1889 through 1893.

- Daily World, Google news archive. —PDFs for 1,062 issues, dating from 1892 through 1895.

- Lawrence City Map, KDOT