History of fair trade

The fair trade movement has undergone several important changes since its early days following World War II. Fair trade, first seen as a form of charity advocated by religious organizations, has radically changed in structure, philosophy and approach. The past fifty years have witnessed massive changes in the diversity of fair trade proponents, the products traded and their distribution networks.

The origins of fair trade

Fair trade principles have deep roots in European societies long before the first structured alternative trading organizations (ATOs) emerged following World War II. Many of the fundamental concepts behind fair trade actually show a great resemblance with pre-capitalist ideas about the organization of the economy and society.

The notion of the ‘old moral economy’ is a fitting example of such conceptions. E. P. Thompson, in his work on 18th century England, described a society where "notions of common well being, often supported by paternalistic traditional authorities, imposed some limits on the free operations of the market".[1] Farmers were then not allowed to manipulate prices by withholding their products to wait for price increases. The actions of the middlemen were always considered legally suspect, were severely restricted and the poor were provided opportunities to buy staple foods in small parcels. Fair trade was already seen as a way to address market failures; although the concept mainly revolved around consumer, rather than producer, rights.[1]

In 1827 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a moral and economic boycott of slave-derived goods began with the formation of the "Free Produce Society", founded by Thomas M'Clintock and other abolitionist members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). In the Free produce movement, they sought to fight against slavery with a new tactic, one that emphasized the value of the honest labor of free men and women, and to try to determine the unseen added costs to goods such as cotton and sugar which came from the toil of slaves.[2] In 1830, African Americans formed the "Colored Free Produce Society", and women formed their own branch in 1831. In 1838, supporters from a number of states came together in the American Free Produce Association, which promoted their cause by seeking non-slave alternates to products from slaveholders, forming non-slave distribution channels, and publishing a number of pamphlets, tracts, and the journal Non-Slaveholder. The movement did not grow large enough to gain the benefit of the economies of scale, and the cost of "free produce" was always higher than competing goods. The national association disbanded in 1847, but Quakers in Philadelphia continued until 1856.[3]

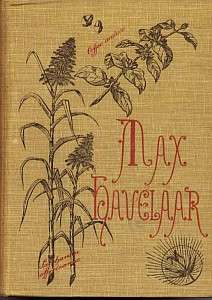

There have been a few instances in which fair trade in the 'old moral economy' was focused on producer rights: as early as 1859, Dutch author Multatuli (the pen name of Eduard Douwes Dekker) questioned the injustice of the colonial and capitalist system towards commodity producers in his novel Max Havelaar. The fictional tale recounts the story of Max Havelaar, a Nederlandse Trade Company employee, who leaves everything to work in solidarity with local Indonesian workers. This account draws a direct correlation between the wealth and the prosperity of Europe and the poverty of the suffering of other parts of the world.[4]

Early fair trade initiatives

The fair trade movement was shaped in the years following World War II. Early attempts to commercialize in Northern markets goods produced by marginalised producers were initiated by religious groups and various politically oriented non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

The Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) and SERRV International were the first, in 1946 and 1949 respectively, to develop fair trade supply chains in developing countries.[5] The products, almost exclusively handicrafts ranging from jute goods to cross-stitch work, were mostly sold by volunteers in 'charity stores' or 'ethnic shops'. The goods themselves had often no other function than to indicate that a donation had been made.[6]

Solidarity trade

The modern fair trade movement was shaped in Europe in the 1960s. Fair trade during that period was often seen as a political gesture against neo-imperialism: radical student movements began targeting multinational corporations and concerns that traditional business models were fundamentally flawed started to emerge. The global free market economic model came under attack during that period and fair trade ideals, built on a Post Keynesian economics approach to economies where price is directly linked to the actual production costs and where all producers are given fair and equal access to the markets, gained in popularity.[7] The slogan at the time, "Trade not Aid", gained international recognition in 1968 when it was adopted by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to put the emphasis on the establishment of fair trade relations with the developing world.[8]

In 1965 the first ATO was created: British NGO Oxfam launched "Helping-by-Selling", a program which later developed into Bridge. The scheme sold imported handicrafts in Oxfam stores in the United Kingdom and from mail-order catalogues with a circulation of almost 100,000 copies. The program was created to support the work of cooperatives and community enterprises in the developing world. The program was highly successful: it remained one of the largest and most influential in the sector and then changed in 2002 as more mainstream retailers were persuaded to carry fair trade products. Globally Oxfam still works in many countries on fair trade programs and runs hundreds of shops across Europe and Australia selling and promoting fair trade goods.

In 1969, the first Worldshop opened its doors in the Netherlands. The initiative aimed at bringing the principles of fair trade to the retail sector by selling almost exclusively goods such as handcrafts produced under fair trade terms in "underdeveloped regions". The first shop was run by volunteers and was so successful that dozens of similar shops soon went into business in the Benelux countries, Germany and in other Western European countries.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, important segments of the fair trade movement worked to find markets for products from countries that were excluded from the mainstream trading channels for political reasons. Thousands of volunteers sold coffee from Angola and Nicaragua in Worldshops, in the back of churches, from their homes and from stands in public places, using the products as a vehicle to deliver their message: give disadvantaged producers in developing countries a fair chance on the world’s market, and you support their self-determined sustainable development. The alternative trade movement blossomed, if not in sales, then at least in terms of dozens of ATOs being established on both sides of the Atlantic, of scores of Worldshops being set up, and of well-organized actions and campaigns attacking exploitation and foreign domination, and promoting the ideals of Nelson Mandela, Julius Nyerere and the Nicaraguan Sandinistas: the right to independence and self-determination, to equitable access to the world’s markets and consumers.

Handcrafts vs. agricultural goods

In the early 1980s, Alternative Trading Organizations faced a major challenge: the novelty of some fair trade products started wearing off, demand reached a plateau and some handicrafts began to look "tired and old fashioned" in the marketplace.[9] The decline of segments of the handicrafts market forced fair trade supporters to rethink their business model and their goals. Moreover, fair trade supporters during this period became increasingly worried by the impact of the fall of agricultural commodity prices on poor producers. Many then believed it was the movement's responsibility to address the issue and to find innovative remedies to address the ongoing crisis in the industry.

In the subsequent years, fair trade agricultural commodities played an important role in the growth of many ATOs: successful on the market, they offered a renewable source of income for producers and provided Alternative Trading Organizations the perfect substitute to the stagnating handicrafts market. The collapse of the International Coffee Agreement[10] in 1989 fueled the extraordinary growth of the fair trade coffee market, providing a powerful narrative for a new breed of fair trade brand that engaged producers directly in consumer operations. Cafédirect is a good example of this new thinking and was the first fair trade brand to be found in UK supermarkets. Dedicated to the mainstream, Cafédirect created focused on consumer engagement and language and built a reputation for quality, justifying its premium positioning with the tag-line "We pay more, so you get the pick of the crop".

The first fair trade agricultural products were coffee and tea, quickly followed by dried fruits, cocoa, sugar, fruit juices, rice, spices and nuts. Coffee quickly became the main growth engine behind fair trade: between 25 and 50% of the total alternative trading organization turnover in 2005 came from coffee sales.[11]

While a sales value ratio of 80% handcrafts to 20% agricultural goods was the norm in 1992, in 2002 handcrafts accounted for 25.4% of sales while commodity food lines were up at 69.4%.[12] The transition to agricultural commodities was further highlighted in 2002, when Oxfam decided to abandon its loss-making handcrafts trading program after 27 years of existence. Oxfam’s move had significant consequences on the entire fair trade movement. Some ATOs saw this as an opportunity to restructure and partner up with mainstream businesses in an effort to find economic efficiencies and broaden their appeal, while others (such as Alternativ Handel in Norway), unable to adjust to the market and plagued by financial difficulties, were forced to close.

Today, many ATOs still exclusively sell handcrafts - which they judge culturally and economically preferable to agricultural commodities. While these are still considered fair trade flagship products, academics have described them as a niche market that now only appeals to relatively small segments of the population, mostly fair trade core supporters who buy products on the basis of the story behind the product.[9]

Rise of labelling initiatives

Note: Customary spelling of Fairtrade is one word when referring to product labelling Sales of fair trade products however only really took off with the arrival of the first Fairtrade labelling initiatives. Although buoyed by ever growing sales, fair trade had been generally contained to relatively small Worldshops scattered across Europe and to a lesser extent, North America. Some felt that these shops were too disconnected from the rhythm and the lifestyle of contemporary developed societies. The inconvenience of going to them to buy only a product or two was too high even for the most dedicated customers. The only way to increase sale opportunities was to start offering fair trade products where consumers normally shop, in large distribution channels.[13] The problem was to find a way to expand distribution without compromising consumer trust in fair trade products and in their origins.

A solution was found in 1988, when the first Fairtrade label, Max Havelaar, was launched under the initiative of Nico Roozen, Frans van der Hoff and Dutch ecumenical development agency Solidaridad. The independent certification allowed the goods to be sold outside the worldshops and into the mainstream, reaching a larger consumer segment and boosting fair trade sales significantly. The labeling initiative also allowed customers and distributors alike to track the origin of the goods to confirm that the products were really benefiting the producers at the end of the supply chain.[14]

On the producer end, the Max Havelaar initiative offered disadvantaged producers following various social and environmental standards a fair price, significantly above the market price, for their crop. The coffee, originating from the UCIRI cooperative in Mexico, was imported by Dutch company Van Weely, roasted by Neuteboom, sold directly to world shops and, for the first time, to mainstream retailers across the Netherlands.

The initiative was groundbreaking as for the first time Fairtrade coffee was sold in supermarkets and mass-retailers, therefore reaching a larger consumer segment. Fairtrade labelling also allowed consumers and distributors alike to track the origin of the goods to confirm that the products were really benefiting the farmers at the end of the supply chain. The initiative was a great success and was replicated in several other markets: in the ensuing years, similar non-profit Fairtrade labelling organizations were set up in other European countries and North America, called "Max Havelaar" (in Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Norway and France), "Transfair" (in Germany, Austria, Luxembourg, Italy, the United States, Canada and Japan), or carrying a national name: "Fairtrade Mark" in the UK and Ireland, "Rättvisemärkt" in Sweden, and "Reilu Kauppa" in Finland.

| Retail Value Global Fairtrade Sales[15] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Sales Value | |

| ---- | ||

| 2007 | € 2 381 000 000 | |

| 2006 | € 1 623 000 000 | |

| 2005 | € 1 141 570 191 | |

| 2004 | € 831 523 066 | |

| 2003 | € 554 766 710 | |

| 2002 | € 300 000 000 | |

| 2001 | € 248 000 000 | |

| 2000 | € 220 000 000 | |

Initially, the Max Havelaars and the Transfairs each had their own Fairtrade standards, product committees and monitoring systems. In 1994, a process of convergence among the labelling organizations – or "LIs" (for "Labelling Initiatives") – started with the establishment of a TransMax working group, culminating in 1997 in the creation of Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO). FLO is an umbrella organization whose mission is to set the Fairtrade standards, support, inspect and certify disadvantaged producers and harmonize the Fairtrade message across the movement.

In 2002, FLO launched a new International Fairtrade Certification Mark. The goals of the launch were to improve the visibility of the mark on supermarket shelves, facilitate cross border trade and simplify export procedures for both producers and exporters.

The Fairtrade Certification Mark harmonization process is still under way – today, all but two labelling initiatives (Transfair USA & TransFair Canada) have adopted the new International Fairtrade Certification Mark. Full transition to the new Fairtrade Mark should become reality as it gradually replaces the old certification marks at various speeds in various countries.

In January 2004, FLO was divided into two independent organizations: FLO International, which sets Fairtrade standards and provides producer business support, and FLO-CERT, which inspects and certifies producer organizations. The aim of the split was to ensure the impartiality, the independence of the certification process and compliance with ISO 65 standards for product certification bodies.

At present, over 20 Labelling Initiatives are members of FLO International. There are now Fairtrade Certification Marks on dozens of different products, based on FLO’s certification for coffee, tea, rice, bananas, mangoes, cocoa, cotton, sugar, honey, fruit juices, nuts, fresh fruit, quinoa, herbs and spices, wine and footballs etc.

WFTO and the FTO Mark

In an effort to complement the Fairtrade certification system and allow for example handcraft producers to also sell their products outside worldshops, the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO), formerly the International Fair Trade Association (founded 1989), launched a new Mark to identify fair trade organizations in 2004 (as opposed to products in the case of Fairtrade). Called the FTO Mark, it allows consumers to recognize registered Fair Trade Organizations worldwide and guarantees that standards are being implemented regarding working conditions, wages, child labour and the environment.

The FTO Mark gave for the first time Fair Trade Organizations (including handcrafts producers) definable recognition amongst consumers, existing and new business partners, governments and donors.

Fair trade today

Global fair trade sales have soared over the past decade. The increase has been particularly spectacular among Fairtrade labelled goods: In 2007, Fair trade certified sales amounted to approximately €2.3 billion (US $3.62 billion) worldwide, a 47% year-to-year increase.[16] As per December 2006, 569 producer organizations in 58 developing countries were FLO-CERT Fairtrade certified and over 150 were WFTO registered.[17][18]

References

- 1 2 Fridell, Gavin (2003). Fair Trade and the International Moral Economy: Within and Against the Market. CERLAC Working Paper Series.

- ↑ Newman, Richard S. Freedom's Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers, NYU Press, 2008, p. 266. ISBN 0-8147-5826-6

- ↑ Hinks, Peter and McKivigan, John, editors. Williams, R. Owen, assistant editor. Encyclopedia of antislavery and abolition, Greenwood Press, 2007, pp. 267–268. ISBN 0-313-33142-1

- ↑ Redfern A. & Snedker P. (2002) Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement. International Labor Office.

- ↑ International Fair Trade Association. (2005). Crafts and Food. Accessed August 2, 2006.

- ↑ Hockerts, K. (2005). The Fair Trade Story. p1

- ↑ Redfern A. & Snedker P. (2002) Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement. International Labor Office. p4

- ↑ International Fair Trade Association. (2005). Where did it all begin? URL accessed on August 2, 2006.

- 1 2 Redfern A. & Snedker P. (2002) Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement. International Labor Office. p6

- ↑ "Coffee Price Talks Foreseen - New York Times". Nytimes.com. 1989-11-25. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ↑ International Fair Trade Association. (2005). Market Access and Fair Trade Labeling. URL accessed on August 2, 2006.

- ↑ Nicholls, A. & Opal, C. (2004). Fair Trade: Market-Driven Ethical Consumption. London: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Renard, M.-C., (2003). Fair Trade: quality, market and conventions. Journal of Rural Studies, 19, 87-96.

- ↑ Redfern A. & Snedker P. (2002) Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement. International Labor Office. p7

- ↑ Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (2006). Annual Reports 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 URL accessed on June 16, 2008.

- ↑ Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (2008). http://www.fairtrade.net/single_view.html?&cHash=d6f2e27d2c&tx_ttnews[backPid]=104&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=41. URL accessed on May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (2007). www.fairtrade.net. URL accessed on May 24, 2007.

- ↑ IFAT. (2006) The FTO Mark. URL accessed on October 30, 2006.