Haplocanthosaurus

| Haplocanthosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 155–152 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted H. delfsi skeleton, Cleveland Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Diplodocoidea |

| Family: | †Haplocanthosauridae Bonaparte, 1999 |

| Genus: | †Haplocanthosaurus Hatcher, 1903 (conserved name) |

| Type species | |

| †Haplocanthosaurus priscus (Hatcher, 1903) (conserved name) | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Haplocanthosaurus (meaning "simple spined lizard") is a genus of sauropod dinosaur. Two species, H. delfsi and H. priscus, are known from incomplete fossil skeletons. It lived during the late Jurassic period (Kimmeridgian stage), 155 to 152 million years ago.[2] The type species is H. priscus, and the referred species H. delfsi was discovered by a young college student named Edwin Delfs in Colorado, USA. Haplocanthosaurus specimens have been found in the very lowest layer of the Morrison Formation, along with Hesperosaurus, Brontosaurus yahnahpin, and Allosaurus jimmadensi.[3]

Description

Haplocanthosaurus was one of the smallest sauropods of the Morrison.[3] While some Morrison sauropods could reach lengths of over 20 meters (or over 66 feet), Haplocanthosaurus was smaller, reaching a total length of 14.8 meters (49 feet) and an estimated weight of 12.8 metric tons.[4]

Specimens

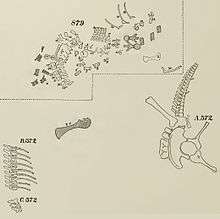

There are four known specimens of Haplocanthosaurus: one of H. delfsi, and three of H. priscus. Of these, the type of H. delfsi is the only one complete enough to mount. The mounted specimen of H. delfsi now stands in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, albeit with a completely speculative replica skull, as the actual skull was not recovered. Present in stratigraphic zones 1, 2, and 4.[5] If the specimen of "Morosaurus" agilis is included, Haplocanthosaurus is also known from fragments of a skull and cervicals 1-3.[6] Recently described specimens from a different region of the Morrison Formation were assigned to Haplocanthosaurus in 2014. The study describing them noted that Haplocanthosaurus is known for certain from at least four specimens, assigned to H. priscus (CM 572), H. utterbacki (=H. priscus; CM 879), H. delfsi (CMNH 10380), and H. sp. (MWC 8028). Up to seven additional specimens have been assigned to Haplocanthosaurus? of Haplocanthosauridae indet.[1]

Skeleton

Haplocanthosaurus is known from many elements, mostly of vertebra. In the middle and cervical caudals of Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, Cetiosaurus and Haplocanthosaurus, the intraprezygapophyseal lamina is separate from the root of the neural canal by a vertical midline lamina. In the last few caudals and the most cranial dorsals, the lateral edge of the prezygapophyseal lamina becomes widened and roughened. Hatcher (1901) interpreted this as forming the attachment area for the muscles from which the scapular blade was suspended.[6]

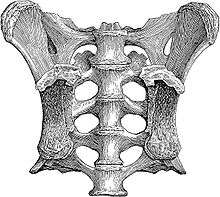

The dorsoventrally elongate oval outlines are characteristic of Haplocanthosaurus with only Camarasaurus also possessing them. The parapophyses remaining as oval facets on the craniolateral margin, and the sacral spines 1-3 fused are also found in both Haplocanthosaurus and Camarasaurus.[6]

The Cetiosaurus specimen OUMNH J13695 has a low horizontal ridge on each of its lateral surfaces, creating a slightly subhexagonal transverse cross-section, and that feature is also seen on Cetiosauriscus, the anterior caudals of Haplocanthosaurus, and caudals 15-30 of Omeisaurus. Also, the area around the periphery of each articullar face is flattened, creating a ‘bevelled’ appearance, and also occurs in Haplocanthosaurus and Cetiosauriscus.[7]

Distinguishing characteristics

Haplocanthosaurus is distinguished by dorsal vertebra lacking cranial centrodiapophyseal laminae. Also, it is distinguished by elongate intrapostzygapophyseal laminae, dorsoventrally directed dorsal transverse processes that approach the height of the neural spines, and the distal end of the scapular blade being dorsally and ventrally expanded.[6]

Classification

Haplocanthosaurus priscus was originally named Haplocanthus priscus by John Bell Hatcher in 1903. Soon after his original description, Hatcher came to believe the name Haplocanthus had already been used for a genus of acanthodian fish (Haplacanthus, named by Louis Agassiz in 1845), and was thus preoccupied. Hatcher re-classified his sauropod later in 1903, giving it the new name Haplocanthosaurus.[8] However, the name was not technically preoccupied at all, since there was a variation in spelling: the fish was named Haplacanthus, not Haplocanthus. While Haplocanthus technically remained the valid name for this dinosaur, Hatcher's mistake was not noticed until many years after the name Haplocanthosaurus had become fixed in scientific literature. When the mistake was finally discovered, a petition was sent to the ICZN (the body which governs scientific names in zoology), which officially discarded the name Haplocanthus and declared Haplocanthosaurus the official name (ICZN Opinion #1633).

Originally described as a "cetiosaurid", José Bonaparte decided in 1999 that Haplocanthosaurus differed enough from other sauropods to warrant its own family, the Haplocanthosauridae.[9]

Phylogenetic studies have failed to clarify the exact relationships of Haplocanthosaurus with any certainty. Studies have variously found it to be more primitive than the neosauropods,[10] a primitive macronarian (related to the ancestor of more advanced forms such as Camarasaurus and the brachiosaurids),[11] or a very primitive diplodocoid, more closely related to Diplodocus than to titanosaurs, but more primitive than rebbachisaurids.[12]

In 2005, Darren Naish and Mike Taylor reviewed the various proposed positions of Haplocanthosaurus in their study of diplodocoid phylogeny. They found it could be a non-neosauropod eusauropod, a basal macronarian, or a basal diplodocoid.[13] In 2011, an analysis by Whitlock recovered Haplocanthosaurus as the basalmost member of the Diplodocoidea, the third potentiality of Taylor & Naish.[14] In 2015, a specimen-level phylogenetic analysis was published, finding Haplocanthosaurus to be a confirmed diplodocoid, either very basal, or more derived than rebbachisaurids. Their implied weighting cladogram is shown below.[15]

| Diplodocoidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haplocanthosaurus. |

- 1 2 Forster, J.R.; Wedel, M.J. (2014). "Haplocanthosaurus (Saurischia: Sauropoda) from the lower Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) near Snowmass, Colorado" (PDF). Volumina Jurassica. 12 (2): 197–210. doi:10.5604/17313708.1130144.

- ↑ Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1.

- 1 2 Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp.

- ↑ Mazzetta, G.V.; Christiansen, P.; Fariña, R.A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body size of some southern South American Cretaceous dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (2): 71–83. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- 1 2 3 4 Weishample, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. (2004). "The Dinosauria: Second Edition". Berkeley, University of California Press. 2: 266, 281-286, 288, 296-299, 302-302.

- ↑ Upchurch, P.; Martin, J. (2003). "The anatomy and taxonomy of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia: Sauropoda) from the Middle Jurassic of England". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23: 208–231. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[208:taatoc]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Hatcher, J.B. (1903a). "A new name for the dinosaur Haplocanthus Hatcher". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 16: 100.

- ↑ Bonaparte, J. F. (1999). "An armoured sauropod from the Aptian of northern Patagonia, Argentina." In Tomida, Y., Rich, T. H. & Vickers-Rich, P. (eds.), 1999. Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium, National Science Museum Monographs #15, Tokyo: 1-12.

- ↑ Upchurch, P (1999). "The phylogenetic relationships of the Nemegtosauridae (Saurischia, Sauropoda)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19: 106–125. doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011127.

- ↑ Wilson, J.A.; Sereno, P.C. (1998). "Early evolution and higherlevel phylogeny of sauropod dinosaurs". Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir. 5: 1–68. doi:10.2307/3889325.

- ↑ Wilson, J.A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136: 217–276. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- ↑ Taylor, M.P.; Naish, D. (2005). "The phylogenetic taxonomy of Diplodocoidea (Dinosauria: Sauropoda)". PaleoBios. 25 (2): 1–7.

- ↑ Whitlock, J.A. (2011). "A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia: Sauropoda)." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Article first published online: 12 Jan 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00665.x

- ↑ Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O.; Benson, R.B.J. (2015). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3: e857. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. PMC 4393826

. PMID 25870766.

. PMID 25870766.