Titanosaur

| Titanosaurs Temporal range: Cretaceous, 125–66 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted replica skeleton of Argentinosaurus huinculensis, Naturmuseum Senckenberg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Somphospondyli |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria Bonaparte & Coria, 2000 |

Titanosaurs (members of the group Titanosauria) were a diverse group of sauropod dinosaurs, which included Saltasaurus and Isisaurus. When the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period occurred, they were the last surviving group of long necked dinosaurs. It includes some of the heaviest creatures ever to walk the earth, such as Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus, which are estimated to have weighed up to 90 tonnes (89 long tons; 99 short tons). The group's name refers to the much earlier discovery Titanosaurus, a now dubious genus named for the mythological Titans of Ancient Greece. Together with the brachiosaurids and relatives, titanosaurs make up the larger clade Titanosauriformes.

Description

Titanosaurs had small heads, even when compared with other sauropods. The head was also wide, similar to the heads of Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus but more elongated. Their nostrils were large ('macronarian') and they all had crests formed by these nasal bones. Their teeth were either somewhat spatulate (spoon-like) or like pegs or pencils, but were always very small.

Their necks were of average length, for sauropods, and their tails were whip-like, but not as long as in the diplodocids. While the pelvis (hip area) was slimmer than some sauropods, the pectoral (chest area) was much wider, giving them a uniquely 'wide-gauged' stance. As a result, the fossilised trackways of titanosaurs are distinctly broader than other sauropods. Their forelimbs were also stocky, and often longer than their hind limbs. Their vertebrae (back bones) were solid (not hollowed-out), which may be a throwback to more basal saurischians. Their spinal column was more flexible, so they were probably more agile than their cousins and better at rearing up. Unlike other sauropods, some titanosaurs had no digits or digit bones, and walked only on horseshoe-shaped "stumps" made up of the columnar metacarpal bones.[1][2]

From skin impressions found with the fossils, it has been determined that the skin of many titanosaur species was armored with a small mosaic of small, bead-like scales around a larger scale.[3] One species, Saltasaurus, has even been discovered with bony plates, like the ankylosaurs. Studies published in 2011 also indicate that titanosaurs such as Rapetosaurus (on which the examinations were performed), may have used the osteoderms common in the various genera for storing minerals during harsh changes in climate, such as drought.[4][5] While they were all huge, many were fairly average in size compared with the other giant dinosaurs. There were even some island-dwelling dwarf species such as Magyarosaurus, probably the result of allopatric speciation and insular dwarfism.

Derived titanosaurs had biconvex vertebrae.[6] The basal condition is either amphiplaty or amphicoely.[6] Venenosaurus may have had a condition intermediate between the two.[6]

The remains of an unnamed Patagonian titanosaur found in Argentina in 2014 are from an animal estimated to have been 40 metres (130 ft) long and 20 metres (66 ft) tall, with an estimated weight of 77 tonnes (76 long tons; 85 short tons), making it among the largest if not the largest identified land animals in Earth's history.[7]

Paleobiology

Diet

Fossilized dung associated with late Cretaceous titanosaurids has revealed phytoliths, silicified plant fragments, that offer clues to a broad, unselective plant diet. Besides the plant remains that might have been expected, such as cycads and conifers, discoveries published in 2005[8] revealed an unexpectedly wide range of monocotyledons, including palms and grasses (Poaceae), including ancestors of rice and bamboo, which has given rise to speculation that herbivorous dinosaurs and grasses co-evolved.

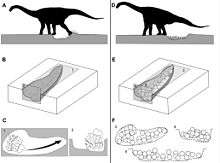

Nesting

A large titanosaurid nesting ground was discovered in Auca Mahuevo, in Patagonia, Argentina and another colony has reportedly been discovered in Spain. Several hundred female saltasaurs dug holes with their back feet, laid eggs in clutches averaging around 25 eggs each, and buried the nests under dirt and vegetation. The small eggs, about 11–12 centimetres (4.3–4.7 in) in diameter, contained fossilised embryos, complete with skin impressions. The impressions showed that titanosaurs were covered in a mosaic armour of small bead-like scales.[3] The huge number of individuals gives evidence of herd behavior, which, along with their armor, could have helped provide protection against large predators such as Abelisaurus.[9]

Range

The titanosaurs were the last great group of sauropods, which existed from about 136[10] to 66 million years ago, before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, and were the dominant herbivores of their time. The fossil evidence suggests they replaced the other sauropods, like the diplodocids and the brachiosaurids, which died out between the late Jurassic and the mid-Cretaceous Periods.

Titanosaurs were widespread. In December 2011, Argentine scientists announced titanosaur fossils have been found on Antarctica—meaning that titanosaur fossils have been found on all continents. Four well-preserved skeletons of a titanosaur species were found in Italy, a discovery first reported on 2 May 2006.[11] They are especially numerous in the southern continents (then part of the supercontinent of Gondwana). Australia had titanosaurs around 96 million years ago: fossils have been discovered in Queensland of a creature around 25 metres (82 ft) long.[12][13] Remains have also been discovered in New Zealand.[14] One of the largest ever titanosaur footprints was discovered in the Gobi desert in 2016.[15] One of the oldest remains of this group was found from the Valley of the Dinosaurs, Paraíba state of Brazil, representing a 136-million-year-old subadult individual.[10]

Systematics

The family Titanosauridae was once used for derived titanosaurs, but Wilson and Upchurch (2003) found the type genus Titanosaurus dubious based on the figures and original description.[16] Weishampel et al., in the second edition of The Dinosauria, also did not use the family Titanosauridae, and instead used several smaller titanosaur families such as Saltasauridae and Nemegtosauridae, coining Lithostrotia for derived titanosaurs.[17] A handful of Argentine sauropod workers, however, continue to use Titanosauridae for titanosaurs now placed in Lithostrotia.[18][19]

Taxonomy

Family-level taxonomy follows Holtz (2012) unless otherwise noted.[20]

- Titanosauria

- Aegyptosaurus

- Andesaurus

- Atacamatitan

- Austrosaurus

- Balochisaurus

- Barrosasaurus

- Campylodoniscus

- Diamantinasaurus

- Elaltitan

- Gobititan

- Hypselosaurus

- Iuticosaurus

- Jiangshanosaurus

- Jiutaisaurus

- Karongasaurus

- Khetranisaurus

- Laplatasaurus

- Lohuecotitan

- Macrurosaurus

- Magyarosaurus

- Malarguesaurus

- Marisaurus

- Microcoelus

- Pakisaurus

- Paludititan

- Puertasaurus

- Qingxiusaurus

- Rukwatitan

- Savannasaurus

- Sulaimanisaurus

- Titanosaurus

- Eutitanosauria

Phylogeny

In the second edition of The Dinosauria, the clade Titanosauria was defined as all sauropods closer to Saltasaurus than to Brachiosaurus.[17] Subsequent cladistic analyses have defined Titanosauria as including Saltasaurus but not Euhelopus or Brachiosaurus.[21][22]

Relationships within the Titanosauria have historically been extremely variable from study to study, complicated by the fact that clade and rank names have been applied inconsistently by various scientists. One possible cladogram is presented here, and follows a 2007 analysis by Calvo and colleagues. The authors notably used the family Titanosauridae in a broader fashion than other recent studies, and coined the new clade name Lognkosauria.[23]

| Titanosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Exhibits

- The American Museum of Natural History has a permanent exhibit of a 37 metres (121 ft) skeleton. The specimen belongs to a species which has not yet been formally named.[24][25]

- The Naturmuseum Senckenberg in Germany Argentinosaurus huinculensis

- Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada Futalongkosaurus

References

- ↑ Apesteguía, S. (2005). "Evolution of the titanosaur metacarpus". Pp. 321–345 in Tidwell, V. and Carpenter, K. (eds.) Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Day, J.J.; Norman, D.B.; Gale, A.S.; Upchurch, P.; Powell, H.P. (2004). "A Middle Jurassic dinosaur trackway site from Oxfordshire, UK". Palaeontology. 47 (2): 319–348. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00366.x.

- 1 2 Coria R.A., Chiappe L.M. (2007). "Embryonic Skin From Late Cretaceous Sauropods (Dinosauria) of Auca Mahuevo, Patgonia, Argentina". Journal of Paleontology. 81 (6): 1528–1532. doi:10.1666/05-150.1.

- ↑ "Titan dinosaur may have stored minerals in skin bones". National Geographic. 2 December 2011.

- ↑ Bishop, Adrian. "Osteoderms storing minerals helped huge dinosaurs survive – Nature – The Earth Times".

- 1 2 3 Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K. & Meyer, S. (2001). "New Titanosauriform (Sauropoda) from the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Utah", pp. 139–165 in Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. D. H. Tanke & K. Carpenter (eds.). Indiana University Press, Eds. D.H. Tanke & K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253339073.

- ↑ "'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC. 17 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ Prasad, Vandana; Strömberg, Caroline A. E.; Alimohammadian, Habib; Sahni, Ashok (18 November 2005). "Dinosaur Coprolites and the Early Evolution of Grasses and Grazers". Science. 310 (5751): 1177–1180. doi:10.1126/science.1118806. PMID 16293759.

- ↑ Vila, Bernat; Jackson, Frankie D.; Fortuny, Josep; Sellés, Albert G.; Galobart, Àngel (2010). "3-D Modelling of Megaloolithid Clutches: Insights about Nest Construction and Dinosaur Behaviour". PLoS ONE. 5 (5): e10362. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010362. PMID 20463953.

- 1 2 Ghilardi, Aline M.; Aureliano, Tito; Duque, Rudah R. C.; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Barreto, Alcina M. F.; Chinsamy, Anusuya (2016-12-01). "A new titanosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 67: 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.07.001.

- ↑ "Italians Report Major Dinosaur Discovery". PhysOrg.com. United Press International. 2 May 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ↑ Roberts, Greg (3 May 2007). "Bones reveal Queensland's prehistoric titans". The Australian. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ↑ Molnar, R. E.; Salisbury, S. W. (2005). "Observations on Cretaceous Sauropods from Australia". In Carpenter, Kenneth; Tidswell, Virginia. Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 454–465. ISBN 0-253-34542-1.

- ↑ "Bone discovery confirms big dinosaur roamed NZ". The New Zealand Herald. 24 June 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ↑ "Giant footprint could shed light on titanosaurus behaviour". BBC News Online. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Wilson, J.A. and Upchurch, P. (2003). "A revision of Titanosaurus Lydekker (Dinosauria – Sauropoda), the first dinosaur genus with a 'Gondwanan' distribution" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 1 (3): 125. doi:10.1017/S1477201903001044.

- 1 2 Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka, eds. (2004). The Dinosauria, Second Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ Calvo, J. O.; González Riga, B. J. and Porfiri, J. D. (2007). "A new titanosaur sauropod from the Late Cretaceous of Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina" (PDF). Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 485–504.

- ↑ González Riga, Bernardo J.; Previtera, Elena; Pirrone, Cecilia A. (2009). "Malarguesaurus florenciae gen. et sp. nov., a new titanosauriform (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mendoza, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 30: 135. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.06.006.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- ↑ D'Emic, Michael D. (2012). "The early evolution of titanosauriform sauropod dinosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 166 (3): 624. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00853.x.

- ↑ Mannion, Philip D.; Upchurch, Paul; Barnes, Rosie N.; Mateus, Octávio (2013). "Osteology of the Late Jurassic Portuguese sauropod dinosaur Lusotitan atalaiensis (Macronaria) and the evolutionary history of basal titanosauriforms". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 168: 98. doi:10.1111/zoj.12029.

- ↑ Calvo, J.O.; Porfiri, J. D.; González-Riga, B. J.; Kellner, A. W. (2007). "A new Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystem from Gondwana with the description of a new sauropod dinosaur". Anais Academia Brasileira Ciencia. 79 (3): 529–541. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652007000300013. PMID 17768539.

- ↑ Geggel, Laura (15 January 2016). "122-Foot Titanosaur: Staggeringly Big Dino Barely Fits into Museum". Scientific American.

- ↑ "The Titanosaur". AMNH. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

External links

- The Geological Society article Best ever titanosaur skeleton discovered in Madagascar.

- National Geographic article, Eggs Hold Skulls of Titanosaur Embryos.

- Channel 4 article, Titanosaur eggs in France.