Frances Perkins

| Frances Perkins | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th United States Secretary of Labor | |

|

In office March 4, 1933 – June 30, 1945 | |

| President |

Franklin Roosevelt Harry Truman |

| Preceded by | William Doak |

| Succeeded by | Lewis Schwellenbach |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Fannie Coralie Perkins April 10, 1880 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

May 14, 1965 (aged 85) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Paul Caldwell Wilson |

| Alma mater |

Mount Holyoke College Columbia University University of Pennsylvania |

| Religion | Episcopalianism |

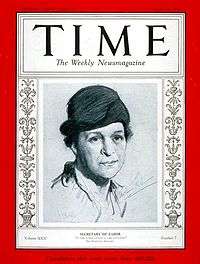

Frances Perkins Wilson (born Fannie Coralie Perkins; April 10, 1880[1][2] – May 14, 1965) was an American sociologist and workers-rights advocate who served as the U.S. Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945, the longest serving in that position, and the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. As a loyal supporter of her friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, she helped pull the labor movement into the New Deal coalition. She and Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes were the only original members of the Roosevelt cabinet to remain in office for his entire presidency.

During her term as Secretary of Labor, Perkins executed many aspects of the New Deal, including the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Administration and its successor the Federal Works Agency, and the labor portion of the National Industrial Recovery Act. With the Social Security Act she established unemployment benefits, pensions for the many uncovered elderly Americans, and welfare for the poorest Americans. She pushed to reduce workplace accidents and helped craft laws against child labor. Through the Fair Labor Standards Act, she established the first minimum wage and overtime laws for American workers, and defined the standard forty-hour work week. She formed governmental policy for working with labor unions and helped to alleviate strikes by way of the United States Conciliation Service. Perkins dealt with many labor questions during World War II, when skilled manpower was vital and women were moving into formerly male jobs.[3]

Early life

Perkins was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Susan Bean Perkins (September 1849-1927) and Frederick W. Perkins (24 August 1844-1916), the owner of a stationer's business (both of her parents originally were from Maine).[4] She spent much of her childhood in Worcester, Massachusetts. She was christened Fannie Coralie Perkins, but she changed her name to Frances[5] when she joined the Episcopal church in 1905.[6]

Perkins attended the Classical High School in Worcester. She graduated from Mount Holyoke College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in chemistry and physics in 1902. She obtained a master's degree in political science from Columbia University in 1910.[7] In the interim, she held a variety of teaching positions including a position teaching chemistry from 1904 to 1906 at Ferry Hall School (now Lake Forest Academy). In Chicago, she volunteered at settlement houses, including Hull House. In 1918 she began her years of study in economics and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School.[8]

Life and career before the cabinet position

She achieved statewide prominence as head of the New York Consumers League in 1910 and lobbied with vigor for better working hours and conditions. Perkins also taught as a professor of sociology at Adelphi College.[9] The next year, she witnessed the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a pivotal event in her life. It was because of this event that Frances Perkins would leave her office at the New York Consumers League and become the executive secretary for the Committee on Safety of the City of New York.[6]

In 1913, Perkins married New York economist Paul Caldwell Wilson. She kept her birth name, defending her right to do so in court. The couple had a daughter, Susanna. Both father and daughter were described by biographer Kirstin Downey as having "manic-depressive symptoms".[10] Wilson was frequently institutionalized for mental illness.[11] Perkins was the sole support for her household.[12]

Prior to moving to Washington, DC, Perkins held various positions in New York State government. She had gained respect from the political leaders in the state of New York. In 1919 she was added to the Industrial Commission of the State of New York by Governor Alfred Smith.[6] In 1929 the newly elected New York governor, Franklin Roosevelt, appointed Perkins as the inaugural Commissioner of the New York State Department of Labor.[13]

Having earned the co-operation and respect of various political factions, Perkins ably helped put New York in the forefront of progressive reform. She expanded factory investigations, reduced the workweek for women to 48 hours and championed minimum wage and unemployment insurance laws. She worked vigorously to put an end to child labor and to provide safety for women workers.[6]

Cabinet career

In 1933, Roosevelt appointed Perkins as Secretary of the Department of Labor, a position she held for twelve years, longer than any other Secretary of Labor. She became the first woman to hold a cabinet position in the United States and thus, became the first woman to enter the presidential line of succession. With few exceptions, President Roosevelt consistently supported the goals and programs of Secretary Perkins.

As Secretary of Labor, Perkins played a key role in the cabinet by writing New Deal legislation, including minimum-wage laws. Her most important contribution, however, came in 1934 as chairwoman of the President's Committee on Economic Security (CES). In this post, she was involved in all aspects of the reports including her hand in the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps and the She-She-She Camps.[6] Perkins also drafted the Social Security Act of 1935. On the day that the bill was signed into law, her husband escaped from a mental institution.[12][14]

In 1939, she came under fire from some members of Congress for refusing to deport the communist head of the west coast International Longshore and Warehouse Union, Harry Bridges. Ultimately, however, Bridges was vindicated by the Supreme Court.

Later life

Following her tenure as Secretary of Labor, in 1945 Perkins was asked by President Harry Truman to serve on the United States Civil Service Commission, which she did until 1952, when her husband died and she resigned from federal service. During this period, she also published a memoir of her time in FDR's administration called The Roosevelt I Knew, (1946) which offered a sympathetic view of the president.

Following her government service career, Perkins remained active as a teacher and lecturer at the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University until her death in 1965 at age 85. At Cornell she lived at the Telluride House where she was one of the intellectual community's first female members. Kirstin Downey, author of The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR'S Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, dubbed her time at the Telluride House "probably the happiest phase of her life".[15] She is buried in the Glidden Cemetery in Newcastle, Maine.[16]

Legacy

Perkins would have been famous simply by being the first woman cabinet member, but her legacy stems from her additional accomplishments. She was largely responsible for the U.S. adoption of social security, unemployment insurance, federal laws regulating child labor, and adoption of the federal minimum wage.[17]

The liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church honors Perkins with a feast day on May 13. She was the winner of the "Golden Halo" in Lent Madness 2013,[18] an educational tool hosted by Forward Movement Publications featuring the saints of the calendar of the Episcopal Church.

In 1967, the Telluride House and Cornell University's School of Industrial and Labor Relations established the Frances Perkins Memorial Fellowship.[19] In 2015, Perkins was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the 2015 LGBT History Month.[20]

Character in Historical Context

As the first female member of the presidential cabinet, Perkins had an unenviable challenge: she had to be as capable, as fearless, as tactful, as politically astute as the other Washington politicians, in order to make it possible for other women to be accepted into the halls of power after her.[21]

Perkins had a cool personality which held her aloof from the crowd. On one occasion, however, she engaged in some heated name-calling with Alfred P. Sloan, the chairman of the board at General Motors. During a punishing United Auto Workers strike, she phoned Sloan in the middle of the night and called him a scoundrel and a skunk for not giving in to the union's demands. She said, "You don't deserve to be counted among decent men. You'll go to hell when you die." Sloan's late-night response was one of irate indignation.[22]

Her results indicate her great love of workers and lower-class groups, but her Boston upbringing held her back from mingling freely and exhibiting personal affection. She was well-suited for the high-level efforts to effect sweeping reforms, but never caught the public's eye or its affection.[23]

Memorials and Monuments

The Frances Perkins Building that is the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Labor in Washington, D.C. was named in her honor in 1980.

The Frances Perkins Center is a nonprofit organization located in Damariscotta, Maine. Its mission is to fulfill the legacy of Frances Perkins through educating visitors on her work and programs, and preserving the Perkins family homestead for future generations. The Center regularly hosts events and exhibitions for the public.

Perkins remains a prominent alumna of Mount Holyoke College, whose Frances Perkins Program allows "women of non-traditional age" (i.e., age 24 or older) to complete a Bachelor of Arts degree. There are approximately 140 Frances Perkins scholars each year.[24]

Perkins and the Maine Department of Labor mural

A mural depicting Perkins was displayed in the Maine Department of Labor headquarters,[25] the native state of her parents. On March 23, 2011, Maine's Republican governor, Paul LePage, ordered the mural removed. A spokesperson for the governor said they received complaints about the mural from state business officials and from an anonymous fax charging that it was reminiscent of "communist North Korea where they use these murals to brainwash the masses".[26] LePage also ordered that the names of seven conference rooms in the state department of labor be changed, including one named after Perkins.[26] A lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court seeking "to confirm the mural's current location, ensure that the artwork is adequately preserved, and ultimately to restore it to the Department of Labor's lobby in Augusta".[27] As of January 2013, the mural resides at Maine State Museum, Maine State Library and Maine State Archives entrance.[28]

Notes

- ↑ "Fannie Perkins". 1880 United States Census. FamilySearch.org. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

; Birthplace: Ma; Age: 2 months; Head of Household: Fred Perkins; Relation: Daughter; Census Place: Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts

- ↑ "Volume 315, Page 132". Massachusetts Vital Records, 1841–1910. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

Fannie Coralie Perkins; 1880; Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts; Bith

(subscription required) - ↑ Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal, 2009, p. 337.

- ↑ 1880 Census

- ↑ Frances Perkins Collection. Mount Holyoke College Archives

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kennedy, Susan E. "Perkins, Frances." American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press, Feb. 2000. Web. 27 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Downey, Kristin. The Woman Behind the New Deal. Anchor Books, 2010, p. 11, p. 25.

- ↑ "125 Influential People and Ideas: Frances Perkins". Wharton Alumni Magazine. Wharton.upenn.edu. Spring 2007. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ↑ Frances Perkins Collection. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

- ↑ Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal, 2009, p. 380.

- ↑ Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal, 2009, p. 2.

- 1 2 Karenna Gore Schiff (2005). Lighting the Way: Nine Women Who Changed Modern America. Miramax Books/Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-5218-9. OCLC 62302578.

- ↑ Our History - New York State Department of Labor. Labor.ny.gov (1911-03-25). Retrieved on 2013-08-12.

- ↑ Alexandra Starr (February 12, 2006). "Women Warriors". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Discovering Frances Perkins". ILR School. February 24, 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ CAM Cover Story. Cornellalumnimagazine.com (1965-05-17). Retrieved on 2013-08-12.

- ↑ "Labor Hall of Fame - Frances M. Perkins". U.S. Department of Labor. 2011-06-20. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ http://www.lentmadness.org/2013/03/frances-perkins-wins-lent-madness-2013-golden-halo/

- ↑ Pasachoff, Naomi (1999). Frances Perkins: Champion of the New Deal. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 147.

- ↑ Malcolm Lazin (August 20, 2015). "Op-ed: Here Are the 31 Icons of 2015's Gay History Month". Advocate.com. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

- ↑ The Tennessean, Arts & Entertainment, 8 March 2009, "The Woman Behind the New Deal" (Kirstin Downey). "Perkins ... not only had to do more than her male counterparts to prove herself, but she had to do it while dealing with rough-and-tumble labor leaders, a husband in and out of mental institutions, condescending bureaucrats and some Congress members hell-bent on impeaching her." p. 11.

- ↑ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, p. 68, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ↑ Frances Perkins Collection. Mount Holyoke College Archives

- ↑ "Frances Perkins Program". Mount Holyoke College. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ "Judy Taylor Fine Art Studio and Gallery, featuring Portraits, Landscape Art, Figurative Art, Still Life Art, and Great Master's Reproductions". Judytaylorstudio.com. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- 1 2 Greenhouse, Steven (March 23, 2011). "Gov. Paul LePage Takes Aim at Mural to Maine's Workers". The New York Times.

- ↑ Fed. lawsuit filed over Maine labor mural removal, The Boston Globe, April 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Labor mural flap cost state more than $6,000", Portland Press Herald, January 19, 2013.

References

- Berg, Gordon. "Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies". Monthly Labor Review. 112:6 (June 1989).

- Downey, Kirstin. The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR's Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2009. ISBN 0-385-51365-8.

- Keller, Emily. Frances Perkins: First Woman Cabinet Member. Greensboro: Morgan Reynolds Publishing, 2006. ISBN 9781931798914.

- Martin, George Whitney. Madam Secretary: Frances Perkins. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1976. ISBN 0-395-24293-2.

- Pasachoff, Naomi. Frances Perkins: Champion of the New Deal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512222-4.

- Perkins, Frances. The Roosevelt I Knew. New York: Penguin Group, 1946. ISBN 0-670-60737-1.

- Severn, Bill. Frances Perkins: A Member of the Cabinet. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1976. ISBN 0-8015-2816-X.

External links

| Library resources about Frances Perkins |

| By Frances Perkins |

|---|

- Works by or about Frances Perkins at Internet Archive

- Frances Perkins Center

- Audio recording of Perkins lecture at Cornell

- A film clip "You May Call Her Madam Secretary (1987)" is available at the Internet Archive

- Frances Perkins Collection at Mount Holyoke College

- Perkins Papers at Mount Holyoke College

- Frances Perkins Collection. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

- Notable New Yorkers - Frances Perkins—Biography, photographs, and interviews of Frances Perkins from the Notable New Yorkers collection of the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University

- Columbians Ahead of Their Time, Frances Perkins biography

- Frances Perkins. Correspondence and Memorabilia. 5017. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.

- Frances Perkins Lectures at the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.

- National Women's Hall of Fame

- Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project: Frances Perkins

- U.S. Department of Labor Biography

- "Biographer Chronicles Perkins, 'New Deal' Pioneer", All Things Considered, 28 March 2009. An interview with Kirstin Downey about her biography of Frances Perkins.

- "Remembering Social Security's Forgotten Shepherd", Morning Edition, 12 August 2005. Penny Colman and Linda Wertheimer Discuss Frances Perkins

- Remarkable Frances Perkins in Twin Cities in 1935 - Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois newspaper)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Doak |

United States Secretary of Labor 1933–1945 |

Succeeded by Lewis Schwellenbach |