Clinton Presba Anderson

| Clinton Presba Anderson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 13th United States Secretary of Agriculture | |

|

In office June 30, 1945 – May 10, 1948 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Claude R. Wickard |

| Succeeded by | Charles F. Brannan |

| United States Senator from New Mexico | |

|

In office January 3, 1949 – January 3, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Carl Hatch |

| Succeeded by | Pete Domenici |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Mexico's At-large district | |

|

In office January 3, 1941 – June 30, 1945 | |

| Preceded by | John J. Dempsey |

| Succeeded by | George L. Lusk |

| 9th New Mexico State Treasurer | |

|

In office January 7, 1933 – 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Warren R. Graham, Sr. |

| Succeeded by | James J. Connelly |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 23, 1895 Centerville, South Dakota, U.S. |

| Died |

November 11, 1975 (aged 80) Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Resting place | Fairview Memorial Park in Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse(s) |

Henrietta McCartney Anderson (1899 - 1994) |

| Children |

Sherburne Presba Anderson Nancy Anderson |

| Parents |

Andrew Jay Anderson Hattie Belle Presba Anderson |

| Residence | Albuquerque, New Mexico |

| Profession | Politician |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

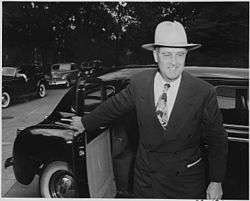

Clinton Presba Anderson (October 23, 1895 – November 11, 1975) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Representative from New Mexico from 1941 until 1945, the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture from 1945 until 1948, and a U.S. Senator from New Mexico from 1949 to 1973.

Early life and career

Anderson was born in Centerville, South Dakota, on October 23, 1895.[1] His parents were Andrew Jay and Hattie Belle Anderson (née Presba). He was educated in the public school system of South Dakota, attended Dakota Wesleyan University (1913-1915) and the University of Michigan (1915-1916), though he never received a degree from either institution.

After his father broke his back in 1916, Anderson left the University of Michigan to go home to help support his family. He worked for several months for a newspaper in Mitchell, South Dakota, until he became seriously ill with tuberculosis. He was not aware of his illness until he attempted to join the military in 1917 upon America's entrance into World War I. Doctors gave him six months to live. One gave him the advice to check himself into the Methodist Sanitarium in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He promptly did so, and while recovering there, occasionally wrote for the Herald of the Wells County.

In 1919, as soon as he was well enough to leave the sanitarium, he gained employment with the Albuquerque Journal, then called the Albuquerque Morning Journal and was sent to Santa Fe, New Mexico to cover the state's legislature. Very critical of how the Republican Party was running the state, he befriended some New Mexico Democratic legislators and gave them his ideas on bills before the legislature. Some of those ideas eventually became state law and Anderson began a lifelong association with the Democratic Party.

His long career of public service began as executive secretary of the New Mexico Public Health Association in 1919. There he raised money to fight tuberculosis, established county health programs and was instrumental in founding the state public health department.

In the early 1920s Anderson pursued private business affairs. Newspaper work seemed to offer a poor future, so in 1922 he started in the insurance business with the New Mexico Loan and Mortgage Company. On June 22, 1921, Anderson married Henrietta McCartney, and he moved to the Albuquerque, New Mexico. They had two children, Sherburne Presba Anderson and Nancy Anderson. Anderson was soon able to buy the business and change the name to the Clinton P. Anderson Agency, a successful and enduring enterprise. Actively involved in the Rotary Club of Albuquerque since 1919, he was elected to the International Board in 1930 and became president of Rotary International in 1932, a position that introduced him to many business and political contacts.

Anderson returned to public life, becoming chairman of the New Mexico Democratic Party in 1928, and being appointed state treasurer of New Mexico in 1933. That was followed by appointments as director of the Bureau of Revenue, relief administrator for the State of New Mexico, Western States Field Coordinator for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, State Director of the National Youth Administration, chairman of the New Mexico Unemployment Security Division, and Managing Director of the Coronado Cuarto Centennial Commission, among others. It was Anderson's style to take on a newly created position or an emergency situation, organize it, and then leave when he felt that all was running smoothly.

In 1940, a conflict among members of the state Democratic Party resulted in Congressman John J. Dempsey being disqualified from running for another term as New Mexico's only Representative. Party members convinced Anderson to run for the seat, which he won by utilizing his many business and political contacts throughout the state. For the next three decades he divided his time between Albuquerque and Washington.

Anderson became known for his thorough investigative work and during his three terms in the House of Representatives, was assigned to several special committees, including the chairmanship of the Special Committee to Investigate Food Shortages in 1945. The committee argued for a streamlined food distribution system and emphasized long-range planning for increasing food production. It was his success in that assignment, along with their personal friendship, that led to his appointment by Harry Truman as Secretary of Agriculture.[2]

Truman administration

Shortly after Harry S. Truman became President in 1945, he selected Anderson to serve as his Secretary of Agriculture. His most immediate concern was the reorganization of the domestic agricultural economy, which for the previous four years, had been focused on supporting the American war effort in the Second World War. Anderson addressed issues such as price controls, shortages, and subsidies, and he played an important role in developing post-war agricultural policies.

The domestic situation was only one of Anderson's concerns as Secretary of Agriculture. The looming worldwide food crisis, which was becoming more evident by 1946, led President Truman to establish the Famine Emergency Committee.

Anderson made two controversial moves to change the drastic problems. First, utilizing his organizational skills, he incorporated all existing food and agricultural activities under his office. Second, he advised Truman to enlist former President Herbert Hoover to serve as chairman of the Famine Emergency Committee. During this crisis, Anderson, Truman, and Hoover worked together very closely. Many of Hoover's proposals on alleviating the international food shortage were adopted by the Truman administration and it became Anderson's responsibility to implement these proposals. These three men can be credited with preventing an even larger international disaster.

U.S. food production and worldwide distribution was stabilized by 1948 and Anderson decided to retire from the Cabinet. As with every project he had undertaken, Anderson only stayed until he had resolved the problems it faced.

Senate career

Election

Anderson considered retiring altogether after resigning from the cabinet. However, State Democrats, led by the retiring Senator Carl Hatch convinced Anderson to run for Hatch's seat against the formidable and distinguished diplomat Patrick J. Hurley.

These two well-established candidates faced off in one of the most heated campaigns of the 1948 election. Due to the nationwide campaigning of the Truman administration against an 'obstructionist' Republican Congress, Republicans lost across the country, including Hurley.

His re-election in 1954 against former Governor of New Mexico Edwin L. Mechem would be less heated, but more significant due to the Democrats losing the Senate the previous year. But Anderson prevailed and went on to be re-elected by wide margins in 1960 and 1966.

Accomplishments

Anderson's main accomplishment as a Senator was being one of the most outspoken proponents of the space program. He was instrumental in gaining funding for the program while Chair of the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences from 1963-1973. As Chair of the committee during the most active period of space exploration, and the most important time of the Space Race, Anderson held a key policy making role in Washington—not to mention the purse strings for NASA.

Anderson sponsored the final Wilderness bill which passed the Senate by a vote of 73-12 on April 9, 1963, passed the House of Representatives by a vote of 373-1 on July 30, 1964, and was signed into law by President Johnson on September 3, 1964. Richard McArdle, chief of the Forest Service from 1952-1962, remarked, "Without Clinton Anderson there would have been no Wilderness Law."[3] Anderson is also known for the Price-Anderson Nuclear Industries Indemnity Act.

He also served as Chair of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (84th and 86th Congresses), Joint Committee on Construction of Building for Smithsonian (84th-92nd), Joint Committee on Navaho-Hopi Indians (84th-92nd), Special Committee on Preservation of Senate Records (85th and 86th, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs (87th and 88th), Special Committee on National Fuel Policy (87th).

During his tenure, he was admired for accomplishing exactly what he had been doing for much of his life; devoting himself to any cause he thought important. And, even if he knew little on the subject, his determination to fix a problem and to progress society as a whole. Some believed Anderson was a strong possible Democratic Candidate for President in 1968 - something which never materialized due to his age.

The confirmation of Lewis Strauss

In 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Lewis Strauss to serve as Secretary of Commerce. Previously, Mr. Strauss had served in numerous government positions in the administrations of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower. At the time, the 13 previous nominees for this Cabinet position won Senate confirmation in an average of eight days.[4] Because of both personal and professional disagreements, Anderson took up the cause to make sure that Mr. Strauss would not be confirmed by the Senate. Anderson found an ally in Senator Gale W. McGee on the Senate Commerce Committee, which had jurisdiction over Mr. Strauss' confirmation. During and after the Senate hearings, Senator McGee had charged Mr. Strauss with "a brazen attempt to hoodwink" the committee.[4] After 16 days of hearings the Committee recommended Mr. Strauss' confirmation to the full Senate by a vote of 9-8. In preparation for the floor debate on the nomination, the Democratic majority's main argument against the nomination was that Mr. Strauss' statements before the Committee were "sprinkled with half truths and even lies...and that under rough and hostile questioning, [he] can be evasive and quibblesome."[4] Despite an overwhelming Democratic majority, the 86th United States Congress was not able to accomplish much of their agenda since the President had immense popularity and a veto pen.[4] With the 1960 elections nearing, congressional Democrats sought issues on which they could conspicuously oppose the Republican administration. The Strauss nomination proved tailor made.[5]

On June 19, 1959 just after midnight, the Strauss nomination failed by a vote 46-49. At the time, It marked only the eighth time in U.S. history that a Cabinet appointee had failed to be confirmed.[6]

Later life, death and legacy

Due to his age and growing health problems, he retired on January 3, 1973 after serving four terms in the U.S. Senate. Anderson died at his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico in November 1975 from a massive stroke. He is buried at the Fairview Memorial Park in Albuquerque. His wife Henrietta McCartney Anderson died on June 7, 1994, at the age of 94.

In the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, Anderson was played by Mason Adams.

References

- ↑ Ryan, James G.; Leonard C. Schlup (2006). Historical Dictionary of the 1940s. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7656-2107-8.

- ↑ Video: Air Forces Come Home Via Bomber, 1945/05/28 (1945). Universal Newsreel. 1945. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Wilderness.net Clinton Anderson". Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,91771,892639,00.html. Retrieved December 1, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "U.S. Senate: Art & History Home > Historical Minutes > 1941-1963 > Cabinet Nomination Defeated". Senate.gov. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ↑ http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,91771,864640,00.html. Retrieved December 1, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- United States Congress. "Clinton Presba Anderson (id: A000186)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clinton Presba Anderson. |

- Clinton P. Anderson Papers, 1848-1975, University of New Mexico, Center for Southwest Research

- Clinton P. Anderson Papers, 1945-1948, Harry S. Truman Library

- Clinton P. Anderson Photographs, 1946-1975, University of New Mexico, Center for Southwest Research

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John J. Dempsey |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Mexico's at-large congressional district 1941–1945 |

Succeeded by Vacant |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Warren R. Graham, Sr. |

Treasurer of New Mexico 1933–1934 |

Succeeded by James J. Connelly |

| Preceded by Claude R. Wickard |

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Served under: Harry S. Truman 1945–1948 |

Succeeded by Charles F. Brannan |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Carl Hatch |

U.S. Senator (Class 2) from New Mexico 1949–1973 Served alongside: Dennis Chavez, Edwin L. Mechem, Joseph Montoya |

Succeeded by Pete V. Domenici |

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

| Preceded by Sydney W. Pascall |

President of Rotary International 1932–1933 |

Succeeded by John Nelson |