Electric motorsport

|

Nobuhiro Tajima prepares for the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. | |

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Mixed gender | Yes |

| Type | Outdoor |

Electric motorsport (also known as electric racing or electric motor racing) is a category of motor sport that consists of the racing of electric powered vehicles for competition, either in all-electric series, or in open-series against vehicles with different power trains. Very early in the history of automobiles, electric cars held several performance records over internal combustion engine cars, such as land speed records, but fell behind in performance during the first decade of the 20th century. With the renaissance of electric vehicles during the early 21st century, notable electric-only racing series have been developed, for both cars and motorcycles, including for example, the FIA Formula E Championship. In other racing events, electric vehicles are competing alongside combustion engine vehicles, for example in the Isle of Man TT and the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, and in some cases winning outright.

History

Background and early powertrains

see also: History of the steam engine and Origins of the locomotive

Early mechanically powered vehicles used steam power, a technology first developed for static applications (notably, Thomas Newcomen 1712 and James Watt 1765) (see History of the steam engine). Steam for vehicle traction was taken up both for road vehicles and for rail by Richard Trevithick who creating the Puffing devil for transporting passengers by road in 1801, and later rail transport, initially for coal (1804) and then for people (Trevethick 1808, George Stephenson 1824 onwards). By the 1830s steam began to be more widely adopted for transportation, with steam carriages for road (e.g. the 1827 Goldsworthy Gurney Steam bus) and for rail, although the latter quickly became more established for medium and longer distance travel. Mechanically powered road vehicles were largely limited to utilitarian vehicles such as traction engines during this period (especially 1850s onwards, see History of steam road vehicles).

During the 1860s diverse small experiments with personal transportation and different powertrains blossomed, with steam buggies (e.g. Henry Taylor 1867) and even steam motorcycles (Michaex-Perreux and Sylvester Roper, both around 1867-69). Amédée Bollée developed several long distance (Le Mans to Paris, 210 km) steam vehicles from 1873 onwards, including the 1878 La Mancelle of which 50 were produced, and the 1881 La Rapide capable of 62 km/h (39 mph). An early electric powertrain was exhibited in November 1881 by French inventor Gustave Trouvé at the International Exhibition of Electricity in Paris.[1]

English inventor Thomas Parker, who was responsible for innovations such as electrifying the London Underground, overhead tramways in Liverpool and Birmingham, and the smokeless fuel coalite, built the first production electric car in London in 1884, using his own specially designed high-capacity rechargeable batteries.[2] Parker's long-held interest in the construction of more fuel-efficient vehicles led him to experiment with electric vehicles. He also may have been concerned about the malign effects smoke and pollution were having in London.[3]

Early petrol/gasoline-powered internal combustion engine automobiles were completed almost simultaneously by several German inventors working independently: Karl Benz built his first automobile in 1885 in Mannheim. Benz was granted a patent for his automobile on 29 January 1886, and began the first production of automobiles in 1888, after Bertha Benz, his wife, had proved - with the first long-distance trip in August 1888, from Mannheim to Pforzheim and back (194 km) - that the horseless coach was absolutely suitable for daily use.

Overall, there were a variety of powertrains and vehicle forms experimented with during this period, each with different advantages and disadvantages, range, reliability and speed. In terms of outright performance, different powertrains competed for the land speed record through the turn of the 20th century (see below), and it was not until 1924 onwards that internal combustion powertrains began to dominate this aspect.

Early land speed records

The table below details the early history of land speed records from 1898 into the early decades of the 20th century. La Jamais Contente (English: The Never Satisfied) was the first road vehicle to go over 100 kilometres per hour (62 mph). It was an electric vehicle with a light alloy torpedo shaped bodywork and with Fulmen batteries. The vehicle established the land speed record on April 29 or May 1, 1899 at Achères, Yvelines near Paris, France. The vehicle had two direct drive Postel-Vinay 25 kW motors, running at 200 V drawing 124 Amperes each[4][5] for about 68 hp, and was equipped with Michelin tires.

As of 1900, 38% of US automobiles, 33,842 cars, were powered by electricity (40% by steam, and 22% by gasoline).[6] However, as combustion powertrains developed, they offered a superior range than electrics, and (especially after the 1908 Ford Model T, and its mass production from 1913 onwards) a much lower purchase price. In 1912 the electric starter motor was invented by Charles Kettering leading to easier and faster starting of internal combustion powertrains, and removing what had been perceived as one of their main drawbacks (having to use a hand crank). Electric and subsequently steam still had some performance advantages and dominated the outright speed record until 1924. Yet the combustion engine technology benefitted from much greater market penetration and thus more development, and began to achieve greater speed performance than electrics and stream from 1924 onwards.

| Date | Location | Driver | Vehicle | Power | Speed over 1 km |

Speed over 1 mile |

Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | mph | km/h | ||||||

| December 18, 1898 | Achères, Yvelines, France | Jeantaud Duc[7] | Electric | 39.24 | 63.15 | ||||

| December 18, 1898 | Achères, Yvelines, France | Jeantaud Duc | Electric | 57.65 | 92.78 | First specialist land speed record vehicle, first 60 mph pass[8] | |||

| January 17, 1899 | Achères, Yvelines, France | La Jamais Contente | Electric | 65.792 | 105.882 | First man to break a land speed record[7] | |||

| April 13, 1902 | Nice, France Promenade des Anglais | Gardner-Serpollet Œuf de Pâques (Easter Egg) | Steam[8] | 75.06 | 120.80 | ||||

| Aug 5, 1902 | Albis-St. Arnoult, France | Mors | Internal combustion | 76.08 | 122.438 | First IC-powered record[8] | |||

| January 12, 1904 | Lake St. Clair, USA | Ford 999 Racer | Internal combustion | n/a | n/a | 91.37 | 147.05 | On frozen lake[9] (Not recognized by L'Automobile Club de France) | |

| January 26, 1906 | Ormond Beach, USA | Stanley Rocket[10] | Steam | 127.66 | 205.44 | First speed greater than contemporary rail speed record. | |||

| July 12, 1924 | France | FIAT Mephistopheles | Internal combustion | n/a | n/a | 145.89 | 234.98 | Fastest LSR ever on a public road[10] | |

21st century renaissance

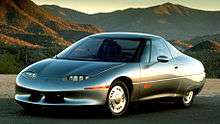

After years out of the limelight, the energy crises of the 1970s and 1980s, and greenhouse gas emission concerns from the late 1980s onwards, brought about renewed interest in electric cars. At the 1990 Los Angeles Auto Show, General Motors President Roger Smith unveiled the GM Impact electric concept car, along with the announcement that GM would build electric cars for sale to the public.

In the early 1990s, the California Air Resources Board (CARB), the government of California's "clean air agency", began a push for more fuel-efficient, lower-emissions vehicles, with the ultimate goal being a move to zero-emissions vehicles such as electric vehicles.[11][12] In response, automakers developed electric models, including the Chrysler TEVan, Ford Ranger EV pickup truck, GM EV1 and S10 EV pickup, Honda EV Plus hatchback, Nissan lithium-battery Altra EV miniwagon and Toyota RAV4 EV.

The automakers were accused of pandering to the wishes of CARB in order to continue to be allowed to sell cars in the lucrative Californian market, while failing to adequately promote their electric vehicles in order to create the impression that the consumers were not interested in the cars, all the while joining oil industry lobbyists in vigorously protesting CARB's mandate.[12] GM's program came under particular scrutiny; in an unusual move, consumers were not allowed to purchase EV1s, but were instead asked to sign closed-end leases, meaning that the cars had to be returned to GM at the end of the lease period, with no option to purchase, despite lessor interest in continuing to own the cars.[12] Chrysler, Toyota, and a group of GM dealers sued CARB in Federal court, leading to the eventual neutering of CARB's ZEV Mandate.

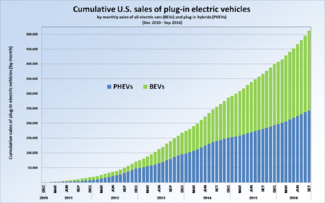

Partly due to the incumbent manufacturers demonstrating an apparent lack of will to offer alternatives to combustion engine powertrains, the early 21st century has seen much of the impetus to develop automotive electric powertrains come from independents, enthusiasts and creative tinkerers willing think outside the box. Early examples include the 1995 Solectria Sunrise and the 1997 AC Propulsion tzero a handmade electric sportscar which was itself produced in very limited numbers but whose impressive powertrain was used by many others, including Tesla motors, Mini and Venturi. Tesla in turn, producing several thousand of its roadster sportscar from 2008 onwards, played a large part in changing the public and industry perception of electric cars, and goaded other manufacturers to take electric cars seriously once more. Bob Lutz famously credited Tesla as providing the impetus for the Chevrolet volt. Japan's TEPCO also worked with Mitsubishi and Subaru around this time to develop electric cars, including the Mitsubishi i-MiEV. Such moves, combined with increasing pressure from regulators has led to larger manufacturers developing electric powered vehicles for sale once more from around 2010 onwards (see List of production battery electric vehicles).

The emergence of higher volume manufacturing of electric powertrain vehicles has allowed for economies of scale and increased research and development of electrical batteries, the critical technology in electric powertrains. Battery power density (the amount of energy stored per unit weight) has typically been the greatest drawback of electric powertrains in comparison to gasoline combustion engine powertrains. Steady advances in battery technology, especially lithium-ion battery technologies first commercialized in the early 1990s (see e.g. Research in lithium-ion batteries) have driven innovations in electric powertrains, and further battery advances allow them to once again compete with the combustion engine powertrains in motorsports events.

Open-category series

Pikes Peak International Hill Climb

The Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, also known as The Race to the Clouds, is an annual automobile and motorcycle hillclimb to the summit of Pikes Peak in Colorado, USA. The track measures 12.42 miles (19.99 km) over 156 turns, climbing 4,720 ft (1,440 m) from the start at Mile 7 on Pikes Peak Highway, to the finish at 14,110 ft (4,300 m), on grades averaging 7.2%.[16]

The race is self sanctioned and has taken place since 1916, making it the second oldest motorsport event in the Western Hemisphere behind the Indianapolis 500.[16] It is currently contested by a variety of classes of cars, trucks, motorcycles and quads. There are often numerous new classes tried and discarded year-to-year. In the modern era, electric vehicles have competed in the event since 1983 (Joe Balls, Sears Electric car). In the 2-wheeled divisions, the electric powertrains are already able to outcompete the combustion engines; the 2013 overall winner was an electric bike, the Lightning Motorcycle LS-218 electric Superbike ridden by Carlin Dunne in a time of 10:00.694, a new course record for the 2-wheeled class.

In the 4-Wheeled Divisions, the results of recent years show that the relative improvements in race time are advancing at different rates in the electric classes compared to the unlimited/combustion engine classes. Unlimited class vehicles, with combustion engines, broke the 16 minute barrier in 1938, and have steadily improved over the subsequent decades, breaking the 10-minute barrier in 2011.[17] Meanwhile the electric vehicle class broke the 16 minute barrier in 1994 (Katy Endicott, Honda Civic Shuttle finishing in 15:44:71), and the 10-minute barrier in 2013 (Nabuhiro 'Monster' Tajima, E-Runner finishing in 9:46:53).[17] In the 2014 event, the Mitsubishi team (MiEV Evolution III) achieved 2nd (Greg Tracey, 9:08.188) and 3rd position (Hiroshi Masuoka, 9:12:204) - within 3 seconds and 7 seconds (respectively) of the overall fastest vehicle, a gasoline powered Norma race car.[18] The graph to the right shows the relative rates of improvement of these two classes since the 1980s.

2015 for the first time in the history of the race was an electric car to win the race outright. The winning car was the Latvian team Drive eO's 3rd generation vehicle, eO PP03 with peak power of 1020 kW and peak torque of 2160 Nm, weighing 1200 kg. The time achieved was 9:07.222, just faster than Greg Tracey's 9:08.188 time in 2014. Second place was also earned by an electric car, the Tajima Rimac Automobili E-Runner Concept_One with peak power of 1100 kW, peak torque of 1500 Nm, and weighing 1500 kg.[19]

The winning driver Rhys Millen said in an interview that the vehicle had lost half its tractive power (due to heat) from around the half way point. Based on testing the team had expected a run 30 seconds faster.[20]

Both the two above teams and drivers raced again in 2016, with evolutions of the vehicles, and were joined by a prototype '4-motor EV' from Acura based on the 2016 NSX production car, with heavy modifications to all-electric drive. The Acura, driven by Tetsuya Yamano, achieved a remarkable time for its first outing, finishing in 9:06:015, and third place overall. Drive eO's 4th generation vehicle, eO PP100 achieved a time of 8:57:118, improving on the previous year's time and coming second overall. The winning 2016 vehicle was a combustion engine Norma driven by Romain Dumas with a time 8:51:445. The Norma has similar power to weight ratio to the PP100, but weighs half as much and as a result has better traction in corners. Dumas' team also won in an earlier version of the same vehicle in 2014 with a time of 9:05:801, thus improving by some 14 seconds over 2 years technological evolution. The Drive eO vehicle improved by some 10 seconds in one year, over its 2015 time.

Isle of Man TT

TT Zero is part of the Isle of Man TT and races for 1 lap (37.733 miles) of the Snaefell Mountain Course. The TT Zero event as an officially sanctioned Isle of Man TT race is for racing motorcycles where "The technical concept is for motorcycles (two wheeled) to be powered without the use of carbon based fuels and have zero toxic/noxious emissions."[21]

The inaugural 2010 TT Zero race was won by Mark Miller riding a MotoCzysz E1pc motor-cycle in 23 minutes and 22.89 seconds at an average race speed of 96.820 mph for 1 lap (37.733 miles) of the Mountain Course and the first United States winner since Dave Roper won the 1984 Historic TT riding a 500cc Matchless. The TT Zero race replaced the TTXGP franchise with the simplification of the regulations[22] and the emphasis on electric powered motor-cycles.[23] The MotoCzysz E1pc was also the first American manufactured motor-cycle to win an Isle of Man TT Race since Oliver Godfrey won the 1911 Senior TT with an Indian V-Twin motor-cycle.

The riders of the TT Zero bikes are typically those that also compete in the combustion engine classes and are very experienced on the circuit. Comparing the experience of the different powertrains, Lee Johnston said as he climbed off his electric bike in the 2015 practice sessions: “That was just mint. It feels so stable, it’s unbelievable. It’s just so peaceful. No revving.” Asked for what was memorable, he responded “I think just the peace and quiet and riding over the mountain, no noise and seeing the sunset..."[24]

Fastest race lap by year

(practice & qualifying session laps not included)

| Year | Rider(s) | Machine | Lap time | Average speed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||

| 2010 | Mark Miller | MotoCzysz E1pc / MotoCzysz | 23:22:89 | 96.820 | 155.817 |

| 2011 | Michael Rutter | MotoCzysz | 22:43:68 | 99.604 | 160.297 |

| 2012 | Michael Rutter | MotoCzysz | 21:45:33 | 104.056 | 167.462 |

| 2013 | Michael Rutter | MotoCzysz | 20:38:461 | 109.675 | 176.505 |

| 2014 | John McGuinness | Honda Shinden San / Team Mugen | 19:17:300 | 117.366 | 188.882 |

| 2015 | John McGuinness | Honda Shinden Yon / Team Mugen | 18:58:743 | 119.279 | 191.961 |

The TT Zero lap speeds have been improving at an average rate of around 4 mph each year since the series began (119.279 mph as of 2015). With more mature technology, the combustion engine bikes' lap speeds in the mainstream TT have been improving at a lower rate of around 0.4 mph each year in recent years (132.298 mph as of 2014). If these trends continue, the TT Zero bikes may match the combustion engine bikes by 2018 or 2019, and exceed them thereafter.

FIA World Endurance Championship

The FIA World Endurance Championship is an auto racing world championship organized by the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) and sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The series usurps the ACO's former Intercontinental Le Mans Cup which began in 2010, and is the first endurance series of world championship status since the demise of the World Sportscar Championship at the end of 1992. The World Endurance Championship name was previously used by the FIA from 1981 to 1985.

The series feature multiple classes of cars competing in endurance races, with sports prototypes competing in the Le Mans Prototype categories, and production-based grand tourers competing in the LM GTE categories. World champion titles are awarded to the top scoring manufacturers and drivers over the season,[25][26] while other cups and trophies will be awarded for drivers and private teams.[27]

The ZEOD RC is designed by Ben Bowlby, who previously designed the 2012 Garage 56 entry DeltaWing as an employee for DeltaWing Project 56 LLC, a consortium led by Don Panoz. He previously worked for DeltaWing LLC, a Chip Ganassi company created to develop a DeltaWing concept race car for IndyCar. Nissan provided an engine and received naming rights on the Garage 56 entry at the 2012 Le Mans race, as well as and other 2012 American Le Mans Series races

The ZEOD RC will utilize a hybrid electric drivetrain with lithium ion battery packs in a chassis similar in design to the DeltaWing.[28] In a June 22, 2013 article at Autosport.com, Bowlby said: "This is a new car, but it uses the narrow track technology of the DeltaWing and that gives us great efficiency. It is something we understand and it is an efficient way of getting around Le Mans."

At the 2014 24 Hours of Le Mans, the ZEOD RC's first race, the car had to retire during the race's early hours due to a gearbox failure. However it managed to achieve its goals of reaching a speed above 300 km/h and completing a lap in Le Mans using electric power only.

All-electric series

Formula E

Formula E is a class of auto racing, sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), and is the highest class of competition for one-make, single-seater, electrically powered racing cars.[29] The series was conceived in 2012, and the inaugural championship started in Beijing in September 2014.[30]

For the first season, all teams were supplied an electric racing car built by Spark Racing Technology, called the Spark-Renault SRT 01E. The chassis was designed by Dallara, with an electric motor developed by McLaren (the same as that used in its P1 supercar), a battery system created by Williams Advanced Engineering and a Hewland five-speed gearbox. Since the second season regulations allow for new powertrain manufacturers. The manufacturers are able to build the electric motor, inverter, gearbox and cooling system. The chassis and battery stay the same.

A Formula E car has a power of at least 186 kW (250 hp). The car is able to accelerate from 0–100 km/h (0–62 mph) in 3 seconds, with a maximum speed of 225 km/h (140 mph).[31] The noise levels are approximately 80 dB (SPL), which is more than an average petrol car which produces about 70 dB.[32] The generators used to re-charge the batteries are powered by glycerine, a by-product of bio-diesel production.[33]

Electric GT

A series with all-electric GT cars (in the first season all Tesla Model S), called Electric GT (EGT) is planned to start in 2017.

Andros Trophy

The Andros Trophy, a French ice racing series, began experimenting with electric cars in 2007. An electric car class was added in 2010. The car, developed by Exagon, features a 67 kW engine and a total weight of 800 kg.

World Solar Challenge

The World Solar Challenge is a biennial solar-powered car race which covers 3,021 km (1,877 mi) through the Australian Outback, from Darwin, Northern Territory to Adelaide, South Australia.

The race attracts teams from around the world, most of which are fielded by universities or corporations although some are fielded by high schools. The race has a 28-year history spanning twelve races, with the inaugural event taking place in 1987.

Rallycross

American-based Global Rallycross Championship announced that an electric class will be added for the 2018 season.

Future prospects

Electric powertrains have advantages over combustion engines in power delivery and vehicle dynamics (especially on motorbikes), but still have range disadvantages in longer races (note that combustion engine vehicle often have to refill energy supply also, e.g. Isle of Man TT bikes refill every two laps). Early electric challengers to combustion engine vehicles are therefore typically in shorter more intensive races such as hill climbs or other limited distance races, or simply in fastest lap times (e.g. around the Isle of Man Snaefell circuit). Nevertheless, for endurance racing, hybrid electric powertrains have also proven their advantages of pure combustion engine powertrains, with recent years at the 24 Hours of Le Mans all won by the hybrid electric Audi R18 e-tron quattro.

See also

Environmentalism in motorsport

References

- ↑ Wakefield, Ernest H. (1994), History of the Electric Automobile, Society of Automotive Engineers, pp. 2–3, ISBN 1-56091-299-5

- ↑ "World's first electric car built by Victorian inventor in 1884". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ↑ Fuller, John (9 April 2009). "What is the history of electric cars?". auto.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ "La Jamais Contente" (PDF).

- ↑ "EV Zero?". EV1 Club. Archived from the original on 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ↑ Zachary Shahan. "The Evolution of Electric Cars". Sustainnovate. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Northey, Tom (1974). "Land Speed Record: The Fastest Men on Earth". In Ian Ward. World of Automobiles. Vol. 10. London: Orbis. p. 1161-65

- 1 2 3 Northey, p. 1162.

- ↑ Cars Against the Clock, The World Land Speed Record, Robert B. Jackson (New York, Henry Z. Walck, Inc.), p.19, ISBN 0-8098-2078-1

- 1 2 Northey, p.1163.

- ↑ Sperling, Daniel and Deborah Gordon (2009), Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 24 and 189–191, ISBN 978-0-19-537664-7

- 1 2 3 Who Killed the Electric Car? Directed by Chris Paine, Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics

- ↑ Cobb, Jeff (2016-09-01). "Americans Buy Their Half-Millionth Plug-in Car". HybridCars.com. Retrieved 2016-09-02. See other figures in graphs.

- ↑ Electric Drive Transportation Association (EDTA) (October 2016). "Electric Drive Sales Dashboard". EDTA. Retrieved 2016-10-19. Sales figures sourced from HybridCars.com and direct reports submitted by EDTA member companies

- ↑ HybridCars.com and Baum & Associates. "HybridCars Dashboard". HybridCars.com. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- 1 2 PPIHC race overview, http://www.ppihc.com/2014-spectator-guide/

- 1 2 "Race winners by year". Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ http://livetiming.net/ppihc/?Class=. North Country Timing & Scoring and LiveTiming.net http://livetiming.net/ppihc/?Class=. Retrieved 30 June 2014. Missing or empty

|title=(help); External link in|website=(help) - ↑ Biesbrouck, Tim (1 June 2015). "Tajima and Rimac reveal 1100kW electric Pikes Peak racer + photos and specs". Electric Autosport. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ Rhys Millen Wins Pikes Peak First Electric Car Victory. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ REGULATIONS TT ZERO – 2010 International Tourist Trophy – Isle of Man 29 May – 11 June p27 ACU Events Ltd (2010)

- ↑ Isle of Man Tourist Trophy Races – Official Programme May 29–11 June 2010 page 14 Isle of Man Department of Community, Culture & Leisure – ACU Events Ltd (2010) Mannin Media Group Ltd

- ↑ REGULATIONS TT ZERO – 2010 International Tourist Trophy – Isle of Man 29 May – 11 June Appendix C page 25–27 ACU Events Ltd (2010)

- ↑ "Victory Racing Breaks the 100mph Average Lap Speed Barrier on its First TT Practice Session". Cycle World. US. 6 June 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ "2012 FIA World Endurance Championship". fia.com. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 2011-06-03. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ "World Motor Sport Council". fia.com. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 2011-06-03. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ "The FIA World Endurance Championship is unveiled!". lemans.org. Automobile Club de l'Ouest. 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ↑ O'Leary, Jamie (21 June 2013). "Nissan unveils electric Le Mans Garage 56 car". Autosport.com. Haymarket Press. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ "FIA Formula E Championship". fia.com.

- ↑ Telegraph Sport (13 September 2014). "Formula E opens with spectacular crash involving Nick Heidfeld and Nicolas Prost as Lucas di Grassi claims win". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ "Guide to – Car – Specifications". FIA Formula E. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ↑ "Guide to – Car – Sound". FIA Formula E. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ↑ "Formula E uses pollution-free glycerine to charge cars". FIA Formula E. 2014-09-13. Retrieved 2016-10-29.