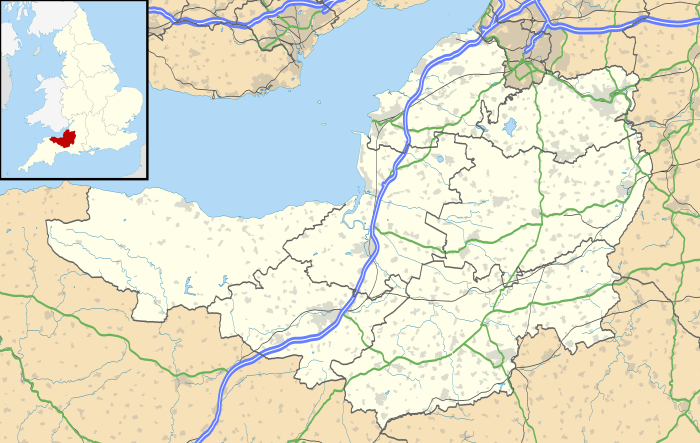

Chard, Somerset

Coordinates: 50°52′22″N 2°57′31″W / 50.8728°N 2.9587°W

Chard is a town and a civil parish in the English county of Somerset. It lies on the A30 road near the Devon border, 15 miles (24 km) south west of Yeovil. The parish has a population of approximately 13,000 and, at an elevation of 121 metres (397 ft), Chard is the southernmost and one of the highest towns in Somerset. Administratively Chard forms part of the district of South Somerset.

The name of the town was Cerden in 1065 and Cerdre in the Domesday Book of 1086. After the Norman Conquest, Chard was held by the Bishop of Wells. The town's first charter was from King John in 1234. Most of the town was destroyed by fire in 1577, and it was further damaged during the English Civil War. A 1663 will by Richard Harvey of Exeter established Almshouses known as Harvey's Hospital. In 1685 Chard was one of the towns in which Judge Jeffreys held some of the Bloody Assizes after the failure of the Monmouth Rebellion.

Textile manufacture was important to the town during the Middle Ages. Chard is the birthplace of powered flight as in 1848 John Stringfellow first demonstrated that engine-powered flight was possible. Percy and Ernist Petter, who formed Westland Aircraft Works, witnessed some of Stringfellow's demonstrations in Chard and often asked for help in the formation of Westland's first aircraft development factory on the outskirts of Yeovil. AgustaWestland now holds the Henson and Stringfellow lecture yearly for the RAeS.[2][3] James Gillingham developed articulated artificial limbs. Chard is a key point on the Taunton Stop Line, a World War II defensive line.

The Chard Canal was a tub boat canal built between 1835 and 1842. Chard Branch Line was created in 1860 to connect the two London and South Western Railway and Bristol and Exeter Railway main lines and ran through Chard until 1965.

Local folklore relates that the town has a very unusual and unique feature: a stream running along either side of Fore Street. One stream eventually flows into the Bristol Channel and the other reaches the English Channel. Chard Reservoir, approximately a mile north east of the town, is a Local Nature Reserve, and Snowdon Hill Quarry a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest. Major employers in the town include Numatic International Limited and the Oscar Mayer food processing plant. There are a range of sporting and cultural facilities, with secondary education being provided at Holyrood Academy; religious sites including the Church of St Mary the Virgin which dates from the late 11th century.

History

Chard's name was Cerden in 1065 and Cerdre in the Domesday Book of 1086 and it means "house on the chart or rough ground" (Old English: ćeart + renn).[4] Before the Norman Conquest Chard was held by the Bishop of Wells.[5] The town's first charter was from King John and another from the bishop in 1234, which delimited the town and laid out burgage holdings in 1-acre (4,000 m2) lots at a rent of twelve pence per year.[6] The parish of Chard was part of the Kingsbury Hundred,[7]

Most of the town was destroyed by fire in 1577.[5][8] After this time the town was largely rebuilt including Waterloo House and Manor Court House in Fore Street which were built as a house and courtroom, and have now been converted into shops and offices.[9] Further damage to the town took place during the English Civil War with both sides plundering its resources, particularly in 1644 when Charles I spent a week in the town.[5]

A 1663 will by Richard Harvey of Exeter established Almshouses which became Harvey's Hospital. These were rebuilt in 1870 largely of stone from previous building.[5][10] In 1685 Chard was one of the towns in which Judge Jeffreys held some of the Bloody Assizes after the failure of the Monmouth Rebellion in which 160 men from Chard joined the forces of the Duke of Monmouth. The subsequent hangings took place on Snowden Hill to the west of the town.[5] As elsewhere in this area, the 'finger-post' road-sign at this spot is painted red and is known as 'Red Post' to commemorate the executions.

There was a fulling mill in the town by 1394 for the textile industry.[5] After 1820 this expanded with the town becoming a centre for lace manufacture led by manufacturers who fled from the Luddite resistance they had faced in the English Midlands. Bowden's Old Lace Factory[11] and the Gifford Fox factory[12] are examples of the sites constructed. The Guildhall was built as a Corn Exchange and Guildhall in 1834 and is now the Town Hall.[13]

On Snowdon Hill is a small cottage which was originally a toll house built by the Chard Turnpike trust in the 1830s,[14] to collect fees from those using a road up the hill which avoided the steep gradient.[15]

Chard claims to be the birthplace of powered flight, as it was here in 1848 that the Victorian aeronautical pioneer John Stringfellow (1799–1883) first demonstrated that engine-powered flight was possible through his work on the Aerial Steam Carriage.[2][3] James Gillingham (1839–1924) from Chard pioneered the development of articulated artificial limbs when he produced a prosthesis for a man who lost his arm in a cannon accident in 1863.[3] Chard Museum has a display of Gillingham's work.[16]

Chard was a key point on the Taunton Stop Line, a World War II defensive line consisting of pillboxes and anti-tank obstacles, which runs from Axminster north to the Somerset coast near Highbridge.[17] In 1938 a bomb proof bunker was built behind the branch of the Westminster Bank. During the war it was used to hold duplicate copies of the bank records in case its headquarters in London was destroyed. It was also used to store the emergency bank note supply of the Bank of England. There has also been speculation that the Crown Jewels were also stored there, however this has never been confirmed.[18]

Action Aid, the International Development Charity, had their headquarters in Chard when they started life in 1972 as Action in Distress. The Supporters Services department of the charity is still based in Chard.[19]

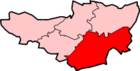

Governance

Chard was one of the boroughs reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, and remained a municipal borough known as Chard Municipal Borough.[20] until the Local Government Act 1972, when it became a successor parish in the Non-metropolitan district of South Somerset.

The town council (a parish council with the status of a town) has responsibility for local issues, including setting an annual precept (local rate) to cover the council's operating costs and producing annual accounts for public scrutiny. The town council evaluates local planning applications and works with the local police, district council officers, and neighbourhood watch groups on matters of crime, security, and traffic; their role also includes initiating projects for the maintenance and repair of parish facilities, as well as consulting with the district council on the maintenance, repair, and improvement of highways, drainage, footpaths, public transport, and street cleaning. Conservation matters (including trees and listed buildings) and environmental issues are also the responsibility of the council. The town council has a reception and offices in the guildhall.[21] The building was built in 1834 as a corn exchange, replacing an earlier 16th-century building that used to be situated perpendicular to where the current road is in the high street outside the Phoenix Hotel, a dig of the high street back in the late 1980s revealed the original footprint of the old guildhall. The new re-modeled Guildhall is a Grade II* listed building.[22]

In 2006 Chard Town Council came to the attention of the National Press when Mayor Tony Prior was found guilty of sexual discrimination and victimisation of the Town Clerk. He was ordered to pay £33,000 in compensation and banned from holding public office for nine months.[23]

The South Somerset district council is responsible for local planning and building control, local roads, council housing, environmental health, markets and fairs, refuse collection and recycling, cemeteries and crematoria, leisure services, parks, and tourism. Somerset County Council is responsible for running the largest and most expensive local services such as education, social services, the library, roads, public transport, trading standards, waste disposal and strategic planning, although fire, police and ambulance services are provided jointly with other authorities through the Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service, Avon and Somerset Constabulary and the South Western Ambulance Service.

The civil parish of Chard Town (its formal name) contains exactly five electoral wards — Avishayes, Coome, Crimchard, Holyrood, and Jocelyn.

Chard is also part of the Yeovil county constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election, and part of the South West England constituency of the European Parliament which elects six MEPs using the d'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation.

Twinnings

Chard is twinned with Helmstedt in Germany (since 12 April 1980), Morangis in France (since 29 May 1994) and also Şeica Mare in Transylvania, Romania.[24]

Geography

At an altitude of 121 metres (397 ft), Chard is the highest town in Somerset, and is also the southernmost.[17] The suburbs include: Crimchard, Furnham, Glynswood, Henson Park and Old Town. Local folklore claims that the town has a very unusual and unique feature, a stream running along either side of Fore Street. One stream eventually flows into the Bristol Channel and the other reaches the English Channel.[25] This situation changed when the tributary of the Axe was diverted into the Isle; the gutter in Holyrood Street, though, still flows into the River Axe and therefore it is still true it lies on the watershed and that two gutters within the down eventually drain into the Bristol Channel and the English Channel.[26]

The 36.97 hectares (91.4 acres) Chard Reservoir, around a mile northeast of the town, is a Local Nature Reserve. It is used for dog walking, fishing and birdwatching, with a bird hide having been installed.[27] Species which are spotted regularly include herons, kingfishers, cormorants, grebes, ducks and also a wide range of woodland songbirds. Others include the great white egret, cattle egret, and spotted redshank.[28]

Snowdon Hill Quarry is a 0.6 hectare (1.3 acre) geological Site of Special Scientific Interest on the western outskirts. The site shows rock exposures through the Upper Greensand and Chalk, containing fossil crustaceans which are both unique and exceptionally well-preserved making it a key locality for the study of palaeontology in Britain. The unit has been dated to the subdivision of the Chalk known as the Turrilites acutus Zone, named after one of the characteristic fossils,[29] which was laid down in the Middle Cenomanian era between 99.6 ± 0.9 MA and 93.5 ± 0.8 MA (million years ago).

There are also caves in Chard, first recorded in a charter of 1235 as being used by stonemasons, which provided local building stone. The cave is smaller than when it was used as a quarry as part of the roof has fallen in but a cave 20 feet (6.1 m) below ground still exists with the remains of the supporting pillars left when it was being worked.[26]

Climate

Along with the rest of South West England, Chard has a temperate climate which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of the country.[30] The annual mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50.0 °F). Seasonal temperature variation is less extreme than most of the United Kingdom because of the adjacent sea temperatures. The summer months of July and August are the warmest with mean daily maxima of approximately 21 °C (69.8 °F). In winter mean minimum temperatures of 1 °C (33.8 °F) or 2 °C (35.6 °F) are common.[30] In the summer the Azores high pressure affects the south-west of England, however convective cloud sometimes forms inland, reducing the number of hours of sunshine. Annual sunshine rates are slightly less than the regional average of 1,600 hours.[30] In December 1998 there were 20 days without sun recorded at Yeovilton. Most the rainfall in the south-west is caused by Atlantic depressions or by convection. Most of the rainfall in autumn and winter is caused by the Atlantic depressions, which is when they are most active. In summer, a large proportion of the rainfall is caused by sun heating the ground leading to convection and to showers and thunderstorms. Average rainfall is around 700 mm (28 in). About 8–15 days of snowfall is typical. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, and June to August have the lightest winds. The predominant wind direction is from the south-west.[30]

Economy

Chard is the home of Numatic International Limited, notable for its 'Henry' vacuum cleaners. The company employs over 700 people. In contrast to competitors such as Hoover and Dyson the firm continues to manufacture in Britain. The site occupies an area of more than 10 hectares and operates continuously, producing over 4,000 products per day.

One of the other large employers in Chard is Oscar Mayer, which is not to be confused with the American company of the same name owned by Kraft Foods. In 2007, it was announced that the factory would be bought by Icelandic company, the Alfesca Group which owns Lyons seafoods.[31] However this deal fell through and the company announced 250 job losses.[32][33] Oscar Mayer has historically employed many Portuguese and, more recently, Polish workers.[31]

Chard is also home to Brecknell Willis & Co. Ltd., one of the world's oldest and leading specialists in the design, construction, and installation of railway electrification systems, most notably metro and light rail systems. Its largest customer, London Underground, purchases both train born equipment and infrastructure. Brecknell Willis occupies a site at the bottom of the hill, next to the site of the old LSWR station, which is now a Tesco store. At the time of writing (August 2014) the company was preparing to move into a new purpose-built building from which all of its operations will be based. In early July 2014 the company was bought by WABTEC, bringing it into the Wabtec Rail Group as well as the Falstand Electric Group.

Transport

From 1842 Chard was the terminus of the Chard Canal, a tub boat canal that joined the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal at Creech St. Michael. It had four aqueducts, three tunnels and four inclined planes along its 13.5-mile (21.7 km) length. It took seven years to construct and cost about £140,000 (£11.9 million in 2015).[34][35][36]

In the 1860s the town became the terminus of two railway lines. The first was opened in 1863 by the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) as a short branch line from their main line. This approached the town from the south.[37] The second and longer line was opened by the Bristol and Exeter Railway (B&ER) in 1866 and ran northwards, close to the route of the canal, to join their main line near Taunton.[38] From 1917 they were both operated by one company, but services were mostly advertised as though it was still two separate lines.[39] It was closed to passengers in 1962 and freight traffic was withdrawn a few years later.[40]

The LSWR's station (later known as Chard Town) opened in 1860 with a single platform, and the B&ER's (variously known as Chard Joint or Chard Central) in 1866. For five years LSWR trains continued to call at Chard Town and then reversed to the connecting line and then resumed their forward journey to the Joint station. In 1871 a new platform was opened on the connecting line; this closed to passengers on 1 January 1917 but the town station was the main goods depot for the town until it finally closed on 18 April 1966. Passenger trains ceased to operate to Chard Central on 11 September 1962, and private goods traffic on 3 October 1966. The station building and train shed still stand and are in use by engineering companies.[40]

The town's public transport links to Taunton are now provided by First South West (bus route 30)[41] and Stagecoach Southwest (bus route 99),[42] which both run hourly during weekdays.

Sport

Chard has a number of local sport clubs. Chard Town F.C. play football in the Western Football League,[43] whilst a number of Chard football clubs play in the Perry Street and District League.[44] The Rugby union club, Chard RFC, was formed in 1876.[45] The Club runs 3 Senior sides, with the 1stXV playing currently in South West One (west) achieving promotion to National League 3 South West on 26 April 2014 beating Old Towcestrians in the playoff final.[46] Chard Hockey Club was established in 1907 and it now runs three male and three female sides.[47] There are also facilities for cricket, tennis, bowls, and golf.[48] The Wessex Pool League is also played in a number of Pubs in Chard. Resident Sports Photographer, and Vice Chair of Chard Camera Club, Peter O'Shea QIS LRPS TMIET,[49] often captures the many sports leagues in and around the Chard area, and has had work published in the Chard and Ilminster News, Sunday Independent Newspaper and Photographic Magazines.

Education

The original school building in Fore Street was built in 1583 a private residence for William Symes of Poundisford. In 1671 his youngest son, John, conveyed the property to 12 trustees so that it should be converted into a grammar school - according to his father's wish.[50]

Avishayes Community Primary School, Manor Court Community Primary School, Tatworth Primary School and The Redstart Primary School all offer primary education, while Holyrood Academy offers secondary education. The school, which has specialist Technology college status, has 1,226 pupils between the ages of 11 and 18.[51]

Religious sites

The Anglican Church of St Mary the Virgin dates from the late 11th century and was rebuilt in the 15th century. The tower contains eight bells, of which two were made in the 1790s by Thomas Bilbie of the Bilbie family in Cullompton.[52] The three-stage tower has moulded string courses and an angle stair turret in the north-west corner. The church has been designated by English Heritage as a grade I listed building.[53] There is a church room, built in 1827.[54] The Baptist Church in Holyrood Street was built in 1842.[55]

Notable residents

It was the residence of William Samuel Henson, aviation engineer and inventor, who worked with fellow Chard resident John Stringfellow to achieve the first powered flight, in 1848, in a disused lace factory, with a 10 foot (3 m) steam-driven flying machine.[56][57] It was the birthplace of James Gillingham who pioneered the development of articulated artificial limbs[3][16] and of Corporal Samuel Vickery who was awarded the VC in 1897 for his actions during the attack on the Dargai Heights, Tirah, India during the Tirah Campaign.[58] Margaret Bondfield, a Labour politician and feminist and the first woman Cabinet minister in the United Kingdom was born in Chard in 1873.[59] Dr Andrew Wright, discoverer of ancient mountain ranges and fjord landscapes underneath the Antarctic ice cap, spent most of his childhood in Chard where he attended the local school.[60] J.W. Gifford F.R.A.S, the prominent Chard Lace Mill owner was a noted astronomer, scientist and was the second person in the world to produce an X-ray picture (as a result of his interests in photography also), publishing his works in the Royal Photographic Society's Journal in 1895. He was known locally as the "optical man" due to his work with optics and telescopes. In addition, Dr P Denner MB ChB (Birmingham 1979) DRCOG DCH MRCGP of Essex House Medical Centre in the High Street, Mr. D.J. Hartland CEng, MIMechE, MIEE, Chief and Senior Projects Engineer for Brecknell Willis & Co Ltd.[61] Chard cave explorers Dr. Peter Glanvill and Nigel Cox were co-discoverers of the largest cave chamber so far found in the UK, the Frozen Deep in Cheddar Gorge, in 2012.[62]

See also

References

- ↑ "Statistics for Wards, LSOAs and Parishes — SUMMARY Profiles" (Excel). Somerset Intelligence. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- 1 2 Day, Lance; McNeil, Ian (1998). Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology. Taylor & Francis. p. 678. ISBN 0-415-19399-0.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chard was there first". Daily Telegraph. 7 October 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ↑ Watts, Victor (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-names (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-521-16855-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bush, Robin (1994). Somerset: The complete guide. Wimbourne: Dovecote Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 1-874336-26-1.

- ↑ Havinden, Michael. The Somerset Landscape. The making of the English landscape. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 114. ISBN 0-340-20116-9.

- ↑ "Somerset Hundreds". GENUKI. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Leete-Hodge, Lornie (1985). Curiosities of Somerset. Bodmin: Bossiney Books. p. 93. ISBN 0-906456-98-3.

- ↑ "Waterloo House and Manor Court House". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Harvey's Hospital and attached rear boundary walls to east and west". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Bowden's Old Lace Factory". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Factory Building,formerly of Gifford Fox and Company Limited". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "The Guildhall". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Snowdon Turnpike Cottage". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Warren, Derrick (2005). Curious Somerset. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-7509-4057-3.

- 1 2 "Pioneers in Artificial Limbs". Chard Museum. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Welcome to Chard". Chard Town Council. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ Warren, Derrick (2005). Curious Somerset. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-7509-4057-3.

- ↑ "Fundraising FAQ". Action Aid. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ "Chard RD". A vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "Reception office". Chard Town Council. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "The Guildhall". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ↑ Savill, Richard (7 October 2006). "Mayor pays £33,000 for his 'sexual thrill'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ↑ Maclagan, Kirsty (31 August 2009). "Mayor forges links with Romanian town". Chard & Ilminister News. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ "South Somerset's Market Towns" (PDF). Visit Somerset. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- 1 2 Warren, Derrick (2005). Curious Somerset. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-7509-4057-3.

- ↑ "Chard Reservoir Nature Reserve". Chard Reservoir Nature Reserve. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Chard Reservoir". South Somerset Council. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "SSSI citation sheet for Snowden Hill Quarry" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "South West England: climate". Met Office. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- 1 2 Rudkin, Jess (3 July 2008). "Behind the headlines: Why Oscar Mayer had to lose 250 staff". BBC. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ "Jobs fears at Oscar Mayer". Chard & Ilminster News. This is the West Country. 27 June 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ "Shadow falls on the future of Oscar Mayer Chard factory as jobs are axed". Food Manufacture.co.uk. 29 July 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Lost canals of England and Wales Ronald Russell page 68 ISBN 0-7153-5417-5

- ↑ Dunning, Robert (1983). A History of Somerset. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. pp. 99–102. ISBN 0-85033-461-6.

- ↑ Somerset County Council archives: Canals and Canal Projects. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ↑ Phillips, Derek; Pryer, George (1997). The Salisbury to Exeter Line. Sparkford: Oxford Publishing Company. p. 111. ISBN 0-86093-525-6.

- ↑ MacDermot, E T (1931). "The Bristol and Exeter Railway". History of the Great Western Railway, volume II 1863–1921. London: Great Western Railway.

- ↑ Time Tables. London: Great Western Railway. 4 October 1920. p. 73.

- 1 2 Oakley, Mike (2006). Somerset Railway Stations. Bristol: Redcliffe Press. pp. 36–39. ISBN 1-904537-54-5.

- ↑ "Timetables". Bristol, Bath and the West. First Group. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ↑ "Taunton, Chard ... Yeovil". Timetables. Stagecoach Bus. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ "Chard Town FC". Web Teams. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Perry Street & District League". TheFA.com. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ "Chard Rugby Club". Pitchero. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Rugby: Chard clinch national league status". Chard and Ilminster News. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "Chard Hockey Club". Chard Hockey Club. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Local attractions". Chard Town Council. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Resident Sports Photographer Peter O'Shea QIS LRPS TMIET Website".

- ↑ "Chard School". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Holyrood Community School". Ofsted. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ↑ Moore, James; Rice, Roy; Hucker, Ernest (1995). Bilbie and the Chew Valley clock makers. The authors. ISBN 0-9526702-0-8.

- ↑ "Church of St Mary the Virgin". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ↑ "Church Room". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Baptist Church". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ Parramore, Thomas C. (2007). First to Fly: North Carolina and the Beginnings of Aviation. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8078-5470-9.

- ↑ "High hopes for replica plane". BBC News. 10 October 2001. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ Harvey, David (1999). Monuments to Courage : Victoria Cross Headstones and Memorials. Vol.1, 1854–1916. Kevin & Kay Patience. OCLC 59437297.

- ↑ "Margaret Bondfield (1873–1953)". Timeline. TUC History. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ↑ Duncan A. Young; Andrew P. Wright; Jason L. Roberts; Roland C. Warner; Neal W. Young; Jamin S. Greenbaum; Dustin M. Schroeder; John W. Holt; David E. Sugden; Donald D. Blankenship; Tas D. van Ommen; Martin J. Siegert (2011). "A dynamic early East Antarctic Ice Sheet suggested by ice-covered fjord landscapes". Nature. 474 (7349): 72–75. doi:10.1038/nature10114. PMID 21637255.

- ↑ "Technical Paper - Aluminium Conductor Rail for London Underground, by Mr. D.J. Hartland" (PDF). Brecknell Willis, RTI. 1998.

- ↑ Brooks, Jason. "Chard men discover the secrets of The Frozen Deep". This is the Westcounty. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chard, Somerset. |