Cajal body

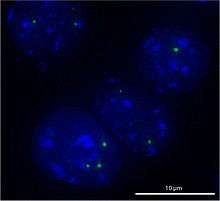

Cajal bodies (CBs) also coiled bodies, are spherical sub-organelles of 0.3-1.0 µm in diameter found in the nucleus of proliferative cells like embryonic cells and tumor cells, or metabolically active cells like neurons. In contrast to cytoplasmic organelles, CBs lack any phospholipid membrane which would separate their content, largely consisting of proteins and RNA, from the surrounding nucleoplasm. They were first reported by Santiago Ramón y Cajal in 1903, who called them nucleolar accessory bodies due to their association with the nucleoli in neuronal cells.[1] They were rediscovered with the use of the electron microscope (EM) and named coiled bodies, according to their appearance as coiled threads on EM images, and later renamed after their discoverer.[2] Research on CBs was accelerated after discovery and cloning of the marker protein p80/Coilin.[3] CBs have been implicated in RNA-related metabolic processes such as snRNPs biogenesis, maturation and recycling, histone mRNA processing and telomere maintenance. CBs assemble RNA which is used by telomerase to add nucleotides to the ends of telomeres.[4]

History

CBs were initially discovered by neurobiologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal in 1903 as small argyrophilic spots in nuclei of silver-stained neuronal cells. Because of their close association with nucleoli he named them nucleolar accessory bodies. Later on, they were forgotten and rediscovered multiple times independently which led to a state where scientists from different research fields used different names for the same structure. Names used for CBs included "sphere organelles", "Binnenkörper", "nucleolar bodies" or "coiled bodies". The name coiled bodies comes from observation of electron microscopists Monneron and Bernhard. They described bodies as aggregates composed of coiled threads with thickness of 400-600 Å. When using higher magnification, they appear as tiny, 50 Å thick fibrils irregularly twisted along the axis of the threads. The bodies were even predicted to consist of ribonucleoproteins since treatment of cells with protease and RNase together, but not alone, caused dramatic changes to the structure of CBs.[5]

Localization

Cajal bodies are only found in nuclei of plant, yeast, and animal cells.[6] The cells in which Cajal bodies are most apparent usually demonstrate high levels of transcriptional activity, and are often dividing rapidly.[7]

CBs and cell cycle

They are about 0.1-2.0 micrometres and are found one to five per nucleus. The number varies in different types of cells and over the cell cycle. Maximum number is reached in mid G1 phase and towards G2 they become larger and their number decreases. CBs disassemble during the M phase and reappear again later in G1 phase. Cajal bodies are possibly sites of assembly or modification of the transcription machinery of the nucleus.[8]

Functions

CBs are bound to the nucleolus by coilin proteins. P80-coilin is a specific marker for coiled bodies,[9] and demonstrates these bodies tend to be associated with the nucleolus when cells are not dividing. Cajal bodies are associated with telomerase assembly and recruitment via a CAB-RNA sequence common in both CB RNAs (scaRNAs) and the RNA component of telomerase (TERC). TCAB1 recognizes the CAB sequence in both and recruits telomerase to the CBs.

CBs contain high concentrations of splicing small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), possibly indicating that they function to modify RNA after it has been transcribed from DNA.[10] Experimental evidence indicates that CBs contribute to the biogenesis of telomerase enzyme, and assist in subsequent transport of telomerase to telomeres.[11][12]

References

- ↑ Cajal SR (1903). "Un sencillo metodo de coloracion selectiva del reticulo protoplasmico y sus efectos en los diversos organos nerviosos de vertebrados e invertebrados". Trab Lab Investig Biol Univ Madr. 2: 129–221.

- ↑ Gall, JG; Bellini, M; Wu, Z; Murphy, C (December 1999). "Assembly of the nuclear transcription and processing machinery: Cajal bodies (coiled bodies) and transcriptosomes.". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 10 (12): 4385–402. doi:10.1091/mbc.10.12.4385. PMC 25765

. PMID 10588665.

. PMID 10588665. - ↑ Andrade LE, Chan EK, Raska I, Peebles CL, Roos G, Tan EM (June 1991). "Human autoantibody to a novel protein of the nuclear coiled body: immunological characterization and cDNA cloning of p80-coilin". J. Exp. Med. 173 (6): 1407–19. doi:10.1084/jem.173.6.1407. PMC 2190846

. PMID 2033369.

. PMID 2033369. - ↑ Wright, W.E., Zhao, Y.; Abreu, E.; Kim, J.; Stadler, G.; Eskiocak, U.; Terns, M.P.; Terns, R.M.; Shay, J.W. (6 May 2011). "Processive and Distributive Extension of Human Telomeres by Telomerase Under Homeostatic and Non-equilibrium Conditions". Molecular Cell. 42 (3): 297–307. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.020. PMC 3108241

. PMID 21549308.

. PMID 21549308. - ↑ Monneron A, Bernhard W (May 1969). "Fine structural organization of the interphase nucleus in some mammalian cells". J. Ultrastruct. Res. 27 (3): 266–88. doi:10.1016/S0022-5320(69)80017-1. PMID 5813971.

- ↑ Cioce, Mario; Lamond, Angus I. (2005). "CAJAL BODIES: A Long History of Discovery". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 21 (1): 105–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.103738. ISSN 1081-0706.

- ↑ Ogg SC, Lamond A (2002). "Cajal bodies and coilin—moving towards function". J Cell Biol. 159 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1083/jcb.200206111. PMC 2173504

. PMID 12379800.

. PMID 12379800. - ↑ Cremer T, Cremer C (2001). "Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells". Nat Rev Genet. 2 (4): 292–301. doi:10.1038/35066075. PMID 11283701.

- ↑ Raska I, Ochs RL, Andrade LE, et al. (1990). "Association between the nucleolus and the coiled body". J. Struct. Biol. 104 (1–3): 120–7. doi:10.1016/1047-8477(90)90066-L. PMID 2088441.

- ↑ Nizami Z, Deryusheva S, Gall JG (2010). "The Cajal body and histone locus body". COLD SPRING HARBOR PERSPECTIVES IN BIOLOGY. 2 (7): a000653. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000653. PMC 2890199

. PMID 20504965.

. PMID 20504965. - ↑ Jády BE, Richard P, Bertrand E, Kiss T (2006). "Cell cycle-dependent recruitment of telomerase RNA and Cajal bodies to human telomeres". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 17 (2): 944–954. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0904. PMC 1356602

. PMID 16319170.

. PMID 16319170. - ↑ Tomlinson RL, Ziegler TD, Supakorndej T, Terns RM, Terns MP (2006). "Cell cycle-regulated trafficking of human telomerase to telomeres". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 17 (2): 955–965. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0903. PMC 1356603

. PMID 16339074.

. PMID 16339074.