Metal carbonyl

An iron atom with five CO ligands

Metal carbonyls are coordination complexes of transition metals with carbon monoxide ligands. Metal carbonyls are useful in organic synthesis and as catalysts or catalyst precursors in homogeneous catalysis, such as hydroformylation and Reppe chemistry. In the Mond process, nickel carbonyl is used to produce pure nickel. In organometallic chemistry, metal carbonyls serve as precursors for the preparation of other organometalic complexes.

Metal carbonyls are toxic by skin contact, inhalation or ingestion, in part because of their ability to carbonylate hemoglobin to give carboxyhemoglobin, which prevents the binding of O2.[1]

Nomenclature and terminology

The nomenclature of the metal carbonyls depends on the charge of the complex, the number and type of central atoms, and the number and type of ligands and their binding modes. They occur as neutral complexes, as positively charged metal carbonyl cations or as negatively charged metal carbonylates. The carbon monoxide ligand may be bound terminally to a single metal atom or bridging to two or more metal atoms. These complexes may be homoleptic, that is containing only CO ligands, such as nickel carbonyl (Ni(CO)4), but more commonly metal carbonyls are heteroleptic and contain a mixture of ligands.

Mononuclear metal carbonyls contain only one metal atom as the central atom. Except vanadium hexacarbonyl only metals with even order number such as chromium, iron, nickel and their homologs build neutral mononuclear complexes. Polynuclear metal carbonyls are formed from metals with odd order numbers and contain a metal-metal bond.[2] Complexes with different metals, but only one type of ligand will be referred to as isoleptic.[2]

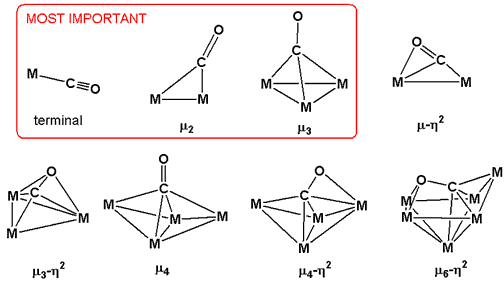

The number of carbon monoxide ligands in a metal carbonyl complex is described by a Greek numeral, followed by the word carbonyl. Carbon monoxide has different binding modes in metal carbonyls. They differ in the hapticity and the bridging mode. The hapticity describes the number of carbon monoxide ligands, which are directly bonded to the central atom. The denomination shall be made by the letter ηn, which is prefixed to the name of the complex. The superscript n indicates the number of bounded atoms. In monohapto coordination, such as in terminally bonded carbon monoxide, the hapticity is 1 and it is usually not separately designated. If carbon monoxide is bound via the carbon atom and via the oxygen to the metal, it will be referred to as dihapto coordinated η2.[3]

The carbonyl ligand engages in a range of bonding modes in metal carbonyl dimers and clusters. In the most common bridging mode, the CO ligand bridges a pair of metals. This bonding mode is observed in the commonly available metal carbonyls: Co2(CO)8, Fe2(CO)9, Fe3(CO)12, and Co4(CO)12.[1][4] In certain higher nuclearity clusters, CO bridges between three or even four metals. These ligands are denoted μ3-CO and μ4-CO. Less common are bonding modes in which both C and O bond to the metal, e.g. μ3-η2.

Structure and bonding

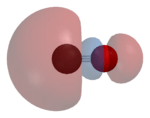

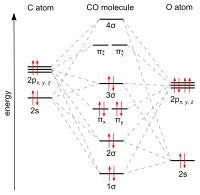

Carbon monoxide bonds to transition metals using "synergistic π* back-bonding." The bonding has three components, giving rise to a partial triple bond. A sigma bond arises from overlap of the nonbonding (or weakly anti-bonding) sp-hybridized electron pair on carbon with a blend of d-, s-, and p-orbitals on the metal. A pair of π bonds arises from overlap of filled d-orbitals on the metal with a pair of π-antibonding orbitals projecting from the carbon atom of the CO. The latter kind of binding requires that the metal have d-electrons, and that the metal is in a relatively low oxidation state (<+2) which makes the back donation process favorable. As electrons from the metal fill the π-antibonding orbital of CO, they weaken the carbon-oxygen bond compared with free carbon monoxide, while the metal-carbon bond is strengthened. Because of the multiple bond character of the M-CO linkage, the distance between the metal and carbon atom is relatively short, often < 1.8 Â, about 0.2 Â shorter than a metal-alkyl bond. Several canonical forms can be drawn to describe the approximate metal carbonyl bonding modes.

Resonance structures of a metal carbonyl, from left to right the contributions of the right-hand-side canonical forms increase as the back bonding power of M to CO increases. |

Infrared spectroscopy is a sensitive probe for the presence of bridging carbonyl ligands. For compounds with doubly bridging CO ligands, denoted μ2-CO or often just μ-CO, νCO, νCO is usually shifted by 100–200 cm−1 to lower energy compared to the signatures of terminal CO, i.e. in the region 1800 cm−1. Bands for face capping (μ3) CO ligands appear at even lower energies. Typical values for rhodium cluster carbonyls are:[5] In addition to symmetrical bridging modes, CO can be found bridge unsymmetrically or through donation from a metal d orbital to the π* orbital of CO.[6][7][8] The increased π-bonding due to back-donation from multiple metal centers results in further weakening of the C-O bond.

Physical characteristics

Most mononuclear carbonyl complexes are colorless or pale yellow volatile liquids or solids that are flammable and toxic.[9] Vanadium hexacarbonyl, a uniquely stable 17-electron metal carbonyl, is a blue-black solid.[1] Di- and polymetallic carbonyls tend to be more deeply colored. Triiron dodecacarbonyl (Fe3(CO)12) forms deep green crystals. The crystalline metal carbonyls often are sublimable in vacuum, although this process is often accompanied by degradation. Metal carbonyls are soluble in nonpolar and polar organic solvents such as benzene, diethyl ether, acetone, glacial acetic acid and carbon tetrachloride. Some salts of cationic and anionic metal carbonyls are soluble in water or lower alcohols.

Analytical characterization

Apart from X-ray crystallography, important analytical techniques for the characterization of metal carbonyls are infrared spectroscopy and 13C NMR spectroscopy. These two techniques provide structural information on two very different time scales. Infrared active vibrational modes, such as CO-stretching vibrations are often fast compared to intramolecular processes, whereas NMR transitions occur at lower frequencies and thus sample structures on a time scale that, it turns out, is comparable to the rate of intramolecular ligand exchange processes. NMR data provide information on "time-averaged structures," whereas IR is an instant "snapshot."[10] Illustrative of the differing time scales, investigation of dicobalt octacarbonyl (Co2(CO)8) by means of infrared spectroscopy provides 13 νCO bands, far more than expected for a single compound. This complexity reflects the presence of isomers with and without bridging CO-ligands. The 13C-NMR spectrum of the same substance exhibits only a single signal at a chemical shift of 204 ppm. This simplicity indicates that the isomers quickly (on the NMR timescale) interconvert.

Iron pentacarbonyl exhibits only a single 13C-NMR signal owing to rapid exchange of the axial and equatorial CO ligands by Berry pseudorotation.

Infrared spectra

The most important technique for characterizing metal carbonyls is infra-red spectroscopy.[12] The C-O vibration, typically denoted νCO, occurs at 2143 cm−1 for CO gas. The energies of the νCO band for the metal carbonyls correlates with the strength of the carbon-oxygen bond, and inversely correlated with the strength of the π-backbonding between the metal and the carbon. The π basicity of the metal center depends on a lot of factors; in the isoelectronic series (Ti to Fe) at the bottom of this section, the hexacarbonyls show decreasing π-backbonding as one increases (makes more positive) the charge on the metal. π-Basic ligands increase π-electron density at the metal, and improved backbonding reduces νCO. The Tolman electronic parameter uses the Ni(CO)3 fragment to order ligands by their π-donating abilities.[13][14]

The number of vibrational modes of a metal carbonyl complex can be determined by group theory. Only vibrational modes that transform as the electric dipole operator will have non-zero direct products and are observed. The number of observable IR transitions (but not the energies) can thus be predicted.[15][16][17] For example, the CO ligands of octahedral complexes, e.g. Cr(CO)6, transform as a1g, eg, and t1u, but only the t1u mode (anti-symmetric stretch of the apical carbonyl ligands) is IR-allowed. Thus, only a single νCO band is observed in the IR spectra of the octahedral metal hexacarbonyls. Spectra for complexes of lower symmetry are more complex. For example, the IR spectrum of Fe2(CO)9 displays CO bands at 2082, 2019, 1829 cm−1. The number of IR-observable vibrational modes for some metal carbonyls are shown in the table. Exhaustive tabulations are available.[12]

| Compound | νCO (cm−1) | 13C NMR shift | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 2143 | 181 | |

| Ti(CO)6−2 | 1748 | ||

| V(CO)6−1 | 1859 | ||

| Cr(CO)6 | 2000 | 212 | |

| Mn(CO)5+ | 2100 | ||

| Fe(CO)42+ | 2204 | ||

| Fe(CO)5 | 2022, 2000 | 209 |

| carbonyl | νCO, µ1 (cm−1) | νCO, µ2 (cm−1) | νCO, µ3 (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rh2(CO)8 | 2060, 2084 | 1846, 1862 | |

| Rh4(CO)12 | 2044, 2070, 2074 | 1886 | |

| Rh6(CO)16 | 2045, 2075 | 1819 |

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

The traditional method for the study of metal carbonyls is the 13C NMR spectroscopy. To improve the sensitivity of this technique, complexes are often enriched 13CO. Typical range for the chemical shift for terminally bound ligands is 150 to 220 ppm. Bridging ligands absorb between 230 and 280 ppm.[1] The 13C signals shift toward higher fields with an increasing atomic number of the central metal.

The nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy can be used for experimental determination of the complex dynamics.[10] The activation energy of ligand exchanges processes can be determined by the temperature dependence of the line broadening.[18]

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry provides information about the structure and composition of the complexes. Spectra for metal polycarbonyls are often easily interpretable, because the dominant fragmentation process is the loss of carbonyl ligands (m/z = 28).

- M(CO)n+ → M(CO)n-1+ + CO

Electron impact ionization is the most common technique for characterizing the neutral metal carbonyls. Neutral metal carbonyls can be converted to charged species by derivatization, which enables the use of electrospray ionization, instrumentation for which is often widely available. For example, treatment of a metal carbonyl with alkoxide generates an anionic metallaformate that is amenable to analysis by ESI-MS:

- LnM(CO) + RO− → [LnM-C(=O)OR]−

Some metal carbonyls react with azide to give isocyanato complexes with release of nitrogen.[19] By adjusting the cone voltage and/or temperature, the degree of fragmentation can be controlled. The molar mass of the parent complex can be determined, as well as information about structural rearrangements involving loss of carbonyl ligands under ESI-MS conditions.[20]

Occurrence in nature

In the investigation of the infrared spectrum of the Galactic Center monoxide vibrations of iron carbonyls in interstellar dust clouds were detected.[22] Iron carbonyl clusters were also observed in Jiange H5 chondrites identified by infrared spectroscopy. Four infrared stretching frequencies were found for the terminal and bridging carbon monoxide ligands.[23]

In the oxygen-rich atmosphere of earth metal carbonyls are subject to oxidation to the metal oxides. It is discussed whether in the reducing hydrothermal environments of the pre-biotic prehistory such complexes were formed and could have been available as catalysts for the synthesis of critical biochemical compounds such as pyruvic acid.[24] Traces of the carbonyls of iron, nickel, and tungsten were found in the gaseous emanations from the sewage sludge of municipal treatment plants.[25]

The hydrogenase enzymes contain CO bound to iron. Apparently the CO stabilizes low oxidation states, which facilitates the binding of hydrogen. The enzymes carbon monoxide dehydrogenase and acetyl coA synthase also are involved in bio-processing of CO.[26] Carbon monoxide containing complexes are invoked for the toxicity of CO and signaling.[27]

Synthesis

The synthesis of metal carbonyls is subject of intense organometallic research. Since the work of Mond and then Hieber, many procedures have been developed for the preparation of mononuclear metal carbonyls as well as homo-and hetero-metallic carbonyl clusters.[28]

Direct reaction of metal with carbon monoxide

Nickel tetracarbonyl and iron pentacarbonyl can be prepared according to the following equations by reaction of finely divided metal with carbon monoxide:[29]

- Ni + 4 CO → Ni(CO)4 (1 bar, 55 °C)

- Fe + 5 CO → Fe(CO)5 (100 bar, 175 °C)

Nickel carbonyl is formed with carbon monoxide already at 80 °C and atmospheric pressure, finely divided iron reacts at temperatures between 150 and 200 °C and a carbon monoxide pressure of 50 to 200 bar.[30] Other metal carbonyls are prepared by less direct methods.

Reduction of metal salts and oxides

Some metal carbonyls are prepared by the reduction of metal halides in the presence of high pressure of carbon monoxide. A variety of reducing agents are employed, including copper, aluminum, hydrogen, as well as metal alkyls such as triethylaluminum. Illustrative is the formation of chromium hexacarbonyl from anhydrous chromium(III) chloride in benzene with aluminum as a reducing agent, and aluminum chloride as the catalyst:[29]

- CrCl3 + Al + 6 CO → Cr(CO)6 + AlCl3

The use of metal alkyls, e.g. triethylaluminium and diethylzinc as the reducing agent leads to the oxidative coupling of the alkyl radical to the dimer:

- WCl6 + 6 CO + 2 Al(C2H5)3 → W(CO)6 + 2 AlCl3 + 3 C4H10

Tungsten, molybdenum, manganese, and rhodium salts may be reduced with lithium aluminum hydride. Vanadium hexacarbonyl is prepared with sodium as a reducing agent in chelating solvents such as diglyme.[9]

- VCl3 + 4 Na + 6 CO 2 diglyme → Na(diglyme)2[V(CO)6] + 3 NaCl

- [V(CO)6]− + H+ → H[V(CO)6] → 1/2 H2 + V(CO)6

In aqueous phase nickel or cobalt salts can be reduced, for example, by sodium dithionite. In the presence of carbon monoxide, cobalt salts are quantitatively converted to the tetracarbonylcobalt(-1) anion:[9]

- Co2+ + 1.5 S2O42− + 6 OH− + 4 CO → Co(CO)4− + 3 SO32− + 3 H2O

Some metal carbonyls are prepared using CO as the reducing agent. In this way, Hieber and Fuchs first prepared dirhenium decacarbonyl from the oxide:[31]

- Re2O7 + 17 CO → Re2(CO)10 + 7 CO2

If metal oxides are used carbon dioxide is formed as a reaction product. In the reduction of metal chlorides with carbon monoxide phosgene is formed, as in the preparation of osmium carbonyl chloride from the chloride salts.[28] Carbon monoxide is also suitable for the reduction of sulfides, where carbonyl sulfide is the byproduct.

Photolysis and thermolysis

Photolysis or thermolysis of mononuclear carbonyls generates bi- and multimetallic carbonyls such as diiron nonacarbonyl (Fe2(CO)9).[32][33] On further heating, the products decompose eventually into the metal and carbon monoxide.

- 2 Fe(CO)5 → Fe2(CO)9 + CO

The thermal decomposition of triosmium dodecacarbonyl (Os3(CO)12) provides higher-nuclear osmium carbonyl clusters such as Os4(CO)13, Os6(CO)18 up to Os8(CO)23.[9]

Mixed ligand carbonyls of ruthenium, osmium, rhodium, and iridium are often generated by abstraction of CO from solvents such as dimethylformamide (DMF) and 2-methoxyethanol. Typical is the synthesis of IrCl(CO)(PPh3)2 from the reaction of iridium(III) chloride and triphenylphosphine in boiling DMF solution.

Salt metathesis

Salt metathesis reaction of for example KCo(CO)4 with [Ru(CO)3Cl2]2 leads selectively to mixed-metal carbonyls such as RuCo2(CO)11.[34]

- 4 KCo(CO)4 + [Ru(CO)3Cl2]2 → 2 RuCo2(CO)11 + 4 KCl + 11 CO

Metal carbonyl cations and carbonylates

The synthesis of ionic carbonyl complexes is possible by oxidation or reduction of the neutral complexes. Anionic metal carbonylates can be obtained for example by reduction of dinuclear complexes with sodium. A familiar example is the sodium salt of iron tetracarbonylate (Na2Fe(CO)4,Collman's reagent), which is used in organic synthesis.[35]

The cationic hexacarbonyl salts of manganese, technetium and rhenium can be prepared from the carbonyl halides under carbon monoxide pressure by reaction with a Lewis acid.

- Mn(CO)5Cl + AlCl3 + CO → Mn(CO)6+AlCl4−

The use of strong acids succeeded in preparing gold carbonyl cations such as [Au(CO)2]+, which is used as a catalyst for the carbonylation of olefins.[36] The cationic platinum carbonyl complex [Pt(CO)4]+ can be prepared by working in so-called super acids such as antimony pentafluoride.

Reactions

Metal carbonyls are important precursors for the synthesis of other organometalic complexes. The main reactions are the substitution of carbon monoxide by other ligands, the oxidation or reduction reactions of the metal center and reactions of carbon monoxide ligand.

CO substitution

The substitution of CO ligands can be induced thermally or photochemically by donor ligands. The range of ligands is large, and includes phosphines, cyanide (CN−), nitrogen donors, and even ethers, especially chelating ones. Olefins, especially diolefins, are effective ligands that afford synthetically useful derivatives. Substitution of 18-electron complexes generally follows a dissociative mechanism, involving 16-electron intermediates.

Substitution proceeds via a dissociative mechanism:

- M(CO)n → M(CO)n-1 + CO

- M(CO) n-1 + L → M(CO)n-1L

The dissociation energy is 105 kJ mol−1 for nickel carbonyl and 155 kJ mol−1 for chromium hexacarbonyl.[1]

Substitution in 17-electron complexes, which are rare, proceeds via associative mechanisms with a 19-electron intermediates.

- M(CO)n + L → M(CO)nL

- M(CO)nL → M(CO)n-1L + CO

The rate of substitution in 18-electron complexes is sometimes catalysed by catalytic amounts of oxidants, via electron-transfer.[37]

Reduction

Metal carbonyls react with reducing agents such as metallic sodium or sodium amalgam to give carbonylmetalate (or carbonylate) anions:

- Mn2(CO)10 + 2 Na → 2 Na[Mn(CO)5]

For iron pentacarbonyl, one obtains the tetracarbonylferrate with loss of CO:

- Fe(CO)5 + 2 Na → Na2[Fe(CO)4] + CO

Mercury can insert into the metal-metal bonds of some polynuclear metal carbonyls:

- Co2(CO)8 + Hg → (CO)4Co-Hg-Co(CO)4

Nucleophilic attack at CO

The CO ligand is often susceptible to attack by nucleophiles. For example, trimethylamine oxide and bistrimethylsilylamide convert CO ligands to CO2 and CN−, respectively. In the "Hieber base reaction", hydroxide ion attacks the CO ligand to give a metallacarboxylic acid, followed by the release of carbon dioxide and the formation of metal hydrides or carbonylmetalates. A well-known example of this nucleophilic addition reaction is the conversion of iron pentacarbonyl to hydridorion tetracarbonyl anion:

- Fe(CO)5 + NaOH → Na[Fe(CO)4CO2H]

- Na[Fe(CO)4COOH] + NaOH → Na[HFe(CO)4] + NaHCO3

Protonation of the hydrido anion gives the neutral iron tetracarbonyl hydride:

- Na[HFe(CO)4] + H+ → H2Fe(CO)4 + Na+

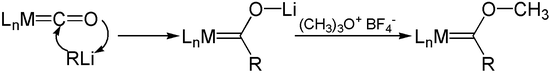

Organolithium reagents add with metal carbonyls to acylmetal carbonyl anions. O-alkylation of these anions, e.g. with Meerwein salts, affords Fischer carbenes.

With electrophiles

Despite being in low formal oxidation states, metal carbonyls are relatively unreactive toward many electrophiles. For example, they resist attack by alkylating agents, mild acids, mild oxidizing agents. Most metal carbonyls do undergo halogenation. Iron pentacarbonyl, for example, forms ferrous carbonyl halides:

- Fe(CO)5 + X2 → Fe(CO)4X2 + CO

Metal-metal bonds are cleaved by halogens. Depending on the electron-counting scheme used, this can be regarded as oxidation of the metal atom:

- Mn2(CO)10 + Cl2 → 2 Mn(CO)5Cl

Compounds

Most metal carbonyl complexes contain a mixture of ligands. Examples include the historically important IrCl(CO)(P(C6H5)3)2 and the anti-knock agent (CH3C5H4)Mn(CO)3. The parent compounds for many of these mixed ligand complexes are the binary carbonyls, i.e. species of the formula [Mx(CO)n]z, many of which are commercially available. The formula of many metal carbonyls can be inferred from the 18 electron rule.

Charge-neutral binary metal carbonyls

- Group 4 elements with 4 valence electrons are rare, but substituted derivatives of Ti(CO)7 are known.

- Group 5 elements with 5 valence electrons, again are subject to steric effects that prevent the formation of M-M bonded species such as V2(CO)12, which is unknown. The 17 VE V(CO)6 is however well known.

- Group 6 elements with 6 valence electrons form metal carbonyls Cr(CO)6, Mo(CO)6, and W(CO)6 (6 + 6x2 = 18 electrons). Group 6 elements (as well as group 7) are well also well known for exhibiting the cis effect (the labilization of CO in the cis position) in organometallic synthesis.

- Group 7 elements with 7 valence electrons form metal carbonyl dimers Mn2(CO)10, Tc2(CO)10, and Re2(CO)10 (7 + 1 + 5x2 = 18 electrons).

- Group 8 elements with 8 valence electrons form metal carbonyls Fe(CO)5, Ru(CO)5 and Os(CO)5 (8 + 5x2 = 18 electrons). The heavier two members are unstable, tending to decarbonylate to give Ru3(CO)12, and Os3(CO)12. The two other principal iron carbonyls are Fe3(CO)12 and Fe2(CO)9.

- Group 9 elements with 9 valence electrons and are expected to form metal carbonyl dimers M2(CO)8. In fact the cobalt derivative of this octacarbonyl is the only stable member, but all three tetramers are well known: Co4(CO)12, Rh4(CO)12, Rh6(CO)16, and Ir4(CO)12 (9 + 3 + 3x2 = 18 electrons). Co2(CO)8 unlike the majority of the other 18 VE transition metal carbonyls is sensitive to oxygen.

- Group 10 elements with 10 valence electrons form metal carbonyls Ni(CO)4 (10 + 4x2 = 18 electrons). Curiously Pd(CO)4 and Pt(CO)4 are not stable.

Anionic binary metal carbonyls

- Group 4 elements as dianions resemble neutral group 6 derivatives: [Ti(CO)6]2−.[38]

- Group 5 elements as monoanions resemble again neutral group 6 derivatives: [V(CO)6]−.

- Group 7 elements as monoanions resemble neutral group 8 derivatives: [M(CO)5]− (M = Mn, Tc, Re).

- Group 8 elements as dianaions resemble neutral group 10 derivatives: [M(CO)4]2− (M = Fe, Ru, Os). Condensed derivatives are also known.

- Group 9 elements as monoanions resemble neutral group 10 metal carbonyl. [Co(CO)4]− is the best studied member.

Large anionic clusters of Ni, Pd, and Pt are also well known.

Cationic binary metal carbonyls

- Group 7 elements as monocations resemble neutral group 6 derivative [M(CO)6]+ (M = Mn, Tc, Re).

- Group 8 elements as dications also resemble neutral group 6 derivatives [M(CO)6]2+ (M = Fe, Ru, Os).[39]

Metal carbonyl hydrides

| Metal Carbonyl hydride | pKa |

|---|---|

| HCo(CO)4 | "strong" |

| HCo(CO)3(P(OPh)3) | 5.0 |

| HCo(CO)3(PPh3) | 7.0 |

| HMn(CO)5 | 7.1 |

| H2Fe(CO)4 | 4.4, 14 |

| [HCo(dmgH)2PBu3] | 10.5 |

Metal carbonyls are relatively distinctive in forming complexes with negative oxidation states. Examples include the anions discussed above. These anions can be protonated to give the corresponding metal carbonyl hydrides. The neutral metal carbonyl hydrides are often volatile and can be quite acidic.[40]

Applications

Metallurgical uses

Metal carbonyls are used in several industrial processes. Perhaps the earliest application was the extraction and purification of nickel via nickel tetracarbonyl by the Mond process (see also carbonyl metallurgy).

By a similar process carbonyl iron, a highly pure metal powder, is prepared by thermal decomposition of iron pentacarbonyl. Carbonyl iron is used inter alia for the preparation of inductors, pigments, as dietary supplements,[41] in the production of radar-absorbing materials in the stealth technology,[42] and in Thermal spraying.

Catalysis

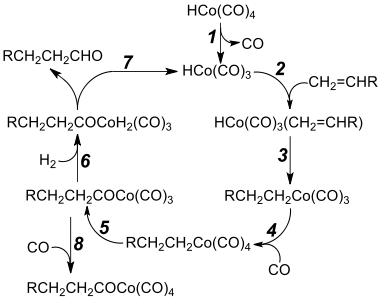

Metal carbonyls are used in a number of industrially important carbonylation reactions. In the oxo process, an olefin, dihydrogen, and carbon monoxide react together with a catalyst (e.g. dicobalt octacarbonyl) to give aldehydes. Illustrative is the production of butyraldehyde:

- H2 + CO + CH3CH=CH2 → CH3CH2CH2CHO

Butyraldehyde is converted on an industrial scale to 2-Ethylhexanol, a precursor to PVC plasticizers, by aldol condensation, followed by hydrogenation of the resulting hydroxyaldehyde. The "oxo aldehydes" resulting from hydroformylation are used for large-scale synthesis of fatty alcohols, which are precursors to detergents. The hydroformylation is a reaction with high atom economy, especially if the reaction proceeds with high regioselectivity.

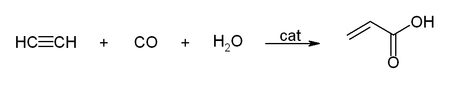

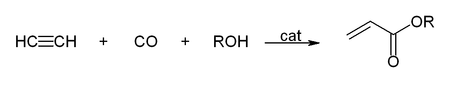

Another important reaction catalyzed by metal carbonyls is the hydrocarboxylation. The example below is for the synthesis of acrylic acid and acrylic acid esters:

Also the cyclization of acetylene to cyclooctatetraene uses metal carbonyl catalysts:[43]

In the Monsanto and Cativa processes, acetic acid is produced from methanol, carbon monoxide, and water using hydrogen iodide as well as rhodium and iridium carbonyl catalysts, respectively. Related carbonylation reactions afford acetic anhydride.

CO-releasing molecules (CO-RMs)

Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules are metal carbonyl complexes that are being developed as potential drugs to release CO. At low concentrations, CO functions as a vasodilatory and an anti-inflammatory agent. CO-RMs have been conceived as a pharmacological strategic approach to carry and deliver controlled amounts of CO to tissues and organs.[44]

Related compounds

Many ligands are known to form homoleptic and mixed ligand complexes that are analogous to the metal carbonyls.

Nitrosyl complexes

Metal nitrosyls, compounds featuring NO ligands, are numerous. In contrast to metal carbonyls, however, homoleptic metal nitrosyls are rare. NO is a stronger pi-acceptor than CO. Well known nitrosyl carbonyls include CoNO(CO)3 and Fe(NO)2(CO)2, which are analogues of Ni(CO)4.[45]

Thiocarbonyls complexes

Complexes containing CS are known but are uncommon.[46][47] The rarity of such complexes is attributable in part to the fact that the obvious source material, carbon monosulfide, is unstable. Thus, the synthesis of thiocarbonyl complexes requires more elaborate routes, such as the reaction of disodium tetracarbonylferrate with thiophosgene:

- Na2Fe(CO)4 + CSCl2 → Fe(CO)4CS + 2 NaCl

Complexes of CSe and CTe are very rare.

Phosphine complexes

All metal carbonyls undergo substitution by organophosphorus ligands. For example, the series Fe(CO)5-x(PR3)x is well known for various phosphine ligands for x = 1, 2, and 3. PF3 behaves similarly but is remarkable because it readily forms homoleptic analogues of the binary metal carbonyls. For example, the volatile, stable complexes Fe(PF3)5 and Co2(PF3)8 represent CO-free analogues of Fe(CO)5 and Co2(CO)8 (unbridged isomer).

Isocyanide complexes

Isocyanides also form extensive families of complexes that are related to the metal carbonyls. Typical isocyanide ligands are methyl and t-butyl isocyanides (Me3CNC). A special case is CF3NC, an unstable molecule that forms stable complexes whose behavior closely parallels that of the metal carbonyls.

Toxicology

The toxicity of metal carbonyls is due to toxicity of carbon monoxide, the metal, and because of the volatility and instability of the complexes. Exposure occurs by inhalation, or for liquid metal carbonyls by ingestion or due to the good fat solubility by skin resorption. Most clinical experience were gained from toxicological poisoning with nickel carbonyl and iron pentacarbonyl. Nickel carbonyl is considered as one of the strongest inhalation poisons.[48]

Inhalation of nickel carbonyl causes acute non-specific symptoms similar to a carbon monoxide poisoning as nausea, cough, headaches, fever and dizziness. After some time, severe pulmonary symptoms such as cough, tachycardia cyanosis or problems in the gastrointestinal tract occur. In addition to pathological alterations of the lung, such as by metallation of the alveoli, damages are observed in the brain, liver, kidneys, adrenal glands and the spleen. A metal carbonyl poisoning often requires a long-lasting recovery.[49]

Chronic exposure by inhalation of low concentrations of nickel carbonyl can cause neurological symptoms such as insomnia, headaches, dizziness and memory loss.[49] Nickel carbonyl is considered carcinogenic, but it can take 20 to 30 years from the start of exposure to the clinical manifestation of cancer.[50]

History

Initial experiments on the reaction of carbon monoxide with metals were carried out by Justus von Liebig in 1834. By passing carbon monoxide over molten potassium he prepared a substance having the empirical formula KCO, which he called Kohlenoxidkalium.[51] As demonstrated later, the compound was not a metal carbonyl, but the potassium salt of ´hexahydroxy benzene and the potassium salt of dihydroxy acetylene[28]

The synthesis of the first true heteroleptic metal carbonyl complex was performed by Paul Schützenberger in 1868 by passing chlorine and carbon monoxide over platinum black, where dicarbonyldichloroplatinum (Pt(CO)2Cl2) was formed.[52]

Ludwig Mond, one of the founders of Imperial Chemical Industries, investigated in the 1890s with Carl Langer and Friedrich Quincke various processes for the recovery of chlorine which was lost in the Solvay process by nickel metals, oxides and salts.[28] As part of their experiments the group treated nickel with carbon monoxide. They found that the resulting gas colored the gas flame of a burner in a greenish-yellowish color; when heated in a glass tube it formed a nickel mirror. The gas could be condensed to a colorless, water-clear liquid with a boiling point of 43 °C. Thus, Mond and his coworker had discovered the first pure, homoleptic metal carbonyl, nickel tetracarbonyl (Ni(CO)4).[53] The unusual high volatility of the metal compound nickel tetracarbonyl led Kelvin with the statement that Mond had "given wings to the heavy metals".[54]

The following year, Mond and Marcellin Berthelot independently discovered iron pentacarbonyl, which is produced by a similar procedure as nickel tetracarbonyl. Mond recognized the economic potential of this class of compounds, which he commercially used in the Mond process and financed more research on related compounds. Heinrich Hirtz and his colleague M. Dalton Cowap synthesized metal carbonyls of cobalt, molybdenum, ruthenium, and diiron nonacarbonyl.[55][56] In 1906 James Dewar and H. O. Jones were able to determine the structure of Diiron nonacarbonyl, which is produced from iron pentacarbonyl by the action of sunlight.[57] After Mond, who died in 1909, the chemistry of metal carbonyls fell for several years in oblivion. The BASF started in 1924 the industrial production of iron pentacarbonyl by a process which was developed by Alwin Mittasch. The iron pentacarbonyl was used for the production of high-purity iron, so-called carbonyl iron, and iron oxide pigment.[30] Not until 1927 did A. Job and A. Cassal succeed in the preparation of chromium hexacarbonyl and tungsten hexacarbonyl, the first synthesis of other homoleptic metal carbonyls.

Walter Hieber played in the years following 1928 a decisive role in the development of metal carbonyl chemistry. He systematically investigated and discovered, among other things, the Hieber base reaction, the first known route to Metal carbonyl hydrides and synthetic pathways leading to metal carbonyls such as dirhenium decacarbonyl.[58] Hieber, who was since 1934 the Director of the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at the Technical University Munich published in four decades 249 papers on metal carbonyl chemistry.[28]

(now Max Planck Institute for Coal Research)

Also in the 1930s Walter Reppe, an industrial chemist and later board member of the BASF, discovered a number of homogeneous catalytic processes, such as the hydrocarboxylation, in which olefins or alkynes react with carbon monoxide and water to form products such as unsaturated acids and their derivatives.[28] In these reactions, for example, nickel carbonyl or cobalt carbonyls act as catalysts.[59] Reppe also discovered the cyclotrimerization and tetramerization of acetylene and its derivatives to benzene and benzene derivatives with metal carbonyls as catalysts. BASF built in the 1960s a production facility for acrylic acid by the Reppe process, which was only superseded in 1996 by more modern methods based on the catalytic propylene oxidation.

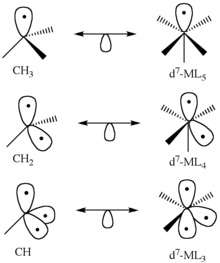

For the rational design of new complexes the concept of the isolobal analogy has been found useful. Roald Hoffmann was awarded with the Nobel Prize in chemistry for the development of the concept. The concept describes metal carbonyl fragments of M(CO)n as parts of octahedral building blocks in analogy to the tetrahedral CH3-, CH2- or CH- fragments in organic chemistry. In example Dimanganese decacarbonyl is formed in terms of the isolobal analogy of two d7Mn(CO)5 fragments, that are isolobal to the methyl radical CH3•. In analogy to how methyl radicals combine to form Ethane, these can combine to Dimanganese decacarbonyl. The presence of isolobal analog fragments does not mean that the desired structures can be synthezied. In his Nobel Prize lecture Hoffmann emphasized that the isolobal analogy is a useful but simple model, and in some cases does not lead to success.[60]

The economic benefits of metal-catalysed carbonylations, e.g. Reppe chemistry and hydroformylation, led to growth of the area. Metal carbonyl compounds were discovered in the active sites of three naturally occurring enzymes.[61]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elschenbroich, C. (2006). Organometallics. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-29390-6.

- 1 2 Arnold F. Holleman, Nils Wiberg: Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie. 102., stark umgearb. u. verb. Auflage. de Gruyter, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1, p. 1780.

- ↑ F. Albert Cotton: Proposed nomenclature for olefin-metal and other organometallic complexes. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society. 90, 1968, S. 6230–6232, doi:10.1021/ja01024a059.

- ↑ Dyson, P. J.; McIndoe, J. S. (2000). Transition Metal Carbonyl Cluster Chemistry. Amsterdam: Gordon & Breach. ISBN 90-5699-289-9.

- ↑ Allian, A. D.; Wang, Y.; Saeys, M.; Kuramshina, G. M.; Garland, M. (2006). "The Combination of Deconvolution and Density Functional Theory for the Mid-Infrared Vibrational Spectra of Stable and Unstable Rhodium Carbonyl Clusters". Vibrational Spectroscopy. 41 (1): 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.vibspec.2006.01.013.

- ↑ Spessard, G. O.; Miessler, G. L. (2010). Organometallic Chemistry (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-0-19-533099-1.

- ↑ Sargent, A. L.; Hall, M. B. (1989). "Linear Semibridging Carbonyls. 2. Heterobimetallic Complexes Containing a Coordinatively Unsaturated Late Transition Metal Center". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 111 (5): 1563–1569. doi:10.1021/ja00187a005.

- ↑ Li, P.; Curtis, M. D. (1989). "A New Coordination Mode for Carbon Monoxide. Synthesis and Structure of Cp4Mo2Ni2S2(η1, μ4-CO)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 111 (21): 8279–8280. doi:10.1021/ja00203a040.

- 1 2 3 4 Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. (2007). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (102nd ed.). Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 1780–1822. ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1.

- 1 2 Londergan, C. H.; Kubiak, C. P. (2003). "Electron Transfer and Dynamic Infrared-Band Coalescence: It Looks like Dynamic NMR spectroscopy, but a Billion Times Faster". Chemistry: A European Journal. 9 (24): 5962–5969. doi:10.1002/chem.200305028.

- ↑ Miessler, G. L.; Tarr, D. A. (2011). Inorganic Chemistry. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 109–119; 534–538.

- 1 2 Braterman, P. S. (1975). Metal Carbonyl Spectra. Academic Press.

- ↑ Crabtree, R. H. (2005). "4. Carbonyls, Phosphine Complexes, and Ligand Substitution Reactions". The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (4th ed.). pp. 87–124. doi:10.1002/0471718769.ch4.

- ↑ Tolman, C. A. (1977). "Steric effects of Phosphorus Ligands in Organometallic Chemistry and Homogeneous Catalysis". Chemical Reviews. 77 (3): 313–348. doi:10.1021/cr60307a002.

- ↑ Cotton, F. A. (1990). Chemical Applications of Group Theory (3rd ed.). Wiley Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-51094-9.

- ↑ Carter, R. L. (1997). Molecular Symmetry and Group Theory. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-14955-2.

- ↑ Harris, D. C.; Bertolucci, M. D. (1980). Symmetry and Spectroscopy: Introduction to Vibrational and Electronic Spectroscopy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855152-2.

- ↑ Riedel, E.; Alsfasser, R.; Janiak, C.; Klapötke, T. M. (2007). Moderne Anorganische Chemie. de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-019060-5.

- ↑ Henderson, W.; McIndoe, J. S. Mass Spectrometry of Inorganic, Coordination and Organometallic Compounds: Tools – Techniques – Tips. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-85015-9.

- ↑ Butcher, C. P. G.; Dyson, P. J.; Johnson, B. F. G.; Khimyak, T.; McIndoe, J. S. (2003). "Fragmentation of Transition Metal Carbonyl Cluster Anions: Structural Insights from Mass Spectrometry". Chemistry: A European Journal. 9 (4): 944–950. doi:10.1002/chem.200390116. PMID 12584710.

- ↑ Vásquez, G. B.; Ji, X.; Fronticelli, C.; Gilliland, G. L. (1998). "Human Carboxyhemoglobin at 2.2 Å Resolution: Structure and Solvent Comparisons of R-State, R2-State and T-State Hemoglobins". Acta Crystallographica D. 54 (3): 355–366. doi:10.1107/S0907444997012250.

- ↑ Tielens, A. G.; Wooden, D. H.; Allamandola, L. J.; Bregman, J.; Witteborn, F. C. (1996). "The Infrared Spectrum of the Galactic Center and the Composition of Interstellar Dust" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 461 (1): 210–222. Bibcode:1996ApJ...461..210T. doi:10.1086/177049. PMID 11539170.

- ↑ Xu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Sun, S.; Ouyang, Z. (1996). "IR Spectroscopic Evidence of Metal Carbonyl Clusters in the Jiange H5 Chondrite" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. 26: 1457–1458. Bibcode:1996LPI....27.1457X.

- ↑ Cody, G. D.; Boctor, N. Z.; Filley, T. R.; Hazen, R. M.; Scott, J. H.; Sharma, A.; Yoder, H. S. Jr. (2000). "Primordial Carbonylated Iron-Sulfur Compounds and the Synthesis of Pyruvate". Science. 289 (5483): 1337–1340. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1337C. doi:10.1126/science.289.5483.1337. PMID 10958777.

- ↑ Feldmann, J. (1999). "Determination of Ni(CO)4, Fe(CO)5, Mo(CO)6, and W(CO)6 in Sewage Gas by using Cryotrapping Gas Chromatography Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry". Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 1 (1): 33–37. doi:10.1039/A807277I. PMID 11529076.

- ↑ Jaouen, G., ed. (2006). Bioorganometallics: Biomolecules, Labeling, Medicine. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-30990-X.

- ↑ Boczkowski, J.; Poderoso, J. J.; Motterlini, R. (2006). "CO–Metal Interaction: Vital Signaling from a Lethal Gas". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 31 (11): 614–621. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.09.001. PMID 16996273.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Herrmann, W. A. (1988). "100 Jahre Metallcarbonyle. Eine Zufallsentdeckung macht Geschichte". Chemie in unserer Zeit. 22 (4): 113–122. doi:10.1002/ciuz.19880220402.

- 1 2 Huheey, J.; Keiter, E.; Keiter, R. (1995). "Metallcarbonyle". Anorganische Chemie (2nd ed.). Berlin / New York: de Gruyter.

- 1 2 Mittasch, A. (1928). "Über Eisencarbonyl und Carbonyleisen". Angewandte Chemie. 41 (30): 827–833. doi:10.1002/ange.19280413002.

- ↑ Hieber, W.; Fuchs, H. (1941). "Über Metallcarbonyle. XXXVIII. Über Rheniumpentacarbonyl". Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 248 (3): 256–268. doi:10.1002/zaac.19412480304.

- ↑ King, R. B. (1965). Organometallic Syntheses. 1: Transition-Metal Compounds. New York: Academic Press.

- ↑ Braye, E. H.; Hübel, W.; Rausch, M. D.; Wallace, T. M. (1966). H. F. Holtzlaw, ed. "Diiron Enneacarbonyl". Inorganic Syntheses. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 8: 178–181. doi:10.1002/9780470132395.ch46. ISBN 978-0-470-13239-5.

- ↑ Roland, E.; Vahrenkamp, H. (1985). "Zwei neue Metallcarbonyle: Darstellung und Struktur von RuCo2(CO)11 und Ru2Co2(CO)13". Chemische Berichte. 118 (3): 1133–1142. doi:10.1002/cber.19851180330.

- ↑ Pike, R. D. (2001). "Disodium Tetracarbonylferrate(-II)". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rd465.

- ↑ Xu, Q.; Imamura, Y.; Fujiwara, M.; Souma, Y. (1997). "A New Gold Catalyst: Formation of Gold(I) Carbonyl, [Au(CO)n]+ (n = 1, 2), in Sulfuric Acid and Its Application to Carbonylation of Olefins". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 62 (6): 1594–1598. doi:10.1021/jo9620122.

- ↑ Ohst, H. H.; Kochi, J. K. (1986). "Electron-Transfer Catalysis of Ligand Substitution in Triiron Clusters". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 108 (11): 2897–2908. doi:10.1021/ja00271a019.

- ↑ Ellis, J. E. (2003). "Metal Carbonyl Anions: from [Fe(CO)4]2− to [Hf(CO)6]2− and Beyond". Organometallics. 22 (17): 3322–3338. doi:10.1021/om030105l.

- ↑ Finze, M.; Bernhardt, E.; Willner, H.; Lehmann, C. W.; Aubke, F. (2005). "Homoleptic, σ-Bonded Octahedral Superelectrophilic Metal Carbonyl Cations of Iron(II), Ruthenium(II), and Osmium(II). Part 2: Syntheses and Characterizations of [M(CO)6][BF4]2 (M = Fe, Ru, Os)". Inorganic Chemistry. 44 (12): 4206–4214. doi:10.1021/ic0482483. PMID 15934749.

- ↑ Pearson, R. G. (1995). "The Transition-Metal-Hydrogen Bond". Chemical Reviews. 85 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1021/cr00065a002.

- ↑ Fairweather-Tait, S. J.; Teucher, B. (2002). "Iron and Calcium Bioavailability of Fortified Foods and Dietary Supplements". Nutrition Reviews. 60 (11): 360–367. doi:10.1301/00296640260385801.

- ↑ Richardson, D. (2002). Stealth-Kampfflugzeuge: Täuschen und Tarnen in der Luft. Zürich: Dietikon. ISBN 3-7276-7096-7.

- ↑ Wilke, G. (1978). "Organo Transition Metal Compounds as Intermediates in Homogeneous Catalytic Reactions" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 50 (8): 677–690. doi:10.1351/pac197850080677.

- ↑ Roberto Motterlini and Leo Otterbein "The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide" Nature Review Drug Discovery 2010, vol. 9, pp. 728-43. {{doi: 10.1038/nrd3228}}.

- ↑ Hayton, T. W.; Legzdins, P.; Sharp, W. B. (2002). "Coordination and Organometallic Chemistry of Metal−NO Complexes". Chemical Reviews. 102 (4): 935–992. doi:10.1021/cr000074t. PMID 11942784.

- ↑ Petz, W. (2008). "40 Years of Transition-Metal Thiocarbonyl Chemistry and the Related CSe and CTe Compounds". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 252 (15–17): 1689–1733. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.011.

- ↑ Hill, A. F.; Wilton-Ely, J. D. E. T. (2002). "Chlorothiocarbonyl-bis(triphenylphosphine) iridium(I) [IrCl(CS)(PPh3)2]". Inorganic Syntheses. 33: 244–245. doi:10.1002/0471224502.ch4. ISBN 0-471-20825-6.

- ↑ Madea, B. (2003). Rechtsmedizin. Befunderhebung - Rekonstruktion – Begutachtung. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-43885-8.

- 1 2 Stellman, J. M. (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. International Labour Org. ISBN 91-630-5495-7.

- ↑ Mehrtens, G.; Reichenbach, M.; Höffler, D.; Mollowitz, G. G. (1998). Der Unfallmann: Begutachtung der Folgen von Arbeitsunfällen, privaten Unfällen und Berufskrankheiten. Berlin / Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 3-540-63538-6.

- ↑ Trout, W. E. Jr. (1937). "The Metal Carbonyls. I. History; II. Preparation". Journal of Chemical Education. 14 (10): 453. Bibcode:1937JChEd..14..453T. doi:10.1021/ed014p453.

- ↑ Schützenberger, P. (1868). "Mémoires sur quelques réactions domnant lieu à la production de l'oxychlorure de carbone, et sur nouveau composé volatil de platine". Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris. 10: 188–192.

- ↑ Mond, L.; Langer, C.; Quincke, F. (1890). "Action of Carbon Monoxide on Nickel". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 57: 749–753. doi:10.1039/CT8905700749.

- ↑ Gratzer, W. (2002). "132: Metal Takes Wing". Eureka and Euphorias: The Oxford Book of Scientific Anecdotes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280403-0.

- ↑ Mond, L.; Hirtz, H.; Cowap, M. D. (1908). "Note on a Volatile Compound of Cobalt with Carbon Monoxide". Chemical News. 98: 165–166.

- ↑ Chemical Abstracts. 2: 3315. 1908. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Dewar, J.; Jones, H. O. (1905). "The Physical and Chemical Properties of Iron Carbonyl" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 76 (513): 558–577. Bibcode:1905RSPSA..76..558D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1905.0063.

- ↑ Basolo, F. (2002). From Coello to Inorganic Chemistry: A Lifetime of Reactions. Springer. p. 101. ISBN 978-030-646774-5.

- ↑ Sheldon, R. A., ed. (1983). Chemicals from Synthesis Gas: Catalytic Reactions of CO and H2. 2. Kluwer. p. 106. ISBN 978-9027714893.

- ↑ Hoffmann, R. (1981-12-08). "Building Bridges between Inorganic and Organic Chemistry". Nobelprize.org.

- ↑ Tard, C; Pickett, C. J. (2009). "Structural and Functional Analogues of the Active Sites of the [Fe]-, [NiFe]-, and [FeFe]-Hydrogenases". Chemical Reviews. 109 (6): 2245–2274. doi:10.1021/cr800542q. PMID 19438209.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metal carbonyls. |