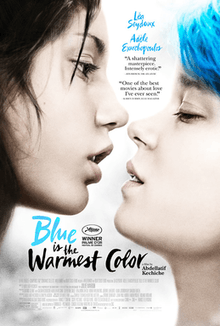

Blue Is the Warmest Colour

| Blue Is the Warmest Colour | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

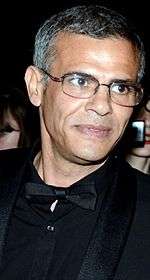

| Directed by | Abdellatif Kechiche |

| Produced by |

Abdellatif Kechiche Brahim Chioua Vincent Maraval |

| Screenplay by |

Abdellatif Kechiche Ghalia Lacroix |

| Based on |

Blue Is the Warmest Color by Julie Maroh |

| Starring |

Léa Seydoux Adèle Exarchopoulos |

| Cinematography | Sofian El Fani |

| Edited by |

Albertine Lastera Camille Toubkis Sophie Brunet Ghalia Lacroix Jean-Marie Lengelle |

Production company |

Wild Bunch Quat'sous Films France 2 Cinéma Scope Pictures Vértigo Films Radio Télévision Belge Francofone Canal+ Ciné+ France Televisions Eurimages Pictanovo Conseil Région Nord-Pas-de-Calais CNC |

| Distributed by |

Wild Bunch (France) Cinéart (Belgium) Vértigo Films (Spain) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 179 minutes[1] |

| Country |

France Belgium Spain[2][3] |

| Language | French |

| Budget | €4 million[4] |

| Box office | $19.5 million[5] |

Blue Is the Warmest Colour (French: La Vie d'Adèle – Chapitres 1 & 2 – "The Life of Adèle – Chapters 1 & 2") is a 2013 French coming-of-age romantic drama film written, produced, and directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, starring Adèle Exarchopoulos and Léa Seydoux. The film revolves around Adèle (Exarchopoulos), a French teenager who discovers desire and freedom when a blue-haired aspiring painter (Seydoux) enters her life. The film charts their relationship from Adele's high school years to her early adult life and career as a school teacher. The premise of Blue Is the Warmest Colour is based on the 2010 French graphic novel of the same name[6] by Julie Maroh,[7] which was published in North America in 2013.

Production began in March 2012 and lasted six months. Approximately 800 hours of footage was shot, including extensive B-roll footage, with Kechiche ultimately trimming the final cut of the film down to 179 minutes.[8] The film generated controversy upon its premiere at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival and before its release.[9] Much of the controversy was centred around claims of poor working conditions on set by the crew and the lead actresses, and also the film's raw depiction of sexuality.[10][11][12]

At Cannes, the film unanimously won the Palme d'Or from the official jury and the FIPRESCI Prize. It is the first film to have the Palme d'Or awarded to both the director and the lead actresses, with Seydoux and Exarchopoulos joining Jane Campion (The Piano) as the only women to have won the award.[13][14] The film had its North American premiere at the 2013 Telluride Film Festival. The film received critical acclaim and was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language.[15] Many critics declared it to be one of the best films of 2013.[16][17][18]

Plot

Adèle is an introverted high-school student whose classmates gossip constantly about boys. While crossing the street one day, she passes by a woman with short blue hair and is instantly attracted. She dates a boy at her school for a short while and they have sex, but she is ultimately dissatisfied and breaks off their relationship. After having vivid fantasies about the woman she saw on the street and having one of her female friends behave flirtatiously towards her, she becomes troubled about her sexual identity. One friend, the openly gay Valentin, seems to understand her confusion and takes her to a gay dance bar. After some time, Adèle leaves and walks into a lesbian bar, where she experiences assertive advances from some of the women. The blue haired woman is also there and intervenes, claiming Adèle is her cousin to those pursuing Adèle. The woman is Emma, a graduating art student. They become friends and begin to spend more time with each other. Adèle's friends suspect her of being a lesbian and ostracise her at school. Despite the backlash, she becomes very close to Emma. Their bond increases and before long, the two share a kiss at a picnic. They later have sex and begin a passionate relationship. Emma's artsy family is very welcoming to the couple, but Adèle tells her conservative, working-class parents that Emma is just a tutor for philosophy class.

In the years that follow, the two women live with each other as lovers. Adèle finishes school and joins the teaching staff at a local elementary school, while Emma tries to move forward with her painting career. Adèle feels ill at ease among Emma's intellectual friends and Emma belittles her teaching career, encouraging her to find fulfilment in writing. Adèle enjoys playing the stereotypical feminine role in their relationship but Emma becomes physically and emotionally distant. They gradually begin to realise how little they have in common. Emotional complexities manifest in the relationship and Adèle, in an impulsive moment of loneliness and confusion, sleeps with a male colleague.

Emma becomes aware of the brief fling and kicks Adèle out of their apartment, leaving Adèle heartbroken and alone. Time passes and although Adèle finds satisfaction in her job as a kindergarten teacher, an indescribable sadness begins to overwhelm her. The two eventually meet again in a restaurant. Adèle is still very deeply in love with Emma and despite the powerful connection that is clearly still there between them, Emma is now in a committed partnership with Lise, the pregnant woman at the party they threw a few years earlier, who now has a young daughter. It is implied that the two had known each other for years, and had become reacquainted during the party. Adèle is devastated, but holds it in. Emma admits that she does not feel sexually fulfilled but has accepted it as a part of her new phase in life. She reassures Adèle, though, that their relationship was special: "I have infinite tenderness for you. I always will. All my lifelong." The two part on amicable terms.

The film concludes with Adèle at Emma's new art exhibition. Hanging on one wall is a nude painting that Emma once did of her during the sensual bloom of their life together. Though Emma acknowledges her, her attention is primarily on the gallery's other guests and Lise. Adèle congratulates Emma on the success of her art and leaves after a brief conversation with a young man she met earlier in the film. He chases after her but heads in the wrong direction. Adèle walks away into an ambiguous future as a hang is played over the soundtrack and the film ends.

Cast

- Léa Seydoux as Emma

- Adèle Exarchopoulos as Adèle

- Salim Kechiouche as Samir

- Aurélien Recoing as Adèle's father

- Catherine Salée as Adèle's mother

- Benjamin Siksou as Antoine

- Mona Walravens as Lise

- Alma Jodorowsky as Béatrice

- Jérémie Laheurte as Thomas

- Anne Loiret as Emma's mother

- Benoît Pilot as Emma's stepfather

- Sandor Funtek as Valentin

- Fanny Maurin as Amélie

- Maelys Cabezon as Laetitia

- Stéphane Mercoyrol as Joachim

- Aurelie Lemanceau as Sabine

Production

Adaptation

Director and screenwriter Abdellatif Kechiche developed the premise for Blue Is the Warmest Colour while directing his second feature film, Games of Love and Chance (2003). He met teachers "who felt very strongly about reading, painting, writing" and it inspired him to develop a script which charts the personal life and career of a female French teacher. However, the concept was only finalised a few years later when Kechiche chanced upon Julie Maroh's graphic novel, and he saw how he could link his screenplay about a school teacher with Maroh's love story between two young women.[19] Although Maroh's story takes precedence in the adaptation, Adèle's character, named "Clémentine" in the book, differs from the original as explored by Charles Taylor in The Yale Review "The novel includes scenes of the girls being discovered in bed and thrown out of the house and speeches like ‘‘What’s horrible is that people kill each other for oil and commit genocide, not that they give their love to someone.’’[20] In the film, Adèle's parents are seemingly oblivious to her love affair with Emma and politely greet her under the impression that she is Adèle's philosophy tutor. Further themes are explored in Maroh's novel, such as addiction to prescription pills which takes the life of Clémentine / Adèle when she suffers a seizure. Regarding his intention portraying young people, Kechiche claimed: "I almost wish I was born now, because young people seem to be much more beautiful and brighter than my generation. I want to pay them tribute."[21]

Casting

In late 2011, a casting call was held in Paris to find the ideal actress for the role of Adèle. Casting director Sophie Blanvillain first spotted Adèle Exarchopoulos and then arranged for her to meet Abdellatif Kechiche. Exarchopoulos described how her auditions with Kechiche over the course of two months consisted of improvisation of scenarios, discussions and also of them both sitting in a café, without talking, while he quietly observed her. It was later, a day before the New Year, that Kechiche decided to offer Exarchopoulos the leading role in the film; as he said in an interview, "I chose Adèle the minute I saw her. I had taken her for lunch at a brasserie. She ordered lemon tart and when I saw the way she ate it I thought, 'It's her!'"[19][22][23]

On the other hand, Léa Seydoux was cast for the role of Emma, ten months before principal photography began in March 2012. Kechiche felt that Seydoux "shared her character's beauty, voice, intelligence and freedom" and that she has "something of an Arabic soul". He added on saying, "What was decisive during our meeting was her take on society: She's very much tuned in to the world around her. She possesses a real social awareness, she has a real engagement with the world, very similar to my own. I was able to realise to how great an extent, as I spent a whole year with her between the time she was chosen for the role and the end of shooting." Speaking to Indiewire on the preparation for her role, Seydoux said "During those ten months (before shooting) I was already meeting with him (Kechiche) and being directed. We would spend hours talking about women and life; I also took painting and sculpting lessons, and read a lot about art and philosophy."[19][23]

Filming

Initially planned to be shot in two and a half months, the film took five, from March to August 2012 for a budget of €4 million.[4] Seven hundred and fifty hours of dailies were shot.[24] Shooting took place in Lille as well as Roubaix and Liévin.[25]

In terms of cinematography, the shot reverse shot scenes in the film were simultaneously shot with two different cameras. For Kechiche this technique not only facilitates editing but also adds beauty to the scene which feels more truthful.[26] Another characteristic aspect of Blue's cinematography is the predominance of close-ups.

Controversies

Upon its premiere at the 2013 Cannes Festival, a report from the French Audiovisual and Cinematographic Union (Syndicat des professionnels de l'industrie de l'audiovisuel et du cinéma) criticised the working conditions from which the crew suffered. According to the report, members of the crew said the production occurred in a "heavy" atmosphere with behaviour close to "moral harassment", which led some members of the crew and workers to quit.[4] Further criticism targeted disrupted working patterns and salaries.[27] Technicians accused director Abdellatif Kechiche of harassment, unpaid overtime and violations of labour laws.[28]

In September 2013, the two main actresses, Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulos, also complained about Kechiche's behaviour during the shooting. They described the experience as "horrible", and said they would not work with him again.[29] Exarchopoloulos later said about the rift: "No, it was real, but it was not as big as it looks. For me, a shoot is a human adventure, and in every adventure you have some conflict."[30] In an interview in January 2014, Seydoux clarified: "I'm still very happy with this film. It was hard to film it and maybe people think I was complaining and being spoilt, but that's not it. I just said it was hard. The truth is it was extremely hard but that's OK. I don't mind that it was hard. I like to be tested. Life is much harder. He's a very honest director and I love his cinema. I really like him as a director. The way he treats us? So what!"[31]

In an interview in September 2013, director Abdellatif Kechiche stated that the film should not be released. Speaking to French magazine Télérama, Kechiche said "I think this film should not go out; it was too sullied", referring to the negative press about his on-set behaviour.[32][33]

Themes and interpretations

Sexuality

Lesbian sexuality is one of the strongest themes of the film, as the narrative deals mainly with Adele’s exploration of her identity in this context. However, the film's treatment of lesbian sexuality has been questioned by academics, due to its being directed from a straight, male perspective. In Sight & Sound, film scholar Sophie Mayer suggests that in Blue is the Warmest Colour, "Like homophobia, the lesbian here melts away. As with many male fantasies of lesbianism, the film centres on the erotic success and affective failures of relations between women".[34] The issue of perspective has also been addressed in a Film Comment review by Kristin M. Jones who points out that "Emma's supposedly sophisticated friends make eager remarks about art and female sexuality that seem to mirror the director’s problematic approach toward the representation of women".[35]

Social class

One recurring thematic element addressed by critics and audiences is the division of social class and the exploration of freedom and love between the two central characters, Adèle and Emma.[36][37] The reference to social class is juxtaposed between the two dinner table scenes in the film, with Adèle's conservative middle-class family engaging in discussion over comparatively banal subjects to Emma's more open-minded upper-middle-class family, who focus their discussion primarily on more existential matters: art, career, life and passion. Perhaps one of the most significant differences between Adèle's and Emma's families is that Emma's is aware of their lesbian relationship, while Adèle's conservative parents are under the impression the women are just friends.[38] Some critics have noted that the difference of social class is an ongoing theme in Kechiche's filmography: "As in Kechiche's earlier work, social class, and the divisions it creates, are a vital thread; he even changed the first name of the story's passionate protagonist from Clémentine to that of his actress, partly because it means "justice" in Arabic. His fascination and familiarity with the world of pedagogy, as shown here in Adèle's touching reverence for teaching, is another notable characteristic", was noted by a Film Comment critic.[39]

Realism

The film portrays Adele and Emma's relationship with an overarching sense of realism. The camerawork, along with many of Kechiche's directorial decisions allow a true-to-life feel for the film, which in turn has led to audiences reading the film with meaning that they can derive from their own personal experiences. In The Yale Review, Charles Taylor puts this into words: "Instead of fencing its young lovers within a petting zoo... Kechiche removes the barriers that separate us from them. He brings the camera so close to the faces of his actresses that he seems to be trying to make their flesh more familiar to us than his own."[40]

Significance of the colour blue

Blue Is the Warmest Colour is also filled with visual symbolism.[41][42] The colour blue is used extensively throughout the film—from the lighting in the gay club Adèle visits, to the dress she wears in the last scene and most notably, in Emma's hair and eyes. For Adèle, blue represents an envoy of curiosity, ecstasy, love and ultimately, sadness. Adèle also references Pablo Picasso a number of times,[43][44] who famously went through a melancholy Blue Period. As Emma grows out of her relationship with Adèle and their passion wanes, she removes the blue from her hair and adopts a more natural, conservative hairstyle.[45] There is also a profusion of imagery of food in the film, from the regularly consumed spaghetti to Adèle's first experience tasting oysters.[46] Relationships—both heterosexual and homosexual—are also a common dynamic throughout the film: from Adèle's exploration of failed first romance with Thomas, to her affair with a male colleague, and to her love and loss with Emma.

Food

Kechiche explores how food can evoke varying levels of symbolism for instance, through sexually ‘suggestive food metaphors – the appetitive Adèle likes the fat on ham, and learns to eat oysters via Emma’.[47] Additionally he looks at how food can be seen as an indicator of social class, ‘cooking her father’s bolognese as the pièce de résistance for Emma’s graduation party offers a neat class observation; inevitably, however, the dripping spaghetti becomes the pivot for a flirtation with Emma’s friend Samir, positioned as a potential future partner by the film’s end.’[47]

Music

One reviewer noted the political stance adopted by Adèle, which changes as her life experiences change and reflect her alternating views: "Blue is the Warmest Colour is no different; at least, at first. Framed by black and Arab faces, Adèle marches in a protest to demand better funding for education. The music, "On lâche rien" ("We will never give up!"), by the Algerian-born Kaddour Haddadi, is the official song of the French Communist Party. Yet, soon after she begins her relationship with Emma, we see Adèle marching again, hip-to-hip with her new lover, at a gay pride parade."[48]

Distribution

Release

Blue Is the Warmest Colour had its world premiere at the 66th Cannes Film Festival on 23 May 2013. It received a standing ovation and ranked highest in critics' polls at the festival.[49] In August 2013, the film had its North American premiere at the 2013 Telluride Film Festival and was also screened in the Special Presentation section of the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival on 5 September 2013.[50]

The film was screened at more than 131 territories[51] and was commercially released on 9 October 2013 in France with a "12" rating.[52] In the United States, the film was rated NC-17 by the Motion Picture Association of America for "explicit sexual content". It had a limited release at four theatres in New York City and Los Angeles on 25 October 2013, and expanded gradually in subsequent weeks.[53][54][55][56] The film was released on 15 November 2013 in the United Kingdom[57] and in Australia and New Zealand on 13 February 2014.[58][59][60]

Home media

La Vie d'Adèle – Chapitres 1 & 2 was released on Blu-ray Disc and DVD in France by Wild Side on 26 February 2014, and in North America, as Blue is the Warmest Color through The Criterion Collection on 25 February 2014.[61] As Blue Is the Warmest Colour, the film was also released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc in Canada on 25 February 2014 by Mongrel Media, in the United Kingdom on 17 March 2014 by Artificial Eye and on 18 June 2014 in Australia by Transmission Films.

In Brazil, Blu-ray manufacturing companies Sonopress and Sony DADC are refusing to produce the film because of its content. The distributor is struggling to reverse this situation.[62]

Reception

Box office

Blue Is the Warmest Colour grossed a worldwide total of $19,492,879.[5] During its opening in France, the film debuted with a weekend total of $2.3 million on 285 screens for a $8,200 per-screen average. It took the fourth spot in its first weekend, which was seen as a "notably good showing because of its nearly three-hour length".[63][64] The film had a limited release in the U.S, and it grossed an estimated $101,116 in its first weekend, with an average of $25,279 for four theatres in New York City and Los Angeles.[65]

Critical response

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 90% based on 167 reviews and an average score of 8.2/10. The site's critical consensus is: "Raw, honest, powerfully acted, and deliciously intense, Blue Is the Warmest Colour offers some of modern cinema's most elegantly composed, emotionally absorbing drama."[66] On Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 based on reviews from mainstream critics, the film has a score of 88 averaged from 41 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[67]

At Cannes, the film shocked some critics with its long and graphic sex scenes (although fake genitalia were used),[68][29] leading them to state that the film may require some editing before it is screened in cinemas.[69] Several critics placed the film as the front-runner to win the Palme d'Or and it went on to win the coveted prize.[13][69][70][71][72] The judging panel, which included Steven Spielberg, Ang Lee, and Nicole Kidman, made an unprecedented move to award the top prize to the film's two main actresses along with the director. Jury president Steven Spielberg explained:

The film is a great love story that made all of us feel privileged to be a fly on the wall, to see this story of deep love and deep heartbreak evolve from the beginning. The director did not put any constraints on the narrative and we were absolutely spellbound by the amazing performances of the two actresses, and especially the way the director observed his characters and just let the characters breathe.[73][74]

Justin Chang, writing for Variety, said that the film contains "the most explosively graphic lesbian sex scenes in recent memory".[3] Jordan Mintzer of The Hollywood Reporter said that despite being three hours long, the film "is held together by phenomenal turns from Léa Seydoux and newcomer Adèle Exarchopoulos, in what is clearly a breakout performance".[75]

Writing in The Australian, David Stratton said, "If the film were just a series of sex scenes it would, of course, be problematic, but it's much, much more than that. Through the eyes of Adèle we experience the breathless excitement of first love and first physical contact, but then, inevitably, all the other experiences that make life the way it is ... All of these are beautifully documented.[76]

In The Daily Telegraph, Robbie Collin awarded the film a maximum of five stars and tipped it to win the Palme d'Or. He wrote: "Kechiche’s film is three hours long, and the only problem with that running time is that I could have happily watched it for another seven. It is an extraordinary, prolonged popping-candy explosion of pleasure, sadness, anger, lust and hope, and contained within it – although only just – are the two best performances of the festival, from Adèle Exarchopolous and Léa Seydoux."[77] Writing for The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw added that "it is genuinely passionate film-making" and changed his star rating for the film to five out of five stars after previously having awarded it only four.[7][78] Stephen Garrett of The New York Observer said that the film was "nothing less than a triumph" and "is a major work of sexual awakening".[79]

Andrew Chan of the Film Critics Circle of Australia writes, "Not unlike Wong Kar-wai's most matured effort in cinema, Happy Together, director Abdellatif Kechiche knows love and relationship well and the details he goes about everything is almost breathtaking to endure. There is a scene in the restaurant where two meet again, after years of separation, the tears that dwell on their eyes shows precisely how much they love each other, yet there is no way they will be together again. Blue Is the Warmest Colour is likely to be 2013's most powerful film and easily one of the best."[80]

Movie Room Reviews praised the film giving it 4 1⁄2 stars saying "This is not a movie that deals with the intolerance of homosexuality or what it’s like to be a lesbian. It’s about wanting to explore that piece of yourself you know is there while still dealing with the awkwardness of youth."[81]

The film was not without its criticisms, many of them about the sex scenes. Manohla Dargis of The New York Times described the film as "wildly undisciplined" and overlong and wrote that it "feels far more about Mr. Kechiche's desires than anything else".[82][83]

Though source author Julie Maroh praised Kechiche's originality, describing his adaptation as "coherent, justified and fluid ... a masterstroke",[84] she also felt that he failed to capture the lesbian heart of her story, and disapproved of the sex scenes. In a blog post, she called the scenes, "a brutal and surgical display, exuberant and cold, of so-called lesbian sex, which turned into porn, and me feel very ill at ease", saying that in the movie theatre, "the heteronormative laughed because they don't understand it and find the scene ridiculous. The gay and queer people laughed because it's not convincing, and found it ridiculous. And among the only people we didn't hear giggling were the potential guys too busy feasting their eyes on an incarnation of their fantasies on screen". She added that "as a feminist and lesbian spectator, I cannot endorse the direction Kechiche took on these matters. But I'm also looking forward to hearing what other women will think about it. This is simply my personal stance."[85]

Conversely, Richard Brody, writing in The New Yorker about "Sex Scenes That Are Too Good", stated: "The problem with Kechiche’s scenes is that they're too good—too unusual, too challenging, too original—to be assimilated ... to the familiar moviegoing experience. Their duration alone is exceptional, as is their emphasis on the physical struggle, the passionate and uninhibited athleticism of sex, the profound marking of the characters' souls by their sexual relationship."[86]

More than 40 critics named the film as one of the ten best of 2013.[87]

Accolades

The film won the Palme d'Or at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival.[14] The actresses were also given the Palme as a special prize.[88][89][90] Kechiche dedicated the award to "the youth of France" and the Tunisian revolution, where "they have the aspiration to be free, to express themselves and love in full freedom".[91] At Cannes it also won the FIPRESCI Prize.[92] In addition, this is also the first film adapted from either a graphic novel or a comic to win the Palme d'Or.[84] In December 2013 it received the Louis Delluc Prize for best French film in 2013.[93] The film was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film award at the 71st Golden Globe Awards and the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language.[15] At the 39th César Awards, the film received eight nominations with Exarchopoulos winning the César Award for Most Promising Actress.[94][95]

See also

References

- ↑ "Blue Is the Warmest Colour (18)". Artificial Eye. British Board of Film Classification. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ "La vie d'Adèle". LUMIERE. European Audiovisual Observatory. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Cannes Film Review: 'Blue Is the Warmest Color'". Variety. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 Fabre, Clarisse (24 May 2013). "Des techniciens racontent le tournage difficile de "La Vie d'Adèle"". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Blue Is the Warmest Color (NC-17)". BoxOffice®. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ (French) Julie Maroh, Le bleu est une couleur chaude, Glénat – Hors collection, 2010, ISBN 978-2-7234-6783-4

- 1 2 Bradshaw, Peter (24 May 2013). "Cannes 2013: La Vie D'Adèle Chapitres 1 et 2 (Blue is the Warmest Colour) – first look review". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Cannes-Winning Stars of 'Blue is the Warmest Color' Talk Controversy, Kechiche: "It's a Blind Trust"". Indiewire. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ "Timeline: A brief history of the drama surrounding Blue is the Warmest Color". Vulture.com. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ "This is not lesbian pornography: Blue is the Warmest Color, defended". deadspin.com. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Emily (24 October 2013). "Did a director push too far?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ "The Blue is the Warmest Colour feud and more actresses who were tortured by directors". The Daily Beast. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Cannes Film Festival: Awards 2013". Cannes. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Blue is the warmest colour team win Palme d'Or at Cannes 2013". Radio France Internationale. 26 May 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- 1 2 Thrower, Emma (13 December 2013). "Golden Globe Award Nominees". The Hollywood News. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ "The top 30 films of 2013". The Times. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "Top 10 films of 2013: From Blue is the Warmest Colour". Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Color". Metacritic. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 "An interview with Abdellatif Kechiche director of Cannes winner Blue Is the Warmest Colour". The Upcoming. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, Charles. "Film in Review." The Yale Review Volume 102, Issue 3, Article first published online: 19 JUN 2014.

- ↑ "What really happened on the Blue is the Warmest Colour set". Daily Life. 8 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ "Cannes Roundtable: Adèle Exarchopoulos on Blue is the Warmest Colour". CraveOnline. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- 1 2 "It Was Just You, Your Skin, And Your Emotion": Lea Seydoux & Adèle Exarchopoulos Talk 'Blue Is The Warmest Color". Indiewire. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ "La Vie d'Adèle", la Palme de l'émotion – letemps.ch

- ↑ "Un film tourné et coproduit en Nord–Pas de Calais en compétition officielle du Festival de Cannes" (PDF). Crrav.com. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- ↑ Interview with Abdellatif Kechiche. Cahiers du Cinema. Octobre 2013. pp. 10-16

- ↑ Fabre, Clarisse (23 May 2013). "Le Spiac-CGT dénonce les conditions de travail sur le tournage de 'La Vie d'Adèle'". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Polémique autour du tournage de la «Vie d’Adèle», La Croix, 29 May 2013.

- 1 2 "The Stars of 'Blue is the Warmest Color' On the Riveting Lesbian Love Story". The Daily Beast. 1 September 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ "Tangled up in Blue is the Warmest Colour". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "L'agent provocateur: meet Léa Seydoux, star of Blue is the Warmest Colour". London Evening Standard. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Patches, Matt (24 September 2013). "'Blue Is the Warmest Color' Shouldn't Be Released, Director Says". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Polémique autour de "La vie d'Adèle" : Abdellatif Kechiche s'explique dans "Télérama"". Télérama. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Review: Blue is the Warmest Colour. Sight and Sound. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ↑ Review: Blue Is the Warmest Color. Film Comment. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Color is about class, not just sex". 4 November 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Color". Icon Cinema. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Film Review: 'Blue Is The Warmest Color'". Neon Tommy. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "Review: Blue is the Warmest Colour". Film Comment. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Everybody's Adolescence "The Yale Review". Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Colour - film review". Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Blue Is the Warmest Color author: "I'm a feminist but it doesn't make me an activist"". Salon. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "Blue Is the Warmest Color". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ "'Blue Is the Warmest Colour' Review - Garry Arnot". The Cult Den. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ "Feeling Blue: On Abdellatif Kechiche's "Blue Is the Warmest Color"". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ "'Blue is the Warmest Color' a masterpiece". Times Union. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- 1 2 Sophie Mayer (2015-02-20). "Blue is the Warmest Colour review | Sight & Sound". BFI. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- ↑ Wolff, Spencer (8 November 2013). "Buried in the Sand: The Secret Politics of Blue is the Warmest Color". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "Lesbian romance 'Blue Is the Warmest Color: The Life of Adèle' wins Palme d'Or, Cannes Film Festival's top honor". Daily News. New York. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Festival - Special Presentation". TIFF. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Color sets out to conquer the world". Unifrance. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "NYFF Film 'Blue Is the Warmest Color' Heads to U.S. with NC-17 Rating". Filmlinc. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Kaufman, Amy (27 October 2013). "Controversial 'Blue Is the Warmest Color' off to solid start". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ↑ Kilday, Gregg (20 August 2013). "'Blue Is the Warmest Color,' Palme d'Or-Winning Lesbian Love Story, Gets NC-17 Rating". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "Palme d'Or winner 'Blue Is the Warmest Color' gets NC-17 rating". Hitfix. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "Blue Is the Warmest Color' To Be Released With NC-17 Rating in U.S.". Variety. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Colour release 'should be cancelled', says director". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Blue Is The Warmest Color". Palace Cinemas. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ "More than sex to lesbian love story Blue is the Warmest Colour". The Australian. 8 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Movie review: Blue Is The Warmest Colour". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Blue is the Warmest Color Product Page". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Conteúdo de 'Azul é a cor mais quente' dificulta lançamento em blu-ray no Brasil". O Globo (in Portuguese). 25 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "FRANCE: 'Planes' Takes Off with $4.2M Debut". BoxOffice. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Richford, Rhonda (23 October 2013). "'Blue Is the Warmest Color' Director Slams 'Arrogant, Spoiled' Star in Open Letter". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Specialty Box Office: Big Debut For 'Blue' As Lesbian Drama Turns Controversy Into Cash". Indiewire. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Blue Is The Warmest Color (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Blue Is the Warmest Color Reviews". Metacritic. CBS. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ Cannes 2013 : les scènes les plus sexe du Festival – Le Figaro

- 1 2 "Lesbian drama tipped for Cannes' Palmes d'Or prize". BBC News. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Ten-Minute Lesbian Sex Scene Everyone Is Talking About at Cannes". Vulture. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Higgins, Charlotte (24 May 2013). "Blue is the Warmest Colour installed as frontrunner for Palme d'Or". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Best Film at Cannes Is the French, Lesbian Answer to Brokeback Mountain". The Atlantic. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Palme d'Or Winner: Cannes Has the Hots for Adèle". Time. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ Badt, Karin (26 May 2013). "Steven Spielberg and Jury Discuss the Winners of Cannes". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ Mintzer, Jordan (24 May 2013). "Blue Is the Warmest Color: Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Stratton, David (8 February 2014). "More than just sex to lesbian love story Blue is the Warmest Colour". The Australian. Sydney. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Cannes 2013: Blue is the Warmest Colour, review". The Daily Telegraph. 24 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ "Blue Is the Warmest Colour – review". The Guardian. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Cannes: Ebullient Lesbian Romance Blue Is the Warmest Color Is Stark Contrast to Dour Nebraska". The New York Observer. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Andrew Chan (23 December 2013). "Blue Is the Warmest Colour". [HK Neo Reviews].

- ↑ "Jostling for Position in Last Lap at Cannes". Movie Room Reviews. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla (23 May 2013). "Jostling for Position in Last Lap at Cannes". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla (25 October 2013). "Seeing You Seeing Me". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- 1 2 Maroh, Julie (27 May 2013). "Le bleu d'Adèle". juliemaroh.com (in French). Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Weisman, Aly (29 May 2013). "The Film That Won Cannes Is Being Blasted By Its Writer As 'Porn'". Business Insider. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Brody, Richard (4 November 2013), "The Problem with Sex Scenes That Are Too Good", The New Yorker, retrieved 10 May 2014

- ↑ "Best of 2015: Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Chang, Justin (26 May 2013). "Cannes: 'Blue Is the Warmest Color' Wins Palme d' Or". Variety. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla (26 May 2013). "Story of Young Woman's Awakening Is Top Winner". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ "Cannes Film Festival: Lesbian drama wins Palme d'Or". BBC News. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Pulver, Andrew (26 May 2013). "Cannes 2013 Palme d'Or goes to film about lesbian romance". The Guardian UK. London. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ Richford, Rhonda (26 May 2013). "Cannes: 'The Missing Picture' Wins Un Certain Regard Prize". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ↑ "'Blue Is The Warmest Color' Wins Gaul's Louis Delluc Award". Variety. 17 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ↑ "Me, Myself and Mum, Blue Is the Warmest Color Top Noms For France's Cesar Awards". Variety. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Richford, Rhonda. "France's Cesar Awards: 'Me, Myself and Mum' Wins Best Film". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La Vie d'Adèle. |

- Official website

- Blue Is the Warmest Colour at the Internet Movie Database

- Blue Is the Warmest Color at Box Office Mojo

- Blue Is the Warmest Color at Rotten Tomatoes

- Blue Is the Warmest Color at Metacritic

- Cannes Film Festival press kit