Batterie Mirus

The Batterie Mirus is located in Saint Peter and Saint Saviour, Guernsey. Originally called Batterie Nina, it comprised four 30.5 cm guns. The battery was constructed from November 1941 and through the first half of 1942, it was the largest battery in the Channel Islands, the guns having a maximum range of 51 km. The guns were removed in the early 1950s however the reinforced concrete structures and associated positions remain intact.

Planning

In 1940 it was initially agreed that the defence of the Channel Islands would come under the remit of the German Kriegsmarine, so Marine Artillerie Abteilung 604 (MAA604) was dispatched to set up a battery on each of the principal islands with calibers of 22 cm, 17 cm and 15 cm. These were installed by May 1941.[1]:11

On 2 June 1941 Adolf Hitler asked for maps of the Channel Islands. By 13 June Hitler had made a decision. Ordering additional men to the Islands and having decided the defences were inadequate, lacking tanks and coastal artillery, the Organisation Todt (OT) was instructed to undertake the building of 200-250 strongpoints in each of the larger islands. The Westbefestigungen (Inspector of Western Fortresses) was put in overall command, and reports would be made every two weeks of progress.[2]:190–3

After visits to the islands by Dr Todt, the OT plan, was finalised and submitted to Hitler.[3] The original defence order was reinforced with a second dated 20 October 1941, following a Führer conference on 18 October to discuss the engineers assessment of requirements.[2]:197 Referring to the “permanent fortification” of the Channel Islands to make an impregnable fortress to be completed by December 1942.[4]:448

The plan had required three batteries of 38 cm guns be based on the islands to also provide protection for the bay of Saint-Malo, however they could not be supplied. It was at this conference that the proposal for the 30.5 cm Batterie Nina was approved as four guns and 1,000 rounds of ammunition could be provided at short notice.[1]:13–14 The work would continue as planned, despite the death of Dr Todt, who was also Minister of Armaments, in a plane crash in February 1942. He was replaced by Albert Speer.

Barrels

The 15.85 meters long barrels were cast at the Obuchov foundry in 1914 and became the main armament for one of a series of dreadnoughts of the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet.[5]

A Finnish ship, SS Nina was captured at Narvik during the German invasion of Norway. On board was found four barrels from the Russian battleship Imperator Aleksandr III. This 1914 ship, had been surrendered by the White Fleet in 1921 and interned in Bizerta, where for non-payment of harbour dues she was sold for scrap in the late 1920s, although she was only broken up in 1936. The 12 main armament barrels were placed in storage in Bizerta before being given to Finland in 1940. Eight reached Finland, the remaining four were on board SS Nina when the ship was seized by the Germans.[6]

The captured barrels were sent to Germany, where they were taken to Krupp at Essen where land based mounts were designed and constructed. With a potential range of 51,000m with 250 kg high-explosive shells, and 32,000m with the heavier 405 kg armour-piercing or high-explosive shells they would make good shore based guns.[7]

The barrels were given the designation 30.5cm K.14(r) (“14” meaning 1914, year of manufacture) (“r” meaning russisch or Russian). The original cradles for the guns provided elevation to only 15º, so new electrically driven mounting platforms, weighing 38,190 kg, were designed and built enabling an elevation of 48º. They would be known as the Bettungsschiessgerüst C.40 mounts.[1]:20

The shells were propelled with cordite at up to 1,020m/sec, and a compressed air system was developed to allow for the barrels to be cleaned after each round.[1]:21 By 1941, the work on mounts was sufficiently well advanced to commence work on the armour plating of the guns, 150mm at the front, and 50mm on the sides, top and rear.[7] New ammunition was also manufactured by Krupp.[6]

The barrels and their cradles were transported on trains to Saint Malo and one at a time put on a barge to Saint Peter Port Harbour Guernsey. A large 100 ton Dutch floating crane was towed from Le Havre, it was needed to lift each 51 ton barrel and breach and 38 ton mounting from the barge onto a trailer with 48 tyres on 12 steerable axles. This trailer, carrying just one piece of a gun was then pulled 8 km at walking speed using four heavy Sd.Kfz. 8 half-tracks connected in line to the battery site. Preparations for the transport in Guernsey included taking trees down with several junctions having walls demolished so that the convoy could avoid sharp corners. 75 ton gantries would lift the guns into their emplacements.[1]:24–31

Construction

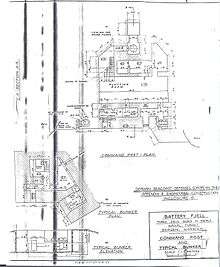

The four gun battery was scattered over an area 1 km x 0.75 km. Some local civilians were evicted during the construction period, others after it was completed. Roads were closed and access restricted.[1]:35

A work camp for the OT workers was built, Lager Westmark, many of the workers, were Republican Spanish who had fled Franco and who had been collected from internment camps in France. They were badly fed and treated by the civilian German construction companies they worked for.[8] Other workers included specialist experts brought to the island from Germany or occupied countries and Guernsey men. All workers were paid for their work.[9]:168 [10]

If British aircraft were near, the Germans would cut all the lights at their building sites, but not the power to the concrete mixers. The huge mixers ran night and day. 45,000m³ of concrete was poured into the battery area.[6] After they had been built, the battery they covered with earth again.[8] Despite the care, Allied flights over the island had photographed the construction sites.[11]

Apart from the gun positions, the battery comprised:

- Command bunker leitstand (type S446) underground, with observation cupola and 10m wide stereoscopic rangefinder [12]

- Accommodation bunker underground, attached to command bunker[13]

- Wurzburg radar built on the base of a Flak 29 emplacement in April 1944 [12]

- Four Flak 38 and five Flak 29 & Oerlikon 20mm L/85 anti-aircraft gun on towers (type F1242) above bunkers for flak crews

- Three reserve ammunition bunkers above ground with 60 cm light trolly tracks (type S448a)

- A mess hall was built above ground in the centre of the battery.[13]

- Underground water storage tank

Mirus was the only battery in the Channel Islands that had its own Wurzburg radar.[1]:16

The command centre of the battery was linked by telephone lines to naval headquarters, Seeko-Ki at St Jacques, in St Peter Port and from there to each naval range finding tower, MP1 (facing north) at Chouet, MP2 (facing North-West at L’Eree, MP3 (facing west) and MP4 (facing south) located on cliff tops at Pleinmont. Each level of each tower being connected to, and sighting for, a different naval battery using range finding equipment and Freya radar mounted on the roof of each tower. Seeko-Ki used a grid system to indicate target areas for the batteries.[1]:16

Apart from the close support (<1,000m) 20mm anti aircraft guns, the battery received support from air attack from the six 8.8cm Flak batteries on the island. Three 60 cm and two 150cm searchlights provided night time illumination.[1]:72

Landings from sea or air landing assault were protected by coastal defences and by infantry and a panzer tank unit located inland. Close to the battery were two 8.1 cm and three 5 cm mortar positions, three 7.5cm FK 231(f) field artillery guns, 16 concrete machine gun positions, barbed wire and mines which gave all round protection.[14]

All accommodation bunkers produced using the standard Regelbau system were protected against gas attack with air tight doors, ventilation and filtration systems.

Gun casemate

Each of the four gun positions comprised the following:

- 21m circular concrete pit to provide a base for a turret comprising central pin, inner walkway (to take the breech recoil when gun operating at maximum elevation), thin middle wall 1.54m high, outer walkway, outer 1.5m thick 2.7m high blast wall

- Armoured turret, which could be rotated to allow the gun to turn 360 degrees

- At the rear of the circular pit is the 1.5m thick blast wall with two entrances, one on each side. The forward section of the emplacement being disconnected from the rear section to reduce concussion when the gun was fired

- Entrance ramp with light trolley track to bring in ammunition and supplies

- light trolley tracks run to ready stores, one for cordite and the other for the projectile behind the circular blast wall

- Two cordite stores, with reinforced concrete walls and a steel rocker delivery system that was used to deliver one 80 kg cordite charge at a time to the gun. (4.6m x 7.75m)

- Ammunition projectile store containing shells (4.5m x 12.6m)

- Ventilation room (3.0m x 7.7m)

- Generator room (4.6m x 10.8m)

- Fuel store (3.0m x 3.5m)

- Heating plant (3.1m x 3.4m)

- Officers command and sleeping quarters

- Crew sleeping quarters 4 x (3.6m x 8.5m)

- NCO sleeping quarters

- Shower, toilet and washing facilities

- Store rooms

- Rear entrance

The rear section measures externally 33m long by 31m wide, the external walls are 1.5m thick, the roof over the rear section being 2.7m thick.

Camouflage was used in the battery, part burying a number of bunkers was common. Guns No. 1 and 3 were disguised as cottages whilst No.2 and No. 4 used netting and fake trees and bushes as camouflage.[1]:52 The three reserve ammunition bunkers, which were built above ground, were camouflaged as houses, given pitched roofs and painted windows and doors.[14]

Operations

A naval crew of 72 men manned each gun and on 13 April 1942 the first test firing of gun No. 2 took place.[7]

The April demonstration was witnessed by several observers, including an official photographer, who stood too close and was thrown into a ditch by the concussion.[1]:50 Before test firing local house owners were warned to open windows to avoid the glass shattering. Greenhouses in the area collapsed or lost many panes of glass every time the guns were fired.[8] By 29 June, all four guns were in operation, and were ready for manual operation.[7]

The command centre used a mechanical computer, which took into account details of wind speed, air pressure and firing range. The data instrument computed these results. Corrections were made depending if the shots were short or over. The control room was manned twenty-four hours a day and required a crew of 18 working shifts.[12]

In August 1942 a short ceremony was held to rename the battery. On the orders of Großadmiral Erich Raeder it became Batterie Mirus in honour of Kapitän zur See Rolf Mirus, a Kriegsmarine weapons expert killed in action on 3 November 1941 aboard Flugsicherunggsboot 502 travelling from Guernsey to Alderney.[1]:53

It was 1 November when the mechanisation of the battery was complete. It was then formally handed over to the Kriegsmarine and came under the remit of MAA604.[7] Work continued on the site with ancillary works being constructed in the ensuing months.

Regular alerts took place, some for practice and some for real, however not all alerts resulted in the guns being fired. Sometimes British naval vessels would approach Guernsey to try to get the guns to fire so they could estimate the range and accuracy of these guns, these tests were often ignored and British ships were allowed to enter well within the effective range of the guns.[7]

One real shoot on 2 November was found to be targeting two British barrage balloons which had drifted in the sea NW of Guernsey and gave “strange” radar readings on five radar sets. Along with seven other smaller batteries, 529 rounds in total were fired with no effect.[7]

In 1943, the battery opened fire on a target, Gun no. 4 broke its trunion rings after two rounds and Gun no. 3 suffered the same fate one round later. Gun no.1 was also put out of action due to a damaged recoil mechanism, the guns had been firing 250 kg HE shells using a 71 kg cartridge at 31º. Engineers were flown in, spare parts were sourced from the Baltic and repairs were completed within the month.[7] The armour plating on the turret roof was improved to 150mm during the repair period.[1]:80 Risk of damage was always a factor in deciding whether to fire, as was the limited life span of the barrels which would need to be returned to the factory to have the internal grooved bore replaced.[1]:19

Mirus was called into action on D-Day, attacking naval units patrolling off of the Cotentin peninsula, damaging two vessels from the resulting blast of a near miss from one 30.5 cm shell. Thereafter, Allied ships were ordered to kept their distance, even so a number of incidents of destroyers coming too close resulted in a salve being fired from Mirus.[1]:85–90

Each gun could fire a shell every 60–90 seconds, depending on the elevation.[1]:21 The guns were used for Nazi propaganda purposes in photos and in films.[7]

On 8 May 1945, following the announcement of the official surrender of Germany, Admiral Friedrich Hüffmeier, the Garrison Commander of the Channel Islands warned the Royal Navy that he would fire the coastal batteries at two destroyers, HMS Beagle escorting HMS Bulldog, which had come to accept the surrender, unless they withdrew until the official surrender time of one minute past midnight on 9 May 1945.[15]:296

Command structure

The Channel Island naval commander, Kommandant der Seeverteidigung Kanalinseln was created in June 1942, Kapitän-zur-See Julius Steinbach, was based at St Jacques in Guernsey, where a Naval command centre abbreviated to Seeko-Ki was built. The Island commander reported to the Admiral in charge of the French coast in Rouen, Admiral Hermann von Fischel.[1]:15

The first commander of the battery arrived in January 1942. Kapitänleutnant Peter Müller, from Bremen. Succeeded by Korvettenkapitän Max Schreiber, a former Chief of Police in the City of Munich. Max Schreiber was extremely popular and became its longest serving commander. Replaced as commander of Mirus by Kapitänleutnant Bruno Heck who was its commander until the German Surrender in May 1945.[7]

The Battery Commander throughout Mirus’ active period was Oberleutnant Hellings. His counterpart in the command post was Oberleutnant Viggerhaus.[7]

A Battery Artillery Officer was directly in charge of all four guns, each with a Turmführer (gun commander), three NCOs and some 68 men manning each gun.[7]

Post-war

When the Allies arrived in Guernsey, the guns were still intact, no orders had been given to sabotage them. The battery personnel were concentrated in local camps before being shipped to the UK as POWs in empty Landing Ship, Tanks.[16]:73

The drive to recover scrap metal and a strong dislike of anything German in the islands saw the metalwork in the battery removed and scrapped from 1947 onwards, this included the armoured cover, doors, hoists, engines etc. with the barrels and mounts cut up in 1952/3.[17]:115

An ex-RAF Coles mobile crane lifted out a depth charge found at Batterie Mirus during the scrap metal drive of the early 1950s. The charge was originally thought to be a large grease drum used in the operation of the gun, camouflaging its true lethal purpose.[16]:125

- There is a plan by Festung Guernsey to open No. 1 gun to the public.[18] It is a protected monument[19]

- Gun No. 2 is on private land and has been filled in.[13]

- Gun No. 3 is located within a school’s grounds.[13]

- Gun No. 4 is on private land and is used for battle games, it is a protected monument[19]

- The mess hall has been converted into holiday cottages.

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Partridge, Colin and Wallbridge, John. Mirus: The Making of a Battery. Ampersand Press (C.I.) Ltd. ISBN 978-0946346042.

- 1 2 Cruickshank, Charles. The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. The History Press; New edition edition (30 Jun. 2004). ISBN 978-0750937498.

- ↑ "History:Fortifying Guernsey". Festung Guernsey.

- ↑ Bell, William. Guernsey Occupied but never Conquered. The Studio Publishing Services (2002). ISBN 978-0952047933.

- ↑ "12"/52 (30.5 cm) Pattern 1907". NavWeaps.

- 1 2 3 Fowler, Will. The Last Raid: The Commandos, Channel Islands and Final Nazi Raid. The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0750966375.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Mirus History". PIGS.

- 1 2 3 "The Guns that Came to Stay" (PDF). St Saviour Parish.

- ↑ Forty, George. Channel Islands At War: A German Perspective. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711030718.

- ↑ Handbook of the Organisation Todt - part 1. Military Intelligence Records Section, London Branch. May 1945.

- ↑ "The National Collection of Aerial Photography".

- 1 2 3 "Mirus Battery Plotting Room" (PDF). St Saviour Parish.

- 1 2 3 4 "Batterie Mirus". Festung Guernsey.

- 1 2 McNab, Chris. Hitler’s Fortresses: German Fortifications and Defences 1939–45. Osprey Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-1782008286.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Charles. The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. The Guernsey Press Co, Ltd.

- 1 2 Channel Islands Occupation Review No 38. Channel Islands Occupation Society. 2010.

- ↑ Channel Islands Occupation Review 35. Channel Islands Occupation Society.

- ↑ "Guernsey WWII site may be opened to public". BBC. 10 March 2011.

- 1 2 "protected monuments". States of Guernsey.

Bibliography

- Partridge, Colin and Wallbridge, John, (1983) ‘’Mirus: The Making of a Battery’’, Ampersand Press (C.I.) Ltd, ISBN 978-0946346042

- Festung Guernsey 2.1 & 2.2: Weapons Deployed and Mirus Battery (Festung Guernsey), (2014), The Clear Vue Publishing Partnership Limited, ISBN 9780992667139