Australia Act 1986

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Australia |

|

|

|

Related topics |

| Australia Act 1986 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliament of Australia | |

| An Act to bring constitutional arrangements affecting the Commonwealth and the States into conformity with the status of the Commonwealth of Australia as a sovereign, independent and federal nation | |

| Citation | Act No. 142 of 1985 |

| Enacted by | Parliament of Australia |

| Date of Royal Assent | 4 December 1985 |

| Date commenced | 3 March 1986 |

| Status: Current legislation | |

|

| |

| Long title | An Act to give effect to a request by the Parliament and Government of the Commonwealth of Australia |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1986 c. 2 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 17 February 1986 |

| Commencement | 3 March 1986 |

Status: Current legislation | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The Australia Act 1986 is the name given to a pair of separate but related pieces of legislation: one an Act of the Commonwealth (i.e. federal) Parliament of Australia, the other an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. While each Act gives its short title as "Australia Act 1986", in Australia they are referred to, respectively, as the Australia Act 1986 (Cth) and the Australia Act 1986 (UK). These nearly identical Acts were passed by the two parliaments, to come into effect simultaneously, because of uncertainty as to which of the two parliaments had the ultimate authority to do so.

The Australia Act (Cth and UK) eliminated the remaining possibilities for the UK to legislate with effect in Australia, for the UK to be involved in Australian government, and for an appeal from any Australian court to a British court.[1]

UK and Australian legislation

The Commonwealth of Australia was formed in 1901 by federation of six British colonies, each of which became a State. The Commonwealth Constitution provided for a Commonwealth Parliament, with legislative power on a range of specified topics, leaving the residue of legislative power to the States. That constitution was (and still is) contained in a British statute.[2] The United Kingdom Parliament retained ultimate legislative power in relation to Australia.

The UK Parliament's power to legislate with effect for the Commonwealth itself was mostly ended with the Statute of Westminster 1931, when adopted by Australia in 1942 retroactive to 1939.[3] The Statute provided (s 4) that no future UK Act would apply to a Dominion (of which Australia was one) as part of its law unless the Act expressly declared that the Dominion had requested and consented to it. Until then, Australia had legally been a self-governing colony of the United Kingdom, but with the adoption of the Statute became a (mostly) sovereign nation.

However, s 4 of the Statute only affected UK laws that were to apply as part of Australian Commonwealth law, not UK laws that were to apply as part of the law of any Australian State. Thus, the Parliament of the United Kingdom still had the power to legislate for the states and territories. In practice, however, this power was almost never exercised. For example, in a referendum on secession in Western Australia in April 1933, 68% of voters favoured seceding from Australia and becoming a separate Dominion. The state government sent a delegation to Westminster to request that this result be enacted into law, but the British government refused to intervene on the grounds that this was a matter for the Australian government. As a result of this decision in London, no action was taken in Canberra or Perth.

The Australia Act ended all power of the UK Parliament to legislate with effect in Australia – that is, "as part of the law of" the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory (s 1). Conversely, no future law of a State would be void for inconsistency with (being "repugnant to") any UK law applying with "paramount force" in Australia; a State (like the Commonwealth) would have power to repeal or amend such an existing UK law so far as it applied to the State (s 3). State laws would no longer be subject to disallowance or suspension by the Queen (s 8) – a power that, anomalously, remains for Commonwealth legislation (Constitution ss 59 and 60).[4]

Government in Australian states

Similarly, the Australia Act removed the power of the British government to be involved in the governing of an Australian State (ss 7 and 10). Specifically, only the State Premier could now advise the Queen on appointment or removal of a State Governor. Nonetheless, the Queen could still exercise any of her powers with respect to the State if she was "personally present" in the State.[5]

Appeals to the Privy Council

At federation in 1901, the supreme court of each colony became the supreme court of that State.

In 1903, a High Court of Australia was established, one of whose functions was to hear appeals from the State supreme courts. The draft of the Constitution, that was put to voters in the various colonies and presented to the British government for embodiment in UK legislation, was that there was to be no appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council in any matter involving the interpretation of the Constitution or of the Constitution of a State, unless it involved the interests of some other dominion.[6] However, the British insisted on a compromise.[7][8] Section 74 of the Constitution as enacted by the Imperial Parliament,[9] provided two possibilities of appeal. There could be an appeal if the High Court issued a certificate that it was appropriate for the Privy Council to determine an inter se matter, i.e. a matter that concerned the constitutional relations between the Commonwealth and one or more States or between two or more States. And there could be an appeal with permission of the Privy Council. The Commonwealth Parliament was empowered to legislate to limit the latter path and it did so in 1968 and 1975;[10][11] but legislation could only limit, not abolish.

Predictably, the High Court proved reluctant to grant certificates for appeal to the Privy Council. The discretion was exercised only once, in 1912.[12] In 1961, delivering on behalf of the whole Court a brief dismissal of an application for a certificate, Chief Justice Sir Owen Dixon said: "experience shows – and that experience was anticipated when s. 74 was enacted – that it is only those who dwell under a Federal Constitution who can become adequately qualified to interpret and apply its provisions".[13] In 1985, the High Court unanimously observed that the power to grant such a certificate "has long since been spent" and is "obsolete".[14]

Although the path of appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council had been effectively blocked, the High Court could not block appeals from State supreme courts directly to the Privy Council. Nor did the Constitution limit, or provide for legislation to limit, such appeals. The expense of any appeal to the Privy Council in London had been a deterrent: in any year, there had never been more than a handful.[15] Nonetheless, by the 1980s the possibility of appeal from a State supreme court was seen as outdated.

In addition, in 1978 confusion over the relative precedential value of High Court and Privy Council decisions had been introduced when the High Court ruled that it would no longer be bound by Privy Council decisions.[16]

Constitution s 74 has not been amended, and the Constitution cannot be amended by legislation.[4] Nonetheless, s 11 of the Australia Act goes as far as legislatively possible, to make s 74 a dead letter. Thus, for practical purposes, the Australia Act has eliminated the remaining methods of appeal to the Privy Council.[17]

Passage and proclamation of the Act

The plan to revamp both federal and State constitutional arrangements required each State parliament to pass its own enabling legislation. The long title of these State Acts (such as the Australia Acts (Request) Act 1985 of New South Wales) was "An Act to enable the constitutional arrangements affecting the Commonwealth and the States to be brought into conformity with the status of the Commonwealth of Australia as a sovereign, independent and federal nation". The body of each State Act set out the State's "request and consent" as to both the Australian and the UK versions of the Australia Act.

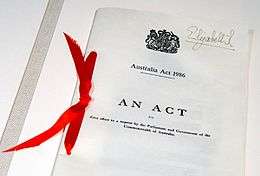

The Governor-General of Australia, Sir Ninian Stephen, assented to the Australia Act (Cth) "In the name of Her Majesty" on 4 December 1985.[18] However, Queen Elizabeth II was to visit Australia early in 1986 and, in acknowledgement of Australian sensibilities, it was arranged that she would assent to both versions of the Act and then proclaim them so that they would come into force at the same moment in both countries. She assented to the Australia Act 1986 (UK) on 17 February 1986 and on 24 February proclaimed that it would come into force at 0500 Greenwich Mean Time on 3 March.[19] Then, visiting Australia, at a ceremony held in Government House, Canberra, on 2 March 1986 the Queen signed a proclamation that the Australia Act (Cth) would come into force at 0500 GMT on 3 March.[20] Thus, according to both UK law and Australian law, the two versions of the Australia Act would commence simultaneously—the UK version at 0500 GMT in the UK and, according to the time difference, the Australian version at 1600 AEST in Canberra.[21] The ceremony was presided over by the Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, to whom Elizabeth presented the signed copy of the proclamation, along with the Assent original of the UK Act (image above).[22]

At the time, the Commonwealth, State and UK Acts were known as the "Australia Acts". However, the State Acts have performed their function and the expression "Australia Act(s)" is now used to refer only to the Commonwealth and UK Acts.

The Act and Australian independence

The principal difference between the Commonwealth and UK versions of the Australia Act lies in the reference, appearing in the long title and preamble to the Commonwealth version but not present in the UK version, to Australia as "a sovereign, independent and federal nation". While this might be understood as a declaration of independence, it can also be understood as an acknowledgement that Australia was already independent, leaving open the question of when independence had been attained. There is no earlier declaration or grant of independence.

The High Court in Sue v Hill in 1999[23] did not rely upon the long title or the preamble, which conventionally do not have force of law. But it decided that the effect of the Australia Act 1986 (Cth) was that, at least from the date when the Act came into operation, Britain had become a "foreign power" within the meaning of Constitution section 44(i), so that a parliamentary candidate who had British nationality was ineligible to be a member of the Commonwealth Parliament.

That view was taken in Sue v Hill by three members of the Court, supported with misgivings by one other member. One of those who did not find it necessary to express an opinion on this point, Justice Michael Kirby, was in a later case to deliver a dissent in which he argued that the Australia Act 1986 (Cth) was invalid.[24] Constitution s 106 guarantees that a State constitution may be altered only in accordance with its own provisions,[25] hence not by the Commonwealth Parliament. However, both versions of the Australia Act contain amendments to the constitutions of Queensland (s 13) and Western Australia (s 14). In Kirby J's view in Marquet (2003),[24] this was inconsistent with Constitution s 106, so that the Australia Act (Cth) was not a valid exercise of Commonwealth legislative power. A majority, however, thought that it was sufficient that the Act had been passed in reliance on Constitution s 51(xxxviii), which gives the Commonwealth parliament power to legislate at the request of the State parliaments.

Soon afterwards, however, in Shaw (2003),[26] the whole Court (including Kirby) took a more comprehensive view: that the Australia Act in its two versions, together with the State request and consent legislation, amounted to establishing Australian independence at the date when the Australia Act (Cth) came into operation, 3 March 1986.

See also

- Australia: Constitution of Australia

- Canada: Canada Act 1982; Constitution Act 1982

- New Zealand: New Zealand Constitution Act 1986

Notes

- ↑ The Australian version has not been amended since; the UK version has been amended only as to an element of UK law, without effect in Australia.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900, referred to in Australia as (UK) or (Imp), for "Imperial". It continues to apply in Australia by "paramount force" or by adoption.

- ↑ Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 (Cth) Federal Register of Legislation; the adoption was backdated, with mainly symbolic effect, to the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

- 1 2 Neither version of the Australia Act could change the Constitution; that can be done only through a national referendum, under Constitution s 128. The referendum process is very difficult; as of 2011, only 8 out of 44 proposals put to referendum have been approved.

- ↑ There is no equivalent provision as to the Commonwealth. However, for both the Commonwealth and the States, constitutional convention effectively excludes the monarch from any personal exercise of governmental power. The 1986 proclamation was an exception, approved by Australian ministers.

- ↑ See for example "Australasian Federation Enabling Act 1899 No 2 (NSW)" (PDF). NSW Parliamentary Council's Office.

- ↑ JA La Nauze (1972). The Making of the Australian Constitution. Melbourne University Press. p. 253.

- ↑ John M Williams (2015). "Ch 5 The Griffith Court". In Dixon, R; Williams, G. The High Court, the Constitution and Australian Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107043664.

- ↑ "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp)" (PDF).

- ↑ Privy Council (Limitation of Appeals) Act 1968 (Cth), which ended all appeals to the Privy Council in matters involving federal legislation

- ↑ Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 (Cth), which prohibited almost all types of appeal from the High Court.

- ↑ Colonial Sugar Refining Co Ltd v Attorney-General (Cth) [1912] HCA 94, (1912) 15 CLR 182.

- ↑ Whitehouse v Queensland [1961] HCA 55, (1961) 104 CLR 635.

- ↑ Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd (No 2) [1885] HCA 27, (1985) 159 CLR 461.

- ↑ AustLII. "Privy Council Appeals". Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ Viro v R [1978] HCA 9, (1978) 141 CLR 88.

- ↑ Appeals were still being lodged up to the last moment. The final such appeal, an equity case from the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, was comprehensively dismissed by the Privy Council on 27 July 1987: Austin v Keele [1987] UKPC 24, CLR.

- ↑ Australia Act 1986 (Cth ) Assent original. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Australia Act (Commencement) Order 1986" (PDF). Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No S 85 of 2 March 1986.

- ↑ Anne Twomey, The Chameleon Crown (2006), 258–9.

- ↑ Elizabeth II as Queen of Australia signs the proclamation. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Sue v Hill [1999] HCA 30, (1999) 199 CLR 462.

- 1 2 Attorney-General (WA) v Marquet [2003] HCA 67, (2003) 217 CLR 545.

- ↑ This would normally be through a referendum of the people of the State.

- ↑ Shaw v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2013] HCA 72, (2003) 218 CLR 28.

References

- Editors, "Sovereignty and independence – Australia – severance of residual links with the United Kingdom – proclamation of the Australia Act 1986" (1984–1987) 11 Australian Year Book of International Law 171-174. Retrieved 15 December 2013

- Twomey, Ann (2010). The Australia Acts 1986: Australia's Statutes of Independence. Annandale: Federation Press. ISBN 978-1-86287-807-5.

- Twomey, Ann (2006). The Chameleon Crown: The Queen and Her Australian Governors. Annandale: Federation Press. ISBN 978-1-86287-629-3.

- Williams; et al., eds. (2014). Blackshield and Williams, Australian Constitutional Law and Theory (6th ed ed.). Annandale: Federation Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-1-86287-918-8.

External links

- Text of the Australia Act 1986 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk .

- Australian official texts:

- Privy Council (Limitation of Appeals) Act 1968 (Cth). Retrieved 3 June 2011

- Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 (Cth). Retrieved 3 June 2011

- Australia Act 1986 (Cth). Retrieved 3 June 2011

- Australia Acts (Request) Act 1985 (NSW). Retrieved 3 June 2011

- Privy Council appeals:

- Privy Council Appeals from Australia (up to 1980 only, from AustLII). Retrieved 5 June 2011

- Privy Council Decisions (complete, from BAILII). Retrieved 5 June 2011

- National Archives of Australia, "Documenting a Democracy":

- "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp)". Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "Australia Act 1986 (Cth)". Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "Queen Elizabeth II signs the Proclamation of the Australia Act (Cth), 1986". Retrieved 3 June 2011.

.svg.png)