Auckland

| Auckland Tāmaki-makau-rau (Māori) | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan city | |

|

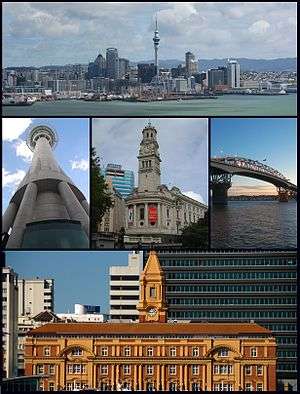

From upper left: Skyline of Auckland City, Sky Tower, Town Hall, Auckland Harbour Bridge, Ferry Building | |

|

Nickname(s): City of Sails Queen City (archaic) | |

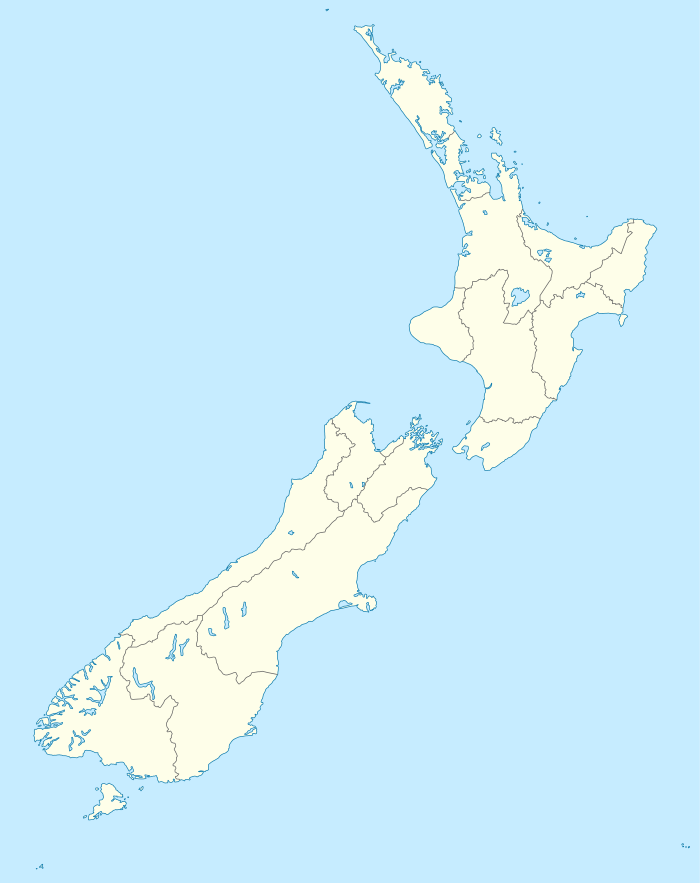

Auckland Auckland is in the North Island of New Zealand | |

| Coordinates: 36°50′26″S 174°44′24″E / 36.84056°S 174.74000°ECoordinates: 36°50′26″S 174°44′24″E / 36.84056°S 174.74000°E | |

| Country |

|

| Island | North Island |

| Region | Auckland |

| Territorial authority | Auckland |

| Settled by Māori | c. 1350 |

| Settled by Europeans | 1840 |

| Local boards |

List

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Phil Goff |

| Area | |

| • Urban[1] | 559.2 km2 (215.9 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 196 m (643 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (June 2016)[2] | |

| • Urban | 1,495,000 |

| • Urban density | 2,700/km2 (6,900/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,614,300 |

| • Demonym | Aucklander |

| Time zone | NZST (UTC+12) |

| • Summer (DST) | NZDT (UTC+13) |

| Postcode(s) | 0600–2699 |

| Area code(s) | 09 |

| Local iwi | Ngāti Whātua, Tainui, Ngati Akarana |

| Website | www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz |

Auckland (/ˈɔːklənd/ AWK-lənd), in the North Island of New Zealand, is the largest and most populous urban area in the country. Auckland has a population of 1,495,000, which constitutes 32 percent of New Zealand's population.[2] It is part of the wider Auckland Region—the area governed by the Auckland Council—which also includes outlying rural areas and the islands of the Hauraki Gulf, resulting in a total population of 1,614,300.[2] Auckland also has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world.[3] The Māori language name for Auckland is Tāmaki, or longer versions such as Tāmaki-makau-rau, meaning "Tāmaki of a hundred lovers", in reference to the desirability of its fertile land at the hub of waterways in all directions.[4] It has also been called Ākarana, the Māori transliteration of the word Auckland.

The Auckland urban area (as defined by Statistics New Zealand) ranges to Waiwera in the north, Kumeu in the northwest, and Runciman in the south. It is not contiguous; the section from Waiwera to Whangaparāoa Peninsula is separate from its nearest neighbouring suburb of Long Bay. Auckland lies between the Hauraki Gulf of the Pacific Ocean to the east, the low Hunua Ranges to the south-east, the Manukau Harbour to the south-west, and the Waitakere Ranges and smaller ranges to the west and north-west. The surrounding hills are covered in rainforest and the landscape is dotted with dozens of dormant volcanic cones. The central part of the urban area occupies a narrow isthmus between the Manukau Harbour on the Tasman Sea and the Waitemata Harbour on the Pacific Ocean. It is one of the few cities in the world to have two harbours on two separate major bodies of water.

The isthmus on which Auckland resides was first settled around 1350 and was valued for its rich and fertile land. Māori population in the area is estimated to have peaked at 20,000 before the arrival of Europeans.[5] After a British colony was established in 1840, the new Governor of New Zealand, William Hobson, chose the area as his new capital. He named the area "Auckland" for George Eden, Earl of Auckland, British First Lord of the Admiralty. It was replaced as the capital in 1865, but immigration to the new city stayed strong and it has remained the country's most populous urban area. Today, Auckland's Central Business District is the major financial centre of New Zealand.

The 2014 Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranked Auckland 3rd place in the world on its list,[6] while the Economist Intelligence Unit's World's most liveable cities index of 2016 ranked Auckland in 8th place.[7] In 2010, Auckland was classified as a Beta World City in the World Cities Study Group's inventory by Loughborough University.[8] In terms of population it is the largest Oceanian city outside Australia.[9]

History

Early history

The isthmus was settled by Māori around 1350, and was valued for its rich and fertile land. Many pā (fortified villages) were created, mainly on the volcanic peaks. Māori population in the area is estimated to have been about 20,000 people before the arrival of Europeans.[5][10] The introduction of firearms at the end of the eighteenth century, which began in Northland, upset the balance of power and led to devastating intertribal warfare beginning in 1807, causing iwi who lacked the new weapons to seek refuge in areas less exposed to coastal raids. As a result, the region had relatively low numbers of Māori when European settlement of New Zealand began. There is, however, nothing to suggest that this was the result of a deliberate European policy.[11][12] On 27 January 1832, Joseph Brooks Weller, eldest of the Weller brothers of Otago and Sydney bought land including the sites of the modern cities of Auckland and North Shore and part of Rodney District for "one large cask of powder" from "Cohi Rangatira".[13]

After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in February 1840 the new Governor of New Zealand, William Hobson, chose the area as his new capital and named it after George Eden, Earl of Auckland, then Viceroy of India.[14] The land that Auckland was established on was given to the Governor by local Maori iwi Ngāti Whātua as a sign of goodwill and in the hope that the building of a city would attract commercial and political opportunities for the iwi. Auckland was officially declared New Zealand's capital in 1841[15] and the transfer of the administration from Russell (now Old Russell) in the Bay of Islands was completed in 1842. However, even in 1840 Port Nicholson (later Wellington) was seen as a better choice for an administrative capital because of its proximity to the South Island, and Wellington became the capital in 1865. After losing its status as capital Auckland remained the principal city of the Auckland Province until the provincial system was abolished in 1876.

In response to the ongoing rebellion by Hone Heke in the mid-1840s the government encouraged retired but fit British soldiers and their families to migrate to Auckland to form a defence line around the port settlement as garrison soldiers. By the time the first Fencibles arrived in 1848 the rebels in the north had been defeated so the outlying defensive towns were constructed to the south stretching in a line from the port village of Onehunga in the West to Howick in the east. Each of the four settlements had about 800 settlers, the men being fully armed in case of emergency but spent nearly all their time breaking in the land and establishing roads.

_p225_AUCKLAND%2C_NEW_ZEALAND.jpg)

In the early 1860s Auckland became a base against the Māori King Movement.[16] This, and continued road building towards the south into the Waikato, enabled Pākehā (European New Zealanders) influence to spread from Auckland. Its population grew fairly rapidly, from 1,500 in 1841 to 12,423 by 1864. The growth occurred similarly to other mercantile-dominated cities, mainly around the port and with problems of overcrowding and pollution. Auckland had a far greater population of ex soldiers, many of whom were Irish, than other settlements. About 50% of the population was Irish which contrasted heavily with the majority English settlers in Wellington, Christchurch or New Plymouth. Most of the Irish, though not all, were from Protestant Ulster. The majority of settlers in the early period were assisted by receiving a cheap passage to New Zealand.

Modern history

Trams and railway lines shaped Auckland's rapid expansion in the early first half of the 20th century, but soon afterward the dominance of the motor vehicle emerged and has not abated since; arterial roads and motorways have become both defining and geographically dividing features of the urban landscape. They also allowed further massive expansion that resulted in the growth of urban areas such as the North Shore (especially after the construction of the Auckland Harbour Bridge), and Manukau City in the south.

Economic deregulation in the mid-1980s led to dramatic changes to Auckland's economy and many companies relocated their head offices from Wellington to Auckland. The region was now the nerve centre of the national economy. Auckland also benefited from a surge in tourism, which brought 75% of New Zealand's international visitors through its airport. In 2004, Auckland's port handled 43% of the country's container trade.[17]

The face of urban Auckland changed when the government's immigration policy began allowing immigrants from Asia in 1986. According to the 1961 census data, Māori and Pacific Islanders comprised 5% of Auckland's population; Asians less than 1%.[18] By 2006 the Asian population had reached 18.0% in Auckland, and 36.2% in the central city. New arrivals from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea gave a distinctive character to the areas where they clustered, while a range of other immigrants introduced mosques, Hindu temples, halal butchers and ethnic restaurants to the suburbs. The assertiveness of Pacific Island street culture and the increasing political influence of ethnic groups contributes to the city's multicultural vitality.[17]

Geography

Harbours, gulf and rivers

Auckland lies on and around an isthmus, less than two kilometres wide at its narrowest point, between Mangere Inlet and the Tamaki River. There are two harbours in the Auckland urban area surrounding this isthmus: Waitemata Harbour to the north, which opens east to the Hauraki Gulf, and Manukau Harbour to the south, which opens west to the Tasman Sea. The total coastline of Auckland is 3,702 kilometres (2,300 mi) long.[19]

Bridges span parts of both harbours, notably the Auckland Harbour Bridge crossing the Waitemata Harbour west of the Auckland Central Business District (CBD). The Mangere Bridge and the Upper Harbour Bridge span the upper reaches of the Manukau and Waitemata Harbours, respectively. In earlier times, portage paths crossed the narrowest sections of the isthmus.

Several islands of the Hauraki Gulf are administered as part of Auckland, though they are not part of the Auckland metropolitan area. Parts of Waiheke Island effectively function as Auckland suburbs, while various smaller islands near Auckland are mostly zoned 'recreational open space' or are nature sanctuaries.

Auckland also has a total length of approximately 21,000 kilometres (13,000 mi) of rivers and streams, about 8 percent of these in urban areas.[19]

Climate

According to NIWA, Auckland has a subtropical climate, with warm, humid summers and mild, damp winters.[20] Under Köppen's climate classification, the city has an oceanic climate (Cfb).[21] It is the warmest main centre of New Zealand and is also one of the sunniest, with an average of 2,003.1 sunshine hours per annum. The average daily maximum temperature is 23.9 °C (75.0 °F) in February and 14.9 °C (58.8 °F) in July. The absolute maximum recorded temperature is 34.4 °C (93.9 °F),[22] while the absolute minimum is −3.9 °C (25.0 °F). High levels of rainfall occur almost year-round with an average of 1,115.5 mm (43.92 in) per year. Snowfall is extremely rare: the most significant fall since the start of the 20th century was on 27 July 1939, when snow stuck to the clothes of people outdoors just before dawn and five centimetres of snow reportedly lay on the summit of Mt Eden.[23] Snowflakes were also seen on 28 July 1930 and 15 August 2011.[24][25]

The early morning calm on the isthmus during settled weather, before the sea breeze rises, was described as early as 1853: "In all seasons, the beauty of the day is in the early morning. At that time, generally, a solemn stillness holds, and a perfect calm prevails...".[26] Many Aucklanders use this time of day to walk and run in parks.

Auckland occasionally suffers from air pollution due to fine particle emissions.[27] There are also occasional breaches of guideline levels of carbon monoxide.[28] While maritime winds normally disperse the pollution relatively quickly it can sometimes become visible as smog, especially on calm winter days.[29]

| Climate data for Auckland Airport (1981–2010, extremes 1962–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.5 (86.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.1 (73.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.8 (64) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.1 (61) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.8 (64) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

8.9 (48) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.9 (39) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−1.1 (30) |

−3.9 (25) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

−3.9 (25) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 73.3 (2.886) |

66.1 (2.602) |

87.3 (3.437) |

99.4 (3.913) |

112.6 (4.433) |

126.4 (4.976) |

145.1 (5.713) |

118.4 (4.661) |

105.1 (4.138) |

100.2 (3.945) |

85.8 (3.378) |

92.8 (3.654) |

1,210.7 (47.665) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.0 | 7.1 | 8.4 | 10.6 | 12.0 | 14.8 | 16.0 | 14.9 | 12.8 | 12.0 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 135.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 9am) | 79.3 | 79.8 | 80.3 | 83.0 | 85.8 | 89.8 | 88.9 | 86.2 | 81.3 | 78.5 | 77.2 | 77.6 | 82.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 228.8 | 194.9 | 189.2 | 157.3 | 139.8 | 110.3 | 128.1 | 142.9 | 148.6 | 178.1 | 188.1 | 197.2 | 2,003.1 |

| Source #1: NIWA Climate Data[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: CliFlo[31] | |||||||||||||

Volcanoes

Auckland straddles the Auckland volcanic field, which has produced about 90 volcanic eruptions from 50 volcanoes in the last 90,000 years. It is the only city in the world built on a basaltic volcanic field that is still active. It is estimated that the field will stay active for about 1 million years. Surface features include cones, lakes, lagoons, islands and depressions, and several have produced extensive lava flows. Some of the cones and flows have been partly or completely quarried away. The individual volcanoes are all considered extinct, although the volcanic field itself is merely dormant. The trend is for the latest eruptions to occur in the north west of the field. Auckland has at least 14 large lava tube caves which run from the volcanoes down towards the sea. Some are several kilometres long. A new suburb, Stonefields, has been built in an excavated lava flow, north west of Maungarei / Mount Wellington, that was previously used as a quarry by Winstones.

Auckland's volcanoes are fuelled entirely by basaltic magma, unlike the explosive subduction-driven volcanism in the central North Island, such as at Mount Ruapehu and Lake Taupo which are of tectonic origin.[32] The most recent and by far the largest volcano, Rangitoto Island, was formed within the last 1000 years, and its eruptions destroyed the Māori settlements on neighbouring Motutapu Island some 700 years ago. Rangitoto's size, its symmetry, its position guarding the entrance to Waitemata Harbour and its visibility from many parts of the Auckland region make it Auckland's most iconic natural feature. Few birds and insects inhabit the island because of the rich acidic soil and the type of flora growing out of the rocky soil.

Demographics

The Auckland metropolitan area has a population of 1,495,000 people according to Statistics New Zealand's June 2016, which is 32 percent of New Zealand's population.[2] Many ethnic groups from all corners of the world have a presence in Auckland, making it by far the country's most cosmopolitan city. Europeans make up the majority of Auckland's population, however substantial numbers of Māori, Pacific Islander and Asian peoples exist as well. Auckland has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world.[3]

The following table shows the ethnic profile of Auckland's population, as recorded in the 2001, 2006, & 2013 New Zealand Censuses.[33] The substantial percentage drop of 'Europeans' in 2006 was mainly caused by the increasing numbers of people from this group choosing to define themselves as 'New Zealanders', as a result of a media campaign that encouraged people to give the response 'New Zealander' even though this was not one of the groups listed on the census form. In the 2013 census fewer Europeans identify themselves as 'New Zealander', leading to a significant increase of numbers in 'Europeans'.[34]

| Ethnic group | 2001 census | 2006 census | 2013 census | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | (%) | Number | (%) | Number | (%) | |

| European | 755,967 | 68.5 | 700,158 | 56.5 | 789,306 | 59.3 |

| Māori | 127,704 | 11.6 | 137,304 | 11.1 | 142,770 | 10.7 |

| Pacific Island | 154,683 | 14.0 | 177,951 | 14.4 | 194,958 | 14.6 |

| Asian | 151,644 | 13.8 | 234,279 | 18.4 | 307,233 | 23.1 |

| Middle Easterners/Latin Americans/Africans | 13,335 | 1.2 | 18,558 | 1.5 | 24,945 | 1.9 |

| 'New Zealanders' | N/A | N/A | 99,474 | 8.0 | 14,904 | 1.1 |

| Others | 276 | <0.1 | 648 | 0.1 | 735 | 0.1 |

| Total responses | 1,102,818 | 1,239,054 | 1,331,427 | |||

| Not elsewhere included | 57,453 | 65,907 | 84,123 | |||

| Total population | 1,160,271 | 1,304,958 | 1,415,550 | |||

Nationalities and migration

| Largest groups of foreign-born residents[35][36] | |

| Nationality | Population (2013) |

|---|---|

| | 87,057 |

| | 70,491 |

| | 43,407 |

| | 39,087 |

| | 35,583 |

| | 30,612 |

| | 19,953 |

| | 19,470 |

| | 18,621 |

| | 18,117 |

Auckland's population is predominantly of European origin, though the proportion of those of Asian or other non-European origins has increased in recent decades due to immigration[37] and the removal of restrictions directly or indirectly based on race. Immigration to New Zealand is heavily concentrated towards Auckland (partly for job market reasons). This strong focus on Auckland has led the immigration services to award extra points towards immigration visa requirements for people intending to move to other parts of New Zealand.[38] However, this is partially offset by net emigration out of Auckland to other regions of New Zealand, mainly Waikato and Bay of Plenty.[39]

At the 2013 Census, 39.1 percent of Auckland's population were born overseas; in the local board areas of Puketapapa and Howick, overseas-born residents outnumbered those born in New Zealand.[35][36] Auckland is home to over half (51.6 percent) of New Zealand's overseas born population, including 72 percent of the country's Pacific Island-born population, 64 percent of its Asian-born population, and 56 percent of its Middle Eastern and African born population.[35]

Religion

Around 48.5 percent of Aucklanders at the 2013 census affiliated with Christianity and 11.7 percent affiliated with non-Christian religions, while 37.8 percent of the population were irreligious and 3.8 percent objected to answering. Roman Catholicism is the largest Christian denomination with 13.3 percent affiliating, followed by Anglicanism (9.1 percent) and Presbyterianism (7.4 percent).[35]

Recent immigration from Asia has added to the religious diversity of the city, increasing then number of people affiliating with Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism, although there are no figures on religious attendance.[40] There is also a small, long-established Jewish community.[41]

Lifestyle

Auckland's lifestyle is influenced by the fact that while it is 70% rural in land area, 90% of Aucklanders live in urban areas[42] – though large parts of these areas have a more suburban character than many cities in Europe and Asia.

Positive aspects of Auckland life are its mild climate, plentiful employment and educational opportunities, as well as numerous leisure facilities. Meanwhile, traffic problems, the lack of good public transport, and increasing housing costs have been cited by many Aucklanders as among the strongest negative factors of living there,[43] together with crime.[44] Nonetheless, Auckland ranked 3rd in a survey of the quality of life of 215 major cities of the world (2015 data).[45][46] In 2006, Auckland placed 23rd on the UBS list of the world's richest cities.[47]

In 2010, Auckland was ranked by the Mercer consulting firm as 149th of 214 centres on a scale of cost of living, i.e. making it among the most affordable cities worldwide to live in, with living expense of $20,000 per year, based on the comparative cost of 200 aspects of life including housing, transport, food, clothing, household goods.[48]

Leisure

One of Auckland's nicknames, the "City of Sails", is derived from the popularity of sailing in the region. 135,000 yachts and launches are registered in Auckland, and around 60,500 of the country's 149,900 registered yachtsmen are from Auckland,[49][50] with about one in three Auckland households owning a boat.[51] The Viaduct Basin, on the western edge of the CBD, hosted two America's Cup challenges (2000 Cup and 2003 Cup).

The Waitemata Harbour is home to several notable yacht clubs and marinas, including the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron and Westhaven Marina, the largest of the Southern Hemisphere.[50][52] The Waitemata Harbour has several popular swimming beaches, including Mission Bay and Kohimarama on the south side of the harbour, and Stanley Bay on the north side. On the eastern coastline of the North Shore, where the Rangitoto Channel divides the inner Hauraki Gulf islands from the mainland, there are excellent swimming beaches at Cheltenham and Narrow Neck in Devonport, Takapuna, Milford, and the various beaches further north in the area known as East Coast Bays. The west coast has popular surf spots such as Piha, Muriwai and Bethells Beach. The Whangaparaoa Peninsula, Orewa, Omaha and Pakiri, to the north of the main urban area, are also popular. Many Auckland beaches are patrolled by surf lifesaving clubs, such as Piha Surf Life Saving Club the home of Piha Rescue. All surf lifesaving clubs are part of the Surf Life Saving Northern Region.

Queen Street, Britomart, Ponsonby Road, Karangahape Road, Newmarket and Parnell are popular retail areas, whilst the Otara and Avondale fleamarkets offer an alternative shopping experience on weekend mornings. Most shopping malls are located in the middle- and outer-suburbs, with Sylvia Park and Westfield Albany being the largest.

Arts and culture

A number of arts events are held in Auckland, including the Auckland Festival, the Auckland Triennial, the New Zealand International Comedy Festival, and the New Zealand International Film Festival. The Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra is the city and region's resident full-time symphony orchestra, performing its own series of concerts and accompanying opera and ballet. Events celebrating the city's cultural diversity include the Pasifika Festival, Polyfest, and the Auckland Lantern Festival, all of which are the largest of their kind in New Zealand. Additionally, Auckland regularly hosts the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and Royal New Zealand Ballet.

Important institutions include the Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand Maritime Museum, National Museum of the Royal New Zealand Navy, and the Museum of Transport and Technology/. The Auckland Art Gallery is considered the home of the visual arts in New Zealand with a collection of over 15,000 artworks, including prominent New Zealand and Pacific Island artists, as well as international painting, sculpture and print collections ranging in date from 1376 to the present day. In 2009 the Gallery was promised a gift[53] of fifteen works of art by New York art collectors and philanthropists Julian and Josie Robertson – including well-known paintings by Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin and Piet Mondrian. This is the largest gift ever made to an art museum in Australasia.

Parks and nature

Auckland Domain is one of the largest parks in the city, close to the Auckland CBD and having a good view of the Hauraki Gulf and Rangitoto Island. Smaller parks close to the city centre are Albert Park, Myers Park, Western Park and Victoria Park.

While most volcanic cones in the Auckland volcanic field have been affected by quarrying, many of the remaining cones are now within parks, and retain a more natural character than the surrounding city. Prehistoric earthworks and historic fortifications are in several of these parks, including Maungawhau / Mount Eden, North Head and Maungakiekie / One Tree Hill.

Other parks around the city are in Western Springs, which has a large park bordering the MOTAT museum and the Auckland Zoo. The Auckland Botanic Gardens are further south, in Manurewa.

Ferries provide transport to parks and nature reserves at Devonport, Waiheke Island, Rangitoto Island and Tiritiri Matangi. The Waitakere Ranges Regional Park to the west of Auckland offers beautiful and relatively unspoiled bush territory, as do the Hunua Ranges to the south.

Sport

- Locations

Rugby union, cricket, rugby league, football and netball are widely played and followed. Auckland has a considerable number of rugby union and cricket grounds, and venues for basketball, motorsports, tennis, badminton, netball, swimming, soccer, rugby league, and many other sports.

- Eden Park is the city's primary stadium and a frequent home for international rugby union and cricket matches, in addition to Super Rugby matches where the Blues play their home games.

Eden Park stadium with statue of Rongomātāne

Eden Park stadium with statue of Rongomātāne - North Harbour Stadium is mainly used for rugby union and Football(soccer) matches, but is also used for concerts. Home Stadium for North Harbour in the ITM Cup.

- Mt Smart Stadium is used mainly for rugby league matches and is home to the New Zealand Warriors of the NRL, and is also used for concerts, previously hosting the Auckland stop of the Big Day Out music festival every January.

- ASB Tennis Centre is Auckland's primary tennis centre, hosting international tournaments for men and women (ASB Classic) in January each year. ASB Bank took over the sponsorship of the men's tournament from 2016, the event formerly being known as the Heineken Open.

- Vector Arena is an indoor arena. It is primarily used for concerts and international netball matches.

- Trusts Stadium is an indoor arena which primarily hosts netball matches, and is the home of the Northern Mystics of the ANZ Championship. It is also where the 2007 World Netball Championships were held.

- North Shore Events Centre is an indoor arena, primarily used for basketball. It is home to the New Zealand Breakers.

- Pukekohe Park Raceway is a motorsports venue that hosts V8 Supercars races annually, along with other motorsports events.

- Western Springs Stadium hosts many large-scale concerts, as well as Speedway racing during the summer, as it has done since 1929.

- Main teams

- Formerly the Auckland Blues, the Blues, a team in Super Rugby. Auckland is also home to three ITM Cup rugby teams: Auckland, North Harbour and Counties Manukau.

- Previously the Auckland Warriors, the New Zealand Warriors is a team in Australia's NRL competition. They play their home games at Mt Smart Stadium in Auckland, although some games are played at Eden Park.

- Auckland's men's first class cricket team, the Auckland Aces, play their home matches at Eden Park. The women's equivalent (the Auckland Hearts) play at Melville Park in Epsom.

- Auckland City and Waitakere United are football teams which play in the ASB Premiership.

- The Northern Mystics netball team compete in the ANZ Championship and play their home games at Trusts Stadium.

- The New Zealand Breakers is a team in the NBL and play their home matches primarily at North Shore Events Centre, although some games are played at Vector Arena.

- Major events

Annual sporting events include:

- The ASB Classic men's and women's Tennis events, held annually in January (the men's event having been named the Heineken Open prior to 2016).

- The Auckland Marathon (and half-marathon), an annual marathon which draws thousands of competitors.

- The Auckland Harbour Crossing Swim from the North Shore to the Viaduct Basin, Auckland CBD, is a yearly summer event, covering 2.8 km (often with some considerable counter-currents) and attended by over a thousand mostly amateur competitors. It is New Zealand's largest ocean swim.[54]

- The 'Round the Bays' fun-run, starting in the city and going 8.4 kilometres (5.2 mi) along the waterfront to the suburb of St Heliers. It attracts many tens of thousands of people and has been an annual March event since 1972.[55]

Auckland hosted the 1950 British Empire Games and the 14th Commonwealth Games in 1990,[14] and hosted a number of matches (including the semi-finals and the final) of the 2011 Rugby World Cup.[56] The 2012 ITU World Triathlon Series Grand Final events were held in the Auckland CBD in October 2012.[57] The 2013 Series kicks off in April in Auckland and will continue there yearly for at least 3 more years.[58]

Horse and greyhound racing

There are two thoroughbred racecourses in the city, at Ellerslie and Avondale. The former hosts the Auckland Cup and New Zealand Derby in March, and the Railway Stakes on New Year's Day, as well as many other feature events throughout the year. The famed "Ellerslie Hill" is part of what is generally recognised as one of the great steeplechase courses in world racing. The premier jumping events (the Great Northern Hurdles and Great Northern Steeplechase) are held at the beginning of September. There is also a racecourse at Pukekohe Park Raceway, inside the motor racing track.

Harness racing is held at Alexandra Park in Greenlane. The Auckland Trotting Cup is held on 31 December, with many other feature events spread throughout the year. Greyhound racing is held at Manukau Stadium.

Economy

Auckland is the major economic and financial centre of New Zealand. The city's economy is based largely on services and commerce. Most major international corporations have an Auckland office; the most expensive office space is around lower Queen Street and the Viaduct Basin in the Auckland CBD, where many financial and business services are located, which make up a large percentage of the CBD economy.[59] A large proportion of the technical and trades workforce is based in the industrial zones of South Auckland.

The largest commercial and industrial areas of the Auckland Region are in the southeast of Auckland City and the western parts of Manukau City, mostly bordering the Manukau Harbour and the Tamaki River estuary.

The sub-national GDP of the Auckland region was estimated at US$47.6 billion in 2003, 36% of New Zealand's national GDP, 15% greater than the entire South Island.[60]

Auckland's status as the largest commercial centre of the country reflects in the high median personal income (per working person, per year) which was NZ$44,304 (approx. US$33,000) for the region in 2005, with jobs in the Auckland CBD often earning more.[61] The median personal income (for all persons older than 15 years of age, per year) in Auckland was NZ$41,860 (2014) behind only Wellington.[62]

Education

Primary and secondary

The Auckland urban area has 340 primary schools, 80 secondary schools, and 29 composite (primary/secondary combined) schools as of February 2012, catering for nearly quarter of a million students. The majority are state schools, but 63 schools are state-integrated and 39 are private.[64]

The city is home to some of the largest schools in New Zealand, including Rangitoto College in the East Coast Bays area, the largest school in New Zealand with 3110 students as of July 2016.[65]

Tertiary

Auckland has a number of important educational institutions, including some of the largest universities in the country. Auckland is a major centre of overseas language education, with large numbers of foreign students (particularly East Asians) coming to the city for several months or years to learn English or study at universities – although numbers New Zealand-wide have dropped substantially since peaking in 2003.[66] As of 2007, there are around 50 New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) certified schools and institutes teaching English in the Auckland area.[67]

Amongst the more important tertiary educational institutes are the University of Auckland, Auckland University of Technology, Massey University, Manukau Institute of Technology and Unitec New Zealand.

Housing

Housing varies considerably between some suburbs having state owned housing in the lower income neighbourhoods, to palatial waterfront estates, especially in areas close to the Waitemata Harbour. Traditionally, the most common residence of Aucklanders was a standalone dwelling on a 'quarter acre' (1,000 m²).[68] However, subdividing such properties with 'infill housing' has long been the norm. Auckland's housing stock has become more diverse in recent decades, with many more apartments being built since the 1970s – particularly since the 1990s in the CBD.[69] Nevertheless, the majority of Aucklanders live in single dwelling housing and are expected to continue to do so – even with most of future urban growth being through intensification.[68]

Auckland's housing is amongst the least affordable in the world, based on comparing average house prices with average household income levels[70] and house prices have grown well above the rate of inflation in recent decades.[69] In August 2016, Quotable Value reported the average house price for Auckland metro was $1,014,000, compared with $536,000 in Wellington metro, $518,000 in Hamilton, $493,000 in Christchurch, and $144,500 in the Ruapehu District (the area with the lowest average house price in New Zealand).[71] There is significant public debate around why Auckland's housing is so expensive, often referring to a lack of land supply,[69] the easy availability of credit for residential investment[72] and Auckland's high level of liveability.

In some areas, the Victorian villas have been torn down to make way for redevelopment. The demolition of the older houses is being combated through increased heritage protection for older parts of the city.[73] Auckland has been described as having 'the most extensive range of timbered housing with its classical details and mouldings in the world', many of them Victorian-Edwardian style houses.[74]

Housing crisis

In the late 2000s, a housing crisis began in Auckland with the market not being able to sustain the demand for affordable homes. The Housing Accords and Special Housing Areas Act 2013 mandated that a minimum of 10% of new builds in certain housing areas be subsidized to make them affordable for buyers who had incomes on par with the national average. In a new subdivision at Hobsonville Point, 20% of new homes were reduced to below $550,000.[75] Some of the demand for new housing is attributed to the 43,000 people who moved into Auckland between June 2014 and June 2015.[76]

Government

Local

The Auckland Council is the local council with jurisdiction over the city of Auckland, along with surrounding rural areas, parkland, and the islands of the Hauraki Gulf.

From 1989 to 2010 Auckland was governed by several separate city and district councils. In the late 2000s (decade), New Zealand's central government and parts of Auckland's society felt that this large number of councils, and the lack of strong regional government (with the Auckland Regional Council having only limited powers) were hindering Auckland's progress. A Royal Commission on Auckland Governance was set up in 2007,[77][78] and in 2009 recommended a unified local governance structure for Auckland, amalgamating the councils.[79] Government subsequently announced that a "super city" would be set up with a single mayor by the time of New Zealand's local body elections in 2010.[80][81] Many aspects of the reorganisation were or are still controversial, from matters such as the form of representation for Maori, the inclusion or exclusion of rural council areas in the city, to the role of council-controlled organisations that are intended to place much of the day-to-day business of council services at arms length from the elected Council.

In October 2010, Manukau City mayor Len Brown was elected mayor of the amalgamated Auckland Council. He was re-elected for a second term in October 2013. Brown did not stand for re-election in the 2016 mayoral election, and was succeeded by successful candidate Phil Goff in October 2016.[82] Twenty councillors make up the remainder of the Auckland Council governing body, elected from thirteen electoral wards.

National

Between 1842 and 1865, Auckland was the capital city of New Zealand. Parliament met in what is now Old Government House on the University of Auckland's City campus. The capital was moved to the more centrally located Wellington in 1865.

Auckland, because of its large population, is covered by 22 general electorates and three Maori electorates,[83] each returning one member to the New Zealand House of Representatives. The governing National Party holds thirteen general electorates, the opposing Labour Party holds eight general electorates and all three Maori electorates, and ACT holds the remaining electorate (Epsom).

In addition, there are a varying number of Auckland-based List MPs, who are elected via party lists. As of December 2015, there are twelve list MPs in the House who contested Auckland-based electorates at the 2014 election: six from National, four from Green, and one each from Labour and New Zealand First.

Other

The administrative offices of the Government of the Pitcairn Islands is situated in Auckland.[84]

Transport

Travel modes

- Road and rail

Private vehicles are the main form of transportation within Auckland, with around 7% of journeys in the Auckland region undertaken by bus in 2006,[85] and 2% undertaken by train and ferry.[85] For trips to the city centre at peak times the use of public transport is much higher, with more than half of trips undertaken by bus, train or ferry.[86] Auckland still ranks quite low in its use of public transport, having only 46 public transport trips per capita per year,[86][87] while Wellington has almost twice this number at 91, and Sydney has 114 trips.[88] This strong roading focus results in substantial traffic congestion during peak times.[89]

Bus services in Auckland are mostly radial, with few cross-town routes. Late-night services (i.e. past midnight) are limited, even on weekends. A major overhaul of Auckland's bus services is being implemented during 2016–17, significantly expanding the reach of "frequent" bus services: those that operate at least every 15 minutes during the day and early evening, every day of the week.[90]

Rail services operate along four lines between the CBD and the west, south and south-east of Auckland, with longer-distance trains operating to Wellington only a few times each week.[91] Following the opening of Britomart Transport Centre in 2003, major investment in Auckland's rail network occurred, involving station upgrades, rolling stock refurbishment and infrastructure improvements.[92][93] The rail upgrade has included electrification of Auckland's rail network, with electric trains constructed by Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles commencing service in April 2014.[94] A number of proposed projects to further extend Auckland's rail network were included in the 2012 Auckland Plan, including the City Rail Link, rail to Auckland Airport, the Avondale-Southdown Line and rail to the North Shore.

- Other modes

Auckland's ports are the second largest of the country, behind the Port of Tauranga,[95] and a large part of both inbound and outbound New Zealand commerce travels through them, mostly via the facilities northeast of Auckland CBD. Freight usually arrives at or is distributed from the port via road, though the port facilities also have rail access. Auckland is a major cruise ship stopover point, with the ships usually tying up at Princes Wharf. Auckland CBD is connected to coastal suburbs, to the North Shore and to outlying islands by ferry.

- Air

Auckland has various small regional airports and Auckland Airport, the busiest of the country. Auckland Airport, New Zealand's largest, is in the southern suburb of Mangere on the shores of the Manukau Harbour. There are frequent services to Australia, and to other New Zealand destinations. There are also direct connections to many locations in the South Pacific, as well as the United States, Asia and Santiago and Buenos Aires in South America.[96]

- Policies

Research at Griffith University has indicated that in the last 50 years, Auckland has engaged in some of the most pro-automobile transport policies anywhere in the world.[97] With public transport declining heavily during the second half of the 20th century (a trend mirrored in most Western countries such as the US),[98] and increased spending on roads and cars, New Zealand (and specifically Auckland) now has the second-highest vehicle ownership rate in the world, with around 578 vehicles per 1000 people.[99] Auckland has also been called a very pedestrian- and cyclist-unfriendly city, though some efforts are being made to change this.[100] At the same, high-profile gaps in the network, such as the inability for pedestrians and cyclists to cross the Waitemata Harbour, will probably remain for the foreseeable future, with councils generally not considering the costs involved as sensible expense.[101]

Infrastructure

The State Highway network connects the different parts of Auckland, with State Highway 1 being the major north-south thoroughfare through the city (including both the Northern and Southern Motorways) and the main connection to the adjoining regions of Northland and Waikato. The Northern Busway runs alongside part of the Northern Motorway on the North Shore. Other state highways within Auckland include State Highway 16 (the Northwest Motorway), State Highway 18 (the Upper Harbour Motorway) and State Highway 20 (the Southwest Motorway). State Highway 22 is a non-motorway rural arterial connecting Pukekohe to the Southern Motorway at Drury.

The Auckland Harbour Bridge, opened in 1959, is the main connection between the North Shore and the rest of the Auckland metropolitan area. The bridge provides eight lanes of vehicle traffic and has a moveable median barrier for lane flexibility, but does not provide access for rail, pedestrians or cyclists. The Central Motorway Junction, also called 'Spaghetti Junction' for its complexity, is the intersection between the two major motorways of Auckland (State Highway 1 and State Highway 16).

Two of the longest arterial roads within the Auckland Region are Great North Road and Great South Road – the main connections in those directions before the construction of the State Highway network. Numerous arterial roads also provide regional and sub-regional connectivity, with many of these roads (especially on the isthmus) previously used to operate Auckland's former tram network.

Auckland has four railway lines (Western, Onehunga, Eastern and Southern). These lines serve the western, southern and eastern parts of Auckland from the Britomart Transport Centre in downtown Auckland, the terminal station for all lines, where connections are also available to ferry and bus services. Work began in late 2015 to provide more route flexibility and connect Britomart more directly to western suburbs on the Western Line via an underground rail tunnel known as the City Rail Link project.

Electricity

Auckland is New Zealand's largest electricity consumer, and uses around 20% of the country's total electricity each year. Vector, which operates the majority of Auckland's local distribution system, measured maximum demand to be 1722 MW in 2011, with 8679 GWh delivered.[102]

There are no electricity generation stations located within the city. There were two natural gas-fired power stations (the 380 MW Otahuhu B owned by Contact Energy and the 175 Southdown owned by Mighty River Power) have been shut down. Since there is very little generation north of Auckland, almost all of the electricity for Auckland and Northland must be transmitted from power stations in the south, mainly from Huntly Power Station and the Waikato River hydroelectric stations.

Transpower owns the national grid and is responsible for the high voltage transmission lines into and across Auckland. Five major 220 kV transmission lines connect Auckland with the Waikato, terminating into Otahuhu and Brownhill substations. The sub-transmission and distribution network in the Auckland region is mostly owned by Vector. The network south of central Papakura is owned by Counties Power.

There have been several notable power outages in Auckland. The five-week-long 1998 Auckland power crisis blacked out much of the CBD after a cascade failure occurred on four underground cables in Mercury Energy's sub-transmission network. The 2006 Auckland Blackout interrupted supply to the CBD and many inner suburbs after an earth wire shackle at Transpower's Otahuhu substation broke and short-circuited the lines supplying the inner city. In 2009, much of the northern and western suburbs, as well as all of Northland, experienced a blackout when a forklift accidentally came into contact with the Otahuhu to Henderson 220 kV line, the only major line supplying the region.[103] Transpower spent $1.25 billion in the early 2010s reinforcing the supply into and across Auckland, including a 400 kV-capable transmission line from the Waikato River to Brownhill substation (operated at 220 kV initially), and 220 kV underground cables between Brownhill and Pakuranga, and between Pakuranga and Albany via the CBD. These reduced the Auckland Region's reliance on Otahuhu substation and northern and western Auckland's reliance on the Otahuhu to Henderson line.

Future growth

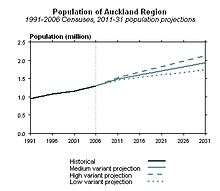

Auckland is experiencing substantial population growth via natural population increases (one-third of growth) and immigration (two-thirds),[104] and is set to grow to an estimated 1.9 million inhabitants by 2031[68][105] in a medium-variant scenario. This substantial increase in population will have a major impact on transport, housing and other infrastructure that are, particularly in the case of housing, already considered under pressure. The high-variant scenario shows the region's population growing to over two million by 2031.[106]

In July 2016, Auckland Council released, as the outcome of a three-year study and public hearings, its Unitary Plan for Auckland. The plan aims to free up to 30 per cent more land for housing and allows for greater intensification of the existing urban area, creating 422,000 new dwellings in the next 30 years.[107]

Famous sights

Tourist attractions and landmarks in the Auckland metropolitan area include:

- Attractions and buildings

- Auckland Civic Theatre – an internationally significant heritage atmospheric theatre built in 1929. It was renovated in 2000 to its original condition.

- Auckland Harbour Bridge – connecting Central Auckland and the North Shore, an iconic symbol of Auckland.

- Auckland Town Hall – with its concert hall considered to have some of the finest acoustics in the world, this 1911 building serves both council and entertainment functions.

- Auckland War Memorial Museum – a large multi-exhibition museum in the Auckland Domain, known for its impressive neo-classicist style, built in 1929.

- Aotea Square – the hub of downtown Auckland beside Queen Street, it is the site of rallies and arts festivals.

- Aotea Centre – Auckland Civic Centre building completed in 1989.

- St Patrick's Cathedral – the Catholic Cathedral of Auckland. A 19th century Gothic building which was renovated from 2003 to 2007 for refurbishment and structural support.

- Britomart Transport Centre – the main downtown public transport centre in a historic Edwardian building.

- Eden Park – the city's primary stadium and a frequent home for All Blacks rugby union and Black Caps cricket matches. It was the location of the 2011 Rugby World Cup final.[108]

- Karangahape Road – known as "K' Road", a street in upper central Auckland famous for its bars, clubs, smaller shops and being a former red-light district.

- Kelly Tarlton's Sea Life Aquarium – an aquarium and Antarctic environment in the eastern suburb of Mission Bay, built in a set of former sewage storage tanks, showcasing penguins, turtles, sharks, tropical fish, sting rays and other marine creatures.

- MOTAT – the Museum of Transport and Technology, at Western Springs.

- Mt Smart Stadium – a stadium used mainly for rugby league and soccer matches, and also concerts.

- New Zealand Maritime Museum – features exhibitions and collections relating to New Zealand maritime history at Hobson Wharf, adjacent to Viaduct Basin.

- Ponsonby – a suburb and main street immediately west of central Auckland, known for arts, cafes, culture and historic villas.

- Queen Street – the main street of the city, running from Karangahape Road down to the harbour.

- Sky Tower – the tallest free-standing structure in the Southern Hemisphere, it is 328 m (1,076 ft) tall and has excellent panoramic views.

- Vector Arena – events centre in downtown Auckland completed in 2007. Holding 12,000 people, it is used for sports and concert events.

- Viaduct Basin – a marina and residential development in downtown Auckland, and the venue for the America's Cup regattas in 2000 and 2003.

- Western Springs Stadium – a natural amphitheatre used mainly for speedway races, rock and pop concerts.

- Landmarks

- Auckland Domain – one of the largest parks of the city, close to the CBD and having a good view of the harbour and of Rangitoto Island.

- Maungawhau / Mount Eden – a volcanic cone with a grassy crater. The highest natural point in Auckland City, it offers 360-degree views of Auckland and is thus a favourite tourist outlook.

- Takarunga / Mount Victoria – a volcanic cone on the North Shore offering a spectacular view of downtown Auckland. A brisk walk from the Devonport ferry terminal, the cone is steeped in history, as is nearby Maungauika (North Head).

- Maungakiekie / One Tree Hill – a volcanic cone that dominates the skyline in the southern inner suburbs. It no longer has a tree on the summit (after a politically motivated attack on the erstwhile tree,) but is crowned by an obelisk.

- Rangitoto Island – guards the entrance to Waitemata Harbour, and forms a prominent feature on the eastern horizon.

- Waiheke Island – the second largest island in the Hauraki Gulf and known for its beaches, forests, vineyards and olive groves.

Sister cities

Auckland Council maintains relationships with the following cities[109]

|

With the exceptions of Hamburg and Galway, all of these cities are located within the Pacific Rim.

See also

- East Auckland

- Jafa (slang term for Aucklander, article also contains a range of Aucklander stereotypes)

- List of tallest buildings in Auckland

References

- ↑ Monitoring Research Quarterly, March 2011 Volume 4 Issue 1, page 4.

- 1 2 3 4 "Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2016 (provisional)". Statistics New Zealand. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016. For urban areas, "Subnational population estimates (UA, AU), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996, 2001, 2006-16 (2017 boundary)". Statistics New Zealand. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Auckland and around". Rough Guide to New Zealand, Fifth Edition. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ↑ McClure, Margaret (5 August 2016). "Auckland region – Māori history". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 Ferdinand von Hochstetter (1867). New Zealand. p. 243.

- ↑ "Quality of living rankings spotlight emerging cities". Mercer. June 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "Global Liveability Ranking 2016". The Economist Intelligence Unit. August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2010t.html | "The World According to GaWC 2008"

- ↑ Long-Range Futures Research: An Application of Complexity Science, Robert Samet, 2009, 272

- ↑ Sarah Bulmer. "City without a state? Urbanisation in pre-European Taamaki-makau-rau (Auckland, New Zealand)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ "Ngāti Whātua – European contact". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Auckland, N.Z.: Penguin Books. p. 135. ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- ↑ George Weller's Claim to lands in the Hauraki Gulf – transcript of original in National Archives, ms-0439/03 (A-H) HC.

- 1 2 What's Doing In; Auckland – The New York Times, 25 November 1990

- ↑ Russell Stone (2002). From Tamaki-Makau-Rau to Auckland. University of Auckland Press. ISBN 1-86940-259-6.

- ↑ http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/politics/treaty/the-treaty-in-practice/slide-to-war

- 1 2 "Auckland Region – Driving the Economy: 1980s Onwards". Te Ara, Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ "Auckland Now". Royal Commission on Auckland Governance.

- 1 2 Auckland Council (2012). Draft Long-term Plan 2012–2022. p. 13.

- ↑ "Overview of New Zealand Climate—Northern New Zealand". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11: 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ↑ "Climate Summary Table". MetService. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ Brenstrum, Erick (June 2003). "Snowstorms" (PDF). Tephra. Ministry of Civil Defence. 20: 40–52. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ↑ Brenstrum, Erick (November 2011). "Snowed in". New Zealand Geographic. Kowhai Publishing (112): 26–27.

- ↑ Wade, Amelia (15 August 2011). "Snow falls in Auckland for first time in decades". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ↑ Auckland, the Capital of New Zealand – Swainson, William, Smith Elder, 1853

- ↑ "Air pollutants – Fine particles (PM10 and PM2.5)". Auckland Regional Council. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Air pollutants – Carbon monoxide (CO)". Auckland Regional Council. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Auckland's air quality". Auckland Regional Council. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Auckland 1981–2010 averages". NIWA. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ "CliFLO – National Climate Database". NIWA. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ Ian E.M. Smith and Sharon R. Allen. Auckland volcanic field geology. Volcanic Hazards Working Group, Civil Defence Scientific Advisory Committee. Retrieved 30 March 2013. Also published in print as Volcanic hazards at the Auckland volcanic field. 1993.

- ↑ 2013 Census about a place: Auckland region, Cultural Diversity

- ↑ 2013 Census QuickStats about national highlights

- 1 2 3 4 "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity – data tables". Statistics New Zealand. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Birthplace (detailed), for the census usually resident population count, 2001, 2006, and 2013 (RC, TA) – NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "New Zealand – A Regional Profile – Auckland" (PDF). Statistics New Zealand. 1999. pp. 19–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ Residence in New Zealand (PDF) (Page 8, from the Immigration New Zealand website. Accessed 18 January 2008.)

- ↑ "New Zealand's population is drifting north – Population mythbusters". Statistics New Zealand. 22 June 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "What we look like locally" (PDF). Statistics New Zealand. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2007.

- ↑ "Auckland Hebrew Community ~ Introduction page". Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ↑ "Auckland Council – History in the Making". Our Auckland. Auckland Council. March 2011. p. 5.

- ↑ Central Transit Corridor Project (Auckland City website, includes mention of effects of transport on public satisfaction)

- ↑ "Crime and safety profile – 2003". Auckland City Council. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ↑ "City Mayors: Best cities in the world". citymayors.com.

- ↑ Quality of Living global city rankings 2009 (Mercer Management Consulting. Retrieved 2 May 2009).

- ↑ City Mayors: World's richest cities (UBS via www.citymajors.com website, August 2006)

- ↑ Nordqvist, Susie (29 June 2010). "Auckland, Wellington, among 'best value' cities in the world". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ Punters love City of Sails – The New Zealand Herald, Saturday 14 October 2006

- 1 2 Passion for boating runs deep in Auckland – The New Zealand Herald, Thursday 26 January 2006

- ↑ "The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, Part 2". Inset to The New Zealand Herald. 2 March 2010. p. 4.

- ↑ [Sailing Club] directory (from the yachtingnz.org website)

- ↑ "Julian and Josie Robertson Collection". Auckland Art Gallery. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Harbour Crossing (from the Auckland City Council website. Retrieved 24 October 2007.)

- ↑ "Ports of Auckland Round the Bays (Official)". Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ "Eden Park to host Final and semi-finals". 22 February 2008.

- ↑ "ITU World Championship Series Grand Final". Triathlon New Zealand. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ "ITU World Series back to Auckland 6–7 April 2013". World Triathlon Auckland. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ Auckland's CBD at a glance (CBD website of the Auckland City Council)

- ↑ "Regional Gross Domestic Product". Statistics New Zealand. 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ Auckland Regional Profile (from labourmarket.co.nz, composed from various sources)

- ↑ Comparison of New Zealand's cities (from ENZ emigration consulting)

- ↑ Heritage Sites to Visit: Auckland City. New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ↑ "Directory of Schools – as at 01 February 2012". Ministry of Education New Zealand. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Directory of Schools - as at 2 August 2016". New Zealand Ministry of Education. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- ↑ Survey of English Language Providers – Year ended March 2006 (from Statistics New Zealand. Auckland is assumed to follow national pattern)

- ↑ English Language Schools in New Zealand – Auckland (list linked from the Immigration New Zealand website)

- 1 2 3 Executive Summary (PDF) (from the Auckland Regional Growth Strategy document, ARC, November 1999. Retrieved 14 October 2007.)

- 1 2 3 "Residential Land Supply Reports". Department of Building and Housing. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" (PDF). Demographia. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Residential house values". Quotable Value. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Brockett, Matthew. "Auckland's New York House Prices Prompt Lending Curbs: Mortgages". Bloomberg. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Unitary Plan Key Topics: Historic Heritage and Special Character" (PDF). Auckland Council. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Section 7.6.1.2 – Strategy (PDF) (from the Auckland City Council District Plan – Isthmus Section)

- ↑ "Special Housing Areas". www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ "Auckland's growing population". OurAuckland. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ Auckland governance inquiry welcomed – NZPA, via 'stuff.co.nz', Tuesday 31 July 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ↑ Royal Commission of inquiry for Auckland welcomed – NZPA, via 'infonews.co.nz', Tuesday 31 July 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007

- ↑ Minister Releases Report Of Royal Commission – Scoop.co.nz, Friday 27 March 2009

- ↑ Gay, Edward (7 April 2009). "'Super city' to be in place next year, Maori seats axed". The New Zealand Herald.

- ↑ "Making Auckland Greater" (PDF). The New Zealand Herald. 7 April 2009.

- ↑ "Phil Goff elected Mayor of Auckland". 8 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ "Find my electorate". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ↑ "Home." Government of the Pitcairn Islands. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- 1 2 Auckland Transport Plan – June 2007 (PDF). Auckland Regional Transport Authority. 2007. p. 8.

- 1 2

- ↑ "Subnational population estimates tables". Stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Auckland's Transport Challenges (from the Draft 2009/10-2011/12 Auckland Regional Land Transport Programme, Page 8, ARTA, March 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ↑ Welcome to our traffic nightmare – The New Zealand Herald, Sunday 29 July 2007

- ↑ "New Network Project". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "Scenic Journeys – Northern Explorer". KiwiRail. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ References provided in Transport in Auckland and Public transport in Auckland

- ↑ Auckland Transport Plan landmark for transport sector (from the Auckland Regional Transport Authority website, 11 August 2007)

- ↑ "Electric Trains". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ "http://www.taurikobusinessestate.co.nz/about_tauranga.php"

- ↑ Auckland Airport, http://www.aucklandairport.co.nz/

- ↑ 2006.pdf Backtracking Auckland: Bureaucratic rationality and public preferences in transport planning – Mees, Paul; Dodson, Jago; Urban Research Program Issues Paper 5, Griffith University, April 2006

- ↑ US Urban Personal Vehicle & Public Transport Market Share from 1900 (from publicpurpose.com, a website of the Wendell Cox Consultancy)

- ↑ Sustainable Transport North Shore City Council website

- ↑ Big steps to change City of Cars – The New Zealand Herald, Friday 24 October 2008

- ↑ Cycleway for bridge could prove too pricey – The New Zealand Herald, Wednesday 3 September 2008

- ↑ "Electricity Asset Management Plan 2012 – 2022" (PDF). Vector Limited. April 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ "Forklift sparks blackout for thousands – tvnz.co.nz". Television New Zealand. 30 October 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ↑ "Auckland's growing population". OurAuckland. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Mapping Trends in the Auckland Region Statistics New Zealand, 2010. Retrieved 2010)

- ↑ "Mapping Trends in the Auckland Region". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Auckland's future unveiled". New Zealand Herald. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ "Venue allocation options a challenge". Official RWC 2011 Site. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Auckland Council's sister-city agreements". Auckland Council. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "Sister Cities of Guangzhou". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Auckland. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Auckland. |

- Auckland – Visitor-oriented official website

- Auckland travel guide – NewZealand.com (New Zealand's official visitor guide and information)

- Auckland in Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Maps & aerial photos (from the ARC map website)